Читать книгу First They Took Rome - David Broder - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

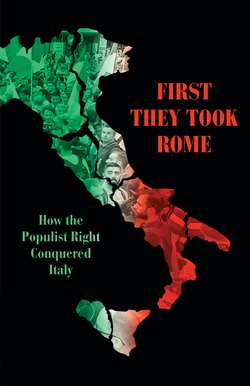

The Pole of Good Government

Even before the election was called, the insurgents’ antics in the Chamber of Deputies illustrated their rising confidence. As evidence mounted of the former prime minister’s criminal ties, one Lega Nord MP even waved a noose at the government benches. And when Italians did pass their verdict at the polls, they issued a withering condemnation of the establishment parties. More than two-thirds of incumbent MPs lost their seats, as an anti-corruption movement founded just three years previously became the biggest party in the Chamber of Deputies. The Lega Nord’s venom against the ex-Communist centre-left complemented its war on the bankrupt traditional right, whose MPs it now unseated across the upper part of Italy. Identifying its own electoral offensive with the magistrates’ exposal of a vast web of bribes and kickbacks, the northern-chauvinist party promised to impose its radical agenda on a new populist administration.

This isn’t a description of Matteo Salvini’s breakthrough in 2018, but of a political revolution that took place a quarter century previously. In the 1994 general election, Umberto Bossi’s Lega Nord – an alliance of six regional leagues that formed a single force at the end of the 1980s – elected more MPs than any other party, taking 117 seats in the 630-member Chamber of Deputies. Based on 8.5 per cent of the vote, the Lega Nord’s tally owed to the geographical concentration of its support – and despite its seat numbers, it entered government as a junior partner in Silvio Berlusconi’s coalition. Yet its anti-political sentiment had attracted broad-based support in Italian society, as it united a populist deprecation of political elites with the free-marketeer call for a Thatcherite revolution in Italy. Bossi’s party portrayed itself as the voice of the productive, modern North in rebellion against ‘thieving Rome’ and the ‘lazy, corrupt South’.

By 2018, the Lega was a rather different beast – it had become an all-Italian nationalist party, indeed a nationwide challenge to Berlusconi. Yet its success under Salvini’s leadership would have been impossible without the fortresses it built in the 1990s. In the 2018 general election, when 50 per cent of all votes went to either the Movimento Cinque Stelle (Five Star Movement; M5S) or the Lega, this was widely characterised in terms of the death of the traditional parties. Even taken together, the centre-left Democrats and Berlusconi’s Forza Italia had totalled just 33 per cent of the vote – M5S leader Luigi di Maio could declare the demise of the ‘Second Republic’ dominated by these forces. Yet a look at the events of 1994 exposes the shallow roots of these ‘established’ parties – and a longer period of volatility that allowed the populist right to begin its rise. The 2018 general election is easily presented as a unique moment of turmoil, given that 65.9 per cent of incumbent MPs either quit or lost their seats. Yet this was in fact slightly less than the legislative turnover witnessed in 1994 (where 66.8 per cent of MPs were ejected), and similar to that seen in the last contest in 2013 (65.5 per cent).1

When we understand this longer period of upheaval we also begin to doubt the suggestion that the M5S–Lega pact sealed in June 2018 represented Europe’s ‘first all-populist government’.2 For the anti-political sentiment that is today spreading across the West emerged in Italy not only at the moment of Trump and Brexit, but a quarter century previously. Already back then Italy had seen the destruction of the ‘First Republic’ that had taken form after World War II, a republic whose parties – the Christian-Democrats (DC), Socialists (PSI) and Communists (PCI) – each reached the end of their respective histories between 1991 and 1994. These parties’ disappearance decisively cut the ground from underneath the Italian political system – and prepared the way for its reconstitution on new and less stable bases.

Indeed, if after the M5S’s success in the March 2018 general election Di Maio claimed that citizen power had triumphed over ‘establishment’ parties like the Democratic Party (PD) and Forza Italia, the forces thus swept aside were in fact ephemeral products of the last couple of decades. If in the 1990s these parties reproduced a classic binary between centre-left and centre-right, they also reflected the post-modern times that followed the end of the Cold War, with the demise of the long-prevalent Communist and Catholic political families. These new forces’ life has, instead, been marked by radical shifts in the political landscape, from Italy’s integration into a new European order to the decline of the labour movement and the hollowing out of the old mass-membership parties. Faced with a seemingly perpetual crisis, a series of saviours have emerged promising to stabilise the state again, from Silvio Berlusconi to former central bankers and even Matteo Renzi. In this sense, Matteo Salvini’s Lega is just the latest force that promises to restore order in place of chaos.

The end of the First Republic was no single event – and was shaped by the frailties that had long built up in the Christian-Democratic-dominated state that emerged from World War II. The death of this order in the early 1990s married such developments as the Communist Party’s self-dissolution, the felling of the Socialists and Christian Democrats by anti-corruption magistrates, the acceleration of European integration, and the rise of Berlusconism. But as the old party containers collapsed, the Italian political system would have to be founded on new bases – and the forms it took showed just how far the ties between parties and society had weakened. This laid the basis for a new series of political forces – including a radicalised right, breaking from the Christian-Democratic past.

With the death of the forces that had dominated public life since 1945, mass-membership parties gave way to a series of ‘saviour’ figures from outside the world of politics, as judges, technocrats, and TV performers all promised to drain the swamp of corruption in Rome. The death of the First Republic was not an edifying spectacle – but it certainly was a spectacle. This was visible right from the opening act of its demise, the ‘Clean Hands’ trials that began in 1992. Exposing the web of kickbacks and embezzlement that had built up under the ancien régime, the trials turned the investigating judges into celebrities, as their cross-examination of leading politicians was beamed into Italians’ living rooms. Yet the effect was to feed a deep popular cynicism in political action itself.

Clean Hands began in 1992 not because of some sudden spike in corruption, so much as the destabilisation of Italian politics at the end of the Cold War. This largely owed to the dissolution of the Communist PCI in 1991, a development that had, at first, promised to lower the stakes of political combat. The perceived threat from the Communists – Italy’s second-most-powerful party – had long favoured elite connivance, serving both as an enemy to unite against and a reason for the other parties and their media outriders not to delve too deeply into each other’s affairs. However, the disappearance of this Communist bogeyman undermined the historic solidarity between Italian elites and parties like the Catholic DC and the soft-left PSI, which immediately came under intense scrutiny. But if the PCI’s historic rivals now felt freer to start throwing mud at one another, this did not leave public life any cleaner. Rather, the destruction of the old mass parties opened the way to forces that even more blatantly conflated public and private interests.

This was epitomised by media tycoon Silvio Berlusconi, who entered the political stage in 1994. His project was to recreate the Right around his own person, while also exploiting the wider atmosphere of deregulation and liberalisation. He galvanized his base with vehement attacks on ‘Reds’ and ‘communists’ – the centre-left in turn denounced Berlusconi’s vulgar personal conduct and debasement of public life. Yet many of their ideological assumptions were surprisingly similar. In 1991, the Communist Party had, as if apologetically, changed its name to Democratic Party of the Left; the former adepts of Lenin and Antonio Gramsci soon styled themselves not as partisans of labour but as the aspiring managers of a lean, clean, and pro-business institutional machine. It would in coming years repeatedly lend its parliamentary support to technocratic administrations, even appointing unelected central bank administrators as ministers in its own governments. Under the powerful influence of the Communist and Socialist left, the Constitution promulgated in 1947 had declared Italy a ‘democratic republic founded on labour’ – putting an at least rhetorical emphasis on the interests of working people. In its liberalised, 1990s form, the centre-left instead altered the Constitution to entrench balanced budgets and sobriety in the public accounts.

