Читать книгу Age of Concrete - David Morton - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

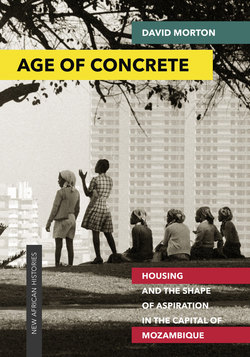

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

You, mother!

Transforming the reeds into zinc

and the zinc into stone

in the wearying battle against time

—Calane da Silva, from “Incomplete Poem to My Mother” (1972)1

IN 2010, about two dozen architecture students at Maputo’s main university were sent into the subúrbios in search of the last of the city’s reed houses. There are many ways to describe the low-lying neighborhoods where most residents of Mozambique’s capital city live, but any frank depiction must underline the fact that, historically, life in the subúrbios has been conditioned by a lack of basic urban infrastructure. For most of the twentieth century, flooding was frequent, and the absence of sewage and drainage lines left neighborhoods vulnerable to cholera outbreaks. To dispose of trash, people had to bury it in their yards or burn it. Very few residents had ready access to running water or electricity. By the second decade of the twenty-first century, however, Mozambique’s nearly double-digit economic growth was changing the picture. The threat of flooding remained, but the water and energy grids were rapidly expanding into suburban households. Many latrines now had concrete septic tanks. Most people were building their houses out of concrete blocks.

A majority of people in the subúrbios once lived in houses built from the reeds that grow beside waterways throughout rural southern Mozambique. The fences of their yards were usually made of reeds as well. But now, even in the neighborhood called Polana Caniço—Polana was a chief’s name, caniço means “reed” in Portuguese—reed house construction, which had been declining for decades, was very rare. The architecture students went to Polana Caniço to record specimens of the elusive suburban reed house before the use of concrete pushed it to extinction. When they found one, they took its measurements and documented it with photographs and architectural renderings, and they interviewed residents about their experiences building with reeds.2

Despite the rustic appearance of the suburban reed house—some might call it a shack—its construction is actually highly standardized.3 Reeds, wood stays, and all the other building materials are purchased at local markets. The basic unit, a low-slung, two-room rectangular structure, is smaller than a one-car garage. The shade of a tree makes the outdoors more comfortable and more sociable than indoors, so daily life—preparing meals, washing clothes, conversing with friends—takes place outside, in the yard. At one end of the yard are a pit latrine and a bathing area, each screened with reeds. As with so many urban housing types, the roof of the reed house is corrugated, galvanized (zinc-coated) iron or steel sheeting. For residents of the subúrbios, the sound of rainfall is a hard, metallic rattle.

To the curious architecture students, the reed houses connected present-day Maputo to a long vernacular building tradition on the city’s margins. “We were trying to learn how they were built so we don’t lose this knowledge,” Maputo architect Rui Gonçalves, who was one of the student researchers, later told me.4 “How can we learn from what we did here, from our own culture, from our own history?” The part of the neighborhood where their professor sent them was a sandy area adjacent to the bay shore and its polluted but popular beach. Gonçalves and the two other students on his research team spent hours looking for reed houses but had no luck. “We started getting desperate. We asked people, ‘Where can we find houses of caniço?’ Most people couldn’t help us. We walked and we walked, until we got to what you could say was the end of the line: a swamp. We felt let down.” But then they decided to walk around the edge of the swamp, and they found an isolated reed house here, another there. Occasionally, there would be two next to each other. The inhabitants of these houses were among the most impoverished people in the subúrbios, living on land where no one else would build. Water lay just below the surface.

When the students asked residents questions, they were happy to answer, but they had trouble finding anything good to say about their houses. Reeds rotted quickly, they said, and the material was expensive to replace. Bare reed walls were no better than a sieve against blustery winds and chilly fog. Living in reeds was almost like dressing in rags. Many residents were already stockpiling concrete blocks. “No one is proud of living in a reed house,” said Gonçalves. Residents were bemused that the students thought they possessed anything of value, let alone a house that they themselves thought so little of. It turned out that only a small number of them had built their own houses; most had paid someone else to do the work. Some had recently migrated from parts of Mozambique where houses were built from different materials. In Maputo, local knowledge of reed construction was once nearly universal. Now, only a relative handful of builders were keeping those methods alive—and only because their customers could afford no better.

