Читать книгу Preacher - David H. C. Read - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеPreacher

I have stood toe to toe with cheering Spaniards and Italians as Pope Paul was carried into St. Peter’s on a throne for a Sunday Mass. I have gazed with wonder at the lofty Gothic architecture of New York’s Riverside Church and Dr. Coffin at his eloquent preacherly best. I have seen Jimmy Swaggart cry on television.

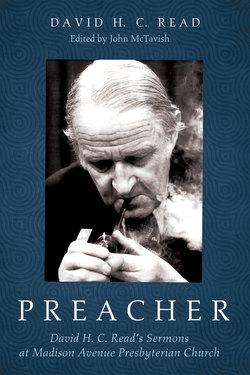

Striking experiences all. But the preacher who has most nourished my soul and stimulated my mind over the years has been a Scottish import by the name of David H. C. Read. From 1956 to 1989 Dr. Read was the pastor of New York’s Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church. For twenty-five of those years he was also a regular preacher on NBC’s National Radio Pulpit. He had his own weekly Sunday program on WOT-AM radio entitled “Thinking It Over” and he published over thirty books, which included some of the only collections of sermons that major publishing firms such as Eerdmans and Harper and Row have ever dared to cast into print. All in all, a modern day prince of the pulpit, if there ever was one.

Yet search the internet for the names of great modern day preachers and Read’s name is not likely to appear. Instead we get names like Billy Graham, John Stott, and Joel Osteen representing the evangelical side, and Fred Craddock, William Sloane Coffin, and Barbara Brown Taylor carrying the torch for the liberals. Inspiring preachers all, but no mention of David Read.

Why?

Perhaps the minister from Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church was too much of a theological centrist to enjoy what passes in ecclesiastical circles as a fan club. The crowds tend to gravitate to simplistic extremes if only because the extremes give the impression of radicalism and rigor. Yet surely the true radical is the person who gets to the radix, or “root,” of things. This in any event is what Read’s preaching does, displaying a combination of theological discernment and literary charm that puts this preacher pretty much in a homiletical class by himself. Who was this man, what made him tick, and what can we learn from his powerful proclamation of the Gospel?

David H. C. Read was born in 1910 and grew up in Edinburgh, where he attended the Church of Scotland with his family. He flirted briefly with agnosticism, but then one day a high school friend invited him to attend a popular evangelical summer camp. There, in the magnificent countryside of the Scottish Highlands, Read enjoyed games, expeditions, concerts, songs, and a spiritual awakening. The camp teemed with university students and young professionals who spoke of Christ as a real person whom one could get to know in a deep and intimate way. David Read accepted the message and became, as he tells us in his autobiography This Grace Given, “if not a dyed-in-the-wool fundamentalist, at least a fervid evangelical ready to do battle for the faith.”

Even so, the young convert couldn’t help noticing that the camp leaders often applied psychological pressure on the campers to make decisions for Christ. They condemned the worldliness of smoking and dancing while spending lavish sums on sports cars and fancy clothes, and railed against issues of personal immorality while saying nothing about the crushing economic issues that many were facing in those early years of the Depression. Worst of all, they blithely ignored the fire-breathing madman who had recently emerged in Germany. Still, these were the people who had given David Read the pearl of great price, the incomparable gift of the Gospel, and for that he remained thankful.

After graduating from high school, Read enrolled in an Honors English course at the University of Edinburgh. He now began juggling the world of Shakespeare and Milton with soccer on Saturdays and worship services on Sundays. He continued attending the local parish of the Church of Scotland with his family, but on Sunday evenings he often made the round of churches, imbibing the pulpit eloquence of such Edinburgh greats as James Black, James Stewart, and George Macleod.

Read also enjoyed listening occasionally to Graham Scroggie, a Baptist minister who delivered expository sermons in a rather dry but straightforward and no-nonsense way. One Sunday evening he went to hear this fellow Scroggie preach, only to learn that the minister had been called away for the weekend and a substitute stood in his place. Read considered leaving, but at the last minute he decided to stay and hear what the substitute had to say. The experience proved life-changing. As he recalls in his memoirs: “I remember neither the preacher’s name nor anything he said. What I do remember, with luminous clarity, was that in the middle of the sermon I was suddenly and totally convinced that God wanted me to be a minister.” Never before or after did David Read experience such an overpowering sense of the divine summons. Make of this moment what one will, but that night the bright young university student went home and quietly resolved to become a minister.

After gaining his degree in English, graduating summa cum laude, Read began making plans to study theology at New College, the Edinburgh-based seminary of the Church of Scotland. (He had come to realize that, for all his concern that a theological liberalism might amount to “little more than agnosticism with a halo,” the Church of Scotland was still basically his spiritual home.) But then the budding young theologian learned that New College was offering a scholarship which would allow him to study theology at the three seminaries—Montpellier, Strasbourg, and Paris—of the French Protestant Church. This was even better. Read immediately contacted the donor of the scholarship, and gained the coveted opportunity to begin his theological studies in Montpellier, France.

