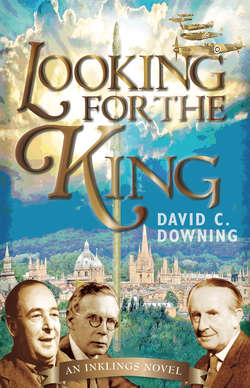

Читать книгу Looking for the King - David C. Downing - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2 OxfordLate April

ОглавлениеTom surveyed the labyrinthine aisles of books, stacked floor to ceiling, with neatly hand-lettered signs pointing to more books by the thousands on the floor above. He could have stopped to ask one of the clerks in Blackwells, Oxford’s most well-stocked bookstore, where to find studies of medieval literature. But he preferred to wander the maze on his own, making a passing acquaintance with Greek philosophers, Persian poets, and British military historians until he sensed he was somewhere in the right neighborhood. He spotted Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress on a high shelf, so he figured his own pilgrimage must be progressing satisfactorily. Knowing he had to travel back another four centuries or so, and then find the commentators, he eventually located the book he had been searching for, The Allegory of Love by C. S. Lewis. Though the book had only been published a few years earlier, it had already become required reading for graduate students in America.

Tom reached out for the book, and almost bumped elbows with someone else trying to take a book off the same shelf. “Pardon me,” he said reflexively, turning to see a young woman with searching eyes and dark curly hair. “I didn’t see you there.” She offered a polite smile, revealing dimples that offset those serious eyes. “Sorry, I didn’t see you either,” she said, her accent revealing that she was another American. They both extended their arms again, but this time their hands touched. They were reaching for the same book. The young woman laughed a bit nervously. “I guess we’re after the same item,” she said.

“I saw it first!” Tom said, only half-jokingly. He really wanted to have a look at this book.

“I can tell already you’re an American,” the young woman said. “No manners. Haven’t you ever heard the principle, ‘Ladies first’?” Her tone was also light, but Tom was no great reader of women, and he wasn’t sure how serious she was being. He made a mock chivalric bow, and replied, “Ordinarily, that is my life’s creed. But I do have a special reason for wanting to look at this book right now. I’m meeting its author for lunch in half an hour.” Tom was afraid this sounded too much like boasting, but he wasn’t it making up. He really was going to meet the Magdalen don for lunch at the Turf Tavern at one o’clock. That’s why he wanted to peruse the book. For one thing, he was hoping to find out what “C. S.” stood for prior to meeting the man behind the initials.

“Well, aren’t I impressed!” the young woman answered.

“Any other books here by friends of yours?”

“No, really!” Tom insisted. “When I was working on my master’s thesis, I wrote Professor Lewis about some of his references to Camelot. He wrote me back and invited me to meet him for lunch if I were ever in Oxford. So I called him up as soon as I arrived here last week, and arranged to meet him for lunch today at the Turf.” Tom realized he was explaining more than he needed to, recalling as well his tendency to babble when flustered.

The young woman took the book off the shelf and handed it to Tom. Then she made a sweeping curtsey, every bit as courtly as Tom’s sweeping bow a moment before. “I yield to the greater claim,” she said. “I was merely seeking knowledge.”

Tom really did want to review the book before heading over to the Turf, but he wasn’t exactly in a hurry to end this conversation. “I don’t claim to be an expert,” he said. “But if you have a particular question, maybe there is something I could help you with.”

At this, the young lady turned slightly pink and she interlaced her fingers. “It’s actually something personal. Just something I’m trying to figure out.”

“That’s all right, I understand,” answered Tom, even though he didn’t. She was looking for personal answers in a book on medieval allegory? The silence hung heavy in the air between them, so Tom continued. “Thanks for allowing me to peruse the book. I’m not going to carry it off. You can have it back in a few minutes.” She looked up and nodded, and he decided to forge ahead. “By the way, my name’s Tom. Tom McCord. From California.” He reached out his hand, and she shook it, exactly one shake. She had soft fingers.

“Laura,” she said. “Laura Hartman. From Pennsylvania.” They both smiled, and Tom added limply, “Pleased to meet you.”

