Читать книгу Angel on a Leash - David Frei - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеI Get It

Dogs are spontaneous. They live in the moment. They react to anything and everything that we say or do. They live, love, celebrate, and mourn with us whenever we give them the chance.

Interact with a dog—pet him, talk to him, feed him a cookie, go for a walk with him—and you feel better. Dog owners have known that intuitively for years; it’s a concept that anyone who has a dog understands. It’s the dog greeting you at the door, tail wagging at full speed, after you’ve had a long, tough day at the office. It’s the dog sitting next to you on the couch, putting his head on your lap when you need a little something.

It’s unconditional love. Your dog doesn’t care about appearances or how much money you make or how you talk. He just loves you, and he loves you every waking moment, whether or not you have good shoes.

It’s the combination of that spontaneity and the unconditional love that they give us every day that makes dogs so good at therapy work. No expectations, no grudges, no charge for the service. Well, maybe a good scratch right there … thank you very much.

I’ve been seeing this spontaneity and unconditional love happening with my dogs for a lot of years. In fact, I saw these things before I ever got serious about therapy dogs, but I just never really put it all together.

And here is how we know that it works: when a dog walks into the room, the energy changes.

The dog doesn’t need to be a high-profile show dog like Westminster Best in Show winners Uno, Rufus, or James, or a TV star like Lassie or Frasier’s Eddie. And the place doesn’t need to be a hospital or a nursing home. Any dog can make this happen, and it can happen anywhere. Sure, we see wonderful pictures of dogs visiting children, spending time with seniors, or comforting wounded military members in health care facilities. But it can happen for your elderly neighbor who lives alone, for someone you meet walking down the street, or right in your own living room just for you.

Maybe it’s the anticipation of that spontaneity or that unconditional love. Look! It’s a dog! Look at that haircut, look how excited he is to be here, look at his tail … wow! I want to pet him!

Suddenly, someone is thinking about something other than his or her challenges or pain or a grim outlook or the next treatment. Right now, for this moment, it’s not about the person, it’s about the dog.

Next, maybe it manifests itself in a smile—a smile from someone who hasn’t had much to smile about. I can’t tell you how often a parent has said to me as his or her child is petting or hugging or watching my dog: “That’s the first time she’s smiled this week.”

Maybe it’s a laugh or a few words or a step out of a stroller or wheelchair. Maybe it’s a lucid moment for someone, a look back in time at his or her own dog. It could be any or all of those things.

Is it magic? Perhaps. Are we changing people’s lives? Yes, we are. Maybe only for the moment, but yes, we are.

And speaking of changing people’s lives, here’s how it happened to me. When two spontaneous, unconditional-loving, energy-changing, orange-and-white dogs charged into my world in 1999 and brought their blonde Jersey girl owner with them, my life changed.

The dogs’ names were Teigh and Belle. They were happy, enthusiastic, energetic Brittanys who loved everyone they met. I didn’t know it at the time and would have laughed if anyone had said it to me, but they were going to teach me about life.

The girl’s name was Cherilyn, and she was a graduate student at Seattle University pursuing her master’s degree in theology. Her thesis was going to be on animal-assisted therapy. She had heard me mention therapy dogs on the Westminster telecast and asked a mutual friend to introduce us so we could talk about therapy dogs. She had just started visiting Seattle’s Swedish Medical Center with Teigh, and she was competing with Belle at dog shows.

I was smitten by all three of them, and soon we were together. Cheri continued to pursue her degree, and I often served as the handler for Teigh and Belle, her “demo dogs,” in her presentations. I learned a lot from her as she worked her way through academia. Actually, I learned a lot about myself, as well—that was the life-changing part of the deal.

While all of this was going on, I still had my own public relations business in Seattle, and one of my clients was Delta Society, the world’s leading organization for therapy dogs. A great client, a nice fit, and Cheri was a big help in handling the production of their Beyond Limits Awards, which were presented annually to the therapy dog and service dog teams of the year.

I went with Cheri a few times on her therapy visits with Teigh, and I helped her with presentations at Seattle University and Providence Hospital. I thought I would try to become trained and registered with Belle as a therapy dog team as a way to learn about animal-assisted therapy. I thought that I could support Cheri and her work if I was involved myself, and I thought that we could do good things for people in need. But, admittedly, while helping people in need was a positive thing, at the outset my intent was mostly to learn about the work that my client did and to be supportive of my wife and her studies—what was to become her life’s work. Belle and I went through the training class and passed.

I did some visiting with Cheri at some of the places she had been working, but after watching her in action and hearing some of her stories about her other experiences, I thought I should see what it was like on my own with Belle. The first visit that Belle and I did was to an extended care facility in north Seattle. Visits to extended care facilities (they used to be called nursing homes) can be somewhat uncomplicated, as the people there are relatively quiet and the situation is not too stressful for the dog or the handler. I thought this would be the perfect maiden voyage for us.

The administrator greeted me, and I introduced him to Belle. She gave him the standard Brittany greeting: the butt wiggle, the lean-in, and the wagging tail. He loved her. Of course. I was certain that she would get the same reaction from the people we were about to visit, and I was anxious to get started.