A transforming learning experience soon occurred when Pierre Maury came to the Montpellier seminary to conduct a retreat. The dynamic Maury, on his way to becoming one of France’s greatest preachers, was known to be a disciple of Karl Barth, and in fact was coming from Bonn where he had been studying under the great Reformed theologian. The impact that Maury had upon Read was both profound and lasting. Read had been clinging to the theology of the evangelicals as a refuge from the theological wasteland of a liberalism that seemed to reduce the gospel to little more than what Matthew Arnold once called “morality tinged with emotion.” But now here was Maury and behind him, as Read notes in This Grace Given:

“ . . . the magnetic figure of Barth—two men who spoke of God in all his glory with a far greater power than the fundamentalists (whose God tended to be as narrow as the range of their own imaginations); who spoke of God’s Word in language so dynamic that it shattered my previous concept of the Bible as a code-book of doctrines and morals plus a few stories and passages of dramatic power; who lifted up Christ in his incarnation, death, and resurrection as the unique Savior and Lord of a fallen world; and who obviously were able to accept the critical view of the Scriptures not grudgingly but joyfully, as a sign of the true humanity through which God speaks.” (p. 56)

This did not mean that David Read now became a slavish Barthian. On the contrary, as he tells us in his memoirs, he gratefully appropriated insights over the years from Catholic theologians such as Karl Rahner and Hans Kung, from philosophically-oriented theologians such as John Baillie and Reinhold Niebuhr, and even from Paul Tillich, “not to mention Dietrich Bonhoeffer.” Still, as far as the young man from Edinburgh was concerned, Karl Barth remained “the theologian of the twentieth century.”

Barth’s name calls to mind an amusing incident that I witnessed during one of Read’s post-Christmas preaching seminars at Princeton Theological Seminary. A number of us in the class had joined him for supper one evening at the college cafeteria. In turn we were joined by a talkative young seminarian who, upon discovering that we were all ministers, volunteered for our edification Paul Tillich’s comment according to which preachers should stand in the pulpit with the Bible in one hand and the daily newspaper in the other. There was a brief pause, and then Read gently corrected the student: “I think it was Barth who gave us that choice bon mot.” “Oh no,” said the student full of confidence, “it was Tillich all right.” At which point Read smiled mischievously and said, “No, no . . . Tillich was the theologian who encouraged preachers to stand in the pulpit with the Bible in one hand . . . and a copy of Playboy in the other.”

But to return to our story: Before David Read completed his formal theological education in Scotland, he went on to study in Paris and Strasburg. He also enjoyed a semester along the way in Marburg, Germany, studying with Rudolf Bultmann. Read had actually wanted to study under Barth in Bonn, but the Principal of New College, “a strong liberal,” ordered him to go to Marburg so that he could imbibe the wisdom of the New Testament scholar and subsequent advocate of demythologization. The young Scot’s theological horizons were consequentially widened under Bultmann’s challenging interpretations, but not at the expense of diluting the Christological heart of the gospel.

In the spring of 1936, David Read was ordained. That same year he married Pat Gilbert and began his ministry with the Presbyterian Church in a small, quiet town on the Scottish border. All of this might well have been idyllic except for the storm clouds that were gathering in Germany. Many in Britain ignored these clouds if only because they couldn’t bear the thought of another war with the memories of the last one still so painfully fresh. But Read took the signals to heart, remembering perhaps the rising militant fanaticism that he had witnessed during his semester in Marburg. He had actually been arrested that year and hauled off to the commandant’s office by an S. A. guard for taking pictures of Nazi officials. In his defence he claimed that he thought that the Stormtroopers were a perfectly harmless group like the Boy Scouts. However, it was probably only on account of his British passport, and the fact that the Nazis had been instructed to be polite to British and American visitors, that Read escaped imprisonment. Returning to his residence he couldn’t help reflecting, he tells us in his memoirs, on how different things might have been had he been a German, let alone a Jew.

When Britain declared war with Germany on September 3, 1939, David Read volunteered as a military chaplain and was soon working at a hospital in Le Havre where he experienced the period of the so-called “Phony War.” Western France in fact was so quiet that fall and winter that Read finally requested a transfer to another division on the Belgian border. Again, things were very quiet for several more weeks. But then, in the spring of 1940, Germany struck and suddenly all hell broke loose.

The fledgling British troops quickly found themselves pushed back to the sea. Some of their units attempted to escape back to England, but Read’s division was trapped in a town near the sea. General Rommel now decided to concentrate on killing the British soldiers who were making for the boats and trying to escape by water. This decision probably saved the lives of the soldiers in Read’s battalion. Instead of being shot, they were taken prisoner and marched 250 miles to Germany where they spent the next five years behind barbed-wire fences.

