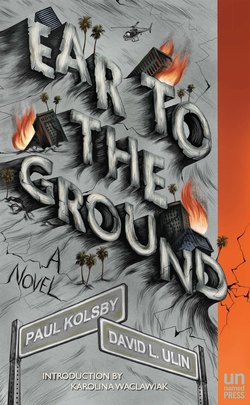

Читать книгу Ear to the Ground - David L. Ulin - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеEAR TO THE GROUND

LOS ANGELES IS THE ONLY MAJOR CITY IN THE WORLD, thought Charlie Richter, heading east on Sunset in his red Rent-a-Corsica, where everybody has to drive. The May morning sun was a laser, confounding even the most creative extensions of his car’s visor, so he looked over at the bus to his right, moving along with him at eleven feet per minute. Its passengers seemed uniformly unhappy, and it occurred to him that Detroit had planned its L.A. marketing campaign carefully. Drive and you’ll be happier.

When traffic began moving freely, Charlie spilled his coffee to the tune of a drop at La Cienega, a splish at Fairfax, and a thwap at La Brea. He took a right—going south—determined to avoid left-hand turns of any kind. La Brea was straight and simple and easy to maneuver one-handed. The red light at Melrose introduced him to a pretty blonde, around thirty, alone in a spanking white Honda Accord, howling with laughter. She caught him noticing and lowered her passenger window. “Howard Stern,” she giggled.

“What?”

“On the radio. Howard Stern.”

The light turned green and he saw no more of her. Turning again, he made his way along Oakwood, past its stucco apartment buildings that appeared to have been shaped from a single mold. He noticed the cracks in their exteriors—at the corners usually, and extending diagonally and horizontally from the windows. Apparent also were the patch-jobs, where wet concrete had been slung as caulk and had discolored quickly.

Charlie pulled into a permit-only zone in front of 418 North Spaulding where, twelve minutes later, he received a thirty-five-dollar ticket. He was, meanwhile, scratching plaster from the house’s front wall with a Swiss Army knife and mixing it on the palm of his hand with a bluish liquid he squeezed from an eyedropper. Satisfied with his findings, he walked around to the north side of the building, looking for a way into the basement. He discovered a crawl space, which, with a shove of the grate, he easily entered.

Louis Navaro intended to rise early and wash his car in front of the building he owned. He had given the Santa Ana winds nearly two days to swirl their desert dust around his quarter-panels and work their insidiousness into his MacPherson struts. A bucket of hot water and a serious gob of Latho-Glaze would stun the demons, and force their retreat. It was his building; it was his car. The woman who’d left him seven years earlier had taken everything else—except for a duplex he’d converted from two vertically stacked apartments, blasting through the ceiling of the lower in a surge so libidinous he was convinced it was the sort of gesture to make her stay a lifetime.

He was wrong, of course, and after two years he moved into a smaller unit on the other side of the building, hoping the duplex would be easy to rent, in spite of its price: twenty-four hundred dollars, firm.

Currently, he lay in bed, staring at a tiny crack in the ceiling that resembled the depiction of a river on a map. He’d had a dream about a cruise boat that sailed, curiously, from Los Angeles to Chicago. The rest was pretty hazy, and no amount of recollection served him. So when at first there was a scraping sound beneath him, he didn’t notice. It persisted, however, and became a pop-pop, then a cack-cack, so Navaro got up. He jumped into some khakis and, zipping up his fly, went out the front door, and around to the side of the building.

Only Charlie’s feet and ankles were visible. Navaro, barefoot and barechested, took note of the exposed black leather uppers and the conservative-looking trouser cuffs. He paused for a moment before he heard from within the rap of metal on metal.

“What’re you doin’ there? Hey!” The rapping stopped.

“Hello? Mr. Navaro?” The voice was muffled.

“Who’s that?”

“It’s Charlie Richter.” It sounded like “Cawa Rawa.” Gradually, the ankles led to shins, and thighs. Charlie’s white button-down emerged, smudged. The expression on his face resembled that of an auto mechanic with bad news. “I was checking the foundation.”

“The foundation?”

“I was wondering why there’s no X-brace along the front.”

“What?”

“Front to back, the expanse is X-enforced, but along the front it’s only an H, and then kind of a …”

“Hey, I’m tri’na find a tenant, not a building inspector.”

“No, I mean …”

“Whaddya afraid of? The Big Bad Wolf?”

Charlie smiled and stood up.

“This building got through Northridge, nothin’ happened.”