“Listen,” said Laura, “if you are going to do some lastminute cramming before meeting the author, you’d better get to it.” She tapped on the book for emphasis and turned to go. As she stepped away, she called over her shoulder, with a hint of mischief in her voice, “You should probably know: your pen pal has written an allegory of his own, not to mention a science fiction novel.” Tom raised his hand, as if wanting to ask a question in class, but she kept on walking till she turned a corner and went out of sight.

Tom looked down at the book in his hands. He still wanted to give it a quick review, but what he looked at just now was the exact spot where she had tapped its cover. He glanced back at the vacant aisle, then turned to the book and began reviewing its pages. After a few minutes, he checked his watch, put the book back in its place, and headed toward the entrance of the bookstore. Near the front, he stopped at the clerk’s desk, but the bespectacled young man sitting on a stool there seemed entirely absorbed in his copy of The Future of an Illusion.

Tom stood at the counter for as long as his patience would allow and then said, “Excuse me.”

“Just one moment,” answered the clerk without glancing up from the page. Finally, he turned a page, dog-eared its corner, and looked up. “Yes, what is it?” he asked brusquely, as if he’d just been interrupted in the middle of a meal.

“I’m wondering what books by C. S. Lewis you have in stock,” said Tom.

“I’d have to go check,” answered the young man.

“Could you please?”

“The young man sighed, put down his book, and turned to look at a small card catalog.

“From Feathers to Iron,” he intoned. “A Time to Dance and other Poems.”

“What about The Allegory of Love?” asked Tom.

“Allegory of Love?” said the young man quizzically. That’s by that other Lewis, the Christian, not the Communist.”

“Yes, C. S. Lewis,” explained Tom, trying to keep the exasperation out of his voice.

“I thought you said, ‘C. Day Lewis,’” explained the young man curtly. “I haven’t quite developed an ear for the American drawl.” He flipped back a few cards and then found what he was looking for. “Yes, here it is. C. S. Lewis. Allegory of Love. Literary criticism. That’s near the back on the left, aisle seven, I believe.”

“Yes, it is,” said Tom. “I was just back there looking at it. I wanted to know about other titles by C. S. Lewis.”

The young man gave a little shrug, as if to say there was no pleasing certain customers. Then he read off several more titles. “Dymer. A narrative poem. Out of the Silent Planet. Fantasy. The Personal Heresy. Literary criticism. The Pilgrim’s Regress. Christian allegory. Rehabilitations …”

“That’s fine,” said Tom. “I get the idea. The man sounds positively prolific. I wonder if he has any time left over for teaching.”

“You’re not a student here, I assume?” asked the young clerk.

“No, just visiting from America. Why do you ask?”

“Actually, C. S. Lewis is more well-known around here as a lecturer than as an author. Quite possibly the most popular speaker in Oxford. Even when he lectures on a Saturday morning, about some seventeenth-century poet no one has ever heard of, the hall will be packed, with people perched on windowsills.”

“Maybe they come to hear the man who’s written all those books?” Tom wondered aloud.

“Not likely,” sniffed the young clerk. “He’s earned his place among the literary critics. But science fiction novels? Christian allegory? A popularizer and a proselytizer. It’s such wretched bad taste. How could one of the most promising scholars of his generation turn out to be a bullyragging Bible-thumper?”

“Good question,” said Tom. “I’m having lunch with Professor Lewis right now, and I’ll ask him.” With that, Tom turned on his heels and headed for the front door. He didn’t look back to take in the clerk’s expression. He preferred his own mental picture, a young man with mouth agape and eyes wide behind those spectacles, his face a mixture of surprise, wonder, and probably envy.

Tom pushed open the door and went out onto Broad Street, enjoying not only his well-staged exit, but also the crystalline April sky above and classic elegance of the Sheldonian Theater, just across the street. Stepping briskly through traffic of bicycles and black sedans, Tom crossed over to the Clarendon Building, originally the home of Oxford University Press. He looked up momentarily as he walked by. There were nine gigantic lead statues posted around the rim of its roof, each representing one of the muses. Rumor had it that some of them were coming loose from their base, so passersby had developed a habit of glancing up, just in case one of the immortal sisters chose that moment to come crashing to earth like a Luftwaffe bomb.

