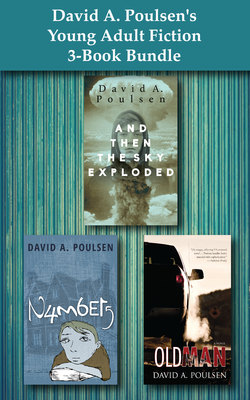

Читать книгу David A. Poulsen's Young Adult Fiction 3-Book Bundle - David A. Poulsen - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The A Shau Valley

Оглавление1

I woke up and freaked.

In the pre-dawn semi-light, I was sure of one thing — I’d been carried off to a giant jungle spider’s web. The spider’s webbing was all around me. I tried to move my eyes without moving my head so that whatever it was that had taken me prisoner wouldn’t know I was still alive. Or awake.

I didn’t see a spider. But I did hear the old man’s voice outside the tent, talking softly, and Mr. Vinh’s high-pitched singsong answering.

“Uh … morning,” I called out. I didn’t want to let on that I might need to be rescued from a bloodthirsty insect, but I wouldn’t have minded if the old man happened to look into the tent right about then.

He didn’t. “Hey, Nathan, gather up that mosquito netting as you’re getting up. We’ll need it again tonight.”

I pulled my hand out from under the covers and gently reached up, touched the spider’s web. Mosquito netting.

“Uh, yeah, mosquito netting. I’ll gather up the mosquito netting. I’ll just gather it up. No problem.”

“Good.” I heard the old man saying something to Mr. Vinh. I was pretty sure the phrase “strange kid” was part of what he said.

I gave up on the netting long enough to pull on the rest of my clothes. It didn’t take long since I hadn’t totally undressed the night before. I’d pulled off my shirt and running shoes and that was it. I had this feeling that sleeping in your gonch in the jungle was an open invitation for some creature to sneak into your sleeping bag and start gnawing on some private area best left un-gnawed.

I’d just finished getting the shirt and shoes back on and picked up the jumble of netting when the old man and Mr. Vinh stomped into the tent, wearing slickers but looking wet anyway. Raining outside. The old man was carrying the briefcase. He opened it and pulled out what looked like some maps … and a couple of old photographs.

They both sat on the floor of the tent. The old man was sitting cross-legged with the briefcase in his lap, lid down, and one of the maps lying on its surface. Mr. Vinh sat next to him. Both were staring hard at the map.

The old man pointed at a couple of points on the map. Mr. Vinh nodded and spoke in a mix of Vietnamese and English that was pretty well gibberish to me. The old man answered him also with a mix of words, most of them one syllable. As usual, I understood pretty well nothing.

But it was quite an animated conversation. A couple of times Mr. Vinh didn’t seem to know the answer to whatever the old man wanted to know. When that happened, he shrugged and shook his head. The old man’s voice got pretty loud right about then. After maybe the third time it happened, the old man looked up at me. It was like he suddenly realized I was there, still sorting mosquito netting and watching the two of them.

“Get that sleeping bag rolled up and into that duffel bag outside, the bigger one. The mosquito netting too.” That was it. He went back to the map, except that now he had some of the photographs spread out on the briefcase, and he was pointing at them too.

I gathered up the netting and sleeping bag and stepped out of the tent. The rain wasn’t hard, but there was enough of it that I knew I’d be soaked pretty fast. There was a gathering of branches next to the tent, sort of a lean-to and the two duffel bags were under it. I didn’t remember the lean-to from the night before. Maybe they’d put it up after I’d gone to bed or maybe it was there from before. I didn’t know and it didn’t matter. What mattered was that it was dry under there. I took my time packing up the rest of the gear.

The old man and Mr. Vinh came out of the tent, and the old man tossed a slicker to me. I pulled it over my head, lifted the hood into position and stepped out from under the lean-to. It was raining harder now, a lot harder. Even with the slicker I got pretty wet … pretty fast. Not as bad as after the swamp episode but fairly damp just the same.

I went around to the other side of the lean-to to take a leak. It was the most privacy I could hope for unless I wanted to go out into the jungle a ways. And I didn’t want to do that.