Well before the architecture students came calling, the reed house had its admirers. In the 1960s and 1970s, Pancho Guedes, the noted Portuguese architect, would circulate in the subúrbios and photograph the colorful patterns painted on the wood doors and window frames that distinguished some reed houses. Other outsiders who ventured into the subúrbios at the time spoke approvingly of reeds as if they were freely available—as free as the reeds used in houses in the countryside—and good for air ventilation. But the subúrbios were not simply villages transposed to the edges of a city. In dense conditions, where one person’s bedroom might be a few feet from another’s latrine, reeds offered little privacy or protection. Reeds were once so closely identified with the precarious life of the subúrbios that all these neighborhoods were also known, collectively, as “the caniço.”

People of greater means in the subúrbios might use reeds for their fences, but not for their houses. Until the 1970s, they built wood-framed houses clad entirely in galvanized metal panels, and some were quite regal, with lots of rooms, a veranda, and a many-gabled roof.5 Many landlords also built wood-and-zinc compounds, in which tiny units were rented out to the very poor. Wood-and-zinc construction predominated in the oldest parts of the subúrbios so that well into the twentieth century, these districts bore a resemblance to nineteenth-century mining camps. Wood-and-zinc houses stood firmer than reed houses, and the larger models were a mark of status. But this construction method posed its own problems. Termites fed on the wood, and depending on the weather, the house could be unbearably cold or intolerably hot.

Figure I.2 A path in the caniço, late 1970s. (Eva Sävfors)

On the eve of Mozambique’s independence from Portugal in 1975, the subúrbios were home to more than three hundred thousand people, about three-quarters of the population of Lourenço Marques, as Maputo was then called.6 The remaining quarter lived in the central part of town colloquially called the City of Cement—or simply, “the city”—which was then predominantly European (Figure I.3). In local languages, this area continues to be called Xilunguíne, which means “place of the whites,” even though the vast majority of the European population left Mozambique around the time of independence.7 The apartment blocks and high-rises of the City of Cement are not primarily made of cement, per se, but of concrete. Concrete is the more durable substance that results from mixing cement together with water, sand, and gravel or other crushed stone aggregate and then allowing it to cure.8 To be even more precise, the City of Cement is mostly of steel-reinforced, concrete-frame construction with blocks of either concrete or clay used as infill. The name City of Cement has by and large fallen out of use for the same reason that the subúrbios are no longer called the caniço. Since masonry architecture, sometimes just referred to as stone, is the norm in the subúrbios, it no longer distinguishes the haves from the have-nots. Most people now have it.

There was nothing inevitable about the hardening of the caniço into stone. The decades-long transformation of tens of thousands of houses from reeds and wood-and-zinc construction into structures of more resilient materials was a drawn-out but often high-stakes drama and not exactly linear. For a long time and from an official standpoint, everything about the subúrbios was supposed to be temporary, including most people. During the colonial era, the vast majority of Africans in Lourenço Marques not living as domestics in the homes of their employers lived in the subúrbios.9 And until the 1960s, most of them required an official pass for the privilege of living even there. They needed to be formally employed to keep the pass, and many went without one, hoping not to be caught. Few had title to land. Many rented units in cramped compounds. Many others paid a ground rent to a private landowner for a small plot with ill-defined boundaries on which to build. But the rental receipts people stored in suitcases under their beds hardly amounted to anything like secure tenure. In the 1960s and early 1970s, land values spiked, and so did the fear of displacement.

