Читать книгу The Most Important Thing - David Gross - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

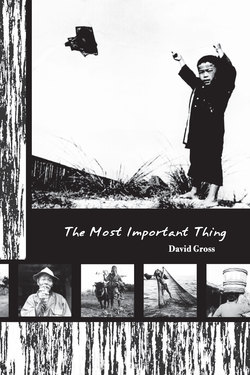

ОглавлениеEvery few hours, the planes of the U.S. Air Force and Army flew over Fort Bragg. Every time Kentuck saw one, he remembered his first view of an airplane in flight. The sight filled him with envy that someone had wings to fly over the mountains and all the troubles in them. The appeal of flight struck the young man. Desiring wings of his own, Kentuck admired the birds, even the lowly crow. Kentuck stowed this dream with all of the others in a corner of his mind where children keep dreams too wonderful for adults to know. Alas, the reality of gravity and the fetters of traditional life anchored his feet to the ground.

In his first year of high school, Kentuck studied the science of flight. The teacher launched the lesson with the story of the brilliant engineer Daedalus who fashioned wings from feathers and wax to escape Crete. Daedalus and his son Icarus experienced man’s first flight. The curious Icarus flew higher to observe the brilliant sun. Daedalus warned his son against soaring to the heights. Icarus ignored his father flying so near to the sun that the wax in his wings melted. The wings of the young man disintegrated, Icarus fell into the abyss. Daedalus flew on to freedom. The teacher continued the lesson describing lift and drag, noting the shape of a bird’s wing. As always when discussing the pioneers of flight, the Wright brothers figured prominently with their American invention, the airplane.

It was a dream come true for the young man to fly in an airplane. Kentuck had never flown before and now he found himself committed to jumping from airplanes. He reported for Airborne Training—”Jump School,” thirty-day special military training conducted at Fort Bragg.

Airborne Training is physically demanding. Yet, the institutional routine comforted Kentuck. Every morning broke with the metal cock crowing “Reveille,” and the barracks exploded with beehive intensity. Kentuck, with the forty other groggy boys, sprang from his metal bed. They shaved, dressed, and made their bunks. The meals came routinely like waves in the ocean. Each flux nourished the hungry young men. Exercise and adventure filled each day.

The men marched wherever they went. Marching in formation developed uniformity in the company. The recruit felt camaraderie and togetherness each time his left foot hit the pavement at the same moment as a hundred other men. The cadence call measured each step like the beat of a drum. In some calls, the recruit joined in. The DI sang, “You had a good girl, but you left.” “You’re right!” the recruits responded with the right foot hitting the pavement in unison. “You had a good home, but you left,” sang the DI. “You’re right!” sang the troops. “You want to go back, but you can’t,” reminded the DI. “You’re right!” responded the men of the company as one, with every right foot hitting the pavement as the men shouted “right!” The rhyming cadences kept time and occupied the mind. Cadences were funny, vulgar, or occasionally fatalistic, “If I die in a combat zone, box me up and send me home.”

Jump School challenged the soldier. Youthful, tough Kentuck drove to succeed. Of all the exercises, squat jumps demanded the most physically. To perform a squat jump, the recruit placed his hands behind his head. Then, he stood with one foot far in front and the other foot far behind, and in this wide stance the recruit squatted down low. Then, jumping high, he reversed his feet in the air and squatted down again upon landing. That is one squat jump. After about a hundred squat jumps rubbery legs made standing difficult.

Physical challenges ejected marginal troops from the elite Airborne like a spent cartridge shell. Those lacking the physical toughness or, more likely, the mental toughness failed. The grueling training passed only the best. An Airborne troop is a top troop.

Each day the men faced the regiment of eating, running, climbing, push-ups, sit ups, squat jumps, and finally, sleeping. When the moon slipped into the blanket of the night sky, each recruit slipped into his bunk. After weeks of sleeping bags in the field, the bunks felt like heaven. At the end of the day, Taps eased them into the comfort of slumber. Like anything else in life that is reliable, the Army routine soothes. Routine, not religion, is the opiate of the masses.

