Читать книгу The Villa of Mysteries - David Hewson - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление‘How long has she been lying there? Answer me that.’

Teresa Lupo stood next to the brown cadaver that lay at a stiff, awkward angle on the shiny steel table in the morgue. The pathologist looked even more proprietorial than usual about the corpse in her care, and immensely pleased with herself too. It was two weeks now since Nic Costa and Gianni Peroni had encountered the body and the screaming American couple by the muddy banks of the Tiber, just a couple of kilometres from the sea at Ostia. Bobby and Lianne Dexter were back home in Washington State, talking to lawyers about their divorce and who should have custody of the cats, still feeling lucky to have escaped Europe without facing a single charge (which proved, Lianne thought, exactly what kind of people they were over there anyway). Costa and Peroni had, in the mean time, become, if not quite a team, partners of a kind, able to get through the day with a sense of shared duty and the promise that soon their artificial relationship would be over.

The body had made international headlines for a few days. Somehow a photo had been smuggled to the media, showing the serene, frozen face that had emerged from the chemical-smelling peat. It was a genuine mystery. No one knew how old the body was. No one knew whether the girl had died of natural causes or was the victim of some obscure crime. There was wild speculation in some of the Italian tabloids, stories which talked about ancient cults that had killed followers who had somehow failed the entry ceremony.

Nic Costa hadn’t taken any notice. It was pointless to speculate until Teresa Lupo had passed judgement. Now she had made up her mind. They had been summoned to the morgue for ten that morning. At noon Teresa planned to give a press conference outlining her findings. The very fact she’d arranged this herself without asking advance permission from Leo Falcone spoke volumes. It meant she was confident there was no criminal investigation on the way. He and Peroni had simply been invited along out of politeness. They found the specimen; they deserved to hear its secrets revealed. Costa wished Teresa had left them out of it. He was starting to get the feel for police business again, starting to like the idea he could be good at it. If this really was a closed case, he’d rather be somewhere else, dealing with a live one.

The three of them – Falcone, Peroni and Costa – sat on a cold, hard bench watching her make a few last-minute, fussy observations of the corpse. Costa understood what this was: a dry run for the press conference which would be part of her re-entry into police life. Teresa Lupo had briefly quit her job after the Denney case, vowing never to return. She had been close to Luca Rossi and felt the pain of his death as much as anyone in the station. More, perhaps, than Nic Costa. More certainly than Falcone who, while quietly racked by guilt over the loss of his man, was too obsessed by the job to be distracted for long.

Grief chased her from the tight, close embrace of the force. Grief brought her back to the fold. She was like the rest of them: hooked, incapable of staying away. She loved getting to know her customers, trying to understand their lives and what had brought them to her slab. Unravelling these mysteries fulfilled her and now she was starting to show it, Costa thought. She was carrying a little less weight. The ponytail had gone, replaced by a businesswoman’s crop, black hair short and sculpted carefully to hide the outline of her heavy neck. She had a large, animated face and slightly bulbous blue eyes that darted around constantly. There was something a touch obsessive inside the woman, something that quickly chased away most men who tried to get close to her. Maybe that was what made her the pathologist the cops always wanted on their side, however fierce her temper, however sharp her tongue …

‘Ten years. Twenty max,’ Peroni suggested. ‘But what do I know? I’m just a busted vice cop. You got to bear the responsibility for any screw-ups I make, Leo. I’m used to dealing with people I know are guilty from the outset. All this detection stuff … it’s not my thing.’

Falcone put a hand to his ear. ‘Excuse me?’

‘Sir,’ Peroni said meekly. ‘You got to bear the responsibility, Sir.’

Falcone sat there in a grey suit that looked as if it were new that morning, letting his fingers run through his angular, sharp-pointed silver beard, staring at the body, thinking. He’d returned from a holiday somewhere hot only the day before. A deep walnut tan stained his face and his bald scalp. It was almost the colour of the corpse on the slab. The inspector seemed miles away. Maybe his head was still on the beach, or wherever he went for enjoyment. Maybe he’d been through the force disposition. There was a flu epidemic gripping the city. People were calling in sick from everywhere. The Questura had so many empty desks that morning it looked like Christmas Day.

Teresa was grinning. Peroni had said exactly what she wanted to hear. ‘That’s a good and sensible suggestion, even for a busted vice cop. Your basis for it being …?’

He waved his hand at the table. ‘Look at her. She’s a touch messed up but she don’t stink too bad. Nothing going mouldy. I’m sure you people have seen worse. Smelled much worse too probably.’

She nodded. ‘The smell’s from the treatment. She’s been lying in a shower ever since we got her here. Fifteen per cent polyethylene glycol in distilled water. I’ve been doing a lot of research on this girl. Reading books. Talking to people. I’m in touch with some academics in England by e-mail who know exactly how to handle a body in this condition. After ten weeks or so maybe we’ll need to get her freeze-dried to finish the job properly.’

‘Don’t we get to bury her in the end?’ Costa wondered. ‘Isn’t that what you’re supposed to do with dead people?’

She screwed up her big pale face in amazement. ‘Are you kidding me? Do you think the university would allow it?’

‘Since when did she belong to them?’ he asked. ‘However old she is, she was a human being. If this isn’t going to become a crime investigation, what’s the problem? When does a corpse turn into a specimen? Who decides?’

‘I do,’ Falcone said, coming out of the daydream abruptly. Costa peered at him. There was something odd going on. Falcone wasn’t as cool, as self-composed as normal. He looked glum, which was unusual. It was rare that anyone was able to discern much sign of human emotion in him at all. Costa wondered who Falcone had been on holiday with. The dour inspector’s marriage had ended years ago. There were rumours of occasional attachments since then but that could just be station gossip. When Leo Falcone was in the Questura nothing else seemed to exist except the force. When he was gone, he was out of it completely, never mixing with his colleagues, never wanting to be invited round for dinner. Maybe the inspector, who always seemed so calm, so in control when it came to other people’s lives, had no hold whatsoever on his own. Maybe he went on holiday by himself, sitting on some sunny beach somewhere reading a book like a hermit, turning browner and browner, meaner and meaner.

‘Hear me out,’ Teresa pleaded. ‘It’ll all become clear, I promise. A couple of decades? Nice guess. But I have to tell you it’s out. By a touch under two thousand years.’

Peroni snorted. ‘Someone’s been hitting the wacky baccy around here, Leo. Excuse me. Sir. How else can you come up with that kind of shit?’

‘Wait for it, wait for it,’ she demanded, waving a finger at him. ‘I can’t be precise, not yet, but I hope to give you something pretty accurate very soon. This body’s been in peat all that time. From the moment you put a corpse in that kind of bog it starts getting preserved. Sort of a mixture between mummification and tanning, and completely unpredictable too. Plus, there’s no end of industrial effluent getting poured into the river out there and God knows what that does. I got parts of her almost as hard as wood, other areas soft, almost pliable. Haven’t even contemplated a conventional autopsy – for reasons that will shortly become obvious – so God knows what kind of state she’s in internally. But I have a date. Peat plays havoc with normal radiocarbon dating techniques. I won’t get technical on you. Let’s just say the acid in the water depletes just about anything we can use for a radiocarbon test. There are things we can try, like getting some cholesterol out of her, since that’s virtually immune to long-term soaking. But right now I’m working with some organic material from the dirt beneath her fingernails. And that’s somewhere between 50 AD and 230 AD.’

They just stared at her.

‘Is that really possible?’ Falcone asked eventually.

She went over to the desk and picked up a large brown envelope next to the computer. ‘You bet. None of this is new. The archaeologists have a term for it. “Peat bodies”. They’ve been there for centuries but no one noticed until companies started digging up the bogs for the gardening business. The area behind Fiumicino was never big enough to work commercially. Mind you, there’s been a lot of rain this winter. Maybe that took off some of the surface soil and made it easier to find.’

She crossed the room and passed them a set of colour photographs. They were of corpses, brown corpses, some contorted, half shrunken, half mummified, a little more exaggerated than the one now on the slab but recognizably similar all the same.

‘See this one,’ she said, pointing at the first picture. It was the head of a man, apparently turned to leather. The features were almost perfectly preserved. He had a calm, composed face. His eyes were closed as if in sleep. He wore some kind of rough leather cap, the stitching still visible on the crude seams. ‘Tollund, Denmark. Found in 1950. Don’t be fooled by the expression. He had a rope around his neck. Executed for some reason. Some good radiocarbon material there. Puts his death somewhere over two thousand years ago. And this—’

The next picture was of a full corpse: a man, reclining on what looked like rock. He was more shrivelled this time, with his neck turned at an awkward angle and a head of matted red hair.

