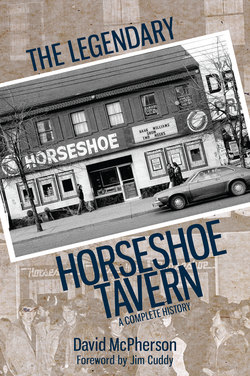

Читать книгу The Legendary Horseshoe Tavern - David McPherson - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

3

ОглавлениеTom’s Stompin’ Grounds

Come all you big drinkers, and sit yourself down

The Horseshoe Tavern waiters will bring on the rounds

There’s songs to be sung

And stories to tell

Here at the hustlin’

Down at the bustlin’

Here at the Horseshoe Hotel

— Stompin’ Tom Connors, “Horseshoe Hotel Song,” from the gold record Live at the Horseshoe (1971)

Drifter, outsider, larger-than-life, and patriotic to the core — there was no one else like Stompin’ Tom Connors.

Many consider the musician to have been a national treasure. His catchy songs with simple lyrics, which are easy to memorize, are still sung from coast to coast by generations of Canadians. Who doesn’t know the refrains to his timeless tunes such as “Sudbury Saturday Night,” “Bud the Spud,” or “Big Joe Mufferaw,” about everyday characters who embody the spirit of our country? Mark Starowicz captured the essence of Tom’s patriotism in a feature for the Last Post in 1971:

I never thought that nationalism was so deeply ingrained in this country until the first time I saw Connors at the Horseshoe. I’ve seen a packed crowd go wild over a singer before, but I’ve never, never seen so much unrestrained joy and applause as when this rumpled Islander got up and started strumming.

Jack Starr (left) celebrates with Stompin’ Tom Connors on the occasion of the Horseshoe Tavern’s twenty-fifth anniversary in 1972.

As the 1960s started to set, making way for the 1970s, the country singer from Skinners Pond, Prince Edward Island, made up his mind that he wanted to perform at the Horseshoe regularly. So he kept coming in and asking Starr to give him a chance. Again and again he’d get his courage up, only to have it knocked down by Starr. But eventually the young musician’s persistence paid off. Jack Starr saw something others didn’t in the fellow outsider.

Today, Connors’s legacy is as legendary as the tavern itself. You could say, for a while, it became Tom’s bar. “Tom made a big mark in that place,” recalls Johnny Burke.

As this chapter unfolds, it will become clear that those eight words of Burke’s are definitely an understatement. Dick Nolan’s biographer, Wayne Tucker, shares the following anecdote that foreshadows Connors’s lasting legacy:

Willie Nelson played the Horseshoe in the 1960s, backed up by the Nolan-led Blue Valley Boys. Dick was around Willie every night and they raised a few glasses together.

The Blue Valley Boys — circa mid-1960s — who were the house band at the Horseshoe, backing up all the Grand Ole Opry stars. From left: Roy Penney, Bunty Petrie, Dick Nolan, Johnny Burke.

One particular time Dick and Willie were chatting over a beer while another performer who was an unknown at the time was on stage. Dick noticed Willie’s mind was drifting and he kept looking up at the singer. Willie said, “Dick, that guy’s got somethin’ goin’ for him. He’s gonna turn out to be somebody.”

And “somethin’ goin’ for him” he sure did have. Stompin’ Tom went on to set attendance records at the ’Shoe that still stand today, more than forty years on. He recorded a gold record (Live at the Horseshoe) and filmed a feature concert film (Across This Land with Stompin’ Tom Connors) in the bar’s cozy confines, and his record of playing the bar for twenty-five consecutive nights is one that is likely never to be broken. Journalist Peter Goddard, who covered many of the musicians and shows at 370 Queen Street West starting in the early 1970s, provides his take on Tom’s Horseshoe legacy: “If anybody could be said to embody the old and the new, the punk of the Horseshoe, it was Stompin’ Tom. He was louder than any punk band. He came at you like a sledgehammer, which was perfect for the place. He was the real thing.… He also foreshadowed a lot of the punk bands that later tried to emulate him. If the Horseshoe ever reached the nadir of its identity it would be with him.”

Connors’s legacy was solidified at Starr’s tavern. As with many Canadian musicians who came after him, the Horseshoe helped boost his career. “These people really like you, Tom,” Jack Starr told Stompin’ Tom in 1969, one year after Starr gave Connors his first gig. Those genuine words of gratitude came only after Canada’s version of the outlaw country singer — who did not fit the mould of the Grand Ole Opry stars who had graced the stage over the previous decade — had proven his worth and gained the Horseshoe owner’s admiration.