The First Republic had been no golden age, and its ignominious downfall was no conspiracy. As journalist Marco Travaglio summarily put it, the trials which exposed Bribesville took place ‘because there had been a lot of bribes’. Yet, as Eric Hobsbawm said of the dissolution of the Communist Party, the effect of breaking up the mass parties was in many ways to ‘throw out the baby and keep the bath-water’,3 replacing corruption-ridden parties with personalised forces whose internal affairs were even more inscrutable. Far from strengthening Italian democracy, the destruction of the First Republic instead opened the way for a wholesale attack on the institutional and cultural inheritance of post-war Italy, from employment rights to anti-fascism and even the role of the Constitution itself. Indeed, the greater effect of the wave of anti-political sentiment was not to hand power back to ordinary citizens, but rather to prepare the way for reactionary, privatising, and even criminal forces able to exploit the void at the heart of public life. The ‘liberal revolution’ promised by the parties of the Second Republic would, in fact, prepare the perfect breeding ground for the Lega.

Addio, Prima Repubblica

The idea of numbering republics might seem rather strange – indeed, it is the invention of Italian journalists, seeking to delimit changes of the political times, rather than part of the state’s official name. This habit comes from across the Alps, where France is today on its 5ème République. In that country, four other republics have surged and crashed since the monarchy was first felled by the French Revolution. These states’ history has, on each occasion, been bracketed by crises in France’s place in the international order, whether due to the threat of invasion (1793), military defeat (1870, 1940, 1958), or revolution across the European continent (1848). These upheavals each brought a different constitutional regime that proposed to impose order over tumult – on three such occasions, the new republic came after a period of restored monarchical rule or foreign occupation. In Italy, the transitions from First to Second and Third Republic entailed no such violent breaks, or even constitutional change. But in each instance, the power sharing between the main parties ended in their collective collapse, and the rise of a new party system framed by different ideological imperatives.

Like their French counterparts, Italy’s republics have tended to stand or fall based on the country’s international position. The First Republic emerged from the fall of Mussolini’s empire, and its politics were essentially determined by the Cold War divide, first visible in the competing influences of the US–UK armies and mostly left-wing elements of the Resistance that had helped free Italy from Nazi–Fascist rule. In postwar months, the main forces that had gathered in the National Liberation Committee (the DC, the PCI, and the Socialist PSIUP) together wrote a new democratic constitution, bearing a spirit of progress and anti-fascist unity. Yet, already before the document was enacted, DC premier Alcide de Gasperi’s spring 1947 visit to the United States augured a political realignment. Returning bolstered by promises of Marshall Plan investment, he kicked the PCI and PSIUP out of the ruling coalition, leaving his own party as the pivot of all future governments.

Hopes that the Resistance would drive a deep renovation of Italian institutions were rapidly thwarted. The House of Savoy’s attempts to backslide from its two-decade pact with Benito Mussolini were not enough to save it in the June 1946 referendum, when Italians narrowly voted to abolish the monarchy. Yet the immediate postwar years brought an amnesty for most Fascist-era crimes, thanks to legislation authored by PCI leader and erstwhile Justice Minister Palmiro Togliatti in the name of restoring social peace. Just 1,476 of 143,871 Fascist-era officials examined by the purges commission were removed from their posts.4 At the same time, the myth of a unanimous national Resistance had the perverse effect of avoiding a reckoning with the past, not only sealing the legitimacy of the partisan minority but also exculpating the passive-to-collaborationist mass. After the end of the Resistance coalition in 1947, it was, instead, the Communists themselves who came most under scrutiny.

The end of the war and the economic ‘miracle’ of the 1950s and 1960s were a moment of rapid industrialisation with few parallels in Europe, feeding optimism that Italy was leaving the bad old days behind it. Its stagnant institutional politics nonetheless lagged behind the many other modern-ising drives within Italian society. This particularly owed to the dominance of the DC. Not only could the party count on a solid base in the Catholic middle classes and rural South – guaranteeing it 35–40 per cent of the popular vote in each general election – but it enjoyed a US-backed stranglehold over the national institutions, as Italian NATO membership effectively forbade ministerial roles being entrusted to the PCI. Yet the DC did not have everything its own way. Its 1950s bid to legislate an automatic majority for the largest party was thwarted by smaller parties, and subsequent decades of coalition rule were marked by a constant balancing act between the democristiani’s internal factions and various minor-party allies.

This system faced a first major test in 1960, with an episode that threatened to bring the neofascist Movimento Sociale Italiano (Italian Social Movement; MSI) into the mainstream. In the 1950s, this party founded by Mussolini nostalgists had drifted from anti-American and rhetorically anti-capitalist positions toward the search for alliance with DC hardliners, in which vein it gave its outside backing to two democristiano cabinets in the late 1950s. In 1960, when the Partito Socialista Democratico Italiano (Italian Social-Democratic Party, a party of anti-communist social democrats) pulled out of their alliance with the Catholic centre party, the DC was left without a majority in parliament; appointed prime minister on 26 March 1960, the DC’s Fernando Tambroni thus formed a cabinet reliant on neofascist votes. Though the MSI was offered no ministerial roles, the signs of its emboldening – and its provocative bid to hold its congress in anti-fascist Genoa – sparked widespread opposition and even rioting. Over summer 1960, some eleven people were killed by police during anti-MSI protests.

However, this crisis ultimately served to marginalise the far right. The instability that Tambroni had fostered soon provoked a revolt among DC grandees, and by July they had forced him out of office, never to return to alliance with the MSI. Instead, the movement stretching from the industrial North to the Mafia-plagued farms of the South marked the onset of a class revolt not seen since the Resistance, which also helped impose a wider cordon sanitaire against the neofascists. Wary of further such disturbances coming from the left wing of the political spectrum, more liberal elements of the DC instead decided the time was right to integrate the Socialists into the so-called centrosinistra pact, in a ‘modern-ising’ arrangement that both preserved and renewed the DC’s central role to all coalition-making. Only in the 1980s would the DC hand the prime minister’s job to the centrist Republicans and later the Socialists ; it in all cases remained the dominant force in each cabinet.

The constant coalition-making was weakly responsive to electoral pressure. As journalist Paolo Mieli has noted, since national unification in 1861 the Italian electorate has only been able to impose a direct exchange of power between Left and Right twice (in 1996 and 2008), and it did not do so once during the First Republic (1948–92).5 The constant rise in the Communist vote from 1948 onward (first set back only in 1979) instead drew the other parties into closer cooperation. Able to treat the Italian state as if it were their own property in a ‘blocked democracy’, they operated on the basis of the Cencelli system, so named after a democristiano functionary who proposed dividing up ministries and public posts among party factions according to size, on the model of shareholders. This allowed them to share out not only government jobs but also control of tendering processes and influence over state agencies like public broadcaster Radiotelevisione italiana (RAI), on the basis of interparty agreements.

This cartelisation reached its peak in the 1980s, as the governments of the pentapartito alliance brought smaller and weaker rooted parties into institutional power-sharing. This five-party administration included all the main parliamentary forces except the Communists and neofascists and, in 1983, allowed the appointment, for the first time, of a Socialist prime minister – Bettino Craxi. The pentapartito epitomised the way in which the First Republic’s dominant forces could divide up posts and influence among themselves, indeed increasingly becoming factions integrated into the sharing of institutional power, rather than mass-membership parties. Craxi’s tenure marked a notable shift to the right for the Socialist Party, which both renounced its historic ties to Marxism and more sharply distanced itself from Enrico Berlinguer’s PCI. Yet he would enter the collective memory less as a heretic on the left than an embodiment of the corruption that brought the First Republic to its knees.