‘Grauballe, also in Denmark, not far away, though he’s even older, third century BC. This one had his throat cut ear to ear. They found traces of the ergot fungus – the magic mushroom – in his gut. It’s not easy to recreate what went on but there’s a common theme. These people died violently, maybe as part of some ritual. Drugs tended to be involved. Here—’

She began scattering pictures over their laps, corpse after mummified corpse, many crouched in that tortured, agonized position any cop who’d visited a modern murder scene already knew too well. ‘Yde Girl, in Holland, stabbed and strangled. She was maybe sixteen. Lindow Man, England. Beaten, strangled then dumped in the bog. Daetgen Man, Germany. Beaten, stabbed and beheaded. Borremose Woman, found in Denmark, face caved in, probably by a hammer or a pickaxe. These were all people in primitive, pagan agrarian societies. Maybe they did something wrong. Maybe there was some kind of sacrificial rite. Peat bogs often had a kind of spiritual significance for these tribes. Perhaps these were offerings to the bog god or someone. I don’t know.’

Falcone put down the photos. He seemed remarkably uninterested in them. ‘I don’t care what happened in Denmark a couple of millennia ago. What happened here? How, specifically, did she die?’

She didn’t like that. Teresa Lupo had been expecting a little more credit for what she’d found out, Costa thought. She deserved it too.

‘Listen,’ she answered sharply. ‘We have limited resources. Like Nic said, when do we have a body and when do we have a specimen? I can make that judgement for myself, thanks. This is a very old corpse. I’m a criminal pathologist, not a historian. There are people who can perform a full autopsy on this girl and the rest. It’s not a job for us.’

‘How did she die?’ Falcone repeated.

She looked at the frozen, leathery face. Teresa Lupo always felt some sympathy for her customers. Even when they’d expired a couple of thousand years ago.

‘Like the rest. Badly. Is that what you wanted to know?’

‘Usually, it’s the first thing we need to know,’ Falcone said.

‘Usually,’ she agreed. Then she gestured at the cadaver on the shining table. ‘Does this look usual to you?’

There were times when Emilio Neri thought himself a fool for hanging on to the house in the Via Giulia. He’d taken on the property thirty years before, in return for an unpaid debt from some dumb banker who’d got in over his head gambling. Neri, then a rising capo in the Rome mobs, reluctantly became the owner. He’d rather have driven the yo-yo into the countryside somewhere and put his eyes out before dropping him in a ditch. But this all happened at a time when his actions were circumscribed by others. It would be a further ten years before Neri became don in his own right, giving him the sway to order executions directly, and take a cut of every transaction running through the family’s books. By then the banker was back in business and never made the mistake of getting into his debt again, much to Neri’s disappointment.

In the 1970s the Via Giulia was still pretty much a local area for everyday Romans, not the chic street for rich foreigners and antique dealers it was to become. Created in the sixteenth century by Bramante for Pope Julius II, it ran parallel to the river, set some way below the level of the busy waterside road, and was originally intended to be a grand entrance to the Vatican, by the bridge to the Castel Sant’Angelo. The market of the Campo dei Fiori was no more than a two-minute walk away. Trastevere was maybe a minute more, crossing over the medieval footbridge of the Ponte Sisto. On a fine summer evening Neri used to make that walk regularly, pausing in the middle of the bridge to look along the river towards the vast, sunlit dome of St Peter’s. He was never much interested in views but this one pleased him somehow. Perhaps that was why he held on to the house, although by now he could afford just about any property in Rome, and was beginning to acquire a portfolio that would include homes in New York, Tuscany, Colombia and two country estates in his native Sicily.

The walk to Trastevere took him out of himself for a while. The restaurants were good too, which was something Neri could never resist. Until he was fifty he’d been relatively fit, a big, powerful, muscular man who could impose his will by force and brute physical violence if need be. Then the food and the wine took hold. Now he was sixty-five and carrying way too much weight. He looked at himself in the mirror sometimes and wondered whether there was anything to be done. Then he remembered who he was and knew it didn’t matter. He had all the money a man could want. He had a beautiful young wife who did anything he pleased, and was smart enough to look the other way if he felt like the occasional distraction. Maybe he was fat. Maybe he wheezed now and again, and had halitosis so bad he popped mints into his large, grey-lipped mouth the way some of his underlings sucked on cigarettes. Who cared? He was Emilio Neri, a don to be feared in Rome and beyond. He had influence. He had hard cash pouring into his offshore accounts, from prostitution, drug trafficking, money laundering, arms and any number of semi-legitimate investments. He didn’t care what he looked like, what he smelt like. That was their problems.

In all this pampered life there was just one minor sore and, to Neri’s occasional annoyance, it lived downstairs, one floor above the six servants he employed needlessly, just to fill up the space and dust things before they ever got dusty. While he and Adele occupied the top two storeys of the house – and had sole use of the vast terrace, with its palm trees and fountains – his only son, Mickey, had, after three fraught years pissing off Neri’s friends in the States, come home to stay. It was a temporary arrangement. Neri wanted to keep an eye on the boy just to make sure he didn’t start messing up with dope again. Once he’d found some kind of even keel, Neri would cut him loose. Maybe find him an apartment somewhere else in the city, or move him on to Sicily where there were relatives who could keep him in check. Neri did this partly out of self-interest – Mickey had grown up inside the organization. He could cause some harm if he started blabbing to the wrong people. But there was a degree of paternal loyalty there too. Mickey was an asshole. Maybe he inherited this from his mother, an over-tanned American bit-part actress Neri had met through a crooked producer he knew when he was pumping hot money into a Fellini movie. The marriage had lasted five years, after which Neri knew he either had to divorce the bitch or kill her. She now basked in the permasun of Florida and doubtless bore a close physical resemblance to an iguana, a creature, Neri thought, which could probably out-think her in its sleep.

Mickey never wanted to be near mamma. Mickey wanted to hang around his old man. He thought he was a don in the making and never missed an opportunity to throw his weight around. He had problems with women too, just couldn’t leave them alone, whether they were married or not. His one saving grace was that he worshipped his father. Everyone else, Adele included, did Neri’s bidding out of fear. Mickey went along with everything his old man decreed for a simpler reason. Most kids idolized their fathers until they were seven or eight, and then started to see them for what they were. The scales had never fallen from Mickey’s eyes. There was some undying adulation stuck fast in his genes and Emilio Neri found it strangely touching. It led him to do crazy things, such as letting the kid wander around the house whenever he felt like it, even though he and Adele, who, at thirty-three, was just one year older, loathed the sight of one another. It led him to overlook the problems that came when Mickey got a little too close to the drugs and the booze, problems that were, on occasion, expensive to fix.

Sometimes Emilio wondered who was indulging whom. Since Mickey moved in, he’d begun to wonder that a lot.

It was now mid-morning and the two of them had been bitching at each other, on and off, since breakfast. Adele half reclined on the sofa, still in her mauve silk pyjamas, face in a fashion house catalogue. Emilio thought she looked gorgeous but he knew it was a matter of taste. She was sipping a spremuta of blood-red orange juice which was almost the colour of her expensively cut hair. She sent out one of the servants to buy these things by the kilo from the market then watched as Nadia, the sullen cook she’d picked herself, squeezed them in the kitchen. Adele almost lived off the stuff. It drove Mickey crazy. Maybe it was why she was so skinny, he said. He bugged his old man about that constantly. Why marry some redhead with the figure of a pencil when you could have just about any woman in Rome?

‘I still can have just about any woman in Rome,’ Emilio told him.

‘Yeah. But why?’

‘Because I don’t want the same picture over the fireplace everyone else has. Leave it at that.’

‘I don’t get it.’

Emilio had thrown a big arm around the kid. Mickey inherited the physique of his mother. He was lean, muscular, good-looking too. It was a shame he always chose clothes too young for him, though. And that he’d dyed his shoulder-length hair an overpowering, unnatural blonde colour. ‘You don’t have to. Just don’t snap at each other all the time. Not when I’m around anyway.’

‘Sorry,’ he’d replied, instantly deferential.

The old man never said as much but sometimes he didn’t get it either. Adele was unlike any woman he’d ever slept with: cool, adventurous, always willing, whatever he wanted. Young as she was, she actually taught him a few new tricks. Maybe that clinched it. He knew for sure it wasn’t her personality, which he didn’t really understand beyond her basic need for money and security. She was an expensive pet, if he were honest with himself, a living ornament to add some beauty to his life.