This was the war, then, for David Read: one hair-raising, life-threatening moment after another spent almost entirely behind barbed wire. Even so, the young chaplain survived, and when the guns finally fell silent in the spring of 1945, Read was able to return to Scotland and take up his ministry afresh in a suburban church in Edinburgh. This was Greenbank Presbyterian Church which he served for the next four years (the ex-chaplain requiring the first six months, he wryly notes in his memoirs, to re-learn the accepted language of respectable society). Five years as a chaplain at the University of Edinburgh followed the suburban pastorate. Then, in 1955, Read was offered the opportunity of a lifetime—a teaching chair at St. Andrew’s University, following in the ranks of Donald Baillie and other world-famous Scottish scholars. But while he was mulling over this golden opportunity, an invitation came to leave Scotland altogether and move to America where a whole new adventure awaited him.

Here’s how it happened.

During the summer of 1955, free from his chaplaincy duties, David Read had accepted an invitation to spell off two ministers in North America on their holidays. The month of July was spent preaching at Deer Park United Church in Toronto, and catching up with a number of Canadian cousins. Then in August, Read went to New York to occupy the pulpit at Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church where, even on sweltering summer Sundays, over a thousand worshippers normally formed the congregation.

That first weekend in the Big Apple proved especially dramatic. It began with Read and his wife Pat arriving in Manhattan on the first Saturday of August and settling into a small apartment that a friend had loaned them for the month. Their first night in New York was spent enjoying a Broadway play. Alas, when the young couple got back to their residence they discovered that they had left their only key inside the apartment. Every trick in the book now failed to gain them entrance into the flat, and they ended up going to a hotel for the evening.

But no sooner had they settled down to sleep than Read realized that the flat held not only his luggage and church robes, but a copy of the sermon that he planned to preach the next morning. The distraught preacher simply had to get back to the flat even if it was well past midnight. He accordingly called the police who came around and tried to find an extra key by waking up the neighbours in the apartment building. When this strategy proved fruitless (not to say, in some cases, offensive), Pat Read came up with the bright idea of calling the chauffeur of the woman who had lent them the apartment. Success! The key at last was retrieved and the Reads were finally able to get into their flat.

Only now it was almost morning. There was barely time for a couple hours of sleep before the exhausted couple had to get up and dash off to the service at Fifth Avenue. So it was that, with croaky voice and bleary eyes, David Read preached what was surely the most consequential sermon in his lifetime. For though he didn’t know it at the time, a number of key people from Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church were sitting in the pews at Fifth Avenue that day. In the wake of George Buttrick’s recently announced retirement they were looking for a new minister, and this was the unsuspecting preacher’s opportunity to win their hearts. Their hearts, needless to say, were captured. And before the month was out Read had accepted their invitation to leave his homeland and the promise of academia, and embark upon a whole new adventure in his life and work.

Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church proved a marvellous fit for this gifted but unassuming Scot. The sanctuary itself was modest in size, at least by Manhattan standards, and designed, as Read gratefully notes in Grace Thus Far, not as an auditorium dominated by a pulpit, but as a place to worship. The congregation’s community-oriented philosophy and egalitarian working relationship amongst the staff also appealed to Read’s interest in serving the various needs of a fully rounded congregation and not playing the role of a pulpit star. In 1956, then, the Scottish implant became the minister of Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church, and ended up serving the congregation for thirty-three years, retiring in 1989, at a still vigorous eighty years of age.

Throughout his career, David Read never comported himself as a pulpit star or ministerial big shot. He liked in fact to tell the story of the inflated preacher who says to the secretary, “Tell that nuisance to go to hell—I’m composing a masterpiece on Christian love.” That Read never screamed at people is something to which I can personally attest. I once drove him to the airport in Toronto after a preaching seminar in nearby Hamilton. Plying him with questions, I shot right past the exit for the airport. For a few tense moments it looked like my pulpit hero might miss his flight back to New York. Read’s voice, as I recall, grew a bit testy, but he didn’t scream. Fortunately, he didn’t miss his flight either.

In the preaching seminar that I mentioned earlier, Read encouraged us to play a tape of one of our recent sermons. The group then discussed each sermon in turn. Our comments were largely appreciative, especially at first. But as the seminar wore on, we became more and more critical of each other’s efforts. In fact at one point, I suddenly realized to my chagrin that Read’s voice was the only unreservedly positive one in the room. The rest of us had forgotten, it seemed, his introductory remarks in which he had stressed that preaching is not a competition but a response to Christ’s call: “Go and proclaim the kingdom of God.” It doesn’t matter, Read said, whether we respond to the call with one talent, two talents, or ten. The important thing is to respond, and thus share the good news with whatever talents the Lord has given us.

