Читать книгу A Hunter's Confession - David Carpenter O. - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPREFACE

I HAVE TWO reasons for writing this book. The first is personal. A friend of mine from Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, a poet named Robert Currie, has been campaigning for many years for me to write a memoir. In this cause, he has been more persistent than a brigade of telemarketers. Every time I let down my guard, he would leap out from behind a bush or a dumpster and pummel me with the same entreaty. “Carpenter, you should really write a memoir.” “I’m too young, Currie,” I used to say. Or, once older, “I’m too busy, Currie.” Or, “Currie, why don’t you write a bloody memoir?” So I’m writing this memoir to get Currie off my back.

The second reason goes back to an incident that happened to me in 1995, which I have recounted in some detail in an earlier book entitled Courting Saskatchewan. In my account of this incident, which occurred up in the bush, I wrote about goose-hunting rituals in Saskatchewan. Some years later, my publisher, Rob Sanders (himself a former hunter), suggested that I write a longer book entirely about hunting—its culture, its history, its adherents and detractors, its rise and fall as a form of recreation and as a means of subsistence—a book in which these subjects might be shaped, to some extent, from my own experiences of hunting. That original incident that I had up in the bush is recounted once again, but in much less detail. It seems that I could not write A Hunter’s Confession without reflecting upon the incident that triggered it.

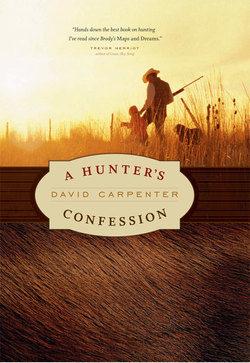

This book is filled from beginning to end with hunting stories, primarily from the United States and Canada. It recounts many a hunt from my own life and many stories from the lives of hunters mightier than I. I have written down the reasons I loved hunting, the reasons I defend it, and the reasons I criticize it. More than a memoir, then, A Hunter’s Confession is a serious book about hunting in North America. I cannot help but notice a curious congruence between my experience of hunting and the trends we see among hunters all over this continent.

But it’s still a memoir. If I appear to show a preference for the less than competent side of my adventures and spend little time on my prowess as a nimrod, it’s largely because I’ve known the real thing: hunters who know what they’re doing in the field and whose intimacy with the habitat and the animals themselves has turned into a great abiding love for and fascination with these creatures.

If you’re still with me, but skeptical, you might be wondering, If these guys love the animals as they claim, why do they kill them? I might not answer this question to your satisfaction, but I promise that, as the story unfolds, I will never wander too far from it. I would like to come out of this process with a good answer for myself. Therefore I have enlisted a great variety of writers, hunters, writer/hunters, and thinkers from the past century to give me some perspective on the rise and fall of hunting in my life and theirs. Hunting, like boxing, has attracted more than its share of eminent hacks, Nobel Laureates, and Pulitzer Prize winners.

Doug Elsasser, Peter Nash, Scott Smith, Terry Myles, Richard Ford, Ian Pitfield, Al Purkess, Raymond Carver, Lennie Hollander, Bill Robertson, Ken Bindle, Bonace Korchinsky, Mosey Walcott, Bill Watson, Bob Calder— these are some of the hunters I have known. Any one of them could have testified to my conduct in the field. Most of them would say that Carpenter was better with a shotgun than with a rifle; that he was a better dog than a marksman; that he started losing it in his late forties; that his sense of direction depended on whether he was carrying a compass, and even then it wasn’t that great; that he was loath to try a long shot and timid around bulls; that as walkers go, he was not bad for distance.

Readers can be grateful, then, that this is not so much about me as about the hunt. If I accomplish only one thing in this account, I hope it will be to narrow the gap between those who did and those who didn’t, between those who speak well of hunters and those who disapprove of them. You might say that I have one boot in the hunter’s camp and a Birkenstock in the camp of the nonbeliever.

For the idea and for your patience, Rob, I thank you. I hope you will agree that late is better than never.

And Currie, I am happy to say that your campaign has borne fruit. By the way, I think it would be a great idea if you were to write a book-length verse epistle on accounting practices in ancient Carthage. Better get started. Time waits for no man.

I am indebted to many people whose reflections on hunting have broadened my own knowledge considerably. Most of these have been mentioned in the text and in the list of sources at the end of the book. But I should add the names of those who helped to steer me into good habitat in order to write this book: Warren Cariou, Tim Lilburn, and Bob Calder, who are all either nonhunters or ex-hunters. I would like to thank Trevor Herriot for reading my manuscript and offering suggestions and criticism during a very busy time in his own life. I owe a debt of thanks to Honor Kever, my first reader and soulsustainer. I must thank my editor, Nancy Flight, who rode this project through three very different drafts and whose words guided me into my strengths as a writer and away from my weaknesses. I would also like to thank the Saskatchewan Writers/Artists Colony Committee of the Saskatchewan Writers’ Guild for the chance to work on this manuscript during the winters of 2007, 2008, and 2009. Our hosts were Abbot Peter Novekosky and Father Demetrius and the hospitable monks of St. Peter’s Abbey, nonhunters every one. I owe a big thank-you to Kathy Sinclair, whose advice, erudition, criticism, and forbearance kept the fire going, and to my eagle-eyed copy editor, Iva Cheung. And a final thank-you to Doug Elsasser for his woodsy wisdom and for his patience with me as perpetual apprentice in the finer points of hunting.