‘So,’ Neri declared, looking in turn at the two of them. ‘What does my family plan to do today?’

‘Are we going out?’ she asked. ‘We could have lunch somewhere.’

‘Why bother?’ Mickey said, smirking. ‘I could send someone down the Campo. Buy you a couple of lettuce leaves. They’d last all week.’

‘Hey!’ the old man bellowed. ‘Cut it out! And quit sending servants out to buy stuff you can get yourself. I don’t pay them to get you cigarettes.’

Mickey went back to the sports car magazine he was reading and said nothing. Neri knew what the kid was thinking: so what do you pay them for? Neri never liked the idea of servants in the house. Adele said their position demanded it. He was the boss. He was supposed to own people. It grated somehow. Emilio Neri grew up in a traditional Roman working-class family, fighting his way out of the Testaccio slums. He still felt embarrassed by these minions downstairs. A couple were made men, there for security. He had no problem with that. But a house was for family, not strangers.

‘I got work to do,’ Emilio said. ‘People to see. I won’t be back until this afternoon.’

‘Then I’ll go shopping,’ she answered, with just a hint of hurt disappointment in her voice.

Mickey was shaking his blonde head in disbelief. Adele did a lot of shopping.

‘You!’

‘Yeah.’ Mickey closed the magazine.

‘Go see that louse Cozzi. Squeeze his grapes and ask for some accounts. The creep’s screwing us somehow. I just know it. We should be taking more in one week than he hands over in a month.’

‘What do you want me to do if I see something?’

‘If you see something?’ Neri walked over and ruffled Mickey’s wayward hair. ‘Don’t play the tough guy. Leave those decisions to me.’

‘But—’

‘You heard.’

Neri looked at the pair of them. Adele was acting as if the kid didn’t even exist. ‘I wish you two could work up the energy to be civilized to each other once in a while. It would make my life a whole lot easier.’ He watched. They didn’t even exchange glances.

‘Families,’ Neri moaned, then phoned downstairs, telling them to get the Mercedes ready. He keyed in the security code that unlocked the big metal door. It felt like a prison sometimes, hiding behind the bodyguards, riding around in a car that had been discreetly filled with bullet-proof panelling. But that was the way of the world these days.

‘Bye,’ Emilio Neri grunted, and was gone, without even looking back.

Mickey waited a while, pretending to read the magazine. Finally he put it down and looked across at her. She’d finished the orange juice. She was lying back on the sofa in her perfect silk pyjamas, eyes closed, glossy red hair splayed out on the white leather. Pretending she was asleep. She wasn’t really. They both knew that.

‘Maybe he’s right,’ he said.

She opened her eyes and turned her head lazily, just enough to meet his gaze. She had very bright eyes, vivid green, never still. Not smart eyes, he thought. Just sufficiently expressionless to hide the odd lie.

‘About what?’

‘About us getting along a little better.’

She became alert, alarmed perhaps. She looked at the door. There was a hard cast in her face: fear.

Mickey got up, stretched his arms and yawned. He was wearing a thin tee-shirt and tight designer jeans. She watched him, worried. They heard the sound of the big main door to the street slamming shut three floors below, and then, directly after, the growl of the departing Mercedes.

Adele Neri got up from the sofa, went to the door and threw the bolt, walked across to her stepson, put a hand on his fly and ran the zip down, clutching at what was inside.

‘You need to shop for new pyjamas,’ Mickey said.

‘What?’

He took hold of the neckline of her top and tugged hard with both hands, tearing at the silk. The fabric ripped wide open. Her meagre white breasts came under his fingers. He bent down, sucking at them briefly, then jerked down the pants, helping her shrug out of the things, running his palms everywhere, letting his tongue work briefly into her small, tight navel, then slide lower into the thatch of brown hair.

Mickey got up, cupped his hands around her thin, tight buttocks, gripped her thighs, lifting her into the air, pushing backwards until her shoulders were up against the door. The green eyes looked into his. Maybe there was an expression there. Need. Maybe not.

‘Never much wanted to bang a skinny chick until you came along,’ he mumbled. ‘Now I don’t want to bang nothing else.’

She was doing things with her hands, things that were sneaky and gentle and rough and unsubtle at the same time. He was hardening in her fingers. His jeans were round his ankles now. She hitched up her legs and straddled his waist, holding on tight, guiding him.

‘If he ever finds out, Mickey—’

‘We’re dead,’ he said, and felt his body meeting hers in all the right places.

Mickey Neri pushed himself forward, stabbing into her. It was the best feeling he’d ever known. She was squealing. She was going crazy, chewing on his neck, whispering filthy words into his ear, pulling his long hair. He pushed harder. He was in deep, as deep as it got.

‘Worth it,’ he panted, knowing already he’d have to work hard to prolong the pleasure. Maybe she knew some tricks there too. ‘Worth every second.’

‘OK,’ Teresa Lupo said briskly. ‘I spent many nights sweating over this but I’ll try to compress it as much as I can. Look—’

They did as she wanted, and got up to stand over the cadaver. She seemed quite young, Costa thought, halfway between girl and woman. Perhaps seventeen, if that. Her face was disconcerting, still alive somehow and undoubtedly beautiful. Her features seemed Saxon or maybe Scandinavian. They had the precise, symmetrical perfection he associated with fair-haired northerners. Someone had washed part of her matted hair. It was now a kind of muddy blonde, tinted by the redness of the peat. The smell was pungent close up too.

‘You will recall,’ Teresa said, pointing at the cavity around the cadaver’s throat, ‘that our thoughtful American friend tried to remove her head believing it to be that of a statue. This wound was caused by the sharp end of his shovel. I’m amazed you people let the bastard go without doing a single thing to him, by the way, but that’s your decision not mine.’

‘Here, here,’ Peroni agreed.

‘We went through this, Gianni,’ Costa said. ‘What were we supposed to charge them with?’

‘Drunk driving?’ Peroni suggested.

‘Couldn’t hold them in the country until trial.’

The older man scowled. ‘How about disrespect? Yeah, I know. It’s not a crime. Maybe it ought to be.’

Teresa smiled at Peroni and said, ‘I agree.’ Then she took a pointer and indicated an area on the girl’s neck, just above the deep gash made by Bobby Dexter’s spade. ‘You can still see what happened originally though. That shovel wasn’t the first time someone struck a blow here. The girl’s throat was cut. From behind too. From the wound you can see whoever did it worked from side to side. It doesn’t work like that if they come in from the front. Then you just get a slash from the centre out. Here—’

There were more pictures on the desk. Careful blowups of the neck. ‘There’s the slice the bozo made. There’s hardly any earth on the tissue. But here—’

They looked closely at the photos. Close up the second, older wound, clearly tinted by the brown, acid water over the years, was unmistakable.

‘That didn’t happen two weeks ago. That happened not long before she got put into the bog. That killed her.’

Falcone nodded at the pictures. ‘Good work,’ he said. ‘That was all I wanted to know.’

‘There’s more,’ she added, trying not to look too eager.

Falcone laughed. She found it disconcerting that she amused him. ‘Don’t tell me, doctor. You’ve solved the case. You have a motive. You know when. You know who did it.’

‘That last part’s beyond even me. The rest … be patient.’

The inspector smiled, amused, and waved her to go on.

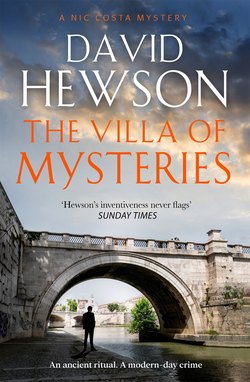

There was a book on the desk. She picked it up, and held it up for them to see. It was entitled Dionysus and the Villa of Mysteries. The cover photograph was of an ancient painting: a woman in a dishevelled dress, holding her hand over her face in terror of some halfseen night creature with staring, demonic eyes which leered at her from the edges of the image. The shapes had been damaged over the years. The creature was largely unrecognizable. But they could see what was depicted here. It was some kind of ceremony, one in which the woman was, perhaps, assaulted. Or even sacrificed.

‘This was written by a professor at the university here,’ she said. ‘I got put onto it by an academic at Yale who’d done some work on a bog body found in Germany, close to a Roman town.’

‘This is relevant?’ Falcone asked.

‘I think so. Most of these deaths weren’t accidental. There was some kind of ritual going on. The guy who wrote this is trying to work out what that might be.’