Before the Airborne soldier could fight the enemy, he fought gravity. Each day the men conducted exercises designed to lessen the fear of leaping from heights. Kentuck’s company trained by simulating jumps, but nothing resembles that first leap into the great void. When the day of the first jump arrived, Kentuck’s company planned a jump from the “Flying Boxcar.” The Air Force C-119, the first plane designed for parachuting, resembles a flying box. The plane hauled men and equipment, thus, the boxcar. The jumpers sat nervously inside the rumbling belly of the plane. On the early training flights, apparent clues betrayed strained emotions of the virgin jumpers. Kentuck sat uneasily but quietly in the plane as the big propellers roared to life. The plane rolled down the runway and leaped into the sky. For the first time in his life, Kentuck flew. He felt the luckiest man on earth. Kentuck knew in moments, he would jump through the open door. Kentuck studied the potential outcomes acknowledging the bad. Suddenly, even fifty extra dollars a month didn’t seem worth it.

The jumpers faced each other on narrow benches, checking laundrybags. (The flyboys called a parachute a laundry bag. A jumper carried one in front for emergencies and the main chute in the back.) Usually, eighteen jumpers sat in two rows of nine. With the aircraft flying at a relatively low altitude, a short flight lifted the jumpers to the drop zone. Upon the command, “Stand up and hook up!” the reluctant jumpers stood and attached their stay lines to a metal cable that ran from the front of the cabin to the back.

“Make your final inspection and sound off!” the jumpmaster yelled in the noisy plane. Each jumper scrutinized his parachute and emergency parachute. Upon the final verification of equipment, the jumper nearest the port in the plane yelled, “Number One is OK!” The second from the front yelled, “Number Two is OK,” and so on until the last jumper verified his equipment. Then, the jumpmaster signaled the pilot. The pilot sounded the alarm, signifying “Ok” for the jump. Then, in single file the jumpers waddled to the loving arms of the jumpmaster.

The jumpmaster was the master of ceremonies, ensuring an orderly interval between jumpers. One by one, the men leaped from the plane. The ripcord of the main parachute pulled the static cord dragging the chute from the bottom. It was almost impossible for the parachute to remain closed. Privates would die in droves otherwise. The Army is built on mechanisms that prevent the common soldier from error. If his chute didn’t open, the jumper waited three seconds and then pulled the ripcord of the second, emergency parachute. A jumper falls three hundred feet in three seconds. During a jump, a second seems like an hour.

Kentuck waddled to the open door of the airplane. He looked down at the frightening view. Kentuck thought of the extra fifty dollars a month realizing something he heard all his life was true. Money is the root of all evil. The epiphany hit him like a lightning bolt. He turned his head to relay his insight to the jumpmaster, but the jumpmaster fixed his hand to the back of Kentuck’s belt. The jumpmaster tossed him out of the plane.

Air rushed over his cheeks, causing them to flap like bloomers on a clothesline in a gale. His eyes watered. His helmet roared. When the cushion of air filled the canopy Kentuck jolted upward receiving the most intense wedgie imaginable. When the chute halted Kentuck’s fall, his guts fell into his jump boots. As the terror subsided, he drifted slowly to earth with his buddies. What a vantage point he had for the rest of the ride! With the canopy open pushed by moderate winds, he felt as safe as in his Ma’s loving arms. Below lay a newly plowed field, void of trees or power lines. The Army plowed the field, ensuring soft landings for the novice jumpers. Kentuck perceived the whole world, horizon to horizon. For a few minutes he reigned, the king of the world overlooking his realm. The common soldier is king of the world only briefly. Soon Kentuck glided to the earth with both feet and knees together, tumbled, rolled the chute, and scampered away. Pray another jumper doesn’t land on yoU.Soldiers weigh a ton. What a ride! The most frightening rides are always the most fun.

Since parachuting is merely a means of commuting to work, the soldiers carried their tools with them. Kentuck’s company prepared for combat as they floated to the ground. The airborne infantryman carried a full field pack, rifle, and two “laundry bags.” A soldier carried his water, food, shelter, medicine, weapon, ammunition, as well as any personal items he wanted. With so much to carry, few personal items were desired. The great number and weight of the required martial implements left little space for mementos. A picture of a loved one from home made the sum of the personal items carried by most soldiers. A measure of a man was expressed by what he valued enough to carry with him.

Jump training continued for a month When Kentuck leaped from the plane he screamed, “Wheeeeeeeeee!” This anthem disguised Kentuck’s fright from his company, and maybe, Kentuck faked himself too. His wheeeeeeeeee scream controlled what was difficult to control. As the days flew by, jumping became fun. In his bunk at the end of a day of wild excitement Kentuck prayed. Then, as he closed his eyes to sleep, Kentuck delivered his own eulogy. He prayed that when he drew his last breath, his last utterance would be “Wheeeeeeeeee!”