We have noted that Italy’s republics have tended to stand or fall based on the country’s international position. The end of the First Republic especially owed to the end of the Cold War, in particular insofar as the collapse of the Eastern Bloc served as the trigger for the dissolution of the PCI. Later, we will look more closely at the PCI’s demise and the consequences this had for the broader Italian left. Its immediate effect, however, was to undermine the solidarity on the other side of the political spectrum, among forces long cohered by their anti-communism. In autumn 1990 came revelations of Gladio, the so-called ‘stay-behind operation’ that NATO had developed in order to prepare military resistance to a PCI coup or Soviet invasion. When President Francesco Cossiga, in one of his characteristic outbursts, openly admitted his role in Gladio, the left-wing parties demanded his impeachment, soon forcing his resignation. Yet as Cossiga himself noted, once the Berlin Wall had fallen, the forces ‘pushing from the other side’ – notably the DC – were not going to be left standing either.6

The downfall of the old edifice began in 1992 with the arrest of the Socialist Mario Chiesa, a leading light in the Milan PSI. As administrator of the city’s Pio Albergo Trivulzio nursing home, Chiesa received tens of millions of lire in kickbacks from the cleaning company boss Luca Magni in exchange for contracts. When Magni, unable to withstand the mounting payments, finally reported the situation to the magistrate Antonio di Pietro, a sting operation was set in motion against the corrupt machine politician. On the early evening of 17 February, Magni entered Chiesa’s office with a secret microphone and camera; when the Socialist agreed to the transaction, as expected, the carabinieri burst into the room. Alarmed, Chiesa bolted into the toilet with the 37 million lire (about €20,000) in cash from another bribe, which he then attempted, in vain, to hide in the cistern. As the news spread across the TV networks, party boss Bettino Craxi tried to dismiss Chiesa as a ‘lone crook’: the Milan PSI, in the nation’s ‘moral capital’ was, after all run by ‘honest people’.

Not all were convinced. Already in a May 1991 article for Milan magazine Società civile, the magistrate Di Pietro had written of a mounting climate of impunity – in his view, public tendering should be characterised

less in terms of corruption or abuse of office than an environment of illegal payments, an objective situation in which those who have to pay no longer even wait to be asked for it, knowing that in this climate bribes and payoffs are customary.7

As far back as 1974, the scandali dei petroli had exposed the corrupt dealings between oil company bosses and leading politicians. But what more dramatically broke the political system apart in 1992 was its loss of internal solidarity. Cast off by his party and thrown in jail, Chiesa soon began to talk, revealing the vast web of bribe money that the PSI had orchestrated. As the ‘Milan pool’ judges picked up the men he named, a domino effect developed, and party underlings informed on others to save themselves. Of 4,520 people investigated in Milan, 1,281 were convicted, 965 through plea bargains.

Tearing through the webs of connivance within the old party machines, the Clean Hands process was marked by a robust judicial activism. As judge Francesco Saverio Borrelli said of the politicians investigated, ‘we imprison them to make them talk. We let them go after they speak’. However, the spectacle surrounding the cases and the magistrates’ rise to public prominence fed their own direct integration into the political field itself. The televised cross-examinations, and especially Di Pietro’s brusque tones in the courtroom, upended the First Republic’s characteristic etiquette, as stuffy institutional obfuscators were confronted by the crusading spirit of the prosecutor. This was also complemented by a kind of mob justice driven by media, not least as some of those on trial began to hurl muck at one another. When the Milan pool judges began a trial of local officials from the post-Communist Partito Democratico della Sinistra (Democratic Party of the Left; PDS), Lega leader Umberto Bossi proudly marched his supporters into the courtroom to shake Di Pietro’s hand before the cameras. The Lega leader himself soon admitted receiving massive illicit sums from the Montedison industrial group.

The image of the strident prosecutor-saviour, exposing the failings of a moribund party system on behalf of cheated Italians, was particularly brought into relief by the government’s feeble response. In a clumsy bid to slow the tide of arrests, on 5 March 1993 the administration led by PSI premier Giuliano Amato issued the Decreto Conso, which sought to turn ‘illicit party financing’ from a criminal to an administrative offense. This decree moreover contained a ‘silent clause’, which would effectively have allowed it to apply retroactively, thus cutting short thousands of Clean Hands investigations. The Milan pool judges responded with a televised address warning the public of what this really meant, and amid the ensuing uproar the president refused to sign off the government’s text. Instead, the political crisis deepened, with news on 27 March that the Palermo public prosecutor was investigating one of the First Republic’s linchpins, former DC premier and long-time minister Giulio Andreotti, for Mafia ties. The party system was being brought to its knees.

The malaise spread across partisan divides – and fed calls for a change in the forms of politics. This was particularly expressed in criticism of party lists – the electoral system by which candidates favoured by party machines could be guaranteed election to parliament. An institutional referendum on 18 April saw more than four-fifths of voters back a new system, favouring first-past-the-post contests more akin to the US and UK systems. With 75 per cent of seats distributed on such a basis, the new Mattarellum law promised to hand voters direct control over individual officials at the local level. Yet the sitting parliament remained under control of the established parties, and even after Amato’s government resigned on 21 April, the Chamber of Deputies was in self-preservation mode. On 29 April, a lower house over half of whose members were under judicial investigation voted to shield Craxi from prosecution. The editor of La Repubblica, Italy’s leading daily, called it the darkest day in postwar history – when the PSI leader appeared outside Rome’s Hotel Raphael, he was angrily confronted by coin-throwing demonstrators shouting ‘Why don’t you take this, too?’ Craxi’s reply was simply to accuse rivals of hypocrisy – in decades past, after all, the PCI had taken money from Moscow. But the First Republic, too, was about to go the same way as the Eastern Bloc states.

TV Populism

The April 1992 general election, held just weeks after Mario Chiesa’s rush to the toilet, came too early to be determined by Clean Hands. The big losers were, in fact, the heirs to the Communist Party, reeling from both the break-up of the PCI and a wider liberal triumphalism surrounding the demise of the Soviet Union. The first real sign of the post– Clean Hands political dynamics instead came with the local elections held in June and November 1993, where, for the first time, Italians directly elected city mayors. The Christian-Democrats were everywhere defeated, securing only 12 per cent of the votes cast in the capital; the dominant party here was instead the post-Communist PDS, which took Rome and Naples as well as backing the winning candidate in Turin. Yet the most remarkable news came in Milan, where the Lega Nord romped to victory, and with the advances for the postfascist MSI. This far-right party made the run-offs in both Rome (where it took 47 per cent in the second round) and Naples, where Alessandra Mussolini garnered 44 per cent of the vote. If the elections most of all saw the old government parties punished, the second-round ballottaggi had also shown conservatives’ willingness to rally behind even postfascist candidates to block the PDS.

This also heralded a wider realignment on the right wing of Italian politics. Indeed, if the PDS scored major local successes, the collapse of Christian Democracy was also opening the way for other forces – not just those carrying forth the message of Clean Hands, but also those who sought to put a stop to it. This was particularly evident in the intervention of one of Craxi’s long-standing allies, the billionaire TV entrepreneur Silvio Berlusconi. Long an associate but not a member of the PSI, his allegiances instead lay with the Propaganda Due masonic lodge, a fraternity that united mainstream politicians with mob bosses and far-right terrorists. Having come under investigation for his ties to organised crime – and faced with a likely PDS victory in the coming general election – the tycoon sought an immunity for himself rather like that which Craxi had briefly secured. On 26 January 1994, Berlusconi issued a televised address announcing that he himself would ‘enter the field’ (scendere in campo) in the attempt to save Italy from ‘the Communists’. The general election called for 27 and 28 March would represent his first test at the ballot box.

The televised address that Berlusconi made from his office on 26 January 1994 was a striking intervention in public debate – Antonio Gibelli estimates that by the end of that evening some 26 million Italians had watched the speech, in whole or in part.8 But the entrepreneur’s decision to take to the field – and particularly his way of presenting it – also augured a new era in Italian politics, characterised by the cult of the reticent popular hero. In his address, the billion-aire cast himself as a humble son of Italy who had only reluctantly entered public life, unwilling as he was to live ‘in an illiberal country governed by men [the former Communists] double-bound to an economically and politically bankrupt past’.9 Berlusconi made ample reference to both his business experience and his newness to public life, an ‘anti-political’ message strengthened by his invocation of the needs of gente comune (‘ordinary folks’) rather than the more cohesive popolo. Berlusconi called for an end to party politics, a new era in which Italy would be governed by ‘wholly new men’ – his would be a ‘free organisation of voters’ – rather than the ‘umpteenth party or faction’. As against the ‘cartel of the forces of the Left’ (deemed ‘orphans of, and nostalgics for, communism’), he called for a ‘pole of freedoms’ to unite private enterprise and ‘love of work’ with the family values of Catholic Italy.10

The folksier tones of this message fed on a popular loss of faith in institutional elites. Yet Berlusconi’s message also called for a stop to the turbulence created by Clean Hands, here coded as a return to ‘calm’. He portrayed the PDS in terms of militancy and disruption, indeed in the most classically anti-Communist terms, accusing the party of seeking ‘to turn the country into a fulminating street protest [piazza], which shouts, rants, condemns’. While Berlusconi pointed to the failings of the ‘old political class’, he smoothed over the specifics of Bribesville, instead collapsing it into the trip-tych of ‘criminality, corruption and drugs’ and the high public debt run up in recent years. The problem, it seemed, was not the actual parties of government, but rather ‘politics’ as such, from ‘the Left’ to the ‘prophets and saviours’ whom the trials had brought to the surface. What could, however, ‘make the state work’ was a businessman of broad experience. Given this enthusiasm for putting business values into politics, it was no surprise that his candidates in 1994 were dominated by employees of his Fininvest and Publitalia companies.