‘Something to do with Dionysus?’ Costa asked. ‘I don’t get it. That’s Pompeii. We went there on a field trip when I was at school.’

‘So did we,’ Peroni added. ‘First time I ever got drunk.’

‘Jesus,’ she said. ‘What a pair you two make. Yes, Nic. The Villa of Mysteries is at Pompeii and, according to this guy, who is, I am reliably informed, the world’s living expert on the Dionysian mysteries, it is important. But it wasn’t the only one. Pompeii was the provinces. Suburbia if you like. It was small time compared to what went on elsewhere. In Rome in particular. Ask yourself. Who’s got the biggest churches? Us or them?’

Falcone sighed. ‘Point taken. And this book says what exactly?’

She waved the cover at them. Costa glanced at the terrified woman there. It seemed such a modern image. ‘Dionysus was a cult imported from Greece. You probably know him better as Bacchus.’

‘Booze?’ Peroni wondered. ‘You mean this is the result of a drunken orgy or something?’

She grimaced. ‘You watch too many bad movies. Dionysus was about much more than drink. This was a secret cult, banned as a pagan one even before Christianity because of what went on. Not easy to stamp out either. There were Dionysian rituals going on in Sicily and Greece until a few centuries ago. Maybe they’re still happening and we just don’t know about them.’

Falcone stared pointedly at his watch. ‘My jurisdiction ends at Rome.’

‘OK, OK,’ she conceded. ‘Rome.’

Teresa Lupo opened the book at a page marked with a yellow sticky note. ‘Here are some pictures, from a place in Ostia. Still suburbia, but around the time this girl was put in the bog this was Rome’s harbour town and a sight bigger than Pompeii. Lots of rich people. Lots of substantial villas on the edge of town, including this one …’

She pointed at an outline on the map then turned the page. There was a series of photographs of an old, churchlike building, then some interior shots of wall paintings. One of the scenes was the image from the front of the book. The rest was a frieze of dancing figures, human and mythical, dancing, coupling.

‘Pompeii has a much fuller set of wall paintings. What they seem to show – at least the book claims – is the initiation ceremony for the cult. Not that anyone much understands them these days. The point is that they were all over the place. At Ostia. In Rome too. Probably with the big one hidden somewhere not far from the centre. The holy of holies.’

‘What he calls the Palace of Mysteries?’ Costa asked.

‘Exactly,’ she said, nodding. ‘Which is probably where this poor kid died. I took a good look at the dirt beneath her fingernails. It’s not estuarial. It didn’t come from Ostia. It could be from anywhere in central Rome.’

Peroni looked lost. ‘You mean these were temples or something? And they kept them hidden?’

‘Not quite. More like fun palaces in the dark they could use when the time came.’

Peroni put his finger on the page and traced over the paintings. ‘Use to kill people?’

Teresa shrugged. ‘I dunno. You read this book and sometimes you think the guy is sure of what he’s saying, sometimes he’s making it up. What he thinks is that there could be bad consequences if the initiation went wrong. There was some kind of mysterious act which had to be performed with a representative of the god. Sexual, probably. Everyone got doped up to the nines so I imagine most of the time they didn’t have a problem getting their way with these kids. But if the initiate backed off …’ She didn’t need to say the rest.

‘She a virgin?’ Peroni asked.

‘I told you. I put off performing a full autopsy until I could get some idea of the date. Now we know I can pass it on to the archaeology people at the university. They can try to find out. From what I’ve seen it’s going to be impossible to tell. Sorry. Do you need to know?’

‘Maybe not,’ he admitted. ‘Look. Like I said, I’m no detective. But it seems to me there’s not a lot of meat here. Could be it’s all coincidence. Also – and I hate to point this out – that dating stuff just dates the dirt beneath her fingernails. Don’t date her.’

‘I know, I know,’ she said firmly. ‘Stay with it. I’m building a case here. You see what’s in her hand?’

The girl was holding some kind of wand or standard about a metre long, clutched to her side, the head disappearing under her arm. At the base was a protuberance of some kind, round and knobbly.

‘This is exactly what the book describes, and that isn’t conjecture. It’s based on historical sources. I took samples. It’s made from several bound stems of fennel. At the top there’s a pine cone, wound into the staff. The thing’s called a “thyrsus”. It’s standard issue for Dionysian rituals. Look—’

She turned the pages of the book. There was a picture of a female figure, half dressed, holding the same kind of object, waving it in the face of a satyr, half man, half goat, leering at her.

‘It’s used for protection. And purification.’

‘Have you dated that?’ Falcone asked.

‘Radiocarbon costs,’ she snapped. ‘You want me to spend time and money on this instead of something fresh off the street?’

Falcone nodded at the book. ‘Just asking. You’ve worked very hard, doctor. Congratulations.’

He still didn’t seem that interested.

‘There’s one thing left,’ she said quickly, as if she thought they might leave the room any moment.

‘That is?’

‘They found it with a metal detector, remember. How? There’s nothing metallic on her body. No necklace. No rings. No armlet.’

She wanted them to come up with an answer. It didn’t happen. Teresa Lupo went back to the desk and returned with an X-ray of the head. She placed it on the cadaver’s stomach. ‘See?’

It was a straight-on image of the girl’s skull. There was a bright object there, quite small, in the lower third.

‘A coin beneath the tongue,’ she said. ‘To pay Charon, the ferryman who took the dead across the Styx to the Underworld. Without it you never got there. I didn’t need any book to tell me that. I loved mythology when I was a kid.’

To Nic Costa’s surprise, Falcone was abruptly animated by this discovery.

‘You’ve got it? The coin?’

‘Not yet,’ she said. ‘I was waiting for you.’

‘Please—’

‘Hey! I have other work you know.’

They did know that. They also knew how much she liked to be right, and seen to be proved so.

She looked at the face, the half open mouth, the perfect stained teeth. Then she examined the X-ray again, wondering where to start.

Teresa Lupo picked up a scalpel and, with one careful, clean movement, made an incision in the girl’s left cheek, level with her lower lip. She put the scalpel down then picked up a small pair of shiny steel forceps.

‘They dated coins in those days. If this one’s anywhere in the range I outlined I expect you gentlemen to buy me dinner, one by one, in a restaurant of my choosing.’

‘It’s a deal,’ Falcone replied immediately.

‘Ooh!’ Teresa squealed with a fake girlish glee as she exercised the forceps, making sure they would do the job. ‘Dinner with cops! Aren’t I the lucky one? What will we talk about? Football? Sex? Experimental philosophy?’

The forceps entered the slice in the cheek. She turned the instrument deftly, probing, feeling, pushing. Then the arms clamped on something.

‘Pass me one of those silver trays,’ she said to Costa. ‘This is going to cost you guys plenty.’

Slowly, she retrieved the forceps from the girl’s mouth and placed an item in the dish. Then she poured some fluid into the pan and cleaned the thing gently with a tiny brush.

The object was a small coin which came up quite shiny. It was silver on the edges with a bronze centre, though both colours looked as if they were slowly transforming to copper through the stain of the peat. It was also familiar.

Teresa Lupo pulled over a large magnifying glass on a swan neck stand. The four of them crowded around the lens, peering at the thing. She turned it over. Twice. Just to make sure.

Peroni stood next to her, shaking his head. ‘My boy used to collect coins until someone told him it was uncool,’ he said. ‘I helped him sort out his collection. Bought him one of those, mint condition. Dated the first year they issued it, 1982. Five hundred lire. You know something? It was the world’s first bi-metallic coin. No one had made one that was silver on the outside and bronze in the centre before. One other thing. If you look at the obverse, above the picture of the Quirinale, you’ll see the value written in Braille. That was unique too.’

No one was really listening. Peroni bristled. ‘Hey. Stupid old cop is sharing information here. Are you taking notes or am I speaking for my own benefit?’

‘Shit,’ Teresa Lupo whispered, glaring at the coin. ‘Shit.’

‘You mean the body’s been in the peat for not much more than twenty years?’ Costa asked.

‘Not even that,’ Falcone said.

They all turned to look at him. The inspector had returned to his briefcase and now had a folder in his hands. He opened it and took out a photograph. It was a portrait of a girl in her teens. She had long fair hair down to her shoulders. She was smiling for the camera.

He placed the photograph on the cadaver’s chest, over the X-ray of the skull. The features were identical.

‘You knew?’ She couldn’t believe this, couldn’t contain her amazement and anger. Peroni was chuckling, his shoulders rising and falling as if they were plugged into the mains.

