Читать книгу Rising Star: The Making of Barack Obama - David Garrow J. - Страница 9

ОглавлениеChapter Three

SEARCHING FOR HOME

EAGLE ROCK, MANHATTAN, BROOKLYN, AND HERMITAGE, PA

SEPTEMBER 1979–JULY 1985

Eighteen-year-old Barry Obama arrived on Occidental College’s campus in Los Angeles’s far northeastern Eagle Rock neighborhood on Sunday, September 16, 1979. Upon arrival, he learned that his dormitory assignment was Haines Hall Annex, room A104, a small, three-man “triple.” Oxy, as everyone called it, had expected 425 entering freshmen but, on the day before Obama arrived, the number hit 434 before growing to 458. Of them, 243 were men and 215 were women. The students noted the unexpectedly tight quarters, but college officials were overjoyed, because for several years Oxy had been having a hard time both attracting and retaining academically qualified undergraduates.

Eighteen months earlier, college president Richard C. Gilman had told the faculty that the freshman class target was being reduced from 450 to 425 because for the last three or four years “admission had been offered to every qualified applicant,” Oxy’s student newspaper reported. Gilman confessed that some who were admitted “may not have been fully qualified.” Out of 1,124 applicants for the class of 1980, only 179 had been refused admission. To raise Oxy’s standards, a new dean of admissions and new staff were hired in mid-1977, but as of 1978 only 54.2 percent of students admitted to the previous four graduating classes had graduated in the normal four years. The class of 1980 was distinguished by the number of dropouts and students transferring to larger institutions. Oxy’s student newspaper interviewed sophomores about their plans, and in a front-page story reported that “it seems that at least half of them are not planning to return next year.” The “primary complaint is that the college is too small and limited” academically; other issues were “the limited social atmosphere, the immaturity of the student body and the lack of privacy on campus.”

Privacy didn’t get any easier with the advent of three-person triples, and Haines Annex and a second dorm each had three of these freshman rooms interspersed on hallways otherwise housing upperclassmen. Barry’s two roommates had arrived before him: Paul Carpenter had grown up in nearby Diamond Bar, California, and graduated from Ganesha High School in Pomona. Imad Husain was originally from Karachi, Pakistan, and he and his family now lived in Dubai; he had graduated from the Bedford School in England. Imad was one of many international students at Oxy; in contrast, this freshman class of 1983 included only twenty-plus African American students, mostly from heavily black neighborhoods in nearby South Central Los Angeles. Oxy’s tuition for the 1979–80 year was $4,752, with room and board adding another $2,100, for a total of just under $7,000.

Barry’s mother Ann Sutoro was earning a respectable salary from DAI in Indonesia—and, as the IRS would charge six years later, was failing to pay her U.S. taxes on it—and Madelyn Dunham still worked as a vice president at Bank of Hawaii. Decades later, an article in an Occidental publication would print Obama’s statement that he had received “a full scholarship” that he recalled totaling $7,700, and journalists would repeat that pronouncement as an unquestioned fact. But Occidental awarded financial aid only on the basis of financial need and, like Punahou, made work-study employment a part of any recipient’s financial aid package. There is no evidence in Oxy’s surviving records that support Obama’s statement about financial aid, and none of his Oxy classmates remember him working any on-campus job.

Classes began on September 20. Occidental operated on a quarter, or more accurately, trimester system—fall, winter, and spring. Most freshmen followed Oxy’s Core Program. A freshman seminar covered the basics of how to use the library and write a paper, easy indeed for anyone from Punahou. Distribution requirements mandated a sampling of American, European, and “World” culture courses across freshman and sophomore years, plus a foreign language—Spanish in Obama’s case, after his unfortunate early encounter with French at Punahou—but within that framework students had a great deal of choice. That fall Obama selected Political Science 90, American Political Ideas and Institutions, a lecture class of about 120 students taught in two five-week segments. The first, covering American political thought from Madison and Jefferson through Lincoln, the Progressives, the New Deal, and the mid-twentieth-century debate over pluralism versus elitism, was handled by Roger Boesche, a young assistant professor who had received his Ph.D. from Stanford in 1976. The second, covering the structure and powers of the federal legislative, executive, and judicial branches, was taught by Richard F. Reath, a soon-to-retire senior professor. Boesche in particular impressed Obama. One of his other enduring memories from freshman year was reading Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon, published just two years earlier, in an introductory literature course.

One hope Barry brought with him to Oxy was quickly diminished, namely any future as a collegiate basketball player, even at a small Division III school. Midday pickup games at Rush Gymnasium well in advance of preseason team practice—“noon ball” in the school’s parlance—quickly demonstrated that Oxy had plenty of players with talent well beyond what Obama had seen in Hawaiian high school AA games. Barry was still not a good outside shooter, and he was so left-handed he always drove leftward and could not cross over. His love of basketball would remain, but his final official team game had taken place in Honolulu six months earlier.

Instead Obama’s freshman year revolved around Haines Annex, with its mix of students crammed into tiny rooms on a narrow hallway with one alcove that offered an old couch of uncertain color. In addition to Barry, Paul, and Imad, a second freshman triple included Phil Boerner, a graduate of Walt Whitman High School in Bethesda, Maryland, whose father was a foreign service officer stationed at the U.S. embassy in London. Another triple just around the corner housed Paul Anderson from Minneapolis, a track-and-field athlete. A sophomore triple right across the hall had two Southern Californians, Ken Sulzer and John Boyer. A second next door included Sim Heninger, a North Carolina native who had grown up in Bremerton, Washington; a third had Adam Sherman, from Rockville, Maryland. Tight quarters made for open doors and quick, close friendships. One night early on Barry, Paul Carpenter, Phil Boerner, John Boyer, and others drove to Hollywood to see the movie Apocalypse Now, which had opened just a few weeks earlier. There was a long line; right in front of the Oxy crew was the well-known musician Tom Waits, who Phil remembered was “quite wasted.”

Getting wasted happened at Oxy too, and perhaps more in Haines Annex than in any other dorm. Loud music helped set the tone, and as Ken Sulzer drily recalled, “if there was an alcohol restriction in the dorms, I wasn’t aware of it.” But drinking wasn’t the half of it. “Choom” and “pakalolo” weren’t part of mainland vocabulary, but partaking was even more common in Haines Annex that 1979–80 school year than Barry’s trips up to Pumping Station had been a year earlier. Adam Sherman, who was an enthusiastic participant in what he later would acknowledge was a “very wild year,” wrote a short story describing the group of regulars who gathered at least four or five nights a week in the hallway alcove that Sim Heninger termed “a male sanctum.” The “threadbare couch” sat on a “cigarette-scarred” “aquamarine carpet which is littered with broken, stale potato chips” and “a few mangled and crushed beer cans.” Drawing from a ceramic “crimson bong,” “the dope” is passed from Paul Carpenter, whose blue eyes are “glazed over in pink, dilated inebriation,” to Imad and then to Sim Heninger. The early-morning scene ends with Paul waking Adam from a sound sleep on the hallway floor. Other nights proceeded more energetically, with Phil Boerner ruefully recalling how the regulars would “repeatedly break the fire extinguisher glass during late-night wrestling matches.”

Barry Obama was a nightly participant in the hallway gatherings. John Boyer, who kept an irregular journal over the course of the year, recorded how Adam was upset after one holiday break when Obama failed to bring something back for the group from the lush environs of Oahu. Carpenter remembered Obama as someone who “listened carefully” during hallway discussions; Michael Schwartz, a good friend of Carpenter’s and Anderson’s, remembered Barry as “reserved” and can picture him drinking beer out of a paper cup. Samuel Yaw “Kofi” Manu, a Ghanaian student who met Obama in the introductory political science class, recalls how “extremely friendly” Obama was; sophomore Mark Parsons, a fellow heavy smoker, remembers Barry telling him, “I smoke like this because I want to keep my weight down.” John Boyer still has an image of Barry and Adam having long, late-night conversations on the decrepit couch. Obama was “personable” and “quick to laugh,” with “a great sense of humor.” But Boyer notes that Barry was “always vague” about his family, and even during those late-night discussions, with beer and marijuana relaxing most everyone’s demeanors, “there was always kind of a wall” on Barry’s part. It was “not really aloofness,” Boyer explained, but something self-protective; Obama was more an observer than a spontaneous participant. “ ‘Remove’ is a good word,” Boyer concluded.