Tom continued east down Broad Street, crossed Catte Street, “street of the mouse catchers,” and continued on to Holywell. Taking a right at Bath Place, which seemed hardly more than an alley, Tom wondered if he made a wrong turn when the lane ended abruptly after half a block. But then he saw a low door there, framed in black timbers, and the words “Turf Tavern” half hidden behind a burst of blossoms from hanging flowerboxes. Tom stepped inside and found a low-ceilinged room with rough-hewn rock walls and a scuffed wooden floor. He had no trouble believing that this was the oldest pub in Oxford, going back to Chaucer’s time. It was full of young people, though, mostly fashionably dressed men with pomaded hair.

Tom scanned the crowded room until he saw a slender, silver-haired gentleman sitting alone at a table, reading a leather-bound book. He made his way over to the table and asked diffidently, “Excuse me. Professor Lewis?” The older man looked up with momentary bewilderment, then pointed without a word to a back corner of the room. Tom looked over and saw another man sitting alone, a portly, ruddy-cheeked man with thinning hair, wrinkled baggy pants and an ill-fitting coat. He looked more like a country farmer who’d stopped in for a ploughman’s lunch than a celebrated man of letters. Tom glanced down again at the distinguished-looking gentleman to see if there was some mistake, but the other man just offered a thin-lipped smile and nodded his head in confirmation.

Tom worked his way past several more tables and approached the second man, who was holding a book called Diary of an Old Soul in one hand and a pint of cider in the other. “Excuse me. Professor Lewis?” he tried again. “Yes, yes,” said the other genially, rising to shake hands. “And you must be McCord,” he added in a deep resonant voice, gesturing at the empty chair across the table. Tom took a seat, stared across the table at that round, friendly face, the broad forehead and the big, liquid eyes. Suddenly Tom discovered that he had completely forgotten how to make words come out of his mouth.

“So, you’ve come over from America, I understand?” said Lewis.

All the words in the English language suddenly vied for Tom’s tongue, and he wanted to say, “California” and “research grant” and “Arthurian romance” and “great admirer of your work” all at once. Finally, he mustered all his verbal powers and answered, “Yes, that’s right.” He paused for several seconds, until subjects and verbs started finding each other in his brain, and then he continued: “I’m over here working on a book. I don’t know if you recall my letter, but I did my master’s thesis on Arthurian literature and now I’m doing some follow-up research.”

“Yes,” answered Lewis, “I recall the letter. Reality and romance. From history to legend to literature. That sort of thing. I think I recommended Collingwood? And perhaps Tolkien’s essay on Beowulf?

“Yes, sir. Both very helpful. I’m over here visiting the traditional Arthur sites. I’m looking for evidence of actual historical figure, a Romanized Celt who kept the Saxons out of the west country.”

The two men ordered lunch, a plate of fish and chips for each, with a pint of bitter for Tom and another cider for Lewis. Lewis briefly bowed his head before taking a bite, then returned to their topic: “So you’ve been studying King Arthur at university, have you?”

“Yes, sir. I just finished my master’s at UCLA.”

Lewis had a puzzled look, so Tom went on: “That’s the University of California. In Los Angeles.”

“Ah,” said Lewis, with a sudden look of recognition. “California. Where they have all the sunshine.”

Tom nodded.

“I’m more of a polar bear myself. I prefer a fine winter’s day to the blaze of summer.”

“In the States, people move clear across the country for our balmy skies,” said Tom.

Lewis pondered this a moment. “I wouldn’t think of moving somewhere just for the climate,” he said. “Unless I were a vegetable. Before I moved house to a new city, I’d want to know about the sort of people I’d meet there. And the beauty of the landscape.”

“You’d get conflicting opinions on both those topics about California,” said Tom. “I grew up in a little town called Ventura. I just went to UCLA because it was fairly close to home.”

“And what subjects did you choose for your examinations?” asked Lewis.

“Well,” explained Tom, “we don’t do things the same way over in the States as you do here. Instead of tutoring and comprehensive exams, we sign up for several classes every semester. Each time you earn a passing grade in a course, you are awarded credits. Then once you’ve accumulated enough credits, you earn a bachelor’s degree.”

“Oh, yes, that’s right,” said Lewis, nibbling on piece of fried haddock. “I believe I’ve had that explained to me before. I don’t think it’s a system that would suit me. It sounds like someone judging a horse not by its speed or strength, but by how many oats you’ve tried to feed it.”