Falcone was bent over, examining something on the girl’s left shoulder. A mark. A tattoo maybe.

‘Just guessing to begin with. You have to remember, doctor. I didn’t get back from holiday till yesterday. I hardly had the time to dig this …’ he waved the case folder, ‘… out of the vaults.’

‘You knew?’ she repeated.

He bent down and looked at the mark on the girl’s skin. Costa did the same. It was a tattoo, circular, about the size of the coin: a howling, insane face with huge lips and long dreadlocks.

‘It’s supposed to be a mask from an imperial Roman comedy,’ Falcone said. ‘Dionysus was the god of theatre too. This was used by the Dionysian cults. You deserve that dinner, doctor. I’ll honour the bet. You were almost there. Just a couple of millennia out.’

Teresa Lupo pointed a stubby index finger at the inspector’s chest. ‘You knew? Eat your fucking dinner on your own.’

‘So be it,’ he answered. They watched him. Falcone couldn’t take his eyes off the tattoo. There was something going on inside the inspector’s head, something he didn’t seem much inclined to share.

‘You’ll cancel the press conference,’ he said.

‘You bet,’ she grumbled mutely. ‘But what should I say?’

‘Make an excuse. Say you’ve got a headache. Tell them we don’t have the people, what with this flu thing and all. It’s the truth anyway.’ He picked up the photograph from the dead girl’s chest and put it back in the envelope. Costa couldn’t help but notice Falcone hadn’t even let them see a name.

‘Sir?’ Costa asked, puzzled.

‘Mr Costa?’ Falcone’s sparkling eyes gave nothing away. ‘It’s so nice to have you back with us.’

‘What do you want us to do?’

‘Catch a few crooks I imagine. Go help out down the Campo. There’s a lot of pickpockets there at the moment.’

‘I meant about this.’

Falcone took a final look at the corpse. ‘About this … nothing. The poor kid’s been lying in the mud for sixteen years. A day or two won’t make much difference.’

He rounded on all three of them. ‘And let me make one thing clear. I don’t want you breathing a word of what we have here to anyone. Not in this building. Not outside. I’ll call you when I need you.’

They watched him walk purposefully out of the room. Teresa Lupo stared at the body, her big, pale face a picture of misery and disappointment.

‘I had it all worked out,’ she moaned. ‘I knew exactly what happened. I talked to these academics and people. Jesus …’

‘You heard him,’ Costa said. ‘You did well. He meant it.’

Teresa was running her fingers over the dead girl’s mahogany skin. She didn’t need Nic Costa’s sympathy. She was over her disappointment already. It had been displaced by something new, something potentially more interesting.

The cadaver on her dissecting table was no longer a historical artefact. It was a murder victim. It required her attention.

Costa looked at the silver scalpel in her hand then looked at Peroni.

‘The Campo it is,’ he said and the older man nodded back in agreement.

‘I guess there really is no rush,’ Peroni said in the car. ‘I just wish Leo would talk to us some more. I hate getting left in the dark.’

Costa shrugged. He knew Falcone well enough not to let this bug him. ‘In his own time. It’s always like that.’

‘I know. He’d be a disaster in vice. You got to take people with you all the way there.’ Peroni must have watched Falcone work his way up the ranks. Their relationship was hard to fathom, half amiable, half suspicious. That was hardly unusual. Falcone was a smart, sound cop, one who trod a fine line sometimes when he felt a case merited it. He’d won plenty of respect for his talents. He was straight, unbending on occasion. But he didn’t give a damn about popularity. Sometimes, Costa thought, Falcone actually liked the antipathy and near-hatred he generated. It made tough decisions easier to take.

Peroni lit a cigarette and blew the smoke out of the window. ‘You asked Barbara Martelli out yet?’

Where did that one come from, Costa wondered. ‘Haven’t found the right occasion.’

Peroni stared at him with a face that said: are you kidding me?

‘I’m not ready. OK?’

‘At least that’s honest. How long’s it been since you went with a woman? You don’t mind my asking. We have these conversations in vice all the time.’

‘I guess in vice you measure it in hours,’ Costa answered without thinking and immediately wished he could bite back his words. Peroni’s face fell. He looked hurt.

‘I’m sorry, Gianni. I didn’t mean that. It just slipped out.’

‘At least we’re on first-name terms now. I guess that means we can say what we want to each other.’

‘I didn’t—’

‘It’s OK,’ Peroni interrupted. ‘Don’t apologize. You have every right to tell me when I’m acting like a jerk.’

Peroni was more complicated than he liked to appear. That much Costa had come to understand. Some part of him wanted to talk about what had happened too, even if he felt he ought to make a play of avoiding the subject.

‘Why did you do it, Gianni? I mean you got a family. Then you go with a hooker.’

‘Oh come on! It happens every day. You think it’s just single men get horny from time to time?’

‘No. I just wouldn’t have thought it of you.’

Peroni let out a deep sigh. ‘Remember what I told you once? Everyone’s got that dark spot.’

‘Not everyone lets it out.’

The big, ugly head shook slowly. ‘Wrong. One way or another they do. Whether they know it or not. Why did I do it? Won’t a simple answer do? The girl was damn beautiful. Slim and young and blonde. And young. Or did I mention that? Maybe she made me feel alive again. When you’ve been married twenty years you forget what that’s like. Yeah, before you say it, so does your wife. Blame me twice over.’

Costa said nothing, worried he might cross the line and destroy the delicate bonds the two of them had managed to build over the last few weeks.

Peroni’s damaged face wrinkled some more in puzzlement at his silence. ‘Oh. I get it. You’re thinking, “Who does this hideous bastard think he is? Casanova?”’

‘You don’t look like the great Latin Lover. That’s all. If you don’t mind me saying so.’

‘Really?’

‘Really.’ Costa knew what was going on here. He wondered if he dared ask.

‘Are you calling me ugly? That happens from time to time, Nic. I have to tell you I don’t like it.’

‘No …’ Costa stuttered. He took a good look at that battered face. ‘I was just wondering.’

‘What?’

‘What the hell happened?’

Gianni Peroni burst out laughing. ‘You kill me. You really do. In all the time I’ve worked here you are the first person who’s come out and asked that question direct. Can you believe that?’

‘Yes,’ Costa said hesitantly. ‘I mean, it’s a personal question. And most people wouldn’t like the idea that you could take it the wrong way.’

He waved a huge friendly hand in Costa’s face. ‘What the hell do you mean a personal question? You guys have to look at this ugly mug every day you come to work. I got to live with it. This …’ he pointed a fat index finger at his face, ‘… is just a fact of life.’

Costa felt he’d made progress of a kind anyway. ‘So …?’

Peroni chuckled again and shook his head. ‘Unbelievable. Just between the two of us, OK? This goes no further? No one knows this. Most of the guys out there think I look like this through getting into a fight with a hood or something. They wonder what the other guy looks like too. I’m happy with things that way.’

Costa nodded his agreement.

‘A cop did this to me,’ Peroni said. ‘I was twelve years old. He was the village cop. I was the village bastard. I mean that literally. My mamma worked for the couple who owned the lone bar in town and got knocked up after the fair some time. She always was a little naïve. So I spend twelve years being the village bastard, getting the village bastard treatment all those years. Spat on. Beaten up. Laughed at in school. Then one day the moronic kid in the same class who was my principal tormentor went just a touch too far. Said something about my mamma. And I kicked the living shit out of him. First time I ever did that. You want the truth? It’s the only time I ever did that. Don’t need to now. I just look at people and go, Boo …’

Costa thought about it. ‘I can believe that.’

‘Good. The stupid thing was, I forgot the moron I was beating up was the village cop’s kid. So Daddy comes along, and Daddy’s been drinking. One thing leads to another. He gets done with the strap and he’s still not happy. So he goes and gets these metal things he carries, just for protection you understand, and he puts them on his fists.’

Peroni watched the cars go by out of the window. ‘I woke up in hospital two days later, face like a pumpkin, Mamma by my side. I couldn’t see a thing. The first thing she says is, don’t even think of telling anyone. He’s the village cop. Second thing she says is, don’t look in the mirror for a while.’

Costa sighed. ‘You could have told someone.’

Peroni gave him a frank look. ‘You’re a city kid, aren’t you?’

‘I guess so.’