We ate bananas, two each, under the lean-to before heading out. Nobody was going to get fat on this trip. That was obvious. I pulled my hood back just long enough to check the sky. It looked like the clouds were about fifty metres above our heads and the rain was coming down even harder. Nice day for a walk in the jungle.

I gathered the canteens and the backpack. The old man had stashed the briefcase in the bigger duffel bag, so I didn’t have to carry it anymore. Mr. Vinh grunted a couple of times and started off across the clearing, machete in hand, toward the jungle that was on the other side. This time the old man nodded that he wanted me to go next and that he’d be at the back. I didn’t mind that actually. At least this way I wouldn’t get lost in the jungle or picked off by some python without anyone even knowing.

2

I don’t know how long we walked. I do know that the rain stopped. Trouble was, it was actually worse after that. Hot with a humidity of maybe four hundred percent. Steam was actually rising off the jungle floor. I pulled off the slicker, but it didn’t matter. I think I was wetter when it wasn’t raining than when it was. I laid on my second layer of mosquito repellant. I noticed something unpleasant. The mix of sweat and mosquito juice and the lack of shower facilities (I didn’t count my dip in the swamp) didn’t make for a really great-smelling boy. I was pretty sure neither of the Jens would have found me all that attractive right about then.

We finally came out of the jungle, and there was this field stretched across in front of us. Neat rows of plants stood maybe a foot high in a layer of water across the whole field. The water looked to be about fifteen centimetres deep. Maybe more. The old man came up alongside me.

“Rice paddy,” he said. “There was one in about this area the last time I made this walk. May be the same one.”

I was thinking who cares.

Then he pointed. There was another stretch of jungle on the other side of the rice paddy, not very big this time, and a hill that kind of rose up out of it. Behind that hill there were a couple of good-sized looking mountains.

“That’s where we’re going. Hill 453. Not a very exotic name is it? Not like Hamburger Hill, the one they made the movie about — that’s over there.” He waved an arm in an arc to his right, but there were lots of hills and mountains in that direction, so I didn’t know which one he meant. I’d seen the movie but I couldn’t remember very much about it, other than the name.

I looked at the hill we were heading for. Not a real big deal. Hill 453 definitely didn’t look like it was worth fighting for. Or dying for. I wondered if people had died on that hill during whatever happened when the old man was there. And I wondered if I’d find out.

“Stay as close to him as you can,” the old man told me, nodding toward Mr. Vinh. “And don’t decide to stroll off the path any.”

“What path?” I wasn’t trying to be funny. If there was a path, I was having a tough time seeing it. Yet there had to be one since Mr. Vinh’s machete was hanging from his belt as he walked through the growth.

“Just stay in his line. Step in his footsteps if you can.”

I looked at him. I was going to ask why, but he beat me to it. “Unexploded ordnance. Shells and stuff that didn’t explode. An average of five people a day die in this country from coming in contact with unexploded ordnance. And this is a bad area. Walk where he walks.”

No kidding. Unexploded ordnance. Doesn’t sound all that nasty. Oh, look a shell. Make a great souvenir. Think I’ll just … BOOM!

I hustled after Mr. Vinh at pretty close to a sprint. I didn’t want him out of my sight. This was one time I wasn’t going to argue with the old man. If he said walk in Mr. Vinh’s footsteps, that’s what I planned to do. I wondered whether the old man had mentioned unexploded ordnance when he’d talked Mom into letting me go on a little summer road trip.

We set out across the rice paddy. No hip waders this time. Just sloshing water up to your ankles and in your shoes and soaking your socks. Just as we got to the other side, a woman came running up to us. She was yelling and waving her arms. My guess was that she was pissed off about us walking through the rice paddy. Her rice paddy. I didn’t know if we had wrecked any of the plants or not — I’d tried not to — but I could see her point.

The old man kept walking, and I figured I’d better follow along. Don’t forget the unexploded ordnance. We left Mr. Vinh to deal with the rice paddy lady. Almost immediately we were once again surrounded by dense jungle growth and animal noises. This part of the jungle seemed noisier than any we’d been in so far. I wondered why that would be. The water maybe. Greater number of animals because of the water right close by. Although water didn’t seem to be something that was in real short supply in the jungle. We’d walked through lots of little puddles and pools.