The administrator walked us down the hall. He told me that he was bringing me first to Richard, a long-term care patient who had a photo in his room of himself with a Brittany. However, Richard was battling the early stages of dementia, the administrator told me, and I shouldn’t expect too much from him. Richard also believed that his family had simply dumped him in the facility to live out his days. “He’s not happy to be here,” said the administrator. “He’s rarely spoken and rarely smiled since he arrived here some three months ago.”

With that information, Belle and I entered Richard’s room. I was a little anxious and was hoping for just about any reaction from him—a smile, maybe a few words. We walked in, Belle tugging me along with her tail wagging and her body twisting in that Brittany kind of way. She apparently had not heard anything that the administrator had told me, and she was ready to make a new friend.

Instantly, we got the smile—and then some. Richard’s smile lit up the room, his face beaming, tears forming in his eyes. All at once, he became animated and vocal.

“Come here, you knucklehead,” he called to Belle, slapping his thigh. She jumped on his lap and he hugged her as the administrator’s eyes widened at this first show of emotion. I watched without speaking, but I was thinking, Geez, we’re already breaking the rules by letting her jump on his lap.

I decided, given what I had been told coming in, that this was a rule that could be broken for Richard. The interaction was exciting to watch, actually.

By the way he was talking to her, I quickly realized that Richard thought Belle was his dog. He confirmed that when he said to me, “Son, will you take care of her after I die?” When his tears started flowing, so did mine.

Belle could feel what was happening, and she was loving it. Here she was—the dog who runs through my house at about 40 miles an hour, the dog who chases pigeons, squirrels, and her brother throughout our urban neighborhood, now just patiently resting her head on Richard’s lap—looking him right in those tear-filled eyes.

When it was time to move on, Richard gave Belle a big hug, some more pets, and said good-bye. He was smiling. He was happy. Maybe just for that moment, but that’s the moment we have, the moment we want, and the moment we contribute to.

We wandered through the facility and had a couple more visits. Belle stuck her face onto the bed of another man, who was bedridden but smiling. She sat on a chair and went eye-to-eye with a woman who produced a smile that she apparently had never given in this place before. She lay on a bed next to another woman who couldn’t talk.

On the drive home, I realized that now I got it. Richard and those other people we had visited—we had made their day. Had we changed their lives? Well, at least for that day, we certainly had.

Eventually, I passed the evaluation with Teigh, and Cheri passed with Belle. I was ready to set out on my own with Teigh and Belle. I had lost a few friends from the dog show world to AIDS in the past ten years, so I thought I would volunteer in their memory at Bailey-Boushay House in Seattle, an AIDS hospice.

I understood the basics about hospices: that they are administering palliative care, and the idea is that they are helping people deal with the end of their lives. I really hadn’t been around a lot of death, and while I wasn’t reluctant to do what I could to help, it was going to be a new experience for me.

I came away from the volunteer orientation believing that Bailey-Boushay was good at this, but I was anxious to see the reality versus the classroom. To me, death was always sad; here, they were trying to show that passing peacefully could perhaps ease some of that sadness.

On our first day, Teigh and I showed up and went right to the nurses’ station. It seemed a little quiet, almost grim, but this came as no surprise. As soon as one of the nurses saw Teigh, she broke into a big smile, dropped to her knees, and started talking to him.

“Hey buddy, how are you?” Teigh lay down and rolled over onto his back, ready to make some new friends. “What’s your name?”

“He’s Teigh, and I’m David,” I said. “This is our first visit here.”

“Well, Teigh and David, we are so glad that you are here,” she said. I could feel that her remark was more than just some platitude. Another nurse joined in with the stomach rubs while several others watched and smiled, stopping what they were doing at the moment. We would always be greeted in this fashion at B-B. After a few visits, I could understand why.

People were dying there every day. I would come back every Tuesday and be unable to find one or two people that I had seen the week before. Sometimes it was expected, sometimes not. I am sure that the people who worked with this every day could find it a little grim, even if helping the dying was their life’s work. So I came to realize that here, visiting the staff was just as important as—maybe even more so than—visiting the patients. They, too, needed some revitalization, something to make them smile or just help them move on after losing a patient.

After working our way through the staff, we would have quite a variety of patients waiting for us. They all had different stories, and many of them wanted to share those stories with us, perhaps in kind of a cleansing process as they were preparing to die.

Their stories weren’t what mattered to Teigh or to me. We were there to get some smiles and some pets for Teigh, whether from a well-to-do gay man, a tough street person, or a woman dying of cancer. Teigh would crawl into bed with some of them, sit in a chair next to the bed with others, or just hang quietly in my arms. Already I found myself wanting to be just like Teigh, with his measured enthusiasm and his ability to draw out some difficult smiles.

Cheri soon finished her master’s degree and was ready for her residency at Swedish. About that time, the American Kennel Club (AKC) asked if I would do some work for them as a public relations consultant and public spokesperson. The AKC was headquartered in New York City but told me that I could do the job from Seattle. We made a trip to New York and, while we were there, Cheri was offered a residency at NewYork-Presbyterian/ Weill Cornell Medical Center. We decided that we would move to New York.