This regeneration of the right would have been impossible without Berlusconi’s pre-existing political ties. Indeed, his media power, rooted in privatisations that had begun in the late 1970s, also owed specifically to his association with the corrupt Socialist prime minister Craxi. Under the First Republic, the public broadcaster RAI had held a monopoly on national television, but this was chipped away over the 1970s with the granting of licenses to supposedly ‘local’ stations like Berlusconi’s Telemilano, which, in reality, broadcast nationally. Already by 1983, his channels sold more ad space than the RAI, and after a legal challenge in 1984–85, Craxi issued the so-called decreti Berlusconi to put a formal end to the monopoly. Where RAI was governed by the demands of public-service broadcasting, the tycoon’s stations instead served up a diet of escapism, promoting the sovereignty of the consumer and a Gordon Gekko–style image of success. The tacky glamour promoted by prime-time chat and US soaps was allied to the carefree materialism of the game show. Some, like comedian Beppe Grillo (cast out by RAI after his trashing of Craxi), refused to appear on the billionaire’s channels. But Berlusconi had a platform to address tens of millions.

In this sense, it soon became clear that the judicial offensive against ‘the parties’ had opened the way to powerful and well-structured forces even less democratic than their First Republic predecessors. Berlusconi’s Forza Italia vehicle – a creation of his media empire in which he personally picked the candidates – had neither local branches, members, party congresses or internal elections. In the 1994 general election it was also allied to other radical forces, from Umberto Bossi’s Lega Nord to Gianfranco Fini’s MSI (now rebadged Alleanza Nazionale, National Alliance; AN). These parties like Berlusconi each vaunted their credentials as ‘outsiders’ who stood against the political legacy of the First Republic. Yet, in truth, they merely represented different souls of the Right. While Berlusconi’s televised address had augured a Thatcher-style revolution in Italy (‘liberal in politics, free-marketeer in economics’), this stood at odds with the more paternalist hues of the AN and small centrist forces; the Lega Nord, based in the heartlands of the wartime Resistance, in turn refused to enter any direct alliance with the postfascists.

Berlusconi’s coalition soon took a lead in the polls – trashing any hopes that Clean Hands might have paved the centre-left’s own path to high office. And the result of the March 1994 election was the destruction of the parties that had ruled Italy since World War II. The right-wing coalitions built around Forza Italia amassed some 16.6 million votes, as the candidates of Berlusconi, Bossi, and Fini drew almost 43 per cent support. This was a massive blow for the PDS, whose Alliance of Progressives scored just 13.3 million votes (34 per cent); the surviving trunks of the old DC, a party that had been the largest party of government without interruption from 1944 to 1992, won the backing of only 6.1 million Italians, less than 16 per cent of the total. Aside from the sheer speed of the new right’s breakthrough, the result was also remarkable for the distribution of seats. Held under the new electoral law11 passed by referendum in April 1993 – with 75 per cent of seats assigned on the basis of first-past-the-post – the March 1994 contest made the Lega the largest single party in the Chamber of Deputies and gave Berlusconi and his allies a hundred-seat majority, though they fell marginally short in the Senate.

Rehabilitating the Far Right

Such a rapid electoral triumph was impressive for a man who claimed that he had ‘never wanted to enter politics’. Indeed, this claim pointed not only to Berlusconi’s ‘outsider’ status, but also his opportunism in entering the public arena. From the start of his reign, it was obvious that he had sought high office in order to shield himself from fraud and racketeering charges, both exploiting the political chaos created by Clean Hands and trying to protect himself from it. The Biondi bill of July 1994 – a bid to put an end to Clean Hands, ultimately felled by the Lega (after some equivocation) – was a first, failed, example of the ad personam legislation that Berlusconi used to shield himself and his underlings from prosecution. Where the old parties’ local sections, internal elections, and congresses had been polluted by conflicts of interest, Forza Italia was overtly a web of business associates personally dependent on Berlusconi’s empire. At the same time, while the tycoon took his distance from the mass parties of the First Republic, he also took sharply different attitudes to the two forces that had been excluded from high office – the Communists and the neofascists.

When Berlusconi heralded the end of the Cold War as the triumph of liberal values, this looked a lot like a shift to the right, indeed a throwback to a previous age of anti-communism. Indeed, whereas he characterised his own right-wing coalition as ‘liberal and Christian’, anyone who opposed it was labelled a ‘communist’. The neofascist MSI had long claimed that the state, the universities, and public television were overrun with Communists; this same myth was now used by Berlusconi to smear anyone who challenged his interests. For the billionaire, the PDS, the magistrates, and his critics at The Economist were part of one same ‘Red’ establishment: he even labelled this weekly spigot of free-marketeer liberalism The Ecommunist. Curiously, the dissolution of the actually existing Communist Party allowed Berlusconi to apply this label all the more indiscriminately. In 2003, he staged a photo op brandishing a fifty-year-old copy of l’Unità with the headline ‘Stalin Is Dead’, cocking a snook at the supposedly ‘real’ sympathies of his opponents.

Berlusconi’s crude re-assertion of anti-communism was also the basis for the rehabilitation of the far right, the ‘post-fascists’ who joined his so-called Pole of Good Government. As the 1960 attempt to create a Christian-Democratic government reliant on neofascist parliamentary support had shown, the cordon sanitaire against the MSI had never been a direct product of the ban on the Fascist Party, but rather owed to mobilised opposition. Over the 1970s, the MSI had remained Italy’s fourth largest party, winning up to 9 per cent in national elections; atrocities like the 2 August 1980 bombing of Bologna station, killing eighty-five people, also illustrated the violent threat from more militant neofascist circles around the edges of the MSI. In the 1990s, however, with the demise of the DC, the old camerati moved to adopt its positions as their own. At a party congress in 1987, MSI leader Gianfranco Fini had declared himself a ‘fascist for the 2000s’; by the time of the 1994 election, he had become the self-proclaimed ‘conservative’ leader of the new AN.

The ignominious collapse of the DC, combined with the lack of any mass party of the right, presented the space in which longtime fascists could reinvent themselves as a traditional conservative ally of the more ‘free-marketeer’ Forza Italia. Fini’s AN sought closer ties with the small ex-DC factions that had entered the right-wing coalition and also adopted more liberal positions regarding both the European project and immigration (which were now each accepted, but conditionally). This was a break from the MSI’s tradition – after all, its roots in the wartime Salò Republic and Mussolini’s rearguard struggle against both the Resistance and the US Army had imbued the party with a foundational hostility to the First Republic, and some currents within its ranks such as that led by Pino Rauti had maintained an ‘anti-systemic’ stance against NATO and European integration. In the 1990s, the AN however eschewed this ‘militant’ past, creating a socially conservative and pro-European party akin to Spain’s post-Franco Partido Popular.

With Berlusconi ready to admit that ‘Mussolini did good things, too’, the MSI’s leaders could wind down their obsession with Il Duce without having to repudiate their own roots entirely. The example of former MSI youth chief Gianni Alemanno, a key architect of the new centre-right, was telling. In 1986, the young fascist had been arrested for attempting to disrupt a ceremony in Nettuno, at which Ronald Reagan honoured the US troops who fell on Italian soil in World War II. Yet, by the time he was elected mayor of the capital in 2008, Alemanno was embarrassed to find his victory greeted by fascist-saluting skinheads outside city hall. He responded with an apparent gesture of contrition, paying a visit to Rome’s synagogue in which he extolled the ‘universal’ values of the fight against Nazism. Yet this was also a means to paint the anti-fascist element of the partisan war as a form of sectarianism: Alemanno decried the ‘crimes committed by both sides’ in the ‘civil war’ among Italians.