The old man hadn’t been BS-ing. There actually was a path in this part of the jungle. It wasn’t very wide, and sometimes you had to duck your head, but it was a path.

Mr. Vinh caught up to us and went right by without saying anything. Took the lead again. I never found out what happened with him and the rice paddy lady after the old man and I got our butts out of there.

3

I’d had this piece of jungle figured right. It didn’t go for long, and pretty soon we were at the base of a hill. I’d lost track during our trek, but I figured this was the hill the old man had pointed to. Hill 453.

There were some trees and brush on the lower part of the hill, but it wasn’t nearly as dense as in the jungle. The old man spread one of the slickers on the ground and motioned for me to sit down. He pulled out the sandwiches — I’d almost forgotten about them — and passed them around. Mine was jam.

“Sorry, there’s no meat. I figured it would go bad in this heat, and we’d all get sick if we ate them.”

“Jam’s fine,” I said.

Mr. Vinh didn’t say anything, but he pretty much attacked his sandwich. And for the next twenty minutes we had this weird picnic, sitting on a slicker at the bottom of Hill 453. We polished off one entire canteen. All of us were thirsty.

After we finished eating, the old man dug out the briefcase again. This time he didn’t bother with the map. He mostly seemed interested in the photographs. He’d look at a photo, then at the hill, craning his head around like he was trying to get some sort of bearings. Mr. Vinh was mostly ignoring him. Kind of nodding off.

I watched, but I didn’t say anything.

“Okay, let’s go.” The old man stood up. He didn’t pick up the duffel bag this time. Just moved it over beside Mr. Vinh, who hadn’t moved a muscle except to unfasten the machete from his belt and hand it to the old man. It was obvious the old man and I were on our own from here on.

I wasn’t sure I liked that. Mr. Vinh knew his way around, that was clear. The old man hadn’t been here for forty years, couldn’t possibly remember. I was hoping he wouldn’t get us lost or up to our chins in quicksand or something. Is there quicksand in the jungle? Probably — right next to the unexploded ordnance.

He took the briefcase, and I grabbed the backpack and one canteen.

“Let’s go,” he said again.

We started across the lower face of the hill going up a bit of an incline as we walked. Okay, first of all, Hill 453 wasn’t really a hill. More like a mountain that hadn’t totally grown up.

I discovered this as the old man and I were working our way up the slope. It wasn’t too bad at first, not real steep and not tons of jungle growth. Neither of those lasted long. It got steep pretty fast, and at about the same time, it seemed like we were having to fight our way through major growth.

The old man stopped to catch his breath. Or maybe it was to let me catch my breath. “Triple canopy. That’s what you call jungle that’s got growth along the ground, at about head height and overhead as well. We’re in triple canopy here. Makes for hard going.”

Ya think?

A couple of times I lost sight of him but could still hear the swish-whack of the machete as he carved a path up the side of the hill.

It wasn’t long until I couldn’t see the sky at all. And a weird thing was happening. I was scared. Okay, maybe not scared but nervous. I still didn’t know what had happened here, but I had this strange feeling, like when you have the flu, and you’re hot, and then you’re cold. It just felt like this was a bad place.

I tried to stay behind the old man, but the truth is he could go up some places I couldn’t. Though the rain had stopped, the ground was muddy and slippery, and a couple of times I went down to my knees. There were some big palms to my right, and I figured I could use the leaves to pull myself up the slope.

I yelled. Loud. And jerked my hand off the first leaf. I was bleeding. The old man slid back down the hill to where I was and looked at my hand.

“You’re okay. It’ll bleed a bit, but it’s not poisonous or anything. I should have told you about those. Nipa palms. The leaves have sharp edges. But I guess you already figured that out.”

He pulled a not-very-clean piece of cloth out of a pocket and wrapped it around my hand. “This won’t stop the bleeding, but it should keep some of the mud out of the cut. The bleeding will stop on its own.”

He pointed to an area to our left. “It’s not quite as steep over there. We’ll go that way.”

“Yeah,” I said.

“You okay?”

“Yeah.”

“You’re doin’ good, Nate.”