One Friday night in mid-October Barry, Sim, and a sophomore woman were sitting in Haines Hall proper, all under the influence of mood enhancers. In Barry’s case those included psychedelic mushrooms, and as a result, Obama “just came unglued. He was a mess.” Sim believed that Barry had been adopted and raised by an older white couple whose photo he once displayed, but this night, as Obama babbled about identity and nudity and not wanting to experience rejection, it seemed as if he “was pretty troubled” and was experiencing a “big crisis.” At bottom Barry seemed “uncomfortable and frightened,” as well as “hysterical and angry,” Heninger remembered. “There was no barrier between us in this moment,” but for Sim “it was difficult and uncomfortable” in the extreme. Eventually Barry “scraped himself together.” Given everything that had been consumed, Sim later mused that neither Obama nor the young woman probably remembered the experience at all, even though in Heninger’s eyes it was “a big deal. We called it a day and it blew over,” and “I never talked to him about it” again.1

For Thanksgiving 1979, just like on weekends “if there was wash to be done, or refrigerators to be raided,” Barry joined Paul Carpenter at Paul’s family home about thirty miles away. Mike Ramos, in college in Washington State, remembers some holiday in late 1979 when he picked up Greg Orme in Oregon and then rendezvoused with Barry and some others at Mike’s younger sister’s apartment in Berkeley, just east of San Francisco. Oxy had an almost four-week break after fall exams ended on December 6 and before winter term classes began on January 3, 1980, so Barry probably returned to Honolulu for a good chunk of that time, when Oxy’s dorms were closed.

When winter term commenced, Obama took the second course in the political science introductory sequence, Comparative Politics, which that year was taught by the campus’s most easily recognized and outspoken young faculty member, openly gay assistant professor Lawrence Goldyn. A 1973 graduate of Reed College in Oregon who had earned his Ph.D. from Stanford just months earlier, Goldyn was an unmistakable figure on Oxy’s campus. To say that Goldyn was out “would be an understatement,” political science major Ken Sulzer recalled. Goldyn was “funny, engaging,” and wore “these really tight bright yellow pants and open-toed sandals.” Gay liberation was not part of the Comparative Politics course, but Goldyn drew “a good-sized crowd” one evening during that term when he spoke on gay activism, and a column he wrote for the student newspaper ended by declaring that “the point of liberation, sexual or otherwise, is to rewrite the rules.”

Goldyn made a huge impact on Barry Obama. Almost a quarter century later, asked about his understanding of gay issues, Obama enthusiastically said, “my favorite professor my first year in college was one of the first openly gay people that I knew … He was a terrific guy” with whom Obama developed a “friendship” beyond the classroom. Four years later, in a similar interview, Obama again brought up Goldyn. “He was the first … openly gay person of authority that I had come in contact with. And he was just a terrific guy,” displaying “comfort in his own skin,” and the “strong friendship” that “we developed helped to educate me” about gayness.

Goldyn years later would remember that Obama “was not fearful of being associated with me” in terms of “talking socially” and “learning from me” after as well as in class. Three years later, Obama wrote somewhat elusively to his first intimate girlfriend that he had thought about and considered gayness, but ultimately had decided that a same-sex relationship would be less challenging and demanding than developing one with the opposite sex. But there is no doubting that Goldyn gave eighteen-year-old Barry a vastly more positive and uplifting image of gay identity and self-confidence than he had known in Honolulu.2

Gayness was not one of the subjects discussed every night in Haines Annex’s grungy alcove in early 1980. But the residents did talk about the Soviet Union’s recent invasion of Afghanistan. Then, on January 23, President Jimmy Carter in his State of the Union speech announced that he would ask Congress to register young men in preparation for possibly reinstituting a military draft to augment the U.S.’s all-volunteer forces. That news gave Oxy’s small band of politically conscious students a new issue to use to regenerate significant student activism.

Two years earlier, a trio of Oxy students—Andy Roth, Gary Chapman, and Doyle Van Fossen—had responded to a challenge posed by the well-known political activist Ralph Nader during an early 1978 campus speech. Occidental, Nader noted, had some $3 million of its endowment invested in more than a dozen corporations such as IBM, Ford, General Motors, and Bank of America that did business in South Africa, which was known for its harshly racist system of apartheid. In reaction, the undergraduate Democratic Socialist Fellowship formed a Student Coalition Against Apartheid (SCAA) to demand that Oxy divest its stock holdings in companies that continued to operate there.

SCAA quickly gathered more than eight hundred student signatures on a petition calling for divestment, but in early April 1978, Oxy president Gilman rebuffed the students’ request. A week later a protest rally of more than three hundred, including Oxy’s only African American faculty member, Mary Jane Hewitt, greeted a board of trustees’ meeting that affirmed Gilman’s refusal. Several weeks later Hewitt resigned from Oxy after she was denied promotion to a higher rank, and the trio of student leaders submitted an angry letter to Oxy’s weekly newspaper saying that in light of those two outcomes “we are forced to conclude that a racial bias permeates this institution.”

By the 1978–79 academic year, the trustees’ finance committee chairman, Harry Colmery, debated Gary Chapman, head of the newly renamed Democratic Socialist Alliance (DSA) at a campus forum, but then the board announced it had ceded investment decisions to a mutual fund, thus ostensibly rendering the entire issue moot. Oxy’s faculty responded in May 1979 by adopting a resolution condemning the board’s action, but in June the trustees again reaffirmed their refusal to divest.

In early 1980, the Los Angeles Times ran two stories about Oxy and its students that highlighted how significant increases in tuition and room and board fees would raise an undergraduate’s annual tab to $8,200 the next fall. Oxy’s student body was called “introspective” by one senior, and the reporter stated that “student life today” in Eagle Rock “seems placid, serene, contemplative.” Given that portrait, a turnout of more than five hundred students at an afternoon protest rally just a week after Carter’s nationally televised speech was a dramatic triumph for Oxy’s DSA. But a second meeting drew only 150 students, and a teach-in two weeks later attracted just sixty. As winter term ended in mid-March, a student newspaper headline signaled the short-lived movement’s demise: “Anti-Draft Activism Fades with Finals.”3

Oxy’s small black student population, about seventy in 1979–80, represented a marked decline from more than 120 just three years earlier. Academic attrition was high, the student paper reported, and after Mary Jane Hewitt’s resignation, two brand-new assistant professors, one in French, the other in American Studies, represented Oxy’s entire black faculty. A young black graduate of Vassar College was a newly hired assistant dean, but by spring she had submitted her resignation before a student petition effort led Oxy to successfully request that she withdraw it. Two black male sophomores, Earl Chew and Neil Moody, petitioned to establish a chapter of the Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity, citing “a serious social and cultural problem on campus” for minority students. Chew, a St. Louis native, had graduated from tony Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire and weeks earlier had taken the lead in creating an Oxy lacrosse team. But blacks at Oxy, Chew and Moody said, suffered from “a lack of cohesiveness, a generally present personal sense of being members of an ethnic minority group which cannot engage in collective achievement.” Indeed, when Oxy’s yearbook, La Encina, scheduled its 1979–80 photo of Ujima, the African American undergraduate group, only fourteen students showed up to appear in the picture. Barry Obama was not one of them.

Haines Annex’s short hallway was home to three other black male undergraduates besides Barry, sophomores Neil Moody and Ricky Johnson and freshman Willard Hankins Jr., but Obama did not develop relationships with any of them like he did with the crew of late-night alcove regulars. Most Oxy black students, particularly those from greater Los Angeles, stuck pretty much together. “There is a certain amount of minority segregation in the dining hall and in the quad,” the student paper observed. Black students who did not follow that pattern stood out.

Judith Pinn Carlisle’s African American mother had graduated from Howard University, her white father from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. She and her two siblings all attended junior high schools in Greenwich, Connecticut, but a family financial setback during Judith’s high school years had her living in South Central Los Angeles while she attended Oxy. Shy and quiet, “I kept to myself,” she said, and as a result, “I was challenged by many people on that campus as to my black legitimacy,” notwithstanding how “I’m living at Crenshaw and Adams” in the heart of black L.A. Earl Chew was a particular antagonist, treating Judith as if she was “a sellout,” she recalled. Chew “did not like me” and the hostility “was very disturbing.”