“Uh-huh.” Charlie brushed some pebbles from his trousers and looked over at the lawn. “What was your price again?”

“Twenty-four hundred, firm.”

“Two thousand.”

“No way.”

“Tell me,” Charlie hesitated, “how long’s it been vacant?”

Navaro lit a Pall Mall, and spat out a fleck of tobacco. He took a couple of drags and looked his prospective tenant in the face. “This is the only duplex in the neighborhood.”

“Precisely.” This somehow put the landlord at a disadvantage. “Nobody wants to pay that much rent around here.”

“It’s a damn good neighborhood. And a damn good apartment.”

“At twenty-four hundred, people want to live in Beverly Hills.”

“Whaddya need so much space for?”

“My equipment.”

There came the pause that accompanies any derailed negotiation, until one side or the other realigns it. In this case, it was Charlie.

“Here’s what I’m saying. I’d like you to think for a minute about my next offer, and if you can’t abide by it, just say no, and I’ll wish you the best.”

Navaro dropped his cigarette. Charlie, seeing the landlord’s bare feet, squashed it cold, and continued: “But if you say yes, we’ll be in agreement, which makes sense, since we’ll be living under the same roof. So, if it’s all right with you, I’d like you to think carefully before answering.”

“All right.”

“You’ll think about the figure I’m about to give you?”

“Yeah, yeah,” Navaro answered impatiently.

“Two thousand.”

Grace Gonglewski swallowed the last sip of her coffee and put the cup on the kitchen table, in the center of the patch of sunlight that drifted in through the triple row of windows over the sink. She glanced at the script tented beside her, then looked at her watch. Eight fifty-four. I’ll finish this tonight, she thought, and then she let the pages fan themselves shut with a breeze that ruffled the tiny hairs on her forearm. Ruefully, she glanced toward the high-ceilinged expanse of the living room, where two waist-high stacks of screenplays sat next to a white Ikea couch.

Each day at Tailspin Pictures seemed like a lifetime to Grace. She felt, every morning—usually at the intersection of La Brea and Hollywood, where that chrome sculpture reminded her of New York—that she would die in Los Angeles, probably at Warners, reading at her desk.

They wanted her to plow through three thousand pages of screenplay format every week, identifying gems. But God help her (He didn’t) if what she thought was a gem turned out to be coal, or—according to Ethan, two years her junior—shit.

She had not the power to say yes at Tailspin Pictures; neither actually did her boss. Grace lived and marched in the ranks of Development, and it was her job to say no.

If all that was something of a crapshoot, however, Grace’s apartment, at least, was hers alone, created in her own image, where she answered to no one but herself. Looking at the pattern of sun and shadows coming through the curtains, she felt, not for the first time, as if she couldn’t bear to leave. Then she went to get her sunglasses and keys.

The bedroom was mossy, dark, a tangle of sleep smells, crumpled bedclothes and curtains drawn against the light. As Grace’s eyes adjusted, she grimaced at the mess. Sprawled across the width of the queen-size mattress lay Ian, hand raised, as if in protest, against the headboard’s knotty pine. God, Ian—she’d forgotten all about him, although it should hardly have come as a surprise. In three months, they had never once had breakfast together, and lately, she’d even given up kissing him good-bye. Looking at one skinny, dark-haired leg protruding from the sheets, she felt a small finger of revulsion tickle the back of her throat, and she had to fight off the urge to kick him, to tell him to go on home where he belonged. Then she noticed the delicate architecture of his back and, as his breathing rose and fell in small crescendos, her revulsion faded into a shimmering aura of desire.

Outside, the sun was bright but not hot, and morning mist hung like vapor in the air. As usual, Navaro was sitting at the bottom of the front steps, staring at his 1979 Le Sabre as if it were a limousine. When Grace passed, he raised his head and leered at her, sunlight reflecting like lightning off his oiled black hair.

“Guess what?” he said, eyes on her breasts. “I rented the place.”

It took a moment, but then Grace saw the open doorway behind him, and understood.

“Really?” she said. “To who?”

“Some guy,” Navaro explained. He took a quick look over his shoulder before cocking his finger to his ear and moving it around. “He’s a little strange, you know? Asking me about the foundations, shit like that. But hey”—he raised his palms to the sky in an exaggerated shrug—“he paid me three months’ rent, up-front.”

“I’m sure he’ll be fine,” Grace said, not really caring but wanting to be polite. Still, she lingered, the glimmer of a question flickering at the edges of her mind. “He’s not in the entertainment business, is he?”