This relativist offensive against anti-fascist norms made progress in an era in which ‘politics’ had become a dirty word and in which the Resistance generation were ever less central to public life. There had always been revisionist narratives of Italy’s wartime history, seeking to put partisans and fascists on a more equal footing: but only after the fall of the First Republic did they became part of the common sense. This was particularly notable in the success of such works as the novelised ‘histories’ written by journalist Giampaolo Pansa. His series of works, beginning at the turn of the millennium invoked the ‘memory of the defeated’ – the silenced and calumnied defenders of Salò – as against the mythology with which the First Republic had garlanded itself.12 More broadly, revisionist narratives focused on the killings of Italian citizens by Yugoslav partisans, in the so-called foibe massacres; interest in this neighbouring country did not however extend to the far-greater numbers of Yugoslavs slaughtered by Italian troops. The purpose was a domestic, political one, in the bid to undermine anti-fascists’ claims to superior moral and democratic standing.

It seemed that the collapse of the old party order had brought a sudden rewriting of its origin story. Indeed, this offensive especially exploited the discredit into which the parties of the Resistance had now fallen. As il manifesto’s Lucio Magri put it, after the Bribesville scandal, the democratic republic born of 1945 was no longer bathed in heroism but damned ‘as the home of bribes and a party regime that had excluded citizens’; the largest Resistance party, the PCI, was remembered only as ‘Moscow’s fifth column’ therein.13 This narrative was even taken up by many who had long laboured in its own ranks. Exemplary was Giorgio Napolitano, who joined the PCI in December 1945 and embraced Stalinist orthodoxy before becoming a key leader of the party’s most moderate migliorista (gradualist) wing. In the 1990s, he sharply repudiated the party’s record, which he recast as a regime of lies unable to face up to its own essential criminality. As president from 2006, Napolitano went so far as to commemorate the Communist partisans’ victims in the foibe of north-eastern Italy, including known fascists.

The Lega Nord

Some anti-fascists did remain mobilised, unwilling to swallow the more flagrant misrepresentations of the republic’s founding values. This was visible as early as 25 April 1994, in the commemorations which marked the traditional anniversary of Italy’s liberation from Nazi–Fascist rule. When Lega leader Umberto Bossi attempted to join the Liberation Day march in Milan, just four weeks after he had helped elect the most right-wing government in decades, he was quickly driven away by protestors. The Lega Nord was not itself of Mussolinian origin: rooted in the Northern regions where the Resistance was strongest, it expressed a sometimes virulent hostility to Fini’s ex-MSI, refusing to seal any direct electoral alliance with the postfascists even when both parties were joined to Berlusconi’s Forza Italia. The Lega Nord leader later received a suspended jail sentence after an outburst when he suggested that his members might go ‘door to door’ and deal with the fascists ‘like the partisans did’. Yet Bossi’s initial promise that he would ‘never’ join a government that included postfascists proved short-lived.

Bossi’s ability to shift on such a profound question of political identity points to the highly contradictory and opportunistic character of the party he created, as volatile as the political times in which it came to prominence. Its origins lay in the late 1970s, when, spurred by the creation of regional governments, new parties took form in the wealthiest parts of Italy to demand more funds for their own regions. In the 1987 general election, Bossi was elected senator for the Lega Lombarda – a force active in the region surrounding Milan – and, in 1989, it merged with similar groups that had arisen in five other regions, united by a common decentralising agenda. A breakthrough in the 1990 local elections (where the Lega came second-place across Lombardy) showed that it was a force to be reckoned with, and in particular its ability to break through the class binary which had done so much to structure the First Republic’s political system. In 1991, the various leagues formed a single party, though, in some contexts, they also maintained their own regional names.

The leagues had made their first advances in regions that had once loyally voted for the DC. Key was a first breakthrough in Veneto, a strongly Catholic region of particular cultural idiosyncrasies, which had long enjoyed an outsized representation in DC cabinets. In the 1950s, this agricultural northeastern region was as poor as southern Italy and marked by similarly high emigration, but its rapid industrialisation over subsequent decades transformed it into the richest part of Italy.14 Yet as Veneto raced ahead, the local DC led by Antonio Bisaglia was accused of channelling the region’s taxes toward an overbearing central state, making local firms pay for its handouts in the less successful south. Where Bisaglia toyed with the notion of creating an autonomous party akin to Bavaria’s Christlich-Soziale Union, some local DC cadres went further, in 1979 forming the regionalist Liga Veneta. Building its profile over the 1980s, the Liga would soon exploit the crisis of the First Republic, coming second to the DC in Veneto in the 1992 general election.

Indeed, if the decline of the First Republic presented a vacuum, some ‘outsider’ forces caught the mood of the time better than others. In an insightful article remarking on the Lega’s early breakthroughs, Ilvo Diamanti highlights its capacities as a ‘political entrepreneur’ – a force which captures and mobilises the disillusionment with some other party, before using this base to conquer a broader popular hegemony.15 Both the Liga Veneta and Bossi’s Lega Lombarda at first saw particular success in areas long held by the Christian-Democrats but where the social glue provided by the Catholic Church was undermined by secularisation. This, however, also corresponded to a changing approach to public life, less defined by unifying cultural visions or even collective material demands, as by a transactional relationship between the atomised citizen and the state. This shift also had a particular class basis – indeed, the leagues were at first heavily based among (mostly male) small businessmen and their employees, categories in which the Lega still enjoys relatively high support. But as the Lega Nord became a more recognised political force, its identitarian appeal became more transversal – and its demography more representative of the areas where it is rooted.16

Because its rise has broadly coincided with the decline of the old left – allowing it to win elections even in historic ‘red heartlands’ – the Lega Nord is often erroneously presented as a ‘welfare-chauvinist’ party, namely one which claims that reducing migrant numbers is necessary in order to protect and extend the welfare state. Yet, despite its attacks on spending on migrants, the Lega Nord was from the outset also dominated by anti-statism and the call for sharp tax cuts. At its founding congress in 1991, Bossi explicitly connected his regionalism to the simmering discontent against the First Republic and its so-called ‘elephantiasis’.The Lega’s ability to transcend a purely middle-class electorate owed not so much to the promise of welfare as to the fact that it presented corruption as a characteristically ‘southern’ problem from which northerners of all classes could be liberated. Bossi told his followers that it was no surprise that the voter revolt against the First Republic had arisen ‘in the areas of industrial civilisation, where citizens’ relation to institutions is more critical – though it will come in the South too’.17 Indeed, even before the Bribesville revelations, the Lega was advancing much of what soon became the common sense about Italy’s institutions and in particular the need to break the power of a high taxation, a corrupt state machine weighed down by patronage, and clientelism.

The end of the First Republic had raised the importance of ‘anti-corruption’ in a contradictory and limited way. Contra the Lega’s own presentation, both the case of the Milan PSI and Bossi’s own behaviour shed doubt on whether abuses could be pinpointed to the South specifically. Indeed, if the Lega Nord’s path to prominence was eased by the demise of the old parties, it immediately moved to claim the same privileges – and more illicit benefits – available to its predecessors. In March 1993 Bossi marched his supporters into a Milan courtroom to shake hands with prosecutor Antonio Di Pietro, congratulating him for his moves against the local post-Communist PDS. However, within just months Bossi was himself in the firing line, as a fresh set of hearings – the Enimont trial – exposed the bribes that chemicals giant Montedison had made to figures across the political spectrum: Bettino Craxi, local DC members, and also the Lega leader. Appearing in court at the turn of 1994, Bossi admitted he had illicitly received money from the firm but insisted that he had provided nothing in return.