For some reason I liked hearing him say that. I wasn’t at all sure I was doing good, but I wasn’t doing all that bad either. And I realized something. I hadn’t complained about anything, not really, for at least a couple of days. Ruining my image.

4

In the next half hour my guess was that we covered a hundred and fifty yards, maybe less. The only good part was that the old man was having as much trouble as I was. At least I didn’t look like a total jerk trying to get up that hill.

I’d pretty well forgotten about my hand, but the handkerchief had been a good idea. I lost count of the times I had my hands in the mud up to my wrists trying to get a little further up that slope.

I lost track of the old man again, this time for longer than the time before. Sometimes I could hear him, and I could see where he’d worked his way up the hill. I tried to follow as closely as I could his exact route. That whole unexploded shells thing had spooked me. I tried to look down too as I scrambled through the mud. But I wasn’t sure that I’d see anything even if it was there. It could be covered in mud. Or buried just far enough to be out of sight.

For most of this trip I’d been either bored or pissed off that I was there at all. That it was killing my well-planned summer. Now there was something else. There was danger here. An average of five people a day, the old man had said. And they probably weren’t scrambling through a battlefield on their hands and knees.

I called out a couple of times, but he didn’t answer. I wanted to stop. Every muscle was tired, and I was totally out of breath. Sweat was pouring out of me. And the old man wasn’t answering me.

Terrific.

I finally caught up, but only because he’d stopped. As I came up behind him, he was looking around. I couldn’t see that where we were looked any different from where we’d been twenty minutes earlier. And looking ahead, it didn’t look like the next twenty minutes would change much either.

But something was different. The old man was different. I flopped down on my side, propped myself on one elbow trying to catch my breath. I looked at him. He turned toward me, and what I saw scared me more than the idea of hidden exploding stuff.

His eyes were open wide, and he was making some kind of moaning noises. I was pretty sure he wasn’t seeing me even though I was five feet away at the most. I thought maybe he was having a heart attack or something. I wasn’t sure what I was supposed to do. What I could do.

“Are you okay?”

He didn’t answer me. I tried to get up to where he was, but I kept slipping back. Finally I was able to get my feet against some rocks and push my way up beside him. Both of us were covered in mud.

He was on his belly now, his head barely off the ground, looking up the slope. I reached out and took his arm. He jumped and grabbed me by the shoulder. Hard. Scared the crap out of me. He was looking at me like he was seeing something else. Maybe someone else. Someone he wanted to hurt.

“It’s me. It’s me, Nate. Nathan,” I told him.

I said some other stuff too, but I can’t remember what exactly it was. I still couldn’t tell what was wrong with him. But even through all the mud and stuff, I saw that his face was all changed. There was a look, no, not a look, not an expression, something more than that — it was like his face was all out of shape. Like he was in pain.

He wasn’t the only one. He still hadn’t let go of my shoulder. And it was starting to hurt like hell.

“It’s okay. It’s just me, Nate. Your son.”

It felt weird to hear those last words coming out of my mouth. I managed to get hold of one of the canteens, got the top of off, held it toward him. “Here,” I said.

I wasn’t sure he understood at first. But finally he let go of my shoulder and took the canteen. He twisted over on his side. Drank like he was someone in the desert. Like people you see in movies, the water rolling down the sides of their mouths.

5

After that he started to look more normal, breathe more normal. He passed the canteen back to me, and I took a drink, then twisted the top back on.

“You okay?” I asked again.

He didn’t answer, but I thought maybe he nodded his head, just a small nod, but something, I was pretty sure.

He took some deep breaths, trying to get himself back. He pulled himself off his belly and sat up, still looking around, but his eyes looked more like they usually did. Intense but not crazy. Not like they’d been a couple of minutes before.

“Over there,” he pointed. “Work our way over there.”

I looked where he was pointing. Up a little ways and to the right. The jungle growth did seem a little less there. There was nowhere for him to get by me, so I led the way this time. We slid our way up and over to where he’d indicated, to a bit of a clearing. Not as much mud there. It was steep, but there were a couple of trees, not nipa palms. I sat down in a small depression right next to one of the trees. I could kind of brace myself against the up-slope side to keep from sliding. It was grassy and fairly dry. Better. Almost comfortable.