‘It shows. Anyway, a couple of weeks later I come out of hospital and I notice things are different. People look at me and suddenly their eyes are on their shoes. A couple cross the road when they see me walking down the street. You know the worst thing of all? I was helping my uncle Fredo sell those pigs at weekends then. I went back to it. What else could you do? After a while he comes to me, tears in his eyes, and fires me. No one buys food from someone with a face like this. That was the worst thing of all at the time. I didn’t want to do anything else when I grew up except raise those pigs and sell them every weekend. Those guys … they all look so happy. But—’

He folded his arms, leaned back in the passenger seat, and glanced at Costa to make sure this point went in. ‘That was not to be. I became a cop instead. What else do you do? Partly to spite that old bastard who beat me up. But mainly, if you want to know, to even things up a little. I’ve never laid a finger on anyone in this job. Never would, not unless there was a very good reason and in more than twenty years I never found one. It’s a question of balance.’

Costa didn’t know how to respond. ‘I’m sorry, Gianni.’

‘Why? I got over it years ago. You, on the other hand, have spent the last six months going loopy inside a bottle of booze. I’m sorry for you, kid.’

Maybe he deserved that. ‘Fine. We’re even now.’

Peroni was peering at him with those sharp, all-seeing eyes. ‘I will say this once, Nic. I am starting to like you. A part of me says that I will miss this time we’re spending together. Not that I wish to prolong it you understand. But let me offer some sincere advice. Stop trying to fool yourself you’re something special. You’re not. There are millions of people out there trying to cope with fucked-up lives. We’re just two in the crowd. And after that little lecture …’ he said, stretching up in his seat as Costa parked the car in a tiny space off the road by the ghetto, ‘… let me make a request.’

Peroni looked into his face, hopefully. ‘Cover for me. I got something important to do. I’ll meet you back here at two.’

Costa didn’t know what to say. Bunking off for a couple of hours wasn’t unknown. He just didn’t think Peroni was the kind of cop to do it.

‘Anything I should know about?’ he asked.

‘Just personal. It’s my daughter’s birthday tomorrow. I wanted to send her something that might make her think her father is not quite the jerk she’s come to believe. You can cope with the Campo on your own. Just don’t pick on any big bastards, OK?’

Leo Falcone was reading the file on his desk, trying to focus on the case. He didn’t want to rush anything. Going public too quickly only alerted those he would wish to interview, though given how leaky the Questura had proved of late they probably knew by now anyway. The pause would also give him time to turn his mind back towards work after a solitary two weeks spent at a luxury beachside hotel in Sri Lanka. He had met no one of interest, and had scarcely sought the company of others. It was an unsatisfactory, tedious respite from routine that left him mildly disturbed. He was glad to be back at his desk and with a challenging case to tackle.

Even so, a rare note of self-doubt lurked at the back of his mind. Falcone had, to his surprise, been aware of his own loneliness during the long, drab holiday. It was now five years since his divorce. There had been women in that time, attractive, interesting women. Yet none had stimulated him sufficiently to take the relationship beyond the routine round of meals, the cinema, and the physical necessity of the bedroom. He’d come to realize the previous night – when, completely out of character, he’d consumed an entire bottle of a wonderful, deeply perfumed and expensive Brunello – that there had been only two real lovers in his life: his English wife Mary, who was now back in London, pursuing a legal career; and the woman who was the reason Mary left, Rachele D’Amato.

Here, in the light of day, obscured only slightly by the remains of a hangover, lay a curious coincidence. In Sri Lanka he had thought consciously about these two women for the first time in several years. When he returned to Italy, it was to find them ready to re-enter his life. Mary had written to invite him to her marriage, to another rich English lawyer, at a country house in Kent. He would find an excuse and decline. She would, he thought, expect this. The invitation came out of politeness, nothing more. His infidelity had wounded her deeply, and her abrupt departure, without the slightest attempt at reconciliation, hurt him more than he realized at the time. Or perhaps the pain came from Rachele D’Amato, who had abandoned him with the same degree of certainty Mary had shown, and rather less grace, the moment he became free.

He’d never forgiven himself for allowing these events to happen. He never forgave them either. And now Mary was getting married, while Rachele was a successful lawyer turned investigator, steadily working her way up the ranks of the DIA, an organization which, thanks to the case Teresa Lupo had placed before him, Falcone knew he must soon approach.

His feelings about the DIA went beyond the recent sting that had wrecked Gianni Peroni’s career, an exercise that was more about public relations than the defeat of organized crime. They stretched back years. There was scarcely a cop in the Questura who didn’t hear those three initials and feel a small sense of dread. He realized, the moment the dead girl’s identity became plain, that there could be no avoiding them. Strictly speaking he should have acted already, as soon as he realized the kind of people he would have to interview.

Falcone stared at the pages and pages of reports and tried to remember what the case was like when it was fresh. Sixteen years before he’d just been a plain detective. The inspector in charge was Filippo Mosca, an old-fashioned Rome cop who walked both sides of the track and, like many a man of his generation, made little effort to hide his friendship with people who were best avoided.

Eleanor Jamieson was reported missing on 19 March, a full two days after her American stepfather last saw her. She had just turned sixteen and had been living in Vergil Wallis’s rented villa on the Aventine hill since arriving from New York the previous Christmas. The girl was English. Her mother had left Wallis a year before, after a marriage that lasted just six months. Falcone never could find out why. Nor would he. The woman killed herself in New York ten days after the disappearance of her daughter.

It was, Falcone recalled, a maddening case. Wallis was a curious man: educated, almost scholarly, yet black and originally from the ghetto. He was in his mid-forties then, vague about his business and his antecedents, a reluctant witness, unforthcoming about the girl’s movements, what friends she had made in the city, any motive she might have to run away. The man had no good reason to explain why it took two days to report her absence, simply pleading that meetings had called him out of Rome. He had even seemed reluctant to hand over the few photographs he possessed, which revealed a young, naïve-looking girl, very pretty, with shoulder-length blonde hair and a ready smile. And, on her shoulder, fully revealed in a picture taken a day before she vanished, the curious tattoo, for which Wallis had no explanation. It had fascinated Falcone from the moment he saw it. There was a craze for tattoos at the time. All the rock stars and the hotshots in the movie world were doing it. But they didn’t have anything like this etched into their skin. The ancient hieroglyph looked wrong on the girl, more like a branding mark than some badge of fashion.

It seemed out of character too, as much as any of them could judge. According to Wallis, Eleanor had bummed around Italy for a while then spent two weeks on an intensive Italian course at a language school near the Campo. She was an intelligent girl, with good exam grades. There was talk of her going to study at an art college in Florence later that year. She had few acquaintances beyond the school and, if Wallis was to be believed, no boyfriend, current or ex. Nothing they could turn up explained why she should suddenly disappear. She had, her stepfather said, simply set out for school on her scooter around nine on the morning of 17 March and never arrived.

It only took a couple of days for Mosca’s team to acquire the sickening sense of powerlessness that comes with abduction cases. No one had seen Eleanor on her way into the city. A re-creation of her supposed last movements on TV failed to elicit a single reliable response from the public. It was as if she had existed one moment and then been abruptly removed from the face of the earth.

All along Falcone wanted to scream foul. Because something stank to high heaven and pretty soon he had an inkling what it was. Mosca had taken him to one side on the third morning and told him, in confidence, what he’d heard the previous night from a friend in the Foreign Ministry. Vergil Wallis was not, as he claimed, a straight-forward businessman from LA who loved Rome so much he was thinking of buying a second home in the city. He was a high-up figure in the West Coast mob, a black fixer who’d risen through the ranks to live in Italy half the year for his own crooked reasons. Interpol had been following Wallis for years and steadfastly failing to bring him to justice on a wide range of counts, from racketeering to murder. Nor had the carabinieri, who had been assigned to Wallis’s case, fared much better.

This was shortly before the creation of the DIA. Then, as now, the civilian state police maintained an uneasy rivalry with the carabinieri, who were part of the military. The lines of responsibility were, at best, blurred and on occasion deliberately murky. Privately Falcone was in agreement with the growing number of critics calling for a single, unified state police force. It was a logical, inevitable solution. But this was judged a heresy by those in charge of both organizations, and one that could cost a man his job. He was careful never to make his views known. They were, in any case, irrelevant. Soon the DIA came along, adding another layer of complexity to the business of chasing the swelling tide of crime that seemed to grow stronger with every passing year.

And Vergil Wallis was still free. So much for progress.