Figure I.3 Maputo in the late 1970s. (Map illustrations by Sarah Baxendale, based on an undated map located at MITADER)

Housing in the subúrbios was not quite legal, at least not categorically. It was tolerated. The municipality allowed reed and wood-and-zinc construction, but it prohibited anything that might hinder future upgrading plans. Thus, with few exceptions, one could not build in concrete even if one could afford to. Beginning in the 1960s, though, many more had enough money to build in concrete, and during the last decade or so of Portuguese rule, several thousand people in these neighborhoods, including a number of lower-income whites, overcame their fears of displacement and ventured to build houses (albeit often rudimentary ones) out of some combination of concrete and clay blocks. In doing so, they risked stiff penalties and possible demolition. I will not be the first to point out the importance to people of building lasting homes on tenuous ground.10 Beyond comfort and beyond status, a permanent house “stakes a claim to belonging” in places that work against it.11 Masonry construction was a political act—a break with expectations that Africans should be satisfied with perpetual impermanence—though it would be many years before most people in the subúrbios felt they could even consider it. The colonial regime, for its part, grasped the power of concrete in uncertain times. The rising skyline of the City of Cement in the 1960s announced to whomever saw it that, despite the wave of decolonization across Africa, Portugal belonged in Mozambique—or, as Lisbon put it, that Mozambique was part of Portugal.12

This book foregrounds what historians usually render as background: neighborhoods of the kind often thought of as undifferentiated, ahistorical slums.13 Each neighborhood in Maputo and each yard is a specific place with a specific past. Taken together, the countless gambles, disputes, impositions, half measures, achievements, and failures inscribed on the landscape constitute an enormous, open-air archive. The book spans the period from the 1940s to the present, but it concentrates on the roughly three decades straddling Mozambique’s independence. It offers a different kind of story about decolonization than the ones that are often told. Strikes, rallies, nationalist appeals, boycotts, armed rebellions—these were the conventional signposts on the way to independence during the twilight of colonial rule in Africa. Epic-scale development schemes and efforts to mold new national identities tend to frame the discussion of how people after independence attempted to uproot colonial-era legacies. And yet, in cities throughout Africa, there were many people who, whether or not they were caught up in politics of a more explicit sort, were engaged in a politics around housing and infrastructure that did not always call itself politics. In this volume, I argue that the house builders and home dwellers of the subúrbios of Mozambique’s capital helped give substance to what governance was and what governance should do. This is especially remarkable when we consider the authoritarian nature of rule under the right-wing Portuguese dictatorship and then the Marxist-Leninist dictatorship that eventually succeeded it. At stake was not just a vision of what a “modern” city should be but also a vision of what a modern society was and what it meant to belong to one.14

Figure I.4 Chamanculo, one of the oldest neighborhoods in the subúrbios, 1969. (MITADER)

Figure I.5 The City of Cement, 1974. (AHM, c-2–4762)

Clandestine masonry home builders were a small, if growing, contingent in late colonial Lourenço Marques, but they were emblematic of a longer struggle to improve living conditions in the subúrbios. Both before and after independence, people attempted to integrate the city’s center and periphery, in part by pushing authorities to acknowledge their neighborhoods and to take responsibility for them. Responsibility, in turn, meant “urbanizing” neighborhoods with infrastructure and adjudicating the many disputes that arose there over tenancy. There are dangers in treating the subúrbios only as a pathology—as problems to be solved—as many policy makers have done; we risk turning these places into mere abstractions and dehumanizing the people who live there. But it is also true that, historically, people living in Maputo’s subúrbios have recognized the conditions in which they live as a problem. They have sought answers, alternatives to the brute-force solution to so-called slums that governing authorities everywhere have reflexively resorted to: clearance.

This book departs from much of the historical scholarship on the built environment in urban Africa in that it further shifts the emphasis from laws to practices; from the architect’s drafting table to the building site; from housing officials and professional planners to landlords, tenants, and home builders; and from government-led projects to places better characterized by official neglect. Yet as a political history, it is not a history from below as that approach is frequently understood. The shape of the city is neither imposed from above nor orchestrated from below.15 It results from the friction of many interests colliding in tight confines.