The late 1960s ushered in a new era at the Horseshoe Tavern, and Stompin’ Tom led the charge. Like Starr, Tom was an outsider. Bands had a hard time keeping up with his stompin’ foot and his offbeat rhythms. His songs spoke of blue-collar characters: drifters and dreamers like him. That’s why his stompin’ sounds and often silly sing-a-long lyrics resonated with the Horseshoe’s loyal patrons, since the majority of Starr’s regulars came from Connors’s corner of the world: Atlantic Canada. Beyond his fellow East Coasters, Tom would draw a diverse crowd, a motley mix of beer-drinking regulars — from Toronto Maple Leafs fans, to college students, factory workers, and farmhands, to plainclothes police officers. Tom would sing a corny song filled with off-rhymes about Kirkland Lake, Sudbury, or another rural Ontario town, and the Horseshoe’s patrons would holler, hoot, and pound the tables.

“Tom created a conversation,” recalls Mickey Andrews, who played pedal steel with the Canadian icon for years. “He would always have a song about a town that someone from the audience could relate to. He had a different way of entertaining them, drawing out their animal instincts. They weren’t rowdy, but they were boisterous, and the air was electrifying.”

Stompin’ Tom Connors got his moniker due to his penchant for pounding the floor with his cowboy boot, keeping time. These stomps were so heavy that they started to wear out the carpet and floorboards everywhere he performed. Eventually, Tom came up with the idea to put down a piece of plywood — a stompin’ board, which he bought at Beaver Lumber — down on the stage before each show. As he stomped, dust and chips flew into the air. This was all part of the legend in the making.

Stompin’ Tom Connors — who still holds the record for the most consecutive nights played at the Horseshoe Tavern — seen here in a still photo from the movie Across This Land.

The country singer from Canada’s smallest province came to the club owners and concert promoters like a thirsty lion, not a shy lamb. Tom was always his own best PR person; the way he landed the gig at the Horseshoe is a perfect example of this dogged determination. Andrews recalls seeing Tom play at an after-hours club before Starr hired him, and thought he was tipping off the club owner to a new act. Not so. Tom had already gathered up his courage and been to see Starr many times, begging for a chance to play that storied stage. In late 1968, Starr finally relented, giving Connors a chance to prove himself by booking him for a one-week stint. It’s something the late musician never forgot. In his memoir Stompin’ Tom and the Connors Tone, the singer devotes an entire chapter, “Landing the Horseshoe,” to Starr’s bar. In it, Connors recalls the seminal moment when he signed his first contract to play the iconic institution on Queen:

On the twenty-eighth or twenty-ninth of November, I got my courage up again and decided to go down to Toronto and try the Horseshoe Tavern, only this time minus the suit. I really didn’t have much faith in landing a job there because the Horseshoe was known all over Canada. Everybody who was a country fan and who landed in Toronto for any reason, either by plane, car, bus or train, for any length of time, sooner or later, wound up paying a visit to the Horseshoe. The owner’s name was Jack Star [sic] and he had kept the place “country” through thick and thin now for over twenty years and the club had a great reputation. There wasn’t hardly a weekend that went by that the place wasn’t packed, due mainly to the fact that he would always bring a big-name act from Nashville, Tennessee, to play Friday and Saturday night. When Jack finally arrived on the scene I was pleasantly surprised to find that he was a very quiet, congenial man, even though he had the demeanour of a person who knew his business very well. He made me feel at ease and I began telling him what I had done, where I had been up until now, and just how much I wanted a chance to play his club to see how well I could fare. “Well,” he said, “I’m trying out a new house band next week and if you want to come in and see if they can back you up, I’ll give you the opportunity to see what you can do. Bring your contract in before you start on Monday night and I’ll sign you on for a week.

Tom could not believe his ears. That weekend he went back to where he was staying, and that’s all he could talk about with the owners of the house. On Monday, at around four o’clock in the afternoon, he returned to the Horseshoe and just sat there for the next five hours, until his set time at 9:00 p.m. The only interruption to his thoughts came when Starr stopped by his table and asked him for his union contract. After signing it, Starr shook Connors’s hand and said, “You must really want to play here. I’ve been watching you sit there for the last three or four hours, and I don’t think you took your eyes off the stage once.”