Tom grinned at the analogy. “Yes, that’s about how it feels from the horse’s point of view as well.”

“And what about the master’s degree?” asked Lewis. “More provender?”

“Well, more coursework. But I did write a master’s thesis. I called it Arthur through the Ages.’ Nothing terribly original. Just an overview of what you might call the many layers of Arthurian legend.”

Lewis kept eating and kept listening, so Tom assumed he wanted to hear more: “At the bottom layer, a Celtic commander who kept the Saxons at bay. Then the Welsh bards and chroniclers, turning Arthur into a world conqueror and adding the wizard Merlin to his retinue. Then the French romancers, less interested in the knights as warriors than as lovers. Lancelot moves to center stage, his adventures involving less armor and more amour, you might say.”

Tom paused, hoping to detect an appreciative smile on Lewis’s face. But the older man just kept eating, so Tom continued: “Finally, the Grail quest stories and the newest character, Galahad the Good.”

“Yes, it’s true,” said Lewis, finishing off a chip and licking his fingers, again reminding Tom more of a country farmer than an Oxford don. “Even in a fairly late version like Malory’s, you can see Christian characters like Arthur and Galahad, mixing with the almost druidical Merlin. It looks like Britain in that twilight era between the Romans and Saxons. For me, Arthurian tradition is less like layers, and more like a cathedral—the work of many hands over many generations.”

Not waiting for the inevitable question, Tom decided to explain: “I’m over here working on a book, a guide for visitors who want to visit the most famous Arthurian sites for themselves.” Lewis looked up quizzically, and Tom thought he saw another inevitable question coming. “I suppose you must think I’m nuts—uh, daft, I guess you would say—for coming over here to research a book when there’s a war on.”

“On the contrary,” said Lewis, “I quite understand. And I approve. War does not create fundamentally new conditions. It simply underscores the permanent human condition. There is really no such thing as ‘normal life.’ If you’d actually lived in past eras that we think of as settled and peaceful, I’m sure you would find, upon a closer look, that they were full of crises, alarms, conflicts, and tribulations. Civilization has always existed on the edge of a precipice.”

Lewis took a sip of cider and continued: “Besides, it’s just human nature. War, terrible as it is, is not an infinite thing. It cannot absorb the full attention of the human soul. Soldiers read novels in the trenches. Old men propound new mathematical theories in besieged cities. Just a few months ago, I saw a student of mine right here in Oxford with a brightly colored hawk tethered to his wrist. Here is a young man who could be called into the army any day now. And yet his whole mind is focused on reviving the ancient art of falconry. I say, Blessings upon his head!”

“I wish you’d been there when I was trying to explain this trip to my father!” exclaimed Tom. “But a moment ago,” he continued, “when I brought up my research over here, I thought I saw a skeptical look on your face.”

“Oh, that wasn’t about the war,” answered Lewis. “I just wondered if you’d found what you were looking for. For me, the enchantment of the old romances lies in the literary artistry, not the local geography.”

“I’m not sure I understand,” said Tom.

“When I was about your age, I took a trip down to Tintagel—magical name!—where the old books say Arthur was born. The fierce waves tumbling against the rocky coast and the crumbling castle on the edge of a cliff were worthy of Layamon or Malory. But the old tin mines that scarred the landscape. The derelict farms with broken walls and gates off their hinges. Worst of all, right there by ‘Merlin’s Cave,’ as they call it, some blackguard, cursed by all the muses, has built a monstrosity called the King Arthur Hotel! It has cement walls, stamped to look like stonework, covered with an absurd miscellany of armor—a Highland shield next to a faux medieval breastplate, jostled by a helmet from Cromwell’s time. And right there in the main lounge you will find THE Round Table, of course, complete with all the knights’ names embossed in their proper places!”

“Yes, I have seen some of that,” answered Tom. “I suppose it is inevitable wherever there’s a dollar—or a quid—to be made. But it can work the other way too. When I was down at Cadbury—really, it’s just a tall green mound ringed with ancient earthworks. But in my mind’s eye, I could see a stout timber palisade on the hilltop, a great gate swinging open, two hundred horsemen, with leather helmets and crosses on their shields, galloping out to fall upon a Saxon host. For me, the actual site didn’t betray my imagination. Rather the place was transfigured by it.”