Scholars often describe the kinds of ground-level interactions that happen in cities as the politics of the everyday because the jostling among neighbors and the tangled dynamic between individual residents and municipal agencies or state authorities do not fit the typical image of what a political contest looks like. In Maputo, the episodes in which these everyday politics were revealed did not feel ordinary to the people who experienced them. Between 1950 and 1990, the population of the capital grew at least tenfold, and there are many people alive today who, depending on their age, have witnessed the population of Maputo and its satellite city Matola increase between thirty and fifty times over, to almost 3 million people.16 This kind of dizzying growth rate since the midcentury is not uncommon for African cities, but it is a fact worth emphasizing for readers who have not themselves lived through a similar hyperexpansion from town to metropolis. We can imagine what such growth meant for those hoping to manage it or for those making a home amid what was a fierce competition for space. Into this same span of time, the people of Maputo compressed the experiences of forced labor, independence, and then civil war, as well as the traumatic results of efforts to impose first colonial capitalism, then a socialist command economy, and then the policies of structural adjustment. One way to look at these episodes is to see how they were reflected in the city’s built environment. But this approach makes it seem as if changes in the cityscape were a sideshow to the real action. Another approach, the one taken in this work, is to see how the making of the built environment shaped people’s expectations and aspirations and how people understood historical change.17 When older residents of the city speak of the more distant past, they are careful to clarify that the city they are talking about is Lourenço Marques, not Maputo. Although the main reason is to delimit the era of Portuguese rule, another motive for the distinction is that, in memory, the neighborhoods where they grew up were, by comparison to today, mato—or “bush.” When some were children, trees and other plants still marked off the boundaries of their yards, if they were marked off at all. The thought is astonishing to people as they recall it today, within a landscape of concrete. Without having moved anywhere, they occupy a different place.

THE UNPLANNED

Frantz Fanon described the typical colonial city as divided brutally in two. One part, the “white folks’ sector,” was “built to last, all stone and steel.” The other part, “the ‘native’ quarters, the shanty town, the Medina, the reservation,” was a place “that crouches and cowers, a sector on its knees, a sector that is prostrate.”18 Writing in 1961, he was justifying violent revolution. But historians of the African built environment limit themselves when they address only how cities were split unequally between colonizer and colonized and, relatedly, the role of European administrators and professional architects and planners in doing the dividing.19 European officials often put great faith in city plans. Some cities were clearly intended as demonstration models of the ruling ideology, with each race in the civilizational hierarchy slotted into its proper place on the urban map. Racial zoning, triumphal boulevards, ostentatious institutional architecture, and housing designed for African workers certainly reveal a lot about what colonial officials and design professionals thought of Europe’s place in Africa. But when scholars continually dwell on a relative handful of government officials and functionaries, it is as if everyone else in the city was a passive bystander. A dream in blueprint is assumed to have created the desired reality on the ground. Projects that impressed their designers are assumed to have impressed their African audiences. Segregation is assumed to have been complete. As Laurent Fourchard argues, if we see cities only from the commanding heights, the history of colonial cities, including South Africa’s apartheid variant, becomes little more than an uncomplicated tale of the colonizer controlling the colonized. The emphasis on schemes imposed from above, particularly on spatial planning based on race, “omits the agency of African societies, their capacity to overcome such divisions, to ignore them or even to imagine them differently.”20 Home builders in the various “native” quarters of the continent were not, as Fanon put it, prostrate. Lourenço Marques was a starkly segregated city, but it was not only segregated.