“Depends on how you define entertainment. He says he’s a scientist, whatever that means.”

The first thing Charlie did inside his new apartment was to hang his suit and dress shirt in the upstairs hall closet. Then he walked off the dimensions of the place, jotting his findings in a blue pocket notebook, and trying to picture how it would look after his machines had been installed.

In the master bedroom, Charlie looked out the windows at the overgrown backyard. Beyond it lay a high chicken wire fence and the back of another house. He didn’t know much about the neighborhood but, Charlie thought, it didn’t matter; the only important thing was that he was here. He could taste the excitement, a flavor in his mouth. He took a deep breath, and another. Then he went into the bathroom and let the old stall shower run.

For as long as Charlie could remember, the feeling of running water on his body had calmed him, had helped him sort out his thoughts and clear his emotions. Today was no different—until he stepped out of the shower only to realize, too late, that he did not have a towel. For a moment, he stood there, helpless, but then he shrugged, and shook himself off like a dog. Water splattered everywhere, fanning out like the cracks left behind by an earthquake … and suddenly, Charlie was seeing the connectedness of the pattern, each drop linked to the ones around it. He closed his eyes and tried to imprint the vision but, like some abstract notion, the floating image would not coalesce.

So Charlie walked naked through the apartment. Briefly, he considered getting dressed, but it was still too early, so instead, he carefully laid out his clothes on the hardwood floor and sat down to meditate. Slowly, painfully, he folded his legs into a lotus position and let his eyes unfocus on a spot across the room. He drifted, but only until a driving bass line began to rumble through the wall from the apartment next door, followed by a fuzzed-out electric guitar, and the steady snap of a bass drum and snare. Although Charlie tried to ignore it, within seconds, there was nothing in his head but noise. Christ, he sighed. Then, refocusing his eyes, he extricated himself from the lotus and went for his clothes.

In the middle of the spare white expanse of Grace’s living room, Ian was in his boxer shorts, rocking back and forth to Courtney Love. He had only been out of bed for five minutes or so, but already the day was beginning to unveil its charms. The bag he’d stashed in the battery compartment of his laptop had yielded exactly one joint, and now he stood smoking and swaying, the sun glancing off his back and legs like a lover’s caress, muscles melting into languid liquid, and the edges of the world going all woolly, as if a layer of green gauze had been laid across his eyes.

Ian noticed the stacks of scripts next to the couch, and he felt himself drawn. A month before, he’d given Grace an old screenplay of his and asked about rewrite work, but although she had smiled and said she’d see what she could do, he’d had the feeling that his request had made her uncomfortable, and he was wary of bringing it up again. He did, however, wonder about the competition, and staring at the piles, he felt his bowels tighten with the incipient thrill of illicit snooping. Grabbing a script, Ian flipped past the title page—Web of Sin—and turned quickly to page one:

EXT. DARK NEW YORK STREET – NIGHT

Let me guess, he thought, I’ll bet there’s a gunshot somewhere in here. He scanned down the page until he found one. Then, nodding to himself in satisfaction, he put the screenplay back, not noticing that the head had fallen off the joint and burned its way through the first few pages, leaving a small, but noticeable, scar.

Ian booted up his computer at the kitchen table and ground some beans for coffee, leaving a residue on the counter near where the filters were stored. He took a final hit off the joint and squeezed the roach into the watch pocket of his jeans, then popped two slices of bread into the toaster. Once the toast was singed brown as a Malibu hillside, he slathered on some peanut butter and began to eat, standing there without a plate, crumbs falling to the floor like flakes of ash.

After the coffee was ready, Ian sat down and adjusted the contrast on his laptop. He was working on a new screenplay, and now he opened up the file, enthralled as the words emerged like magic on the screen. He scrolled back five or six pages, watching the sentences appear and disappear as he retreated to the middle of Act Two. The script was at a critical juncture, he realized, and he’d been working around the issue for days, spinning scenes that didn’t go anywhere, that took up pages and pages without moving the story along. He had his characters together, but somehow they kept walking off in their own directions, and when it came to the earthquake with which he wanted to end, everything he’d written seemed like a cliché.

Man, Ian thought, this is too much. Maybe I should do something else, and start to write when my buzz wears off. For a moment, he just sat there, his mind as blank as the morning light. Then he unhooked the phone and plugged the cord into the back of his computer, making sure to deactivate Grace’s call-waiting before dialing America Online.