Meanwhile, the events erupted in Korea. The battle-hardened invaders enjoyed great success. For many years the North Korean People’s Army or In min-gun fought with Mao in the Chinese Communist Revolution. Now, after years of combat experience, and with the massive T-38 Russian tanks, they expected to defeat the Republic of Korea within six weeks. On June 28, 1950, Seoul fell. On July 5, the U.S. Army entered the fight. Some Americans thought that the North Koreans would retreat upon seeing that first American uniform. They didn’t. The downsized American Army was unprepared for a foreign war. Soldiers from all over the world migrated to Korea. The Army sent men straight from Basic Training. Realizing his first combat jump may soon fall on Korean soil, Kentuck trained hard.

The company parachuted until each soldier obtained the minimum number of jumps required for airborne certification. Upon certification they became official members of the Death from Above Club. The members of the Airborne received the winged parachute emblem for their uniform. It was an emblem worn with pride. More importantly, as long as Kentuck maintained his certification for Airborne, he received the bonus fifty dollars each month. Certification maintenance required one jump per month.

Although Kentuck did not know it at the time, two months of Airborne pay was all the Airborne pay he would receive. Contrary to the promises of the recruiter, the Airborne pay evaporated. For the next year, Kentuck served as an infantry rifleman. At the front, Kentuck never jumped. Within a short time, he lost his airborne qualification. After that, Kentuck didn’t receive his extra pay.

At last, Kentuck graduated from Jump School. His birthday paled in comparison to the glory of that wonderful day. Kentuck was Airborne. The spirit, training, and confidence of the Airborne transformed a common soldier to one of the elite fighting men of the world. In addition to this military designation, Kentuck earned his wings, achieving the unachievable goal of his childhood.

Upon graduation, he left Fort Bragg, North Carolina. Kentuck carried orders becoming an All American, a member of the 82nd Airborne Division. Best yet, he was a replacement for a unit based in Japan. His Airborne buddies felt fortunate because exotic Japan seemed fantastic. Many of the married men planned to bring their wives to the Japanese isles. The single men felt confident that they could find companionship and adventure in Japan. So most of the men dismissed the Korean War altogether. They imagined that if deployed to Korea, it would be for a few days. The Airborne performed some important commando raid before returning to beautiful Japan. The beautiful women of Japan provided companionship to the Airborne waiting for their next vital duty. The Airborne—the elite—performed special missions not everyday combat.

Kentuck packed to leave Fort Bragg. He stuffed his kit into a duffel bag, the serviceman’s suitcase. Dressed in his khaki Class B uniform with his “C” cap, Kentuck walked to the post depot. The cloth “C” cap, standard part of the Class “B” uniform, lay flat on a table. On the head, the hat resembled a boat. The soldiers thought that the boat-shaped hat had a look-alike in nature. So the “C” cap derived its name from a four-letter slang description of a delicate part of the female anatomy.

What a train journey from Fort Bragg! The youthful recruits rode a troop train from North Carolina to Seattle, Washington. For most, the end of the line was Korea. After the numbing boredom of training, the ride proved a wonderful respite. Twenty weeks of pay fueled the fun because nobody spent much of the money earned in training due to lack of opportunity. The young, reckless, and relatively wealthy soldiers drank, smoked, talked, and played cards all the way across the country.

During the day, the old sergeants craned to the right and left, viewing the sights while the young privates snored, oblivious to the passing scene. At noon, the whole car of catatonic privates appeared as if every soft head had been struck with a wooden mallet. At night, the old sergeants retired while the privates partied. Though several fights erupted in this bawdy environment, no one was disciplined during the trip. No one was going to prevent a soldier from doing his duty over a minor slugfest. Even the pugilists didn’t hold a grudge for more than an hour. On that train, Kentuck’s company lived like lords.

When Kentuck exited the train in Seattle he felt horrible. His twenty-eight weeks of clean living softened Kentuck for five days and nights of nonstop partying on the train. Kentuck suffered from a terrible hangover; his aching body longed for sleep, his lungs choked full of smoke, his irritated eyes delirious, and his mind exploded. But those woes soon disappeared like shadows in the bright lights of Seattle. Immediately, Kentuck longed to explore the enormous Emerald City.