Sophomore Eric Moore’s mother had also graduated from Howard, and Eric grew up in mostly white, upper-middle-class Boulder, Colorado. “There weren’t that many black students on campus and there weren’t that many that went outside of the black clique,” he recounted. Eric had a diverse set of friends, including a junior from Karachi, Pakistan, Hasan Chandoo, who had grown up largely in Singapore and transferred to Oxy after a freshman year at Windham College in Vermont. Also from Karachi was sophomore Wahid Hamid, who roomed with French-born sophomore Laurent Delanney. Both Hamid and Chandoo had long known Imad Husain, Barry Obama’s roommate. By the spring of 1980 Chandoo was living off-campus with Vinai Thummalapally, an Indian graduate student who along with Hasan’s cousin Ahmed Chandoo was attending California State University and whose girlfriend, Barbara Nichols-Roy, who had also grown up in India, was an Oxy junior. As Eric Moore later said, they had “our own little UN there.”

Eric remembers Obama as always having “that big beaming smile,” and says he was “always in a Hawaiian shirt and some OP shorts and flip-flops.” Indeed, he says, Barry seemed “more Hawaiian and Asian and international in his acculturation than certainly he was African American.” Obama “hadn’t had an urban African American experience at all,” and at Oxy “many of the local Los Angeles African Americans were not as receptive to the cultural diversity” on campus as Eric was. Barry was “a little isolated from that group,” and just as Judith experienced, “there was some pushback from certain individuals.”

Earl Chew was the most widely visible African American student on campus, and while some found him hostile, Hasan Chandoo considered him a “really wonderful friend.” African American freshman Kim Kimbrew, later Amiekoleh Usafi, remembers Earl as “a bright and shining person” who was “just completely committed” to black advancement. Like Eric, she viewed Barry as “a really relaxed boy from Hawaii who wore flip-flops and shorts.” Obama once asked her to “come over here and talk to me,” Kim recalled. “I don’t know if he’d ever really been around black women at that point” and in terms of pursuing women, “he seemed to keep himself away from all of that.”4

Spring term began the last week of March and lasted until early June. Barry, along with Paul Carpenter, was in a third core political science course, this one on international relations and cotaught by professors Larry Caldwell and Carlos Alan Egan. Junior Susan Keselenko found Egan “a very romantic figure,” but the course itself was “really tedious.” A significant portion of it involved pairs of nine-student teams contending with each other in a multistage group paper exercise that Keselenko would remember as “very kind of mechanical.” Susan and a fellow junior, Caroline Boss, ended up in “Group Y” along with Barry; Paul Carpenter was in the opposing “Group A.” Boss, a political science major and active DSA member who as a freshman had run on the progressive slate for Oxy’s student government offices, served as the group’s informal leader. In mid-May Caroline and Susan orally presented Group Y’s six-page paper, “The MX Missile: Bigger Is Not Better.”

In the January State of the Union speech that had generated Oxy’s draft registration protests, President Carter also had proposed spending as much as $70 billion to build two hundred mobile, ten-warhead-apiece MX missiles that would be deployed all across the U.S. Southwest. Attacking Carter’s proposal as “an unnecessary, economically and environmentally devastating venture,” Group Y said that if implemented, the MX project “will destabilize the international balance, accelerate the arms race, and increase the likelihood of nuclear war”—the same themes that one group member’s father had publicly articulated exactly eighteen years earlier!

Whichever instructor gave it a C was not impressed. The paper had “a certain superficial fluency or glibness,” he wrote, but “it demonstrates a very great disregard for careful thought, little concept of how one analyzes an issue, and fails to make a persuasive argument.” Ouch. Carpenter’s Group A was hardly kinder in their critique, asserting that “Group Y’s paper as a whole lacked original analysis” and that “vital contradictions … undermined their thesis considerably.” Y then penned a rebuttal as well as their critique of Group A’s own paper, which addressed the 1978 Camp David Accords. The critique received an A even though it contained multiple obvious spelling errors, including “Palestenians,” and creation of the verb “abilitated.” Obama appears to have orally presented Group Y’s critique, for in the margin alongside their paper’s statement that “A settlement amenable to the oil producing Arab states does not insure an improved position for the U.S. in regard to oil,” one of his fellow students penned “Barry > abandon Israel will not protect U.S. oil access.”

Outside of class, regular activities from earlier in the academic year continued apace. Humorous event listings in the somewhat tardy April Fools’ issue of the student newspaper included one announcing that “Haines Annex will host a religious revival this Wednesday at 8:00. Participants will be asked to let their hair down for one night in an effort to communicate with extra-terrestrial Gods utilizing the means of herbal stimuli.” Just as at Punahou a year earlier, there was hardly anything secretive about some students’ recreational preferences.

One Saturday Barry, Eric Moore, and seniors Mark Anderson and Romeo Garcia went to a music festival in nearby Pasadena Central Park. Eric remembered that “we were culture and music hounds,” but with Oxy being an “island in the barrio” of surrounding Eagle Rock, Obama would join him on drives to South Central Los Angeles to get their hair cut. Sometimes the police pulled over Eric and Barry. “It was par for the course,” Moore explained years later.

The April 4, 1979, execution of former Pakistani president Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who had been deposed two years earlier in a military coup led by General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, had greatly intensified Pakistan’s political turmoil and also caught the attention of several Oxy students. Hasan Chandoo had grown up in a politically aware family, and his mother was a distant relation of Pakistan’s revered founder, Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Chandoo’s girlfriend Margot Mifflin, a sophomore who had started an Oxy field hockey team that Hasan volunteered to coach because he found its star player so attractive, knew best how “passionate” Chandoo’s hatred was for the military dictatorship. “I think I recall Hasan spray painting ‘Death to Zia’ somewhere on campus,” she later recounted. Pakistan was a regular topic of discussion in the Haines Annex alcove and even more so in the Freeman student union snack bar that everyone called the Cooler. Open during the day and then again from 8:00 P.M. to 11:30 P.M., the Cooler was the favorite hangout for Oxy’s most politically conscious students, like Caroline Boss, as well as for self-identified literati like Chuck Jensvold, a junior transfer from a community college who was five years older than his classmates.

By spring term 1980, Barry was an evening regular there too. “Obama always seemed to be in there,” smoking and drinking coffee, “just jousting back and forth with whoever would come,” Eric Moore remembered. One day when Barry walked into the Cooler, Caroline Boss from his political science class introduced him to Susan Keselenko’s roommate, junior Lisa Jack, an aspiring portrait photographer. Lisa already had been told that Barry was this “hot” guy, and seeing that he indeed was “really cute,” she asked if she could take a roll of photos of him. Barry readily agreed, and a few days later he walked over to Lisa and Susan’s nearby apartment. Wearing jeans, a dress shirt, and a leather bomber jacket with a fur collar, Barry also wore a ring on his left index finger, a digital watch on his left wrist, and a bushy Afro that was in need of a drive to South Central. Jack’s first fifteen photos captured Obama smiling and smoking while sitting on a simple couch. Then Obama doffed the jacket, rolled up his shirtsleeves, and put on a colorful Panama hat he had brought along. Jack shot eighteen pictures of Obama wearing the hat, then a final three of him bareheaded. Throughout them all, Obama looked without question happy, carefree, and very young for eighteen years of age.

Over a quarter century later, when Jack discovered her old negatives and sold publication rights for some of them to Time magazine, former Oxy classmates who had clear memories of Obama’s daily appearance during those years said the guy in the photos bore little resemblance to how they remembered him. “That’s not how he looked or dressed,” Eric Moore commented. John Boyer was even more succinct: “That’s not him.”5

After spring term exams, Barry spent some of the summer living with Vinai Thummalapally in the apartment Vinai and Hasan Chandoo had shared. Barry returned to Hawaii for at least part of the summer, and on July 29 he registered for the reinstituted military draft at a Honolulu post office. His almost ten-year-old sister Maya had landed in Hawaii twelve days earlier; their mother, Ann, apparently had arrived some weeks previously, because on June 15, a local attorney had filed her signed divorce complaint against Lolo in the same court where sixteen years earlier Ann had divorced Barry’s biological father. Ann’s filing said that “the marriage is irretrievably broken”; in a supporting document she stated that “husband has not contributed to support of wife and children since 1974,” was “living with another woman” and “wishes to remarry.” Ann reported that she was living “in 4-bedroom house provided by” DAI, her employer, and that she had “2 full-time live-in domestics.” The decree she and Lolo signed stated that Lolo “shall not be required to provide for the support, maintenance, and education” of Maya.