We sat there close together, both still breathing heavy, sweating. Looking up the slope.

I was too tired to talk. I just wanted to breathe, but each breath hurt my chest. It was quite awhile before the old man said anything. When he spoke, it wasn’t much more than a whisper.

And he wasn’t talking to me. Not really. He was just talking.

“I was so scared here. So scared. I never knew a person could be as scared as I was that day. I’d been in firefights before, been shelled before, even wounded once, not much more than a scratch, but still I’d been in the heat of battle. I knew what it was like to have people shooting at me, trying to kill me. And I’d been afraid before, being afraid in a battle isn’t being a coward … but nothing like this. Nothing like here.”

He shifted his weight, leaned back against a tree trunk.

“It was an alpha-bravo, that’s the term we used for ambush. Bo Doi, Uniformed North Vietnamese Army regulars. Tough, well-trained fighters. Used to fighting in the jungle, and damn good at it.

“We were Delta Company, two platoons. Ninety men. Our platoon, we called ourselves The Fighting Ninth. Hadn’t really done all that much fighting. A few firefights, not big ones. But this was different, this was something not even the cowboys in our group, the guys who craved action — not even those guys wanted this. I figured Kiner, he was our sergeant, and maybe our lieutenant, maybe those guys had seen this kind of combat before. For the rest of us, this was a whole new ball game. We were scared, and we were fighting for our lives.”

He spoke slowly, his voice still barely more than a whisper. And it was flat, no emotion. Not like his eyes. His words were telling the story, but it seemed like his eyes were living it.

“I don’t know how many died in the first minutes. Fifteen, twenty, maybe more. We tried to fight back. Do what we were trained to do. Couldn’t see shit for the dust, the smoke, sure as hell couldn’t see Charlie. But he was out there, above us, on both sides of us. Maybe below us. We didn’t know.”

The old man stopped talking. Reached for the canteen, took another drink. Poured some over his face. He set the canteen down on the ground between us.

“The noise is the worst … what I hated most. One minute it’s so quiet you can hear the sweat running down your chest and the next minute you can’t think for the noise. That’s not some bullshit statement. You can not think. Guns, mortars. Guys on both sides yelling. Some screaming. The worst was ‘help me.’ Wounded guys yelled, ‘Medic,’ or ‘I’m hit.’ Dying guys yelled, or they whispered, ‘Help me.’

“I remember the lieutenant and a radio guy next to me, both of them yelling as loud as they could. Trying to be heard over the noise. Trying to get help. I remember some of it. Blue Water One … This is Blue Water Five … Blue Water One, this is Blue Water Five … Delta Company, Delta Company … Hill 453 south slope, alpha bravo, alpha bravo. Boo koo Bo Doi. Deep serious. Need close air support. Immediate. Repeat. Deep serious … deep shit. Need close air support and dustoff. Can’t give zulu. Need dustoff.

“But it didn’t matter how much shit we were in. The weather had closed in over us. Low cloud. Nothing that flew could even see the hill, let alone see us, or get our wounded men out. That’s called dustoff. Couldn’t even give a zulu … casualty report. Nobody knew who was dead and who was alive. All we knew was there was a lot fewer of us now than when we started.

“We got spread out … too far apart. Couldn’t communicate with each other. I saw a guy. Charlie. There were maybe a few hundred of them, and I finally saw one. Bet I fired forty rounds at the son of a bitch. No idea if I hit him.

“I was sure I was going to die that day. Right here where we are. This is where we dug in, tried to hold on. Still calling for help.

“I’d been in country for nine months. Lots of search and destroy patrols. That’s what they called it when you went looking for Charlie, so you could shoot his ass. Got wounded on one of those. I was point — the guy at the front.”

“Is that the scar on your neck?”

He nodded. “Trouble was the only time you found Charlie was when he wanted you to find him. When he was hidden and ready. Like he was that day. Here. I remember looking back down the hill, and the lieutenant and the radio guy, Cletis, they were both dead.”

He stopped talking again, took a couple of breaths, had a fit of coughing, then recovered.

I looked around again. All I could see was jungle. I tried to imagine what it must have been like that day. But I couldn’t, not really. All the movies I’d seen, it had to be like that, right?