We were sad to leave Seattle but excited about the professional opportunities in New York. And out in New Jersey, Emily, my mother-in-law, was happy to get her daughter back home.

After a two-year residency at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell, Cheri spent a year as the chaplain and director of pastoral care at Terence Cardinal Cooke Health Care Center in New York. Then, Ronald McDonald House asked her to be its Catholic chaplain and director of family support. That turned out to be a life-changing offer for both of us. Ronald McDonald House is a home-away-from-home for families who would come to New York from all over the world. Here, they hoped to find answers for their children who were fighting battles with cancer and being treated at New York hospitals such as Memorial Sloan-Kettering, NewYork-Presbyterian, and New York University.

Meanwhile, the Westminster Kennel Club asked me to come and work for them. I had done their TV commentary on USA Network since 1990, so we were not strangers. They created a full-time position for me as director of communications, and I moved a few blocks south on Madison Avenue from the AKC to Westminster in 2003.

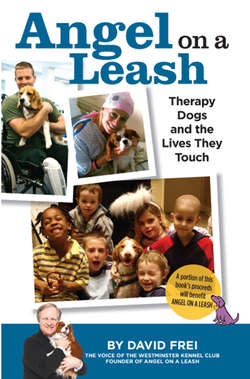

The following year, I suggested that Westminster consider creating and supporting a charitable activity that combined dogs with children—something to bring the club into a new part of the New York City community. We were very active in a number of dog-related charities, but as the kennel club of New York, we could do more. I suggested a therapy dog program at the NewYork-Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital, something that would bring us into the area of helping humans. I also suggested the name “Angel On A Leash,” and we all agreed that it was a perfect description. So we were off and running, soon adding Ronald McDonald House New York and Providence Medical Center in Portland, Oregon, as Angel facilities.

Anyone who shares his or her life with a dog understands intuitively the magic that dogs bring into our lives. I know what my dogs do for me, and I know what they do for others—no one needs to tell me why or how. Lately, though, science is catching up to our intuition. We are learning the physiology behind it all. Studies have shown that when you interact with a dog, whether it’s petting a dog or just looking at a dog and smiling, it increases the flow of endorphins, the “good” hormones, and that makes you feel better. When you feel better, your blood pressure goes down and your heart rate goes down.

We call it the therapeutic touch. There are more and more studies being published every day that back this up. Here are some, as reported by Delta Society:

• A 2005 study by the American Heart Association showed that heart patients visited by therapy dogs experienced a reduction in stress levels.

• A 2004 study by Rebecca Johnson, PhD, RN, of the University of Missouri-Columbia Center for the Study of Animal Wellness, showed that when a human pets a dog, it launches a release of hormones such as beta-endorphin, prolactin, dopamine, and oxytocin, all associated with good health. This was the first time that a therapeutic relationship between animals and humans had been scientifically measured.

• An earlier study at the State University of New York at Buffalo by Dr. Karen Allen evaluated forty-eight stockbrokers who were taking medication for hypertension. The study found that the brokers who were given a pet saw their stress levels drop significantly, and half of them were able to go off their medication.

• Studies reported in the American Journal of Cardiology in 2003 found that pet owners have shorter hospital stays, make fewer doctor visits, and take less medication for high blood pressure and cholesterol that those who do not own pets.

• The Chimo Project in Alberta, Canada, compared animal-assisted therapy with traditional therapy for patients in treatment for depression and anxiety in a twenty-seven-month project that began in 2001. The patients who met with therapists who used dogs in their sessions looked forward to therapy more, felt more comfortable talking to the therapists, and felt that they performed better at home and school than patients receiving traditional therapy. Patients who had pets were less depressed or anxious at the outset and showed lower scores on the depression severity scale after therapy than those who did not own pets.

But I found that it still is more than science and physiology. It’s spirituality, too. Dogs are faithful friends, gifts from whomever or wherever you believe they come from. They are blessings, and we give thanks for our blessings by sharing them with others.

About the time that Cheri came into my life and brought me Teigh and Belle, I read Tuesdays with Morrie, the great book by Mitch Albom. Mitch was a sports-writer from Detroit who rediscovered one of his college professors, Morrie, who was in the last months of his life. The book tells of a series of visits between the two men in which Morrie shares his life lessons.

Morrie talked about devoting yourself to loving others, devoting yourself to the community around you, and devoting yourself to creating something that gives you purpose and meaning. With all of that, Morrie said that you should choose to live a life that matters, offering to others what you have to give—specifically love and compassion. I never got to meet Morrie, but I did read the book. And just as good, I had Teigh and Belle to teach me about unconditional love. They helped me choose what I believe to be a life that matters. Teigh and Belle changed my life.

Their spontaneity and total honesty might just be what makes dogs so good at therapy work. Many of the patients we visit have to live their lives in the moment because, sadly, that’s all that they have. But that’s perfect for the dogs because they live their lives in the moment, too. And it’s perfect for our visits because we visit in the moment.

Perfect.

| “Therapy is about the dog and the patient, not about the handler.” |