Ann and Maya were again staying with Alice Dewey, but Barry was back with his grandparents in their apartment near Punahou. As Obama later told it, one morning Stan and Madelyn argued over her wanting him to drive her to the Bank of Hawaii instead of her continuing her years-long pattern of taking a bus. Madelyn said that on the previous morning an aggressive panhandler had continued to confront her even after she gave him a dollar. Barry offered to drive her downtown, but Stanley objected. He said Madelyn had experienced this before and had been able to shrug it off, but now her fear was greater simply because this panhandler was black. That angered Stan, who refused to take her.

In Obama’s later telling, Stan’s use of the word “black” was “like a fist in my stomach, and I wobbled to regain my composure.” Stan apologized for telling Barry, and said he would drive Madelyn downtown. Then they left. Stanley’s obvious comfort with people of color, as well as his liberal political leanings, may not have been fully shared by now fifty-seven-year-old Madelyn, and in Obama’s recounting years later he added that never had either grandparent “given me reason to doubt their love.” Yet he was struck by the realization that men “who might easily have been my brothers” could spur Madelyn’s “rawest fears,” at least when they aggressively approached her at close quarters.

Obama says he went that evening to see Frank Marshall Davis, who was now approaching his seventy-fifth birthday. Frank’s poetry from the years before his 1948 move to Hawaii was now being rediscovered and studied by a younger generation of African American literature scholars, several of whom had interviewed Frank about his long and fascinating life. Barry recounted his grandparents’ argument, and Frank asked if Barry knew that he and Barry’s grandparents had grown up hardly fifty miles apart in south central Kansas at a time when young black men were expected to step off the sidewalk if a white pedestrian approached. Barry hadn’t. Frank remembered Stan telling him that when Ann was young, he and Madelyn had hired a young black woman as a babysitter and that she had become “a regular part of the family.” Frank scoffed at that patronizing, but told Barry that Stanley was a good man even if he could never understand what it felt like to be black and how those feelings could affect black people.

“What I’m trying to tell you is, your grandma’s right to be scared. She’s at least as right as Stanley is. She understands that black people have a reason to hate. That’s just how it is. For your sake, I wish it was otherwise. But it’s not. So you might as well get used to it.” In Obama’s telling, Frank then fell asleep in his chair, and Barry left. Walking to the car, “the earth shook under my feet, ready to crack open at any moment. I stopped, trying to steady myself, and knew for the first time that I was utterly alone.”

That night was apparently the last time Obama saw Frank Marshall Davis. But no matter how overdramatized Obama’s later account may have been, his previous nine months at Oxy had exposed him for the very first time to mainland African Americans who had a racial consciousness that a Hawaiian who had hardly ever experienced even minor racial mistreatment could not grasp any more than his sixty-two-year-old white grandfather could understand what four decades of being a black man in mainland America had taught his friend Frank. And black Oxy students from South Central L.A. or St. Louis had more trouble feeling at ease in a 90 percent white institution than someone from Punahou could. Barry Obama’s Oxy classmates were not being racially obtuse when they saw their happy, relaxed, and reserved friend as a multiethnic Hawaiian rather than a black American.6

Oxy’s fall term classes began at the end of September 1980. By then, Barry had accepted Hasan Chandoo’s invitation to share a two-bedroom ground-floor apartment in a small two-story, multiunit building at 253 East Glenarm Street in South Pasadena, a fifteen-minute drive from Oxy. Before the dorms opened, Hasan’s younger friend Asad Jumabhoy, an Indian-origin Muslim also from Singapore who was an entering freshman, crashed on their living room couch. Hasan had a yellow Fiat 128S, and Barry soon acquired a beat-up red Fiat coupe. Vinai Thummalapally and an Indian roommate lived upstairs, and Barry sometimes gave Vinai’s girlfriend Barbara a lift to or from Oxy.

Living off campus, Barry spent more time hanging out in the Cooler between and after classes. Cooler regular Caroline Boss cochaired Oxy’s Democratic Socialist Alliance, in which Hasan was active, and Hasan was also still coaching Margot Mifflin’s field hockey team. As Margot and Hasan got more involved, Margot and her roommate, Dina Silva, spent increasing time at Hasan and Barry’s apartment. “They had great social gatherings, parties, dinners,” Dina recalled, and Imad Husain and Paul Carpenter, still living in Haines Annex, plus Paul’s girlfriend Beth Kahn, were among the regulars. “They used to throw a great party there,” Paul agreed. “Food and dancing and a great mix of folks,” including Bill Snider and Sim Heninger from the old Haines Annex crowd plus Wahid Hamid, Eric Moore, and Laurent Delanney. Barry and Hasan went on outings with Wahid or Vinai and Barbara to places like Venice, where Margot took a photo of Barry, Wahid, Hasan, and Hasan’s cousin Ahmed all wearing roller skates.

Whether in the Cooler or at Glenarm, Hasan’s passionate interest in politics dominated many discussions. Hasan was “very outspoken about his political views, very aggressive, opinionated, extroverted,” Margot remembers, and identified himself as a Marxist—at least “to the extent that any of us knew what we were talking about,” as Susan Keselenko sheepishly puts it. Asad Jumabhoy concurs that “Hasan was very radical at the time” and “had very strong views and he could support his argument very well.” To Chris Welton, who returned to Oxy that fall after a year abroad and soon became a close friend after meeting Hasan in one of Roger Boesche’s classes, what everyone in Hasan’s circle shared was “an outlook” that contemplated the wider world beyond “the borders of the United States.” The crux of their orientation was “international, period,” or what Caroline Boss called a “more globalized perspective” than undergraduates who had experienced only the mainland U.S. could envision.

Irrespective of the venue, Hasan was “a force to be reckoned with,” Paul Carpenter recalls; Sim Heninger terms him “just a domineering personality.” Compared to Hasan, who “cursed like a sailor” while smoking incessantly, everyone saw Barry as quiet, measured, and reserved. Chris Welton remembers him as “a keen observer,” Caroline Boss would call him “mainly an observer.” Dina Silva thought of Barry as “quiet,” “thoughtful,” and “contemplative” during conversations. Obama “was listening and absorbing everything much more than being demonstrative,” Paul Anderson recalls. “He would watch people—that is what I remember,” artist friend and junior Shelley Marks recollects. “I specifically remember him being quiet and watching and observing.”

During the 1980–81 academic year, Barry and Hasan became the closest of friends. Hasan’s girlfriend Margot describes it as “an affectionate relationship,” one that “wasn’t hampered by masculinity issues. They were open with each other, affectionate with each other,” for Hasan was “an open, intimate, direct person.” Often the two of them would sit and study in their kitchen; Chandoo can picture Obama reading Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” at that kitchen table. Some nights Barry studied in a glass-enclosed area in the library’s basement that everyone called the Fishbowl. Other nights Margot Mifflin and Dina Silva would join Hasan and Barry to study on East Glenarm. Marijuana was a regular though perhaps not nightly relaxant for Hasan and Barry. “I got stoned with him many times,” Margot acknowledged when asked about that 1980-81 year. And, on a less regular basis, “we did occasionally snort cocaine” at Glenarm as well, although it was “not a routine part” of their lives at that time. Sim Heninger can remember nights of “uproar and hilarity” at Barry and Hasan’s apartment, but also at least one scene that was “a little scary for me.” Bill Snider, reflecting back on both Obama’s freshman and sophomore years, deftly remarks that “his memory may be a little hazy” both from those nights at Haines Annex and from the subsequent regular parties on Glenarm.7

In mid-October 1980 Roger Boesche and faculty colleague Eric Newhall failed badly in an effort to persuade Oxy’s faculty to adopt a resolution demanding that the college divest itself of stock holdings in companies still doing business in South Africa. Oxy’s student newspaper immediately noted that two years earlier student activism had forced the issue to the top of Oxy’s agenda. Just days later, Caroline Boss announced that she and friends were reviving the Student Coalition Against Apartheid (SCAA). Oxy president Richard Gilman dismissed divestment as “an altogether too simplistic solution” while nonetheless acknowledging “the racist conditions in South Africa,” but a young sociology professor, Dario Longhi, who had studied in Zambia, took the lead in organizing a series of expert visiting speakers on South Africa for late in the fall term. Earl Chew took an active role while also complaining that Oxy lacked a “multicultural curriculum and social life” and needed far greater diversity.