“Yes, yes,” I know exactly what you mean,” said Lewis, speaking for the first time with unfeigned enthusiasm. “When I was growing up, my family went on holiday to the Wicklow Mountains in the south of Ireland. As my brother and I were cycling around, the whole landscape seemed to me like something right out of Wagner. The entire time we were there, I kept expecting to see the fair Sieglinde just around the hill. Or I’d peer down into a crevice and wonder if I might see Fafnir the dragon guarding his horde. I loved nature for what it reminded me of before I learned to love it for itself.”

Tom nodded in agreement. In that moment, they were not a distinguished, middle-aged professor and an eager young American sharing lunch in a pub. They were two men who knew exactly what the other was talking about. Tom leaned in a little and said, “Can I tell you something? When I was down in Cornwall, I also went to Bodmin Moor, to Dozmary Pool.”

“Ah,” said Lewis, “the Lady of the Lake. Where Arthur received Excalibur.”

“And where Sir Bedivere returned it, on Arthur’s strictest orders, as the king lay dying. Well, Dozmary is just a round pond on a flat heath, surrounded by reeds. You could almost throw a stone across it. I’m sure there are twenty lovelier scenes within an hour’s hike of the pool. But there is something eerie about the place, knowing what they say about it. I stood there on the edge, looking at slate-gray water under a leaden sky. And I just couldn’t help myself. I found a dead branch, about three feet long, and I heaved it into the pool, just to see what would happen. I couldn’t help but think of those lines:

“So flash’d and fell the brand Excalibur;

But ere he dipped the surface, rose an arm

Clothed in white samite, mystic, wonderful …”

To Tom’s surprise, Lewis took up the verse, in his deep, booming voice:

“And caught him by the hilt and brandish’d him

Three times, and drew him under in the mere.”

The two men looked at each other in a shock of mutual recognition. “You know Tennyson!” said Tom. “Idylls of the King. I’m afraid he’s fallen badly out of fashion.”

“Oh, I have a pathological aversion to what is fashionable,” explained Lewis. “I think the poetry they publish nowadays will be known to literary historians as the ‘Whining and Mumbling Period.’”

“And yet,” said Tom, looking down at his plate, “I suppose it would be a kind of compliment if later generations took any notice of you at all.”

Lewis cocked his head slightly and kept listening, so Tom tried to explain: “I was in Blackwells this morning, all those rows and rows of books—including several of yours. I have to wonder what it would feel like to visit there again someday and see a handsome book on the shelf with my name on the spine.”

Lewis smiled and nodded that he understood. “Oh, yes, that,” he said, “‘The House of Fame.’ When I was your age, I positively ached to take my place on Parnassus. I spent most of my twenties working on a book-length poem that I hoped would put me in the company of Wordsworth, Tennyson, and Yeats.”

“What happened?” asked Tom, leaning forward.

“The worst possible fate!” answered Lewis, laughing to himself. “The poem was finally published, and no one took any notice!”

“I would think that would just fuel your ambitions,” said Tom. “To try and write another book in hopes that, like Byron, you might wake up one day to find yourself famous.”

Lewis laughed again with his great hearty laugh. “I suppose that was my first response,” he confessed. “But when I became a Christian a few years later, all that seemed to change. I ceased to want to be original, and just to do the best work I could. As for getting published, I think you’ll be surprised when your book comes out, as I have no doubt it will.”

Tom wasn’t sure he understood, so he just kept listening.

“There’s an itch to see your name in print,” continued Lewis. “You can hardly think of anything else. But once the book is published, you’ve scratched that itch and you find that nothing much has changed. The simple absence of an itch is not usually ranked among life’s great pleasures.”

Tom thought about this as he sampled a bite of mushy peas, and quickly washed them down with a swallow of beer. “I’ll have to take your word for it,” he said, “until I see my book in print—if that day ever comes.” He paused a moment and then added. “Professor Lewis, can you think of any reason some Englishmen might resent this project of mine?”

“I’m not sure what you mean,” said Lewis. “Perhaps they think Americans should be over here helping us fight the Nazis, not writing books.”

“Yes, that topic did come up,” said Tom with a nod. “But there was something more. I was accosted by two louts down in Somerset. They seemed convinced that I was up to no good, that I had something more in mind than just looking for the historical Arthur.”

