Читать книгу Not Child's Play - Dave Muller - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Prologue

ОглавлениеTo die will be an awfully big adventure.

– JM Barrie, Peter Pan

The date is 28 April 2013 and I am in Burundi as an architect, part of a volunteer group of building professionals assisting with the replanning of a run-down mission hospital, a victim of the wave of hatred that poured over Burundi and neighbouring Rwanda in 1994. The hospital is itself a trauma case. Our efforts are a first step towards resuscitation and the dream of it becoming the academic teaching hospital for the optimistically named Hope Africa University, based 60 kilometres north in the capital, Bujumbura.

The founders of Kibuye Hospital chose their site well. We are high, 1 750 metres above sea level, the most southerly source of the Nile dribbling from a rocky seep just a few kilometres away. So even though we are almost on the equator, the climate is crisp, and as the evening gloom drenches the softly creased highlands, a reviving coolness washes over the countryside and spills into the valleys. Our team sits around an archipelago of hastily assembled tables, focused on our evening meal. Outside, the resident scops owl chirrs warnings into the grey twilight from the tall eucalyptus trees, anticipating its own dinner.

We’ve been together for four days and, as is the daily routine, Phil asks one of the team to explain what motivated them to volunteer. This night, of all nights, the lot has fallen on me. I can short-circuit my story and leave out the detail, but the sight of throngs of expended women, hollow-chested old men and sad-eyed children has scraped away the scar tissue protecting my memories. This place has exposed them, and the date – even the hour – seems portentous, and so my memories bleed.

Exactly 23 years ago I was blundering through darkness, trying to keep up with the boys ahead, guided more by sound than sight as we crash and stagger through the coastal dune forest. Sandy and Tammy stumble behind me. Another boy prods us forward with his AK-47. Seth clings to my sweat-sodden back.

I have an overwhelming need to tell the story. To dilute the horror in exculpation. I’m back there. Vivid memories – sights, sounds, tastes and smells – still lurk. How do I explain this overwhelming sense of being tainted, contaminated, maybe even infected by something horrible and repressed; something to which we all too glibly assign the word ‘evil’? How do I explain this irrational feeling I’m carrying, buried deep inside me, the pain of knowing first-hand the trauma of Mozambique’s past.

I’ve sensed that same burden here in Burundi, a country that has faced two genocides. Everyone we’ve met is gentle and moving along with the slow diurnal pace of their lives. But always, always, there is a hesitation, a void left in conversation. Don’t ask about the past. Some things cannot be explained, so don’t go there. Rather press forward, trusting that maybe, just maybe, cleansing and a step toward redemption can be found in acts of kindness. Maybe that is why I am here. To reclaim an innocence through acts of giving and service. To trust that I can find healing in self-sacrifice. And so I brandish this sign of hope like a crisp washed-white garment that at this moment is focused on the resurgence of Kibuye Hospital.

I launch into my story and, in the camaraderie of new friendships, I feel comfortable telling it. That is until I reach the point two hours after sunset on 28 April 1990, 23 years ago to the hour, when we – me, Sandy, my wife, and our two children, eight-year-old Tammy and five-year-old Seth – found ourselves seated in a shallow clearing, the soft, downy star-glow above defining a wall of dark vegetation around us. The elderly couple, our fellow captives, are not with us, the implication missed. We’re exhausted, soaked in sweat, terrified, and profoundly lost when those sounds come from the darkness. Once again I hear them clearly in my head. Slushy, sucking, stabbing wet sounds just metres away.

Too late I realise I should not have ventured there with my story. I should have skirted this moment that has so viscerally exposed humanity’s brutality. This has happened before and the memories, the burden, flood me. My voice is lost amid the sobs.

My listeners, of course, don’t know how to react. I am back in Mozambique, but I hear them like a distant shadow of sound. There is concern in their voices. ‘Are you all right? What’s wrong?’ All I can choke out are words formed elsewhere, far away, in a distant time. I have no control over them, they just come, and come, and come, without bidding.

‘They were just children.’ All I can say again and again as I struggle for breath is, ‘You don’t understand … they were just children.’

Afterwards, there are many apologies, but it is not their fault. I went where I knew danger lurked, unlocking strong rooms of the mind best kept shut. Surely, after all these years, those memories would by now be softened, even erased. A few days later someone kindly suggests I visit a psychologist once I get home to South Africa. They are probably right, but I decide it is time for purging. Time to tell this story.

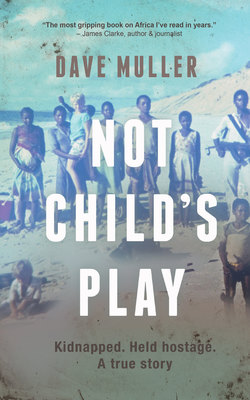

So, once back home, I find the cardboard box containing the relics from that time. A collection of photographs and newspaper clippings. Old exercise books filled with children’s writing and drawings. A postcard of a man in a military uniform. A fifty-rand banknote. A few spent bullets and empty cartridges. The beautiful woven basket given as a gift. The carved wooden dice, spoons and the cleft sticks used for drying fish. The palm-frond tweezers for extracting bullets. And at the bottom of the box, most precious of all, the diary I kept.