Sometime late in the fall term, Eric Moore and Hasan Chandoo had conversations with Barry Obama about his name. Eric had spent part of the previous summer in Kenya as part of Crossroads Africa, a student educational program that dated from 1958 and in which Oxy was an active collegiate participant. “What kind of name is Barry Obama—for a brother?” Eric asked him one day. “Actually, my name’s Barack Obama,” came the answer. “I go by Barry so that I don’t have to explain my name all the time.” Moore was struck by Barack. “That’s a very strong name,” he told Obama, who then raised the issue with Hasan one day while they walked across campus. Chandoo agreed, and liked Barry’s middle name too. While most close friends like Paul Carpenter and Wahid Hamid had called him “Obama” instead of Barry and stuck with that usage, from that day forward Eric, joined only by Bill Snider, began addressing him as Barack while Hasan, being Hasan, would sometimes say “Barack Hussein,” as Asad Jumabhoy clearly remembers even thirty years later. Margot Mifflin too “can remember Hasan saying ‘He goes by Barack now,’ and I said, ‘Well, what is Barack?’ and he said ‘That’s his name.’ ” At the time, she recalls, “it was jarring.”

Over a quarter century later, Obama would say that he saw the change from Barry to Barack as “an assertion that I was coming of age, an assertion of being comfortable with the fact that I was different and that I didn’t need to try to fit in in a certain way.” With his Oxy friends “he would never correct you” if he was addressed as Barry, Asad explains, but when Obama returned to Honolulu for Christmas 1980, he told his mother and his sister that from now on he would no longer use his childhood nickname and instead would identify himself as Barack Obama. But to his family, just as with Hasan, Eric, and Bill, the name change signified no break in who they thought he was. As Snider explained, “I did not think of Barack as black. I did think of him as the Hawaiian surfer guy.”8

Long breaks between academic terms gave Barack and his best friends plenty of opportunities to travel. One week Barack and Wahid Hamid headed down to Mexico, then northward to Oregon, in Obama’s red Fiat. Two days before the end of fall term exams, Hasan and Barack showed up in the Oxy library with a surprise birthday cake for Caroline Boss, who was hard at work on her senior thesis and whom they spoke with almost every day in the Cooler. Caroline invited the duo to stop by her family home in Portola Valley, near Stanford, over the holidays when Hasan and Barack would be on the road in Hasan’s yellow Fiat. Either before or after a New Year’s Eve party in San Francisco at which Hasan introduced Barack to another Pakistani friend, Sohale Siddiqi, Hasan and Barack arrived at midday at Boss’s home.

Her boyfriend John Drew, a 1979 magna cum laude Oxy political science graduate, was also there; he was in his second year of graduate school at Cornell University. Boss had spent the summer of 1980 in Ithaca taking summer classes, and Drew knew Caroline as “a fun, scintillating, hyper-extroverted,” and “intellectually vibrant” young woman who, despite her adoptive parents’ significant wealth, worked cleaning an Oxy professor’s home. That winter day in San Mateo County, the four young people headed out to lunch with Caroline’s parents; Drew recalled much of their conversation focusing on Latin America and particularly El Salvador. Back at the Bosses’ home, as Drew remembered it, he and Obama got into a “high-intensity” argument about the relevance of Marxist analysis to contemporary politics. Drew’s “most vivid memory” was how strongly Obama “argued a rather simple-minded version of Marxist theory” and that “he was passionate about his point of view.”

Drew recalled Obama citing the work of the late French Caribbean decolonization scholar Frantz Fanon. At Oxy Drew had been active in the democratic socialist student group, but a course that past fall with Cornell’s Peter Katzenstein had significantly altered Drew’s views. “I made a strong argument that his Marxist ideas were not in line with contemporary reality—particularly the practical experience of Western Europe,” Drew would recount years later. In Drew’s memory, “Caroline was a little shocked that her old boyfriend was suddenly this reactionary conservative,” but Obama shifted to downplay their degree of disagreement, conceding that there was validity to some of Drew’s points. Drew briefly saw Barack three more times during the remaining six months of his relationship with Boss before finishing his Ph.D., teaching at Williams College, and evolving into an ardent Tea Party conservative.9

Oxy’s 1981 winter classes began on January 6. For the first two weeks of January, Hasan’s friend Sohale, who now lived in New York City, joined them in the Glenarm apartment as they hosted almost nightly parties. For Barack, though, this new term would be by far the most academically and politically engaging ten weeks of his collegiate career. One course he chose, Introduction to Literary Analysis, was taught by English professor Anne Howells, who had been at Oxy almost fifteen years. Utilizing the popular Norton Introduction to Literature, Howells had her fifteen students devote the first five weeks of the term to a “close reading of poetry—old-fashioned textual analysis” and then five weeks to reading short stories. There was “not very much reading, but a lot of writing”—five papers in the course of ten weeks. Barack “spoke well in class,” Howells would recall, and submitted well-written papers, but “he wasn’t a really committed student” and was late with assignments more than once.

Obama also enrolled in English 110, Creative Writing, which met Tuesday and Friday mornings 10:00 A.M. until 12:00 P.M., with David James, an Englishman who had graduated from Cambridge in 1967 and earned his Ph.D. at the University of Pennsylvania in 1971. After teaching for nine years at the University of California at Riverside, James had arrived at Oxy just four months earlier. He required interested students to submit a writing sample prior to registration, an indication of the seriousness he brought to his teaching. At least five of the dozen or so students in the small class were earnest aspiring writers: Jeff Wettleson, Mark Dery, Hasan’s girlfriend Margot Mifflin, and Bill Snider and Chuck Jensvold, the older transfer student, both of whom Barack had known since his freshman year.

David James was “a marvelous character,” Dery recalled, “a classic British Marxist film theory jock” who was “a very penetrating analyst of poetry.” James handed out copies of contemporary poems he believed students would find stimulating, including ones by Sylvia Plath, W. S. Merwin, and Charles Bukowski, but viewed the course as “essentially a workshop to facilitate the students’ own compositions.” Jensvold’s presence was especially generative, for writing “seemed to define his whole being,” James remembered. In particular, Jensvold had an acute “eye for concrete detail” and knew that “amassing an inventory of details” was invaluable to a creative writer. Dery also appreciated Jensvold’s presence in what became “a very invigorating class.” Chuck was “an exemplar of the serious writer,” and as an older student he was “almost our mentor.” Dery and another classmate each referred to Jensvold as “hard-boiled,” and that classmate warmly remembered Chuck as “the Bogart of Occidental.”

Dery also recalled James as “a strict disciplinarian” who “didn’t suffer fools gladly” and had “zero tolerance for undergraduate lackadaisicalism.” A growing problem as the term progressed was students “straggling into class late.” One morning an angry James announced, “I am going to lock the door.” Soon a figure appeared outside the frosted glass door, unsuccessfully trying the handle. James did not react, nor to an ensuing tap or two on the classroom window. Finally Dery took the initiative to open the door, and in strolled Barack Obama. To Dery, Barack was “some species of GQ Marxist,” but an “almost painfully diffident” one whose “caginess,” even in the Cooler, made it hard to know “what he truly thought.”

A third course that winter was Political Science 133 III, the final trimester of Roger Boesche’s upper-level survey of political thought, this one covering from Nietzsche through Weber to Foucault. The fifteen or so students included Hasan as well as Barack’s former Haines Annex neighbor Ken Sulzer. Although memories three decades later would be hazy on the exact details, the results of two different assignments were notable in disparate ways. Sulzer and his friend John Boyer recalled seeing Obama heading into the library late one evening before an exam or paper was due. A day or so later, pleased with his own A-, Sulzer asked Barack what he had gotten, but Obama demurred. Sulzer grabbed Barack’s blue book and was astonished that Obama had gotten a higher A than he had.

Some weeks later, though, Boesche returned a paper on which he had given Obama a B. As both Barack and Boesche later recounted, within days, Obama encountered his young professor in the Cooler and asked, “Why did I get a B on this?” Boesche viewed Obama as “a student who gives incredibly good answers in class” but failed to consistently live up to his ability level on written assignments that required sustained preparation. In the Cooler, Boesche told Obama that he was smart, but “You didn’t apply yourself,” that he “wasn’t working hard enough.” Barack responded, in essence, “I’m working as hard as I can.” Boesche knew better than to believe that, but Obama would remain irritated about that B even a quarter century later, especially because Hasan Chandoo, not known for his academic diligence, received a higher grade for the term than did Barack: “I knew that even though I hadn’t studied that I knew this stuff much better than my classmates.” Obama believed Boesche was “grading me on a different curve, and I was pissed.”