“I wouldn’t know about that,” answered Lewis. He looked straight into Tom’s eyes, then leaned in and spoke barely above a whisper: “I do believe, though, that beyond our history, in the usual sense of the word, is another kind of history. A sort of ‘haunting,’ you might call it.”

Tom leaned in, as if willing to hear more of the secret, and Lewis continued: “Behind the Arthurian story may be some true history, but not the kind you have in mind. Throughout the English past, there seems to be something else trying to break through—as it almost did in Arthur’s time. Something called ‘Britain’ seems forever haunted by something you might call ‘Logres.’”

“Logres?” asked Tom. “The Welsh word for England?”

“Well, yes, that,” said Lewis, “but also more than that. Look it up in Christian poets like Spenser or Milton and see if it doesn’t mean something more. Or better yet, have a look at Charles Williams’s new book of poems, Taliessen through Logres. I think you’ll see what I mean.”

“Actually, I did pick up that book once,” said Tom. “To be honest, I couldn’t make heads or tails of it.”

Lewis nodded ruefully. “Yes, poor Charles. He’s a friend of mine. He’s always been plagued by the problem of obscurity.” Lewis looked like he was about to launch into an extended explication, but then he had a better thought. “Say, you’re in luck—or ‘holy luck,’ as Charles would call it. He’s right here in Oxford lecturing this term. You should go hear him speak and ask him yourself what he means by his books.”

“Is he a colleague of yours at Magdalen?” asked Tom.

Lewis leaned back slightly. “Here in Oxford, we pronounce it ‘Maudlin,’” he explained. “And, no, he’s not at any of the colleges. He’s an editor at Oxford University Press. Their London office relocated here when the war started last September. He’s a brilliant man, an autodidact—writes poetry, plays, novels, biographies, histories, even theology.” Lewis paused, then added a surprisingly soulful note: “He’s a great man. I’m proud to call him my friend.”

“I will most certainly make a point to read his books and attend his lectures while I’m in Oxford,” said Tom. “If for nothing else, to find out the secret of Logres.”

Lewis grinned and asked, “And how long to you plan to be here?”

“I’m not sure. A few months, I expect. I’ll be using Oxford as my home base, making forays out to some Arthurian sites.”

“Say, I have another idea,” said Lewis. “Williams, Tolkien and I have a little band of brothers that meets here in Oxford, Tuesday mornings at the Eagle and Child, just for talk. Would you like me to ask the others if you might join us?”

“I’m honored that you would ask,” said Tom. “I had hoped to meet Professor Tolkien while I was here.” But then he added, rather diffidently, “But I’m not sure. I’m just an untutored colonial. I wonder how well I would fit in with a clique of Oxford dons, sipping sherry and discussing ‘The Meaning of Meaning.’”

Lewis burst out laughing, in a deep, hearty guffaw. “Now I know you ought to come!” he said. “It’s not like that at all. We gather in the back parlor of the ‘Bird and Baby,’ as we call it, for some frothy ale and frothier talk. It’s quite a lively group, lots of laughter. People in the front room think we must be talking ribaldry, when we’re really arguing theology! And we love to skewer those linguistic birds who write books like The Meaning of Meaning!”

Tom smiled and agreed that he would like to come, if the others consented. They continued to talk for more than an hour, more like old friends than two men who had only met that day. Throughout the conversation, Tom had an odd sensation: instead of feeling smaller in the presence of this brilliant man, he somehow felt himself more intellectually keen than usual. It was odd how Lewis’s enthusiasm and learned repartee didn’t make Tom feel overshadowed. Rather he felt he shined all the brighter himself.

As the time came for them to leave, the two men stood and walked toward the door of the tavern. At their parting, Tom began feeling more formal again. “Well, Professor Lewis, may I say what a privilege it has been talking to you. I don’t know if I got my questions answered, but I’m sure this lunch will be one of the highlights of my trip to England.”

“You don’t need to call me professor,” said Lewis. As they shook hands, he added, “And don’t worry too much about those unanswered questions. Perhaps our lunch of fish and chips today was part of that other kind of history I was talking about before.”

As Lewis smiled and turned to leave, Tom pondered that last remark. He realized he’d just acquired one more question.