But I knew that what the old man was talking about wasn’t like any movie I’d ever seen. I closed my eyes, but I still couldn’t see it. Scrunched my eyes tighter. And there was … something. So weird. I couldn’t see anything … but it was like I could hear it. Shooting, stuff exploding, people screaming. It scared me and I opened my eyes quick.

Silence.

“We’ll rest here.” The old man’s voice. “Let me see the rucksack.”

I pulled the backpack off my shoulders and passed it to him. He pulled a couple of oranges out of it and handed me one.

For a few minutes we didn’t say anything, just ate the oranges. When we’d finished, he pulled out a camera and took some pictures of the area around where we were sitting. He didn’t take any pictures of me and didn’t ask me to take any of him. This wasn’t a family holiday at the Grand Canyon.

He put the camera back in the backpack, pulled out a little folding shovel, and handed it to me.

“You’re sitting in a foxhole.”

“Foxhole, that’s what you dug and got down into, right?”

I looked down at the depression I was sitting in. I guessed it had filled in quite a bit since it was a foxhole for some soldier.

“Yeah. These ones weren’t very deep. We didn’t have much time. They were still shelling the shit out of us and giving it to us pretty good with AK-47’s at the same time. From over there was the worst.” He pointed to the right. The jungle was thickest there. Maybe it was back then too. “That’s where I saw that first guy I shot at.”

My butt was sore, and my back was getting stiff, so I shifted my weight. Tried to get more comfortable.

“Go ahead, dig right there, at the bottom of your foxhole.”

“What for?”

“Guys sometimes buried stuff there. Or just left it in the foxhole when they moved out. Or got killed.”

“I don’t know if I want to.”

“It’s okay,” he nodded. “Go ahead.”

I stood up and unfolded the shovel. “Where should I dig?”

“Anywhere. In the bottom of the hole.”

I dug. It wasn’t easy. There was grass and roots from the trees and other stuff growing around there. I didn’t really think I’d find anything. And at first I didn’t. But then there was something. I didn’t know what it was; it looked like part of a little tin can or something. There were words on the side, but I couldn’t make them out. I reached down, lifted it out of the hole … handed it to the old man.

He looked at it, then looked up at me, sort of smiling. “C rations. What we ate when we were in the field came in these little tins. This one was ham and lima beans, the worst shit they ever put in C rations. Every guy hated it. We called it ham and chokers. There were worse names too, but ham and chokers says it real well.”

He tossed the tin back to me. “Got yourself a souvenir.”

A souvenir. Something to make me remember a summer I wanted to forget. I handed the tin and the shovel back to him. He put them both in the backpack.

I sat back down in the foxhole. “Listen, I’m not pissed off or anything, but I’m still wondering why you brought me here.”

He did up the backpack, pulled it behind his head, lay back on it. “Sometimes the most important thing that happens in your life isn’t a good thing. This is the most important thing that ever happened to me. I wish I could say it was your mom. Or you. But it was this. I want you to know me. To know me you have to know this.”

“I don’t get why you were in that war. You … we’re … Canadian.”

“There were other Canadians who fought in Vietnam.”

“That doesn’t answer my question.”

The corners of the old man’s mouth turned up just a little. “The truth? I didn’t have anything else to do. My baseball career was over. I’d had a couple of jobs, hated them … I wanted to do something, have an adventure, care about something.”

“Yeah, I guess.”

“Don’t try to understand it, Nate. I don’t totally myself. I remember reading all this stuff about how if this place became communist, then all these other countries would too. They called it the domino effect. Back then communism, that was a bad word. I guess it still is, but then it seemed like a big deal to stop them from taking over this part of the world. And I thought, ‘yeah, that’s something I can do. That’s the thing I can care about.’”

He waited for a while before he said, “I had it completely wrong.”

“Can I ask you something?”

He smiled a bit bigger this time. “You already asked me some things. Quite a few things.”

“I know. One more.”

He nodded.

“In the war museum there were all these photos. A place called My Lai.”

His eyes narrowed when I said the name. He nodded.

I wasn’t sure how to say what I wanted to say. Without making him mad. “You ever … you know … ”

“Was I ever involved in something like My Lai? Is that what you want to know?”

I looked down at the ground.

“The answer is no. Nothing like that. My Lai happened after my tour was over, but it made all of us sick. All of us who had tried to do our jobs and knew the whole time that so many people back home hated what we were doing and then those guys go nuts and massacre all those people, those kids … babies … ”

“Sorry. I guess I shouldn’t have asked that.”

“Nate, I can’t sit here and say I didn’t do some things I wish I hadn’t done. War brings out the worst … and maybe sometimes the best in people. It wasn’t like I thought it would be — them and us, good guys and bad guys, white hats and black hats. There was a lot of bad shit happened on both sides.”

He paused, reached for the canteen but didn’t take a drink. “That doesn’t make My Lai right. I hate that those guys were on our side. I’m just saying there was stuff that happened that made me wish I’d never come here.”

I didn’t answer at first. He drank, then handed me the canteen, and I took a long drink. I wiped my mouth with the back of my hand. “Even though I’m here I’m not sure I understand very much about what happened in that war. I mean you want me to know this so I can know you, know who you are. But I can’t say if that’s happening.”

“I get that, Nate. I really do. I don’t know that I’ve figured out a lot of it myself. ”

“How did it end?”

“The war? We lost, plain and simple. America lost the stomach to keep fighting when most Americans didn’t know what it was they were fighting for.”

“I meant here.” I looked around us. “Hill 453. How did it end?”

It was a long time before he answered, so long that I thought we’d gone back to me asking about stuff and him not telling me. But that wasn’t it. I watched, and his face twitched a couple of times. He was looking away, into the trees. I figured he was seeing it again. But this time he seemed in control.

Finally, he took a deep breath, let it out slow, looked back at me. “We hung on until help got to us,” he said. “That’s the short answer. They could have overrun us anytime they wanted to. But they didn’t. I don’t know why. I’ll never know why.

“There was a thunderstorm that night. Real light show. They didn’t let up shelling, and it was the damndest thing, not being able to tell the difference between the thunder and lightning and incoming shells. Then, when the thunderstorm stopped, the shelling stopped. It was like it was all part of their battle plan.

“In the morning, the sky cleared, and they probably figured help would be coming. So they really let us have it. An hour or more … it was the … the worst yet. A lot of people died right around here that morning. We were sure we’d be overrun, and that it would happen any minute. It’s funny but I wasn’t as scared anymore. I guess once you’ve figured out that these people are going to kill you, you just want to make them pay for the privilege.

“We called again for close air support and this time a couple of Huns, F-100s, came in, blew the shit of the place.

“The Hueys were able get in for dustoffs, and we got the wounded out. A company of marines was part of the same mission we were on — Operation Blue Water. They started out as soon the word got out that we’d been ambushed. They arrived about mid-morning. Army hates being rescued by marines, but I was just fine with it.”

“So that was it.”

The old man shook his head. “No, that wasn’t it. To show you how screwed up that war was, after all that we’d taken in that twenty-four hours, we got orders to move out. Take the summit; that was our orders, with the marines in reserve. We had sixty, maybe sixty-five guys left, and we were told to take the summit of 453.”

“What did you do?”

“We took the summit. The Huns made a few more passes, and we began an assault on the top. It took three hours, more guys died, maybe a dozen or so … a few others wounded. When we made it to the top, there were forty-seven people left in Delta Company.

“Half what you started with.”

“Yeah. When we finally got up there, there wasn’t a leaf left on a tree. It looked like something from a science fiction movie. A few blackened sticks poking out of the ground. That’s all that was left of jungle that was as thick as this until that day. And Charlie was gone too. We got up there, and we were by ourselves. There were eleven bodies from their side up there. I’m sure there was a lot more dead than that, and they’d taken the bodies with them when they left.”

“You and Tal … you were okay, you weren’t wounded?”

“We were … okay. I took shrapnel in the hand. I didn’t think it was bad, but it was bad enough that I spent the rest of my tour in Saigon. And Tal …”

He was staring off into space again, and his face was contorted. Like it had been before. I knew this was something I couldn’t ask him about. But he told me anyway.