On the final day of the seminar Read played a tape of the Christmas fantasy sermon that he had delivered on Christmas Sunday a few days earlier in his church. I well remember the hush that fell over the room at the conclusion of the recording of this sermon. No one said a word. No one murmured polite little compliments. And certainly no one offered a critique! We all just sat there kind of stunned and thinking: Ah, that’s what it means to be a ten talent preacher.

The bulk of this book features forty-one sermons by this super-talented preacher. All but one of the sermons is published for the first time beyond the in-house press of Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church. The sermons have been arranged according to the pattern of the church year, and brief introductions have been added by way of elucidating Read’s theme and style.

A list of David Read’s books that remain available today through www.abebooks.com has also been included along with some brief reviews that I have written, highlighting the contents of some of these works. Finally, David Read’s sermon Virginia Woolf Meets Charlie Brown is reprinted at the end of the book, giving the reader a taste of the kind of homiletical material that remains available through www.abebooks.com.

Ministry after David Read

After David Read retired in 1989, an interim period followed, and then Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church called the Rev. Dr. Fred Anderson to replace Dr. Read. I am sure I wasn’t the only person in the ecclesiastical world who wondered how Fred Anderson, how any minister, was going to replace a pulpit giant like Read. Recently I contacted Anderson and asked him how, in fact, he managed this feat. What Dr. Anderson told me was so moving and instructive that, with his permission, I am relaying exactly what he said:

“When the Presbytery’s Committee on Ministry approved me for membership, allowing my name to be announced to the congregation, I asked if my wife Questa and I could visit David and Pat in their new apartment the church had provided them for retirement. There were some things I needed to talk over with him. The following morning, we went to see them for coffee. We sat in their sunny dining alcove having coffee and biscuits, and exchanging pleasantries. Before long, David began to fidget. Wanting to smoke his beloved pipe, he said, ‘Fred, let’s go to my study,’ and so we did [it was the only place in the new apartment Pat would let him smoke!]. Once we were settled in the privacy of his study I said, ‘David, there are three things I need to say to you. First, few people have the opportunity to follow who they think is the very best at what they do, and that is what is happening here—you have been a preaching role model for me since I first read your sermons in Seminary. Second, you are still a Pastor at MAPC, and I expect to see you in worship on Sundays when you are in the city. It will be intimidating for a while, but I will get over it. But you need to be in worship and the people need to see you, for you are still their pastor—we can share them! Third, when they ask you to do a wedding, funeral or baptism, please direct them to me so I can invite you. You are welcome to do as many as you like, or not, but better yet, we can do them together.’ David broke into a broad grin, saying, ‘I can see we are going to get on together very well.’

“And we did. For the next several years we shared all sorts of liturgical events, he always taking one of the six lessons-sermons for the three-hour Good Friday services, vesting and reading scripture in festival services, sometimes calling on parishioners with me—he always casting his mantle over me, telling folks I had given him back his church. We even toured Scotland together one spring after Easter. It was a momentous trip. I met him in London (Pat stayed behind in London to visit her brother, Jimmy, and then went on to their new home in Majorca). We took the train north to Glasgow, rented a car and drove the countryside, retreating for three days at Iona, visiting all of his old friends from war days ranging from the captains of various industries (Forres) to Dukes and Duchesses (Argyle and Aberdeen), St. Andrews, his brother in Edinburgh, where we returned the car, and from there back to London, again by train. We rounded it out, with a wonderful few days, joining Pat and her older brother, John, at the Read’s retirement home in Majorca.

“In the first few years of retirement David was a bit lost—as first years of retirement often seem to go for pastors. After re-reading all of his P.G. Woodhouse books, he fell into a bit of a depression, and I encouraged him to write another book. He agreed and began making a few notes. But as was his practice with sermons, he really couldn’t get into the swing of things with his writing until he had crafted a title. Then one day, a year or so later, he called me on the phone and said, ‘Fred, I’ve got it. What do you think of God Was in the Laughter?’ ‘It is perfect,’ I told him. He began to write, and I began looking for someone to help with the type-script and then finding someone to publish it, as most of his older publishing connections were gone. The book includes David’s reflections on his own impending death, and it is classic David Read! Shortly after finishing the book, he fell into physical decline, becoming homebound. We celebrated his 91st birthday, January 2, 2001, with a few close friends from the church. Five days later, I celebrated communion with him and Pat and two elders in their apartment at his bedside. He died peacefully, later that night.”

N.B. God Was in the Laughter is published in conjunction with David Read’s earlier autobiographical works: This Grace Given and Grace Thus Far (cf. p. 273).

Please also note: A CD recording of David Read preaching on three memorable occasions is available. Contact John McTavish for information (jmctav@vianet.ca).