A six-hour pass was granted to each soldier. Before sailing overseas, the men received liberty for fantasy night in the Emerald City. Upon receiving a pass, Kentuck and two fellow soldiers walked to the waterfront. Staff Sergeant Brooks sought women. Kentuck’s other companion, Corporal Riley, demanded beer. The intrepid trio discovered Lana’s, a dive. In Lana’s, both of Kentuck’s companions fulfilled their objective.

Lana’s featured dancing girls. Kentuck had a preconceived mental image of the dancing girl. In his mind, he saw Veronica Lake. Unfortunately, the dancers of Lana’s resembled the Great Lakes. The bawdy, unattractive women, the soldiers, and intrepid locals enjoyed the wild scene. The dingy place overflowed with soldiers who escaped Mama, the church, and their hometown officials for the first time in their lives. Drinking was the order of the day.

Kentuck’s pass expired at eleven p.m., but eleven came and went with the stalwart revelers occupying barstools. Finally, Kentuck urged his mates to leave, fearing the inevitable trouble. A few minutes after leaving the bar, trouble arrived in a jeep. The MPs swept the streets, looking for late soldiers. Kentuck was arrested.

A night in the stockade dulled all enthusiasm for the Emerald City. Orders came the next morning to report to the commanding officer. The three infantrymen were as meek and shy as newly shorn sheep. Worry accompanied the three defendants as they slunk into the office of the CO (“Commanding Officer”). Anything could happen and most options were bad. The two sheepish NCOs (“Non-Commissioned Officers”) feared losing a stripe. Having only one stripe of the Private First Class on his sleeve, Kentuck didn’t have much to lose. Yet that stripe cost intense effort and he dreaded losing it.

The old colonel thoroughly explained the cause of his irritation. Quickly, the listeners gained an enlightened point of view. After the preaching phase of their trial ended with a stony glare, the dreaded punishment phase of their trial commenced.

“You men are due to ship out today for the East?” asked the colonel, his eyes hard.

“Yes, sir,” explained Riley, “I am going to Korea. I’m supposed to fight. I want to fight, sir.” This was the truth as Riley was a regular infantry and not a member of an elite Airborne unit like Kentuck. The argument bumbled from his lips, void of falsehood and powerful in logic. Perry Mason could not have done better. The argument proved a winner.

“I don’t want to hear of this type of behavior ever again. As punishment I am going to confine you men to the ship for a period of fourteen days! Dismissed.”

Guilty of tardiness, the banditos hustled from the office. Not being penitent in the least, the men laughed at their punishment. Since the ship would be at sea anyway, neither the guilty nor the innocent could leave the ship for fourteen days; unless it sank. Despite being hung over, the men rapidly ran to the barracks and grabbed their gear. Kentuck couldn’t have been less prepared for the twenty-one-day ocean voyage that awaited him.

In Seattle, Kentuck boarded the General Migs, a troop carrier under the American flag. Kentuck, a landlubber, had never sailed before. Five hundred men crammed into a single compartment like cattle. Their bunks were five tiers high. Kentuck found a bunk at the third level. Too late, Kentuck discovered the fifth level was best. The reason was that the landlubbers invariably become sick with the constant rolling of the sea. Following seasickness was vomit. It was difficult to determine who suffered more: those who had been plow jockeys or the streetcar riders. From the first hour after departure for San Francisco until Kentuck landed in Pusan, he was sick as the old dog. Kentuck heaved daily and so did many others. The bottom level of the five-tier bunk was the landing zone for the spray.

Another reason the fifth bunk proved advantageous was that the soldiers climbed to and from their bunks. The guy on the bottom bunk lay with the footprints of four soldiers on his bunk. The foul stench of soldiers’ feet permeated the first bunk, curling the stoutest nose. It is fortunate that my writing and your imagination cannot capture the stench in those cramped quarters after a twenty-one-day puke convention of the U.S. Army’s newest overseas privates.

Kentuck’s seasickness temporarily subsided under the Golden Gate Bridge. The ship docked on the wharf of San Francisco, and no one was permitted to leave the General Migs. Beautiful San Francisco was admired from a distance. For a short time the ship did not toss around like a bubble in the bathtub. In San Francisco, more troops piled on board and the throng sailed away. The ship changed from crowded to jam-packed.