An important departure from the top-down trend is the work of Garth Myers, who, though concerned with official planning schemes in Zanzibar, also takes care to elaborate how these schemes failed over much of a century because of the continual pushback from Zanzibaris.21 Planners never appreciated people’s deep attachment to long-standing local practices of land tenure and house construction, he argues, with all the meanings for patronage and status these practices conveyed. Myers calls the Zanzibaris’ stubborn resistance “speaking with space.”22 In a similar vein, though in a very different context, Anne-Maria Makhulu calls living in the informal settlements on the outskirts of 1970s and 1980s Cape Town “activism by other means.”23 Squatters may not have been openly fighting apartheid as militants from the African National Congress (ANC) were, but they were challenging apartheid’s premise that their proper place was in a barren rural Bantustan.24 James Brennan’s work on Dar es Salaam addresses another way that politics was mediated through housing: how fraught landlord-tenant relations fed into anti–South Asian prejudice.25 These tensions helped give form, after independence, to a racialized idea of who could belong to the new Tanzanian nation. Each of these scholars reveals the overlapping strata of power cutting through urban societies. Each traces continuities between life under regimes of minority rule and under the regimes that followed. And each explores how the making of urban space constitutes a kind of multilateral politics that has not always announced itself as politics—or even in words. These are also some of the animating concerns of this book. My points of emphasis are different because Maputo’s history was different—peculiar even, owing to some of the peculiarities of Portuguese rule. Still, in the city’s subúrbios, some themes relevant to the histories of many African cities are made more salient.

In African cities, things usually did not go according to plan, but Maputo reminds us that often enough there was no operative plan to begin with—at least not the kind produced by professional urban planners. Once we move past the dispossession and displacement that gave birth to the subúrbios, we find that the suburban landscape is better understood for what authorities did not or could not do there than for the ways authorities imposed themselves. Given this history of official indifference and fecklessness, why begin with government initiatives, when the initiatives of so many households were on such obvious display? People built their own houses not only as a means of survival but also to realize their highest ambitions. And at key moments during the colonial era and since, many people in the subúrbios, rather than cowering in submission before an oppressive state, actually tried to bring government and sometimes even planners into their lives.

The subúrbios of Lourenço Marques exploded in size in the 1960s, just as unplanned settlement was booming across much of Africa and for similar reasons. Like the regimes of newly independent countries, Lisbon loosened urban influx controls in its African territories, and the appeal of cities was strong, even if in many cases this was less because of what the city offered and more because of what the countryside did not. Scholars of urbanization in Africa continue to puzzle over “informality,” a concept intended to grasp all the economic activity outside the gaze of policy makers. As a description of how people in the subúrbios actually lived their lives, the concept helps us very little; in fact, it obscures all the unwritten rules that oriented how neighbors dealt with each other.26 But the distinction made between the formal and the informal does capture a real and long-standing desire for a connection: not just by governing authorities hoping to intervene where they have yet to do so but also among ordinary people hoping that they will. Governance clearly exists at many scales and in many guises, but here I am referring to the kind that only states and municipalities, with their resources and stamp of universal legitimacy, can provide. People in the subúrbios have often yearned for this kind of governance because there is too much that they cannot do on their own or build on their own. When government is absent, it is a felt absence, not freedom. Residents have felt it when there is no active authority either willing or able to provide drinkable water, illuminate dark streets, or guarantee that people can occupy tomorrow the land they intend to build upon today. National authorities, during the colonial era and since, have felt it when, looking upon the living conditions of most residents of their capital city, they sense the emptiness of their own pretensions to leading a modernizing state. Mozambicans have had more reason than most to flee oppressive state power or to resist it.27 But much of the urban politics set in and around the capital from the 1960s through the 1980s cannot be easily described as protest or resistance or opposition to state power. Those who would govern and those who would be governed also reached desperately for one another—usually without success.

This book emphasizes episodes in which people called out for intervention, doing what they could to make their neighborhoods visible to authorities who would not see them or who convinced themselves that the subúrbios were, for the time being, beyond help. In the 1960s, one of the only public debates that managed to emerge in Lourenço Marques, despite heavy censorship, involved black residents of the caniço talking about their living conditions to a daily newspaper with a mostly white readership. Shortly afterward, African nurses at the city’s central hospital developed their own housing scheme for the subúrbios and put it before the municipality. Secret police were locking up people where there was only a whiff of dissent, and yet during a government survey of conditions at the Munhuana housing project, residents had the courage to openly and harshly criticize housing authorities. (All these episodes are addressed in chapter 2.) Even the clandestine masonry builders of the 1960s (discussed in chapter 3), though certainly eager to escape police attention, were in their own quiet way insisting that they were not temporary sojourners but integrated into city life, participants in what they considered a modernizing