Mosca quietly closed the case of Eleanor Jamieson, marking it unworthy of further investigation without new evidence. Wallis’s relationship with the Italian mobsters was far from easy. Some stories, garnered at great expense and with no small risk to those who supplied them, placed him in the role of criminal diplomat, a go-between trying to ensure the interests of his own particular buddies meshed with those of the Sicilians. It made sense to Falcone. The West Coast mob that Wallis represented was only loosely connected to the Italian organizations in the USA. There was plenty of room for misunderstandings. The bosses had learned long ago that pacts and partnerships, even with those they hated, put more dollars in their bank accounts than ruthless competition and turf wars. Money was what mattered these days. No one went to the barricades over honour any more. These were practical times in which cash was king.

Falcone had been present at three different interviews with Wallis and still couldn’t work out what to make of the man. The American was thoughtful and articulate, quite unlike any crook Falcone had ever met. He was well read. He knew more about ancient Roman history than some Italians. The word was that he’d been groomed for the role of diplomat for years, put through law college after rising through the black ranks in Watts. It wasn’t hard to see him smoothing out the rough edges of a relationship which must always have hovered on the brink of disaster.

There was, however, one fundamental problem. If the street gossip was right, he had been given as his prime contact Emilio Neri, a brutal thug who had worked his way from the public housing slums of Testaccio to the pinnacle of the Rome mob through the vicious and heartless disposal of anyone who stood in his way. Neri now sat on the boards of opera houses in Italy and America. He lived in an elegant house in the Via Giulia, behind an army of servants and bodyguards. It was a place Falcone knew only too well from his many futile visits there. The old crook had a carefully cultivated outward appearance of elegance, a mask of deceit worn for the public. It only fooled those who were too stupid or too scared to realize the truth. Almost from the moment Falcone had joined the force he had followed Neri’s career, and with good reason. The man habitually bribed any cop who would take his money, simply to put him on side. Falcone himself had turned down a thinly disguised offer of money from one of Neri’s hoods in the middle of an investigation into a protection racket involving some of the smaller shops off the Corso, an assignment Filippo Mosca had closed down just when it was making progress. Three cops who were known to be on Neri’s payroll had been jailed for corruption in the past decade. Not one named him as the source of the largesse found in their bank accounts. They preferred prison to the consequences of his fury.

What set Neri apart from his fellow hoods was the obsessive system of personal control he wielded over his own family. Most bosses of his stature had long since ceased to dirty their hands with the day-to-day business of running a crime organization. Neri never stepped back from the front line. It was in his blood from the old days in Testaccio. He liked it too much. Word had it he still enforced his rule in person from time to time, with the same harsh violence he’d employed as a young hood. Maybe he got one of his junior thugs to hold the poor bastard down while Neri went about his work. Falcone had looked into the old crook’s dead, grey eyes often enough to understand the pleasure it would give him.

He read the last page of the report and, knowing the volatile and untrustworthy Neri as he did, understood every word. It said that Wallis and Neri had, initially, proved the best of friends. Their families had dined with each other. Six weeks before Eleanor Jamieson died, she and Wallis had spent some time on holiday with the Neri family on one of their vast estates in Sicily. Some undisclosed form of business had been done. The Americans were happy. So were the mob.

Then, around the time of the girl’s disappearance, a coldness had entered the relationship. There had been reports that, while in Sicily, Wallis had gone over Neri’s head to talk to some of the senior bosses there, something Neri would soon learn about. There was rumour of a drug deal that had gone wrong, leaving the Americans out of pocket and angry. Neri never could resist taking people to the limit. He skimmed every last dollar that went through his hands, even after his ‘legitimate’ cut.

Some huge row took place between the two men. One informer even said they came to blows. After that, they were both in trouble with their bosses. Neri was told bluntly he was losing the job of linkman with the Americans. Wallis got a dressing-down too, though he continued to live in Rome for half of the year, with precious little to do except save face. It was an uneasy truce. One of Wallis’s lieutenants was murdered two months later, his throat cut in a car close to a Testaccio brothel. Not long after, a cop on Neri’s payroll was found dead in what had been made to look like suicide. Falcone wondered, was there a link here? Would the semi-mummified body of a sixteen-year-old girl raise these old ghosts from their graves? And if it did, how different would the world be now, with the DIA peering inquisitively over his shoulder every step of the way?

Leo Falcone looked at his watch. It was just after twelve. He thought of all the careful protocols which surrounded cases involving known mobsters. Then he took out his diary and placed the call.

‘Yes?’

Rachele D’Amato’s cool, distanced voice still had the power to move him. Falcone wondered briefly whether he was phoning her for the sake of the job or for more personal reasons. Both, he thought. Both were legitimate too.

‘I wondered whether you’d be there. Everyone else I call right now seems to be at home, sick in bed.’

She paused. ‘I don’t get to bed as much as I used to, Leo. Sick or not.’

There was a deliberate, slow certainty to her voice. Falcone understood what she was saying, or thought he did. No one else had filled her life after the affair ended. He knew that already. He’d checked from time to time.

‘I was wondering if you had time for lunch,’ he said. ‘It’s been too long.’

‘Lunch!’ She sounded pleased. ‘What a surprise. When?’

‘Today. The wine bar we used to go to. I was there the other evening. They have a new white from Tuscany. You should try it.’

‘I don’t take wine at lunchtimes. That’s for cops. Besides, I have an appointment. I have to run. We’ve got people sick everywhere too.’

‘Tonight then. After work.’

‘Work stops for you in the evenings these days, Leo?’ she sighed. ‘What happened?’

‘Nothing,’ he said. ‘I just thought …’

He felt tongue-tied, embarrassed. She’d always said it was the work that drove them apart after Mary left. It wasn’t. It was him. His possessiveness. His passion for her, which was never quite returned.

‘Don’t apologize,’ she said wryly. ‘It doesn’t stop for me either. Not any more.’

‘I’m sorry.’

‘There’s no need,’ she said, and there was a new note in her voice. A serious, professional one. ‘You have a body. Is it Wallis’s girl?’

‘Yes,’ he sighed, inwardly livid, wondering immediately who had talked.

‘Don’t sound so cross, Leo. I have a job to do too.’

The corpse had been lying in the morgue for two weeks. Anyone could have seen the tattoo and put two and two together. It would be impossible to find out who had blabbed.

‘Of course. You’re very good these days, Rachele.’

‘Thank you.’

He wondered why fate had made him fall in love with two lawyers. Why not women who were a little less curious? A little more forgiving?

‘Then we’ll meet,’ she announced. ‘I’ll call you. I have to go now.’

She didn’t even ask if it was convenient for him. Rachele never changed.

‘Leo?’

He knew what she’d say. ‘Yes.’

‘This is professional. Nothing more. You do understand that?’

Leo Falcone understood, though it didn’t stop him hoping.

Costa crossed the busy road and headed for the Campo dei Fiori, reminding himself he used to live here and there were memories, important ones, pieces of his personality stamped on the place. He missed the Campo from time to time. He was an innocent when he lived here, young and unbruised by the world. There’d been fleeting relationships, brief flings which Gianni Peroni probably wouldn’t count as love affairs at all. There was the place too. The cobbled piazza was grubby at the best of times. The market attracted too many tourists. The prices were higher than elsewhere. Nevertheless, it was a genuine part of Rome, a living, human community that had never been dislodged from its natural home. As always, he got a small rush of pleasure when he walked along the Via dei Giubbonari and came out onto the square. The stalls were still doing good business, selling spring greens, chicory, calabrese and cavolo nero alongside vibrant oranges from Sicily, stored over the cold months and now fit for little more than juice. The mushroom stand was piled high with all kinds of funghi, fresh chiodini, dried porcini. The handful of fishmongers tucked into one corner had scallops and giant prawns, turbot and sacks of fresh mussels. He worked his way through, picking up an etto of wild rocket and the same of agretti for later. Then he added a chunk of parmesan from the lone alimentari van.

‘We got good prosciutto, Mr Policeman,’ the woman said, recognizing him. ‘Here …’

She held out a pink strand, waving it in front of his face. If he ate meat, Nic Costa thought he’d be hard pressed to find much better in Rome. ‘I’ll pass.’

‘Vegetarianism is an unnatural fad,’ the woman declared. ‘You come back here one day when you’ve got time and we’ll go through this in some detail. You worry me.’

‘Please,’ Costa said. ‘I have enough people worrying about me just now.’

‘Means there’s something wrong.’

He took the prosciutto anyway. When she was out of sight he gave it to the scruffy young boy belonging to the Kosovan who was always begging in the square, playing an ancient violin badly. Then he handed the father a ten-euro note. It was a ritual he’d forgotten somewhere along the line too: twice a day, every day, as his late father had always told him. Being back in the Campo reminded him why it was necessary. He’d been spending too much time on his own, closeted inside the farmhouse on the outskirts of the city, thinking. Sometimes you had to get out and let life happen to you.