Obama would allude to that experience a half-dozen times in later years, often not expressly mentioning Boesche but recounting how “I had some wonderful professors … who started giving me a hard time…. ‘Why don’t you try to apply yourself a little bit?’ And that made a big difference” in later years as Obama gradually came to appreciate that he was much smarter and far more analytically gifted than anyone who knew him at either Punahou or Occidental fully realized in those times and places.10

Early 1981 was just as significant politically for Obama as it was academically. A listless rally on the first day of classes resulted in an Oxy newspaper headline reporting “Students Lack Interest on Draft Issue.” Six days later, an evening appearance by Dick Gregory, the comedian and political activist, that Hasan played a lead role in engineering, attracted a huge crowd of 550. Greeted by the “thunderous applause,” Gregory then spoke for more than two hours, offering up a pastiche of loony assertions about election tampering and CIA and FBI involvement in the killings of both Kennedy brothers and Martin Luther King Jr., all somewhat leavened by countless humorous asides.

Two days later, a far more serious student forum explored all manner of prejudices at Oxy itself, with African American junior Earl Chew confessing, “Coming here was hard for me. A lot of things that I knew as a black student, that I knew as a black, period, weren’t accepted on this campus.” Three days later, in response to a flyer distributed on campus, Hasan and Barack drove to Beverly Hills to join 350 others in a silent candlelight vigil protesting the opening of a new South African consulate on Wilshire Boulevard. Relocation of the office there, from San Francisco, had attracted hundreds of protesters three months earlier when the consulate first opened. The vigil was cosponsored by the Gathering, a two-year-old South Central clergy coalition led by Dr. King’s closest L.A. friend, Rev. Thomas Kilgore, the L.A. chapter of King’s old Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and the antinuclear Alliance for Survival.

Four days after that event, Thamsanqa “Tim” Ngubeni, a thirty-one-year-old South African member of the African National Congress living in exile in Los Angeles, addressed a lunchtime crowd of students on Oxy’s outdoor Quad. Born on the outskirts of Johannesburg in 1949, Ngubeni had joined the South African Students’ Organization in his early twenties and moved to Cape Town. A friend of prominent student leader Steve Biko, Ngubeni was arrested by South African authorities and imprisoned for several months before leaving South Africa and eventually making his way to L.A. in 1974, three years before Biko was killed while in South African police custody. A soccer scholarship enabled Ngubeni to attend UCLA, where he helped initiate the Afrikan Education Project and led demonstrations against the Bank of America’s involvement in South Africa.

In his January 21 speech at Oxy, Ngubeni told the students that South African apartheid “causes human beings to be considered as second-class citizens within their own country, the place where they were born and raised.” ANC’s goal was for black South Africans to be “recognized as human beings” in a country that had “more prisons than schools.” Ngubeni defended the ANC’s own use of violence against the South African regime, emphasizing that “we’ve been negotiating with them all these years while they were shooting us down in the streets.” He challenged Oxy’s students to reconsider which banks they patronized given how Bank of America and Security Pacific, like IBM and General Motors, continued to do business in South Africa.

Ngubeni often preached that “if you live for yourself, you live in vain. If you live for others, you live forever,” and his remarks that day certainly made an indelible impression on at least one of his young listeners. Barack Obama would tell two student interviewers a quarter century later that his meeting an ANC representative was the first time he thought about his “responsibilities to help shape the larger world.” Hasan’s intense politicization and their drive to Beverly Hills for the candlelight protest against South African apartheid were, like Roger Boesche’s professorial reprimand, the beginnings of an evolution that would flower more fully in the years ahead.11

As winter term approached its midpoint, political events took place almost nightly. On Sunday evening, February 8, Hasan and Barack both attended a dinner held by Ujima as part of Black Awareness Month at Oxy. The next night Lawrence Goldyn delivered a scintillating talk, deftly titled “Why Homosexuals Are Revolting.” On Tuesday evening, Phyllis Schlafly, the conservative Equal Rights Amendment opponent, spoke at Oxy and was met with heckling from a trio of young men: Hasan Chandoo, Chris Welton, and Barack Obama. But the activist students’ primary focus was on the Student Coalition Against Apartheid’s upcoming divestment rally on February 18, scheduled to coincide with the next meeting of Oxy’s board of trustees. Oxy’s paper urged all students to attend since it “has the potential to be the most effective display of student initiative in recent years.”12

Three students took the lead in organizing the rally: Caroline Boss, Hasan Chandoo, and Chris Welton. Caroline and Hasan decided the roster of speakers, with Hasan recruiting Tim Ngubeni to return as their keynote speaker, while Chris and Hasan handled the logistics for the noontime gathering just outside Oxy’s administration building, Coons Hall. No one can remember who first had the idea of opening the rally with a “bit of street theater,” in which two supposed South African policemen dragoon a young black speaker who wants to quiet the crowd, but Hasan and Caroline were two of Barack Obama’s closest friends. Obama later wrote that he prepared for what he expected would be two minutes of remarks prior to being dragged off.

Margot Mifflin and Chuck Jensvold videotaped the rally for a class project. A large banner calling for “Affirmative Action & Divestment NOW” hung in the background. Two folksingers played “The Harder They Come” and the crowd sang along before Barack, wearing a red T-shirt and white jeans, stepped up to the microphone. It was too low, forcing him to hunch over it. Barack asked “How are you doing this fine day?” before declaring that “We call this rally today to bring attention to Occidental’s investment in South Africa and Occidental’s lack of investment in multicultural education.” The crowd cheered and clapped. Barack, with his right hand in his front pants pocket, nodded and resumed speaking. “At the front and center of higher learning, we find it appalling that Occidental has not addressed these pressing problems.” The crowd cheered again, and Barack continued, “There is no—” before Chris Welton and another white student suddenly grabbed him from behind and wrestled him offstage, much sooner than Barack had expected.

“I really wanted to stay up there,” Barack later wrote, “to hear my voice bouncing off the crowd and returning back to me in applause. I had so much left to say.” In his own fictional retelling, he spoke much longer than actually was the case. “There’s a struggle going on,” he imagined having said. “I say, there’s a struggle going on. It’s happening an ocean away. But it’s a struggle that touches each and every one of us. Whether we know it or not. Whether we want it or not. A struggle that demands we choose sides.” In his recounting, Barack had gone on for another seven or more sentences, drawing cheers from the crowd and imagining that a “connection had been made.” But as Margot Mifflin later wrote after watching the videotape she had long retained, Barack’s version was “factually inaccurate” and “Obama’s speech was not long enough to be galvanic, or really even to be called a speech.” A detailed account of the rally in the next issue of Oxy’s student paper did not mention the opening skit at all. “Led by chants of ‘money out, freedom in,’ and ‘people united will never be defeated,’ ” the story said the ninety-minute rally attracted a crowd of more than three hundred, plus several local TV news crews.

As a few Oxy trustees and even President Gilman watched, Caroline Boss introduced Tim Ngubeni, who spoke briefly before giving way to senior Sarah-Etta Harris, a Cleveland native, Philips Exeter graduate, and Ujima leader with a glowing résumé that included a semester’s study in Madrid and a summer fellowship in Washington, D.C. A photograph taken by sophomore Tom Grauman during Ngubeni’s remarks captured a tall, regal Harris standing well apart from Caroline, Hasan, Obama, and other friends, including Wahid Hamid and Laurent Delanney.

Harris warned the crowd that by continuing to invest in companies that did business in South Africa, Oxy’s trustees “are telling us that they support oppression over there and also over here.” She then spoke directly about Oxy. “I can count the number of black faculty on two fingers, and black student enrollment has been going down steadily.” Harris drew cheers from the audience when she said she found it “hard to believe that the trustees cannot redirect their investments to correct some of the problems we have right here on campus.”

Many viewed freshman Becky Rivera as the day’s star speaker. “We’re upset,” she announced, and they were “demanding answers and demanding action.” Margot Mifflin remembers several African American women jumping to their feet during Rivera’s speech and exclaiming, “Say it!” Rivera closed by declaring that “students are responsible for revolutions. Students have power. It starts on the campuses.”