That Bossi survived this setback provided an early indication that the ‘anti-corruption’ on which the Lega Nord thrived wasn’t just about the kind of wrongdoing that could be tested in court. His party instead used this term as a more nebulous – and conventionally right-wing – attack on unearned reward and state profligacy, as exemplified by the invocation of poor southern regions leeching off the productive North. In this sense, the assault on corruption also adopted a curiously racialised dimension. At the Lega’s founding congress in 1991, Bossi explicitly described the party as ‘ethno-nationalist’ and labelled southerners – pejoratively termed terroni – as feckless layabouts to be identified with Arabs or Albanians rather than white Europeans.18 This cult of the industrious North was also married to a kind of folk nationalism, albeit one limited to certain regions. This party of industrial modernity adopted as its logo the sword-wielding figure of Alberto da Giussano, a mythical warrior who supposedly defended the Carroccio (a four-wheeled war altar) against Frederick Barbarossa in the Battle of Legnano in 1176.

The foundational clash with the First Republic (and indeed the PSI) assumed a lasting place in Lega folklore – as would the party’s nickname, the Carroccio. The Lega’s sense of territorial rootedness is especially bound to Pontida, a town of 3,000 people near Bergamo, in its Lombardian heartlands, where it made one of its earliest local election successes, during the final years of the First Republic. Responding to the Lega Nord’s breakthrough, PSI leader Bettino Craxi paid a visit to the town on 3 March 1990 in which he tried to pander to leghista themes, acknowledging the popular demand for a more federal Italy. Unimpressed, local Lega Nord activists jeered the former premier, and three weeks later Bossi and his comrades held their own opposing summit in Pontida. After their massive gains in the 1992 general election, the Lega faithful again met there for a three-day celebration. This set the precedent for a summer festival that continues to this day at which crowds of mostly white-haired Lega activists convene to consume rather grim quantities of meat and beer.

The ritualised return to Pontida typified the party’s roots in provincial northern Italy. Contrary to the general tendency of political forces in Italy and beyond, over the 1990s and 2000s, to replace territorial branches with media campaign vehicles, the Lega Nord built its initial rise on cadre structures rather reminiscent of the old mass parties. These were particularly important in ensuring its visible organisation presence even in small communities. Indeed, though the party was from the outset a recipient of funds from the great industrial groups of the North, the Lega Nord’s electoral rise was driven not by wealthy urban populations – as heralded by some former Marxists who hailed the liberation of ‘dynamic’ northern Italy from the ‘backward’ South – but, rather, by the small towns and hinterlands surrounding these same cities. While it would capture the largest regional governments in northern Italy in 2010, the Lega has in fact never occupied the mayor’s office in such major urban centres as Turin, Genoa, Venice, Trieste, Bologna, or Brescia. If, amidst the collapse of the First Republic, it managed, in 1993, to capture the largest of all northern cities, Milan, it has never since won elections there, its largest conquests instead coming in mid-ranking cities like Verona and Padua.

In Lega members’ own accounts of why they joined the party, there is a strong promotion of both identity – the system of values that build a community – as well as the notion of being in contact with the population, where other parties have become more focused on media campaigns. In a Lega-sympathetic collection of testimony by Andrea Pannocchia and Susanna Ceccardi, one youth activist explains, ‘The others look at us astonished because they don’t have activism like this, by people active on the ground, holding gazebos, doing sit-ins, holding demonstrations and organising events’;19 or, as one activist put it, a ‘school of life’ running through activism.20 A lawyer in Varese running a Lega-attached cultural association explains, ‘It is a world of young people, professionals, entrepreneurs who perhaps don’t want to dedicate themselves directly to politics but are interested in defending our territories’ culture and environment’.21 This is, indeed, a ‘sense of community … not only as an administrative entity but something also spiritual, a territory where the human person rediscovers his own natural dimension and returns to relations based on affect rather than interest’.22 Padanian identity, Islamophobia and a sense of being a victimised minority strongly colour the militants’ own sense of togetherness – the left is often held to be both absent from communities, yet also culturally dominant.

Beyond this self-mythology, the Lega Nord’s activist base – rooted among small businessmen and independent professionals outside the biggest cities – certainly does have material interests.23 This is expressed both in a call for low taxes and the retreat of the central state, and the demand for its own heartland regions to keep more of their own tax revenues. In this sense, the Lega Nord put a special northern spin on the broader privatising and tax-cutting agenda advanced by the Pole of Freedoms coalition in the 1994 general election. This campaign, mounted together with Silvio Berlusconi, combined a classic neoliberal mix of the call to slim down what sociologist Pierre Bourdieu labelled the ‘left hand’ of the state – welfare, investment, public services – while also reinforcing its ‘right hand’, from law and order to subsidies for certain protected categories of business. This Pole of Freedoms alliance, standing in northern regions, stood separately from the so-called Pole of Good Government which Berlusconi sealed with the postfascist AN. Yet there were deep similarities, too: in each case an identitarian anti-communism was combined with a general offensive against partitocrazia and a confected ‘outsiderishness’.

The ability of this outwardly populist and anti-political agenda to extend beyond parochial identitarianism was most strikingly illustrated by the alliances the Lega built. This was first notable in the curious trajectory of Emma Bonino, in 1994 a supporter of the Pole of Freedoms. A well-known liberal, she in fact spent most of her political career in the secularist Partito Radicale, fighting for such causes as abortion and divorce rights and the legalisation of cannabis. Such were her centrist credentials that in 2006–8 she became foreign minister in an administration led by the Democratic Party, and in 2018 leader of the small European-federalist party +Europa. Yet back in 1994 Bonino instead stood as an independent on a Lega Nord list, as part of the broader right-wing alliance. This was something of an eccentric choice but also had a clear logic, explained by Bonino in an interview with Il Messaggero in the run-up to the election. She emphasised that, while she had strong differences of political identity with the hard-right party, her liberal, free-market politics shared much in common with the Lega Nord’s own call for a slimming of the Italian state:

Many things divide us from the Lega, but it’s also true that other things unite us, starting with [support for the] first-past-the-post electoral system. It’s no accident that [she and fellow Radicals] successfully promoted, together with the Lega, the campaign for thirteen anti-statist and anti-corporatist referendums … the vast majority of those who define themselves as progressives in reality embody a force for the conservation of the partitocrazia … [We and the Lega are united] by the common battle against the partitocrazia and the wasting of public funds.

In the generally volatile situation of the early 1990s, liberals and leghisti united in the name of a Thatcherite revolution in Italy. As Bonino mentioned, this included a series of referendums cosponsored by the Lega Nord and her own Radicali, from privatising public broadcaster RAI to banning trade unions from directly collecting dues from workers’ wages. Yet, if the campaign to finish off the First Republic was driven by actors spanning left–right divides, the alliances that emerged in 1994 were also liable to sudden and radical shifts. While upon its election Berlusconi’s coalition enjoyed a large majority in the Chamber of Deputies, it would not even last one year in government. Relations were soon strained by revelations of the tycoon’s collusion with the Sicilian Mafia and Calabrian ’Ndranghetà. Indeed, when news emerged that the media magnate faced fresh police investigations over his tax affairs, Bossi moved to split the coalition. But there was also a more strictly political reason behind the split: Berlusconi’s public repudiation of the Lega Nord’s plan to give the regions greater autonomy.

Bossi claimed that, in blocking this federalisation policy, concretised by the Lega Nord congress in November 1994, Berlusconi had reneged on his pre-election commitments to his allies. Yet in his bid to displace the tycoon’s administration, Bossi also operated a radical shift of his own – allying with figures equally opposed to his northern-autonomist agenda. His close collaborator here was PCI veteran Massimo d’Alema, a leading figure in the PDS, able to promise the centre-left’s votes for an alternative government. The two men’s meeting at Bossi’s little-used Rome address would rather bathetically be named the ‘pact of the sardines’ – an allusion to the sparse snacks that the Lega Nord leader was able to muster for his guests. It was nonetheless significant, as Bossi agreed to pull his party out of the Pole of Freedoms and join the PDS in backing an alternative administration led by former Bank of Italy director-general Lamberto Dini. This ‘technical’ government was appointed by president Eugenio Oscar Luigi Scalfaro in the name of piloting Italy toward a fresh general election, but it also had the task of ‘cleaning up the public finances’ – above all through a reform to cut the state’s pension bill.