He’d just pushed his way through the crowd at Il Forno and was taking a bite of pizzetta bianca, salty and straight from the oven, when he saw what was happening. Leo Falcone was right. The Campo attracted tourists, and with the tourists came trouble. Pickpockets. Conmen. Worse sometimes. The police always had people on duty there, in uniform and out. The carabinieri liked the place too, parking their bright shiny Alfas in the most awkward of places and then lounging on the bonnets, eyeing the crowds through expensive sunglasses, trying to look cool in their dark, well-pressed uniforms.

Costa made a point of avoiding the carabinieri as much as possible. There was enough rivalry inside the Questura itself without extending it to these soldiers masquerading as cops. The demarcation lines were dimly drawn between this branch of the army and the civilian police. They could arrest the same people he did, and in the same places. Most of the time it was simply a matter of who got there first. There was an old joke: the good-looking ones joined the carabinieri for the uniform and the women, the smart and the ugly ones went into the state police because that was all they could get. It wasn’t all exaggeration either.

A couple of carabinieri were in the Campo now, standing stiffly upright by their vehicle as a slender blonde woman harangued them in mangled Italian, wagging her finger in their faces, holding a large, portrait-size photograph in her left hand.

‘Don’t get involved,’ Costa said to himself, and wandered over towards them in any case. The woman was livid. She knew a few good Italian swear words too. Costa took a bite of his bread and eavesdropped on what was going on.

Then he looked at the photo in the woman’s hand and something cold ran down his back, made him shiver so hard the pizzetta dropped straight from his fingers.

This was crazy. He knew it. The face in the photo reminded him of the picture Leo Falcone had thrown onto the strange corpse on Teresa Lupo’s dissecting table that morning. He thought of what he had seen there: an old image of a blonde-haired girl looking distinctly like the face he saw now, still at the beginning of her adult life, thinking there was nothing in the future but love and joy.

And it ain’t necessarily so, an old, old song sang at the back of his head.

The carabinieri were the pick of the crop. Prize assholes, more interested in keeping their Ray-Bans clean than working out what seemed to have happened in front of their very noses. He thought he recognized one. But maybe not. They all looked the same. These two sounded the same as well, with their middle-class nasal voices. They were sneering at the woman in front of them, exuding boredom.

‘Are you listening to me?’ she yelled.

‘Do we have a choice?’ one of them, the older one, Costa guessed, replied. He couldn’t have been more than thirty.

‘This,’ she said, pointing at the photograph, ‘is my daughter. She just got abducted. You idiots watched it and yawned.’

The younger uniform shot Costa a warning glance that said: don’t even think about getting involved. Nic Costa didn’t move.

The talkative one leaned back on the Alfa, shuffled his serge-clad backside further up the shiny bonnet, took out a packet of gum and threw a stick past his perfect teeth.

She stood in front of them, hands on her hips, full of fury. Costa glanced at the photo she was holding. They could have been sisters, but ten or fifteen years apart. The woman was a touch heavier. Her hair was a shade darker, more fair than her daughter’s bright, almost artificial, blonde, practical cut.

He walked over, watched her trying to get her breath back, then, struggling to remember his English, asked, ‘Can I help?’

‘No,’ the senior uniform said immediately. ‘You can just walk away and mind your own business.’

She looked up at Costa, relieved to be talking English at last. ‘You can get me a real policeman. That would be helping.’

He pulled out the badge. ‘I am a real policeman. Nic Costa.’

‘Oh fuck,’ the uniform with the working mouth muttered behind him.

He got up off the car and stood upright in front of Costa. He was a lot taller. ‘Her teenage daughter ran off with a boyfriend on a motorbike here. She thinks that counts as abduction. We think that sounds like some young kid looking for fun.’ The Ray-Bans cast the woman a dead, black look. ‘We think that’s understandable. If you people playing amateur hour think otherwise, please yourself. Take her as a present from me. But just take her. I beg you.’

Costa managed to grasp her arm lightly at the elbow as it moved towards the man. Otherwise, he thought, the moron in the dark uniform would have been in for a shock.

‘You saw this?’ he asked them.

The younger one found his voice. ‘Yeah, we saw it. Hard to miss it. You’d think the kid wanted the whole world to watch. You have any idea what you see if you hang around the Campo day and night? Caught a couple hard at it a few days ago. In broad daylight. And she wants us to start jumping up and down just because her daughter’s got on the back of some guy’s bike.’

The woman shook her head, as if somehow angry with herself, then stared in the direction of the Corso, the way the bike had gone, Costa guessed.

‘It’s not like her,’ she said. ‘I can’t believe this is happening. I can’t believe you people won’t even listen.’

She closed her eyes. Costa wondered if she were about to cry. He looked at his watch. Peroni would be back at the car in forty minutes. There was time.

‘Let me buy you a coffee,’ he said.

She hesitated then put the photo back in the envelope. There was a stack of others there, Costa saw, and he wondered again: was he really letting his imagination run away with him? The girl looked so like the teenager in Falcone’s picture.

‘You really are the same as these people?’ she asked.

‘No,’ he replied, and made sure they heard every word. ‘I’m a civilian. It’s complicated. Even for us sometimes.’

She dropped the envelope into her bag and slung it over her shoulder. ‘Then I’ll take that coffee.’

‘Nice job,’ Costa said and patted the senior uniform on his serge arm. ‘I love to see the carabinieri do public relations. Makes our life so much easier.’

Then, ignoring the torrent of curses directed at his back, he took her arm and led her away from them. She was pleased to go. When her face lost its taut anxiety she looked different. She’d dressed down, in jeans and an old, bleached denim jacket. But it didn’t fit somehow. It was almost a disguise. There was something alluring, almost elegant underneath, something he couldn’t quite put his finger on.

Costa led her round the corner, to a tiny café in an alcove behind the square. There were pots of creamed coffee on the counter, with people ladling spoonfuls into their cups to beef up the caffeine. She leaned on the counter, looking as if she came into the place every day.

‘My name’s Miranda Julius,’ she said. ‘And this is crazy. Maybe I’m crazy. You’ll regret ever asking me here.’

Costa listened as she told her story, slowly, methodically, with the kind of care and attention he wished he heard more often.

‘What’s the matter?’ she asked when the story was finished.

‘Nothing.’

She stared into his face with a frank curiosity. ‘I don’t think so.’

He thought about what she’d said. Maybe the girl really had just run away with a boyfriend her mother had never even met. Maybe it was all as innocent as that. Her misgivings were based on intuition, not fact. She just felt something was wrong. He could understand why the assholes from the carabinieri just wanted to send her on her way.

‘You said she came back yesterday with a tattoo.’

‘Stupid, stupid. Just another reason for an argument. It wasn’t supposed to be like this. It wasn’t why we came to Italy.’ She shook her head and it annoyed him he couldn’t stop watching her. Close up she was older than he first thought. There were stress lines at the corner of her bright, intelligent blue eyes. But they just added character to a face that, when she was young, must have been too perfectly pretty for its own good. She looked like a model who’d later taken up manual labour or something just to make life more interesting, just to get a few scars.

‘What was it like?’

‘The tattoo? Ridiculous. What do you expect from a sixteen-year-old? She had it done a couple of days ago apparently. It was only yesterday she plucked up the courage to tell me, when the scars had healed. She said it was his idea. Whoever he is. But she liked it, naturally. Do you want to see?’

‘What?’

She reached into her bag and withdrew the folder of photos. ‘I took a picture, just for the record. I had the film developed this morning which is why I have all this stuff with me. Taking pictures is what I do, by the way. Call it an obsession.’

She sorted through a set of photos then threw one on the table. It was a close-up of the girl’s shoulder. There was the dark black ink of a tattoo at the top of her arm, and the howling face.

‘You know what that is?’ he asked.

‘She told me. A theatre mask or something. If it was the Grateful Dead I might have understood. She wasn’t that pleased when I said I wanted a shot of it for the record.’

She stared into his eyes with a sudden, determined frankness. ‘I wasn’t taking no for an answer. A tattoo. Jesus, if I’d done that when I was her age.’ She hesitated. ‘Mr Costa?’

‘Nic.’

‘What’s wrong?’

‘I don’t know. I need to call some people. Give me a minute.’

She was starting to look scared.

‘It’s probably nothing,’ he said, and heard how lame the words sounded.