The rally’s final speaker was Ujima president Earl Chew. Caroline Boss remembers him as “so angry and on fire” but also “a kind person.” Chew was a complicated figure because he “had this prep school background, but at the same time he was very street.” After almost three years at Oxy, he was “very disillusioned” with a college that was “so painfully white.” Chew denounced Oxy’s idea of a liberal arts education as “a farce,” and excoriated the college for “taking our tuition and investing it in the oppression of our ancestral people.” Divestment “may not change the apartheid regime, but it’s letting our brothers and sisters in South Africa know that we … know better than to oppress other humans for economic gain.” As the rally broke up, Rivera sought out Obama to congratulate him on his role. “He really had been on the fringes politically up until that point,” Rivera recalled. She told him, “I wish you would get more involved,” but rather than thanking Rivera, Obama was simply “noncommittal.”13

That evening Hasan and Barack hosted a party to celebrate everyone’s efforts. Caroline Boss remembers her exchanges with Obama that evening and, like Rebecca Rivera earlier, she was annoyed that he was openly moping rather than savoring his role. “I was really annoyed with him” when he started “yapping about how ‘I didn’t do a good job, and I could have said it better.’ ” As Boss recalled, “we all sort of went ‘Shut up! It was great. It was fine. You did what you were supposed to do. Move on.’ ” She was irritated that Barack viewed their group effort only in terms of himself. “The rally wasn’t about you developing your technique,” she spat out. “It was about South Africa, not you.”

Obama would recall a similar conversation with Sarah-Etta Harris, who had quietly befriended him a year earlier. Boss’s annoyance was grounded in the many discussions she had had with him in the Cooler, including ones about Obama adopting Barack in place of Barry. “A lot of the year’s conversations when they weren’t about politics was about identity, me talking about being adopted and him talking about sort of this weird experience of who’s his father and where’s his mother.” Caroline’s adoptive parents came from Switzerland, and were now wealthy, but Caroline’s maternal grandparents had been peasants who worked as a janitor and maid in an Interlaken bank. “I was very forthright about my own feelings about my adoptive state,” Boss remembers, and Barack was “absolutely” clear that he was wrestling with his own feelings about having been abandoned by both his birth parents. “That was something where he and I had a kind of a common understanding,” she explains, “of what it means to try to figure all that out.” Regarding his mother, Barack “was just very conflicted that she was absent so much,” yet given her resolute independence “he admired her enormously and of course found her irritating.”

Obama and Boss also discussed “class and race,” with Boss citing her grandmother’s story to argue the primacy of the former over the latter. Her grandmother had “a royal name,” Regina, despite her humble life circumstances, and Boss made Regina “a prominent part of some very intense conversations concerning the relationship between class and race.” She said Barack talked “about a lot of things that he’s seeing and feeling” with regard to race in the U.S. Boss said she would reply, “Yeah, but my grandmother in Switzerland—you have to see this internationally—my grandmother’s scrubbing those floors, and my mother and her brothers aren’t allowed to go into most of the town. The police will come and get them because they’re in the tourists’ place because they’re just these little local brats as far as the town council was concerned, so class is huge.”

Fifteen years later, Obama combined these reprimands into an account of how a woman named “Regina” upbraided him after he responds to her kudos about his skit with cynical sarcasm, saying that it was “a nice, cheap thrill” and nothing more. Regina replies that he had sounded sincere, and when Obama calls her naive, Regina counters that “If anybody’s naive, it’s you” and tells him his real problem: “You always think everything’s about you…. The rally is about you. The speech is about you. The hurt is always your hurt. Well, let me tell you something … It’s not just about you. It’s never just about you. It’s about people who need your help.”

In Obama’s telling, that night at the party another friend approaches and recalls the awful messes they had left in the Haines Annex hallway a year earlier for the poor Mexican cleaning ladies, to which Barack manages a weak smile. “Regina” angrily asks Obama why he thinks that’s funny. “That could have been my grandmother,” she said. “She had to clean up behind people for most of her life. I bet the people she worked for thought it was funny too.” In truth, it was not Harris but another African American woman, young American studies professor Arthé Anthony, who had objected when someone mentioned the dorm messes during a conversation in Barack and Hasan’s kitchen.

In future years, Obama would embrace the mantra of “It’s not about you” as a core life lesson and as a powerful antidote to what he described as “the constant, crippling fear that I didn’t belong somehow.” He would invoke the story of a cleaning lady “having to clean up after our mess” on subsequent occasions both obscure and prominent, and would cite a friend’s rebuke about her grandmother having cleaned up other people’s messes. With one interviewer, Obama would fuzz the details, saying, “I remember having a conversation with somebody and them saying to me that, you know, ‘It’s not about you, it’s about what you can do for other people.’ And something clicked in my head, and I got real serious after that.”

Obama would recite the moral of the story—“It’s not about you. Not everything’s about you”—without naming Harris, Boss, or Anthony. In one rendition, Obama said the rebuke had come from a female professor, but in his written account of that night, he gave Regina the biography of the tall, regal Sarah-Etta Harris. His physical description of Harris was distorted—only her “tinted, oversized glasses” match up to the Harris of 1981—and he says she was brought up in Chicago, not Cleveland, but the other history he attributes to “Regina” is drawn from Harris’s own undergraduate achievements. Most of Obama’s Oxy friends have difficulty remembering Harris, but “Regina” leaves Oxy “on her way to Andalusia to study Spanish Gypsies.” A 1981 Occidental promotional prospectus highlighted Harris’s receipt of a Watson Fellowship and said she “will travel to Hungary, France, Italy and Spain to study the socio-economic problems of sedentary gypsies of those countries.” Obama’s account accurately details the lifelong impact that Harris’s, Boss’s, and Anthony’s rebukes of his self-centeredness had on him, but the “Regina” story merges no fewer than three conversations into one.14

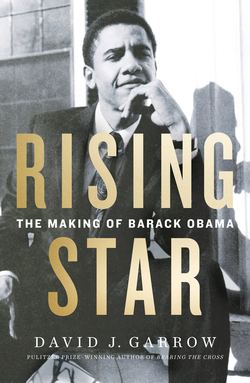

The same issue of the Oxy newspaper that covered the rally on its front page also featured “Rising Above Oxy Through Columbia.” Junior Karla Olson wrote that a year earlier she had been “stuck in a rut” at Oxy. Deciding that she needed to try another institution, “I tried to pick a college the polar opposite of Oxy” and “within a month I had applied and been accepted as a visiting student to Columbia University in New York City.” Upon arriving there, she had been presented with “Columbia’s catalogue of 2,000 or more available classes,” a stark contrast to tiny Occidental. Olson knew Columbia was “an Ivy League school,” but “I soon realized that I wouldn’t have to work nearly as hard as I do at Oxy.” Olson lived in Greenwich Village, where she had easy access to “museums, art galleries, Broadway, Fifth Avenue, Central Park, clubs, bars, restaurants, and a myriad of other diversions.” It seemed as if “95 percent of Columbia students live off-campus, and most go straight home from class … making it really hard to meet people,” but “my overall experience at Columbia was fantastic…. I learned a lot from my classes and benefited even more from the opportunities New York offered in my spare time.”

At Occidental, many if not most students thought about transferring to larger institutions. Eric Moore, who tried unsuccessfully to transfer to Stanford, believed “most people were trying to transfer from Oxy,” and Phil Boerner, Obama’s across-the-hall friend from Haines Annex, “wanted to attend a larger university” and one that was less “like Peyton Place” than Oxy, where “everybody knew who was dating who.”

Nineteen-year-old Barack Obama had never even passed through New York City, and he knew no one there aside from Hasan’s friend Sohale Siddiqi, but one day he asked Anne Howells, his literature professor, if she would write a letter of recommendation for him to Columbia University. “He wanted a bigger school and the experience of Manhattan,” Howells recalled years later. “I thought it was a good move for him.” Oxy assistant dean Romelle Rowe remembers Barack discussing a transfer to Columbia and saying he wanted “a bigger environment.” Years later Obama would say he transferred “more for what the city had to offer than for” Columbia, that “the idea of being in New York was very appealing.” Crucial too was how his closest friends were soon leaving Occidental. Hasan and Caroline were graduating in June and both were headed for London, Hasan to join his family’s shipping business and Caroline to study at the London School of Economics. Wahid Hamid, in a dual degree program, was about to shift to Cal Tech.