Supporters of this deal to back Dini characterised it as a break in ‘political government’, instead inaugurating an administration which could impose reforms that stood above ordinary party divides. Such an arrangement had been premiered in April 1993, in the final months of the First Republic, when former Bank of Italy governor Carlo Azeglio Ciampi was appointed head of a majority-DC cabinet, in the first republican administration to be led by an unelected figure. In the Italian political system, no prime minister is directly elected, and indeed it was only through the rise of Berlusconi (and later Renzi) that this office assumed such a strong electoral-media role, more akin to a presidential system. But what was new in the technical cabinets headed by first Ciampi then Dini was that they each relied on personnel drawn from outside the electoral arena, lifted to office in the name of correcting the inefficiencies of democratic politics. Every minister in Dini’s cabinet was an unelected technocrat, and its base in parliament bore no reference to the coalitions that had stood in the 1994 general election.

The Dini government was also notable for enshrining a characteristic trait of the Second Republic, itself driven by Italy’s changed international position. This cabinet of technocrats was built on the consensus that decisions were needed to adapt the Italian public finances to the conditions of the European Economic and Monetary Union, even if no democratically elected party wanted to take direct responsibility for implementing them. For the hard-right Lega as for the ex-Communist PDS, the pursuit of certain policies – and in particular the need for so-called ‘balanced budgets’, with rock-bottom levels of public borrowing – now stood above normal democratic competition. Even Forza Italia abstained on confidence votes during the Dini administration, rather than try to block its work. In the period of the post-2008 economic crisis, these principles would again assert themselves in the technocratic cabinet led by former Goldman Sachs advisor Mario Monti from 2011 to 2013, as well as by the grand coalition that immediately followed it.

There was nothing incompatible between this logic and the Lega’s identitarian radicalism, which in fact hardened in the period of its break with Berlusconi. Within just years of its founding, the Lega Nord had become a key force in a national government, throwing its weight behind a tycoon and then a former central banker in order to further its aim of trimming the Italian state. But the parliamentary pact with the PDS had not amounted to a wholesale dissolution of left-right divides. When the early general election came in April 1996 the Lega Nord found itself standing outside of both the main electoral blocs – and the results were paradoxical. While the Lega’s overall vote share rose two points – to over 10 per cent of the national electorate – it was squeezed by the same first-past-the-post system that had powered its initial rise. Already in January 1995, Bossi’s ‘pact of the sardines’ had seen his party lose 40 of its 118 MPs, who remained loyal to Berlusconi’s Pole of Freedoms. With the 1996 general election, the Lega was reduced to just 59 seats in the Chamber of Deputies.

The Lega’s attempt to deal with these setbacks was defined less by a move to the right as by the sharper stance it now adopted against the central Italian state. Having repudiated the centre-right alliance and Berlusconi, Bossi pushed for a change in the party’s image, adopting an openly secessionist agenda. As the promise of reforming the Italian state waned, in 1997 Bossi renamed the party the ‘Lega Nord for the Independence of Padania’, insisting that this ‘country’ straddling the Po Valley from the Alps to the Adriatic should cast off the South altogether. Yet, if this secessionism marked a sharp break from the typical codes of republican politics, there were also elements of continuity with the agenda the Lega Nord had followed in backing Dini. With Italy widely expected to fail to meet the convergence criteria to join the euro upon its launch in 1999, Bossi insisted that the wealth-ier northern regions should not allow the South to drag them down: a new and independent Padania would, instead, be able to take its place in the concert of European nations.

There were certain tensions between the Lega Nord’s pro-business agenda and its folk nationalism – the radical-right party’s secessionism represented a clear destabilising force in Italian politics. Yet Bossi also sought to diversify the party’s image and make it more like the ‘nation’ it sought to rally. This was the impetus behind the unofficial Padanian Parliament it created in 1997, which would supposedly serve as the launchpad for a new state. In this cause, a series of Potemkin parties were organised, from the Padanian Communists (whose candidates included one M. Salvini), to a list aligned to Bonino’s Radicals, or the top-placed lists, respectively named European Democrats – Padanian Labour and Liberal Democrats. The Lega claimed that around six million people had participated in this vote – far beyond its own four million tally in the 1996 general election. The institution created by this election had no actual powers. Yet this also set a precedent by which the Lega Nord used unofficial referendums to mobilise its own base, a dress rehearsal designed to show that a Padanian state could, or even would, soon come into being.

In Government, against Rome

Yet Padanian secessionism brought major strategic problems, even in elections for regional councils – bodies with a wide array of powers over health care, education and transport, as well as an important platform for propaganda. And the Lega had no chance of securing absolute majorities in such councils without the aid of the wider, all-Italian centre-right parties. In the 1996 general election, the party had been isolated from both main political blocs, and the success of Romano Prodi’s centre-left government in bringing Italy into the euro in 1999 scotched even the notional possibility of Padania joining the single currency on its own. Bossi’s politics of slimming down the state and pushing privatisation were now the mainstream, but its pro-independence stance was minoritarian. It was thus caught between its ability to mobilise a radical minority, including in party activism, and its need to form broader alliances to win first-past-the-post contests. Hence, for all its rhetoric on the impossibility of reforming the Italian state, by the 1999 European elections the Lega Nord had turned back toward a pact with Forza Italia and the smaller right-wing parties. Just as the experience of 1994–96 had highlighted Berlusconi’s need to keep the Lega on the side, Bossi would, over the next two decades, repeatedly return to electoral pacts with his eternal brother enemy.

In the era bracketed by the war on terror and the financial crisis, the Lega Nord’s involvement in the Berlusconi governments of 2001–6 and 2008–11 would begin its conversion into a more conventionally hard-right force, indeed the tycoon’s strongest ally within the centre-right coalition. Even beyond the Bossi-Berlusconi connection, there were also specific areas of accord between the postfascists and the Lega. Having at least muted its commitment to destroy the Italian state, around the turn of the millennium, the northern chauvinist party increasingly took up the campaign against immigration. In 2001, Bossi buried the hatchet with AN’s Gianfranco Fini to co-author a bill that massively expanded the apparatus of migrant detention and expulsion. At the same time, in the bid to maintain an ersatz ‘outsiderishness’, Bossi increasingly resorted to shock communication tactics, for instance in his comments that the navy ought to fire on the boats of arriving refugees. This harsh identitarianism – expressed in the form of victimhood – was also put on display in election posters portraying a Native American with the tagline ‘They didn’t control immigration, now they live on reserves!’

The Lega Nord’s tonal divergence from the codes of republican institutions sat oddly with its actual presence in government. Clinging to their own territorial identity, Bossi’s activist base did not warm to Berlusconi or even to leghista officials serving in ‘the Rome government’ like interior minister Roberto Maroni. They could, at least, content themselves with the idea that the party represented a regionalist opposition within government ranks. This balancing of ‘Padanian’ and Italian commitments was most theatrically demonstrated by the Lega’s Luca Zaia, agriculture minister from 2008 to 2010, who led protests outside his own ministry in order to demand more funds for his home region. His insistence on more cash for wealthy Veneto would have made little sense for a genuinely national politician. Yet such bizarre antics also suited the leghista minister’s plans for what came next, serving as a kind of foreplay for his campaign to become president of this region. While the Lega Nord had no chance of securing regional government if it stood outside the centre-right alliance, the pact with Berlusconi allowed it to take Veneto for the first time in 2010, as well as the Piedmont region surrounding Turin.

Compared to the Forza Italia ministers chosen from among Berlusconi’s personal associates, Zaia and his colleagues were far more bound by the politics of their home regions as well as their accountability to party activists. This owed not only to the Lega’s regionalist identity but also the fact that its organisation was based on a mass of territorial branches. This accountability to local cadres – whose sources of funds and institutional weight also rose with breakthroughs in regional and mayoral elections – contrasted with the ‘light’ organisational form pioneered by Berlusconi, in which posts and influence remained under the tight control of the party’s owner-proprietor. Even amid the general volatility of the Second Republic, in which campaign vehicles like Forza Italia did away with ‘dense’ mass-party structures, Bossi’s Lega Nord was built on an organisational model more akin to its 1980s counterparts, sometimes even called a ‘Leninist’ model. Rallied in a force that had arisen in opposition to the First Republic, the leghisti nonetheless carried forth some of the assumptions of the previous era of political engagement. Indeed, already by the time of the 1996 general election the Lega Nord was the oldest party represented in the Italian Parliament.