At eleven fifty, Charlie entered the ballroom at the Four Seasons Hotel and searched out Sterling Caruthers, who promptly fixed his colleague’s tie by tightening its knot. Already, journalists were scurrying around like noxious bugs, bearing press credentials from newspapers, magazines, radio, and TV.

“Nice of you to join us, Mr. Richter,” Caruthers said, his voice dripping blood. The press conference would begin in ten minutes.

“I’m sorry. I …”

“Never mind.” Caruthers dismissed him with the wave of a hand. Charlie would be seated, he was told, at the far end of the dais, where it was unlikely he’d be called upon to speak. Once there, he began an entanglement with a heavy velvet curtain, which not only obstructed part of his chair but obscured his microphone, as well. He tried pushing the curtain backwards, and then forwards; finally, having no other choice, he slung the thing around his neck and wore it like a shawl.

Charlie’s new employer, the Center for Earthquake Studies, or CES, was endowed with a multimillion-dollar budget rumored to have come about, in part, through a hushed yet symbiotic relationship with the entertainment industry, whose interest lay in the Earthquake Channel, as well as an interactive TV series called Rumble. “If the Big One hits L.A.,” mused an inside source, “the studios will be in on the ground floor.”

There was dissent; the Caltech people were up in arms. The mixing of science with commerce, they claimed, would make it impossible for pure research to take place. Caruthers begged to differ. As CES’s nonscientific figurehead, he’d engaged the services of Gold & Black, a pair of entertainment publicists who had called this press conference and guaranteed a respectable turnout from journalists and other notables—in return for ten thousand dollars.

The first difficult question came from Maggie Murphy of the Los Angeles Reader, who asked Caruthers whether CES had enough scientific vision to warrant spending so much money. Caruthers answered feebly. When pressed with a follow-up, he shot back a question of his own: “How much money is too much?”

“It all depends on what you intend to do with it,” Murphy said. “Do you know that the Caltechies are calling you guys CESSPOOL?”

“That’s their business,” Caruthers announced. “Ours is to develop techniques that will enable us to predict earthquakes with enough time and accuracy to save the city of Los Angeles and other municipalities considerable expense and loss of human life.” He fixed Murphy with a take-that glare.

But Murphy had done her homework. She was Lois Lane with a metallic toughness. “I assume Dr. Richter will be involved in this prediction effort?” Caruthers nodded. “Then why,” she went on, “do you have him over there behind a curtain?”

Embarrassed, Charlie unraveled himself, while a hotel employee held the curtain aside.

“You’re Charles Richter, right?” Murphy asked in a staccato voice. “Grandson of the Richter scale Richter?”

“Yes,” Charlie mumbled.

“And you predicted the quake in Kobe, Japan?”

Camera crews adjusted their positions, and lights were aimed at Charlie’s eyes. He stared into them, looking for a face, but all that came back at him was an aurora of white.

It was true, if not very well known, that Charlie, who’d been traveling for research and for escape, had been in Kobe at the time of the earthquake, giving a paper called “Fault Lines: The Mystery of Plate Tectonics” at a seismographic conference in nearby Osaka. Strolling along the banks of Osaka Bay, shoes in hand and trousers rolled to the knee, he’d noticed something irregular about the tide-flow. After testing water samples, Charlie studied the data—blocks of numbers—and felt a sudden nausea. He took a taxi to a grassy hillock and noticed birds flying overhead in strange configurations. Then he removed a stethoscope from his knapsack and, for more than an hour, kept his ear to the ground. At dinner, he mentioned to a colleague in passing that metropolitan Kobe sat on a tectonic boundary in the process of shifting. Later, drinking Burmese whiskey in his room, he noticed an undeniable correlation between two disparate columns of numbers. He dialed his colleague’s extension and arranged to meet him in the hotel bar, where he explained that Kobe could go at any moment. The man laughed in Charlie’s face and spread the word to some other seismologists, who reacted similarly, behind his back. Twenty-four hours later, no one was laughing.

Maggie Murphy stood now, as did the Times reporter and the guy from ABC. Sterling Caruthers hadn’t opened his mouth in half an hour, as Charlie, blithely sipping from a glass of water, more or less became the subject of these proceedings, deflecting and focusing the debate, explaining technical principles in layman’s terms. Finally, he and Caruthers exchanged a meaningful but complicated glance. Things were winding down.

“What are your present plans, Mr. Richter?” asked Murphy with a smile.

“I go where the promise of seismic activity exists.”

“Yes?”

“And I’ve just taken an apartment in Los Angeles.”