The ship left the harbor, steaming into the Pacific Ocean for the long voyage. The great ocean filled the horizon in all directions with tormenting waves. After several hours on the ocean, Kentuck’s seasickness was worse than ever. Every swell tossed the ship, and the close quarters and general discomfort only increased the misery. The night brought little comfort. Each soldier retired, sleeping in the surreal world inside a metal ship with eerie emergency lamps providing the only light.

Days later, when every moment became unbearable on the high seas, the captain announced a delay due to a naval emergency. A cargo freighter crewmember fell down a flight of stairs, fracturing his skull. The freighter lacked medical staff. The General Migs, with its trained doctors, sailed south to rendezvous with the freighter. The experienced medical staff sought to save the unfortunate accident victim. The seamen, known to the soldiers as “swabbies,” carried this poor fellow aboard. Unfortunately, despite the altruistic efforts, the poor fellow died during his first night on the General Migs. The seamen stowed the body. The green soldiers resumed their undulating voyage, bouncing their way to the Orient.

Kentuck’s seasickness did not kill him, but at times he longed for sweet death. Kentuck lost weight, patience, and, quite often, his temper. The edgy soldiers raged to fight. The Army couldn’t wait to face the flamethrowers, mortars, artillery, and the red devils. Anything seemed preferable to spending another moment on that floating torture chamber.

Unbelievably, the Navy intentionally worsened the trip. The captain decided areas of the ship needed a paint job. As the ship rolled in the ocean, the crew renovated. Sailors manning jackhammers chipped old rust and oxidized paint from the side of the superstructure of the General Migs. This created an agonizing noise for the inhabitants of the metal can in no mood to endure it. It sounded like men beating on a steel helmet with hammers. All the while, the soldiers wore the steel helmet. The soldiers yelled at the swabbies to knock off the noise. The sailors laughed and told the soldiers where to go. Swabbies have no mercy for soldiers.

After several days, the grinding stomachs, the clanging of metal on metal coupled with the unrelenting mirth of the sailors battered the pride of the soldiers. This brought the army to revolt. The soldiers snatched their revenge. While the swabbies dined in the mess hall, a couple of Airborne soldiers repelled down the ropes to the platform hanging on the side of the superstructure of the ship. These rebellious soldiers threw the jackhammers into Davy Jones’s locker. To the annoyance of the swabbies, they couldn’t torture the soldiers any more.

The ship didn’t allow any moment for peace or contemplation. Even the toilets,—”heads” on a ship—were strung along both walls without stalls. Invariably when Kentuck sat on the thunder mug, some sailor would sit opposite of him and converse.

“Wheeeeeeeerrreeee yyaaaaaaa frooooooooooommmmmmmm?” grunted the swabbie while Kentuck would have preferred quiet.

After many miserable days the Nippon Islands appeared at last, and Kentuck’s company docked at Yokohama, Japan. How the afflicted soldiers longed for that day. Then the ugly head of merciless Fate intervened. For some mysterious reason, no one was permitted to leave the ship. Fifteen hundred guys were prohibited from disembarking for fun in Japan. Instead, orders demanded their transportation directly to Korea. The democracy needed brute force now.

This caused a great wave of angry complaints. The married men who promised their wives a life in Japan could no longer provide it. The single men who planned adventure in cosmopolitan Japan would not see any. The severely seasick, like Kentuck, faced an extended stomach-turning cruise. Instead of merrymaking in the Japanese Isles, the scorched earth of Korea awaited these knights of freedom. The only person who stayed in Yokohama was the dead merchant marine. The only reason the Navy even stopped in the promised Japanese Islands was to deposit the corpse. This unfortunate fellow had lengthened the misery of thousands by his untimely accident, but he paid the ultimate price for it. The swabbies carried his dead body into Japan, and the disappointed soldiers returned into the ever-undulating sea.

A short time later, Kentuck’s company steamed into the harbor of Pusan, Korea. The sky was dark and the sea was darker still. Kentuck stood on weak legs as he peered at the crowded, dirty city filled with refugees. He heard the thunder of the big guns many miles away. Something made him think of the story of Icarus and Daedalus. For many years, Kentuck had thought Icarus was supremely stupid. Kentuck was determined to model his life after the wise Daedalus and succeed. Now, Kentuck remembered that he had disobeyed the admonitions of his father. For the first time, he realized that he no longer had his wings and before him was the abyss.