Caroline Boss, with whom Barack spoke most days, agrees that “he did have a lot of us who were graduating,” but “he definitely felt the need to transfer,” and not just because his closest friends were leaving. The biggest factor was Obama’s emerging belief that he ought to make more of himself than he felt able to do at Oxy. When Caroline and Barack discussed their families, he always said “that his father was a chief” of some sort among Kenya’s Luo people and that that lineage represented something he should be proud of, “something to live up to.” A quarter century later, Obama would reflect that if “you don’t have a sense of connection to ancestors … you start feeling adrift and … you start maybe devaluing yourself and internalizing” self-doubts. Pride in one’s roots can offer “a more powerful sense of direction going forward.” Obama’s conversations with Boss gave him his first-ever opportunity, far more so than with any friend from Punahou or even the voluble Hasan, to verbalize his developing thoughts about the kind of person he thought he should try to become.

Boss remembers “he basically said, ‘I’ve got to bail. I’ve got to get myself to where it’s cold. I have to be in the library’ ” and someplace where he would have “ ‘access to a black cultural experience that I don’t actually know’ ” and that would “ ‘make me an American and not just this cosmopolitan guy.’ ” As Boss remembers, they “talked about why it was important to be Barack. We talked about why it was important to be a man, and why that meant leaving Oxy because he was just going to hang around being a stupid little boy, smoking cigarettes and … never getting the A that he knows he’s perfectly capable of because you kind of slide.”

Obama also realized that the beer drinking, pot smoking, and cocaine snorting that Oxy, like Punahou, offered him, and that had cemented his reputation as “a hard-core party animal” to some friends, was incompatible with any self-transformation into a more serious student and person. Sim Heninger and Bill Snider believed that Obama’s decision to apply to Columbia sprang from a desire for greater self-discipline, and over a quarter century later Obama would remark, “I think part of the attraction of transferring was it’s hard to remake yourself around people who have known you for a long time.” He knew he was at a “dead end” at Oxy and needed a fresh start, that “I need to connect with something bigger than myself.” So when Barack mailed his transfer application sometime just before Oxy’s spring break began on March 20, at bottom he was making “a conscious decision: I want to grow up.”15

For Oxy’s spring term, Barack, along with scores of other students, enrolled in Lawrence Goldyn’s PS 115, Sexual Politics, which met Tuesday and Thursday afternoons. His old Haines Annex friend Paul Anderson took it too and recalls “many times having to stand in the back because there weren’t any chairs left.”

A new regular for the daily conversations in the Cooler was sophomore Alex McNear, who had arrived at Oxy the previous fall as a transfer from Hunter College in New York City, where she lived. By the end of winter term, she and fellow sophomore Tom Grauman had decided to start a literary magazine at Oxy. They announced the launch of Feast in the Oxy newspaper and invited submissions of short stories and poems for spring term.

Obama had composed two poems in David James’s winter term creative writing seminar, and he had presented each in class sometime late in the term. One, a twelve-line composition entitled “Underground,” may be no more comprehensible now than it was in 1981:

Under water grottos, caverns

Filled with apes

That eat figs.

Stepping on the figs

That the apes

Eat, they crunch.

The apes howl, bare

Their fangs, dance,

Tumble in the

Rushing water,

Musty, wet pelts

Glistening in the blue.

The second, titled “Pop,” made enough of an impression on his listeners in March 1981 that at least two of them still recalled that morning three decades later.

Sitting in his seat, a seat broad and broken

In, sprinkled with ashes,

Pop switches channels, takes another

Shot of Seagrams, neat, and asks

What to do with me, a green young man

Who fails to consider the

Flim and flam of the world, since

Things have been easy for me;

I stare hard at his face, a stare

That deflects off his brow;

I’m sure he’s unaware of his

Dark, watery eyes, that

Glance in different directions,

And his slow, unwelcome twitches,

Fail to pass.

I listen, nod,

Listen, open, till I cling to his pale,

Beige T-shirt, yelling,

Yelling in his ears, that hang

With heavy lobes, but he’s still telling

His joke, so I ask why

He’s so unhappy, to which he replies …

But I don’t care anymore, ’cause

He took too damn long, and from

Under my seat, I pull out the

Mirror I’ve been saving; I’m laughing,

Laughing loud, the blood rushing from his face

To mine, as he grows small,

A spot in my brain, something

That may be squeezed out, like a

Watermelon seed between

Two fingers.

Pop takes another shot, neat,

Points out the same amber

Stain on his shorts that I’ve got on mine, and

Makes me smell his smell, coming

From me; he switches channels, recites an old poem

He wrote before his mother died,

Stands, shouts, and asks

For a hug, as I shrink, my

Arms barely reaching around

His thick, oily neck, and his broad back; ’cause

I see my face, framed within

Pop’s black-framed glasses

And know he’s laughing too.

David James can remember Obama “reading that or an early version of that,” and particularly the “amber stain” reference to urine, because of “how powerful an image it was.” But James thought the poem seemed “dispassionate” because it was “neither sentimental nor cruel.” Margot Mifflin, no doubt with “Underground” in mind, noted that Obama’s “previous poems had been more abstract and fanciful,” but “Pop” made a stronger impression because of its “honest ambivalence and because it was so unabashedly personal, especially coming from someone who tended to be reserved.” Mifflin was also impressed that “it wasn’t sentimental. It had an edge of darkness to it, and that made it genuine.”

Alex McNear and her colleagues accepted both of Barack’s poems for Feast’s inaugural issue. When the fifty-page magazine arrived on campus in May, a review in the student newspaper described it as a “most outstanding collegiate example of writing talent” and said copies “should be sent to other colleges.” McNear and her contributors appreciated that praise, and over a quarter century later, Feast would be discovered by a new generation of readers who sought to understand Obama’s poems. Given both the title and the reference to “black-framed glasses,” most commentators presumed that Obama had written about his grandfather, Stan Dunham, not Frank Marshall Davis. But hostile critics focused on how the subject “recites an old poem he wrote before his mother died” and noted that Stan’s mother had killed herself when he was eight years old, yet Barack would forcefully reject the Davis hypothesis. “This is about my grandfather.”16

Alex McNear was one of two Occidental women whom male students immediately remembered three decades later. The list of men who actively sought her attention included 1980 graduate Andy Roth, who was in Eagle Rock through February 1981; Phil Boerner, who invited Alex to brunch multiple times; and Feast cofounder Tom Grauman, who found her “a magnetic force” before shifting his gaze to Caroline Boss. But interest in Alex ranged far wider. One upperclassman imagined she was “the most beautiful lesbian I ever knew,” and Susan Keselenko recalled that “everybody had a crush on Alex.”

McNear was unaware of the full degree of interest in her, but she was curious about one fellow sophomore she got to know in the Cooler during spring 1981. To Alex, Barack was “intriguing and interesting and smart and attractive,” and they spoke regularly as the school year wound down. Some friends believed the interest was mutual. “I thought he was pursuing her,” recalled Margot Mifflin, Occidental’s other unforgettable woman. She and the dashing Hasan Chandoo had been a steady couple the entire year, but that did not lessen Margot’s own “magnetism,” Tom Grauman noted. “It’s hard to forget Margot,” said Paul Anderson. “She had a way about her that was captivating.” Chandoo too was a compelling presence. When one classmate compared Hasan to the singer Freddie Mercury, Margot coolly suggested the handsome actor Omar Sharif instead. But perhaps Tom Grauman’s most striking photograph from that spring captures an enchanting Margot addressing a slightly blurred Barack. In contrast, a survey publicized in the student newspaper reported that 32 percent of Oxy women and 17 percent of men admitted that they had never had sex.17

Oxy’s black students remained politically marginalized despite the almost nonstop efforts of Earl Chew, who by April was trying to get support for a Black Theme House dormitory. Only nine African American students turned out for Ujima’s annual photo, and when a five-page Black Student Directory was distributed during winter term, one perplexed undergraduate sent a letter to the student paper that asked, “Why does the Oxy black community need their own directory; don’t they know who they are?” Whoever compiled it did not know Obama well, because it spelled his given name as “Barrack.”

Oxy president Gilman announced there would be no further discussion of divestment, yet the controversy continued to percolate even years later. In May Earl Chew, along with Becky Rivera, ran successfully for top student government positions, but Chew’s close girlfriend from that year later said she had no memory of Barack working with them at all.18

Instead Barack and Hasan channeled their energies into a newly created Oxy chapter of the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador. CISPES had been founded six months earlier to oppose U.S. aid to El Salvador’s military government, whose violent death squads had assassinated Roman Catholic archbishop Oscar Romero while he was offering mass in March 1980. CISPES supported El Salvador’s left-wing opposition, the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), whose ties to the Salvadoran Communist Party had led the FBI to investigate CISPES even before Barack and Hasan helped start Oxy’s chapter in early March 1981.