If the 1990s saw widespread claims in the death of the mass-party form – exemplified by the wider collapse of the First Republic – the Lega Nord’s history instead highlights the merits of this more rooted model, allowing the party to endure even severe defeats. Its mass membership – hitting 112,000 by 1992 – was an impressive countertendency, especially considering that one could not simply sign up as a member of the Lega; rather, one had to earn membership through activism and attendance at meetings. This deep sense of ongoing party commitment, combined with the regionalist identity of which the Lega boasted under Bossi’s leadership, made it quite unlike the media machines with which it clashed each election time. As recent research on Lega membership structures has highlighted,24 its territorial roots are maintained not only through such practices as party gazebos (a way of maintaining direct contact with local populations) but also regular member meetings with elected officials as well as parallel and voluntary organisations representing such groups as women and youth.

As we shall see further on, today’s Lega is less rooted in local branches, or indeed ‘Padanian’ identity, than it was under Bossi’s leadership. From 2011, not long before Bossi was forced from office, to Salvini’s electoral breakthrough in 2018, the party’s number of territorial sections in fact fell by over two-thirds, from 1,451 to 437.25 Yet, through the volatile times of the Second Republic, these deeper structures had rendered the Lega Nord far hardier than its rivals, time and again proving able to renew itself notwithstanding the electoral setbacks that followed each spell in government. The party had not just ridden the ideological wave of ‘Bribesville’, with its revolt against the corrupt party system in Rome, but also, paradoxically, created a vehicle much more similar to the mass parties that Clean Hands had destroyed. This laid both the political and organisational bases for the Lega’s conquest of small towns across northern Italy, a bedrock that survived even Bossi’s own downfall.

The Revolution Eats Its Children

As we have seen, Bossi’s leadership of the Lega Nord was shaped by the tension between its regionalist and national ambitions. Throughout his period of control, and especially after the party’s first spell in national office in 1994, Bossi sought to present himself as a ‘guarantor’ figure, who would protect the interests of members against any corrupting effect that serving in the Rome government might have on ministers. The rise of a layer of leghista ministers, MPs, and European and regional/local representatives created what some activists derided as ‘the party of the blue cars’, supposedly focused on maintaining their own perks. From the very top of the organisational machine, Bossi could, in part at least, sidestep such an accusation. His only ministerial role in Berlusconi’s governments (‘Minister for Devolution’) was a purely propagandistic one, allowing him to keep one foot outside of the central Italian state and claim to represent the leghista base directly rather than the government as a whole. As his election posters put it: ‘further from Rome, closer to you’.

Whereas the Lega’s anti-corruption stance had soon brought Berlusconi’s first government to retreat and then collapse,26 the alliances of the 2000s were more governed by a tacit division of control. Here, Bossi’s party was allowed to lead the broader centre-right alliance in its heartlands in exchange for backing national-level legislation that shielded Berlusconi’s interests. Where, in 1994, the Lega had withdrawn its backing for the Biondi bill in the face of public pressure, over Berlusconi’s subsequent spells in office (2001–6 and then 2008–11), it instead gave its support to the billionaire tycoon’s ad personam legislation. This included backing for the infamous Gasparri bill, which protected Berlusconi’s media empire, or the measures known as Lodo Schifani and Lodo Alfano, to protect ministers from police investigation. When the Constitutional Court threatened to block this latter bill, Bossi said he was prepared to ‘lead the people in arms’ to ‘defend democracy’.27

The contradictions in the Lega’s anti-corruption agenda were not limited to its ties to Berlusconi – rather, they were also reflected in its own internal structures. Already in the Clean Hands years, Bossi had appeared in a dual guise, cheering on the magistrates before being called into the dock himself. But, while Bossi’s admission of illicit funding from the Montedison industrial group had seen him escape with a suspended sentence – sparing the Lega any immediate political fall out – his own opaque control made party funds increasingly inscrutable. When Bossi suffered a stroke in 2004 (forcing him to miss the Pontida rally, which was, in turn, cancelled), he opted not to begin a succession process, but rather to centralise his authority against potential rivals for the leadership. The ‘magic circle’ of party insiders organised by his wife excluded even figures like Interior Minister Maroni and began treating the party as well as its finances like family property. Though Bossi purported to play an executive role in the Lega, allowing him to discipline the ministers in Rome, in fact he was unaccountable to the base.

The end of Berlusconi’s last government in autumn 2011, which again pushed the Lega into opposition, was soon followed by the final explosion of this set-up. On 8 January 2012, Il Secolo XIX newspaper broke the news that Lega Nord treasurer Francesco Belsito, a Bossi appointee, had illicitly drawn on state funds from Cyprus and Tanzania, using the cash to provide personal favours to fellow members of the ‘magic circle’. Three days later, the scandal intensified as Bossi voted to shield from prosecution Nicola Cosentino, an MP from Berlusconi’s party who had been arrested for his alleged ties to the Naples mafia. The combination of internal impropriety and support for Berlusconi finally provoked a revolt in the leghista base, who called on Maroni to take action to reclaim the party. Bossi went on the counteroffensive, cancelling all public meetings involving the former interior minister. Nine days later, a protest against Mario Monti’s centrist government instead became the scene of an open clash between followers of these rival Lega leaders.

Revelations into the Lega’s dubious financial practices followed thick and fast, highlighting the webs of corruption and ties to organised crime that had built up under Bossi’s leadership. Indeed, it was a case starkly reminiscent of those that had felled the parties of the First Republic. The regional government in Lombardy – a key leghista heartland – itself came under investigation for ties to ’Ndrangheta, the Calabrian Mafia, and by early April, the leadership crisis had become unmanageable. As the prosecutors closed in, Bossi was forced to abandon the role he had held for over two decades. Amid a string of resignations, Maroni became new party secretary, promising a clean-up operation in Lega Nord ranks as well as a bid to assume the same powers that Bossi had enjoyed, maintaining its hierarchical structure. Yet it was a young cadre in the affections of both men – Matteo Salvini – who took over the leadership of the Lega Lombarda, vowing to shake off the figures who had dragged its name through the mud.

This was not the end of the Lega Nord’s crisis – indeed, in the February 2013 general election, it hit a fresh low. Even faced with Mario Monti’s unpopular technocratic government, supported by both the Democrats and Forza Italia, the Lega was unable to turn attention away from its own internal woes. Having lost two-thirds of its members since 2010, the Lega Nord took just 4.3 per cent of the vote, or half its 2008 score. This was, in political terms, a historic nadir. Back in 2001, the Lega Nord had shed even more votes after its series of U-turns on the independence question. Yet then it had been saved by the wider context of right-wing advance, allowing it again to play a kingmaker role in forming the subsequent centre-right government. The 2013 defeat offered no such consolation, as the Lega slumped into near-irrelevance while the M5S soared to first place. The message that ‘the politicians in Rome’ were all the same was now being championed by a newer force – and directed against the Lega itself.

Two decades after the corrupt PSI man Mario Chiesa’s bid to flush his payload, the forces that had broken up the First Republic were being eaten by their own revolution. The accusations even struck at Antonio di Pietro, the protagonist of Clean Hands and leader of the small centre-left party Italia dei Valori (Italy of Values; IdV). On 28 October 2012, he was targeted by RAI’s Report, an investigative current affairs programme that emerged during the wave of judicial populism. Di Pietro was accused of keeping €50 million of electoral expenses under own family’s control, while building up a real-estate empire supposedly including fifty-six properties. Faced with scandalised editorials, Di Pietro strongly denied the allegations of impropriety and even brought a successful libel action against the producers. But, as he put it immediately after the accusations were aired, IdV had ‘died on Sunday night’s Report’. The new era in Italian public life had personalised everything – and for someone who claimed to stand only for anti-corruption, it was political death to see one’s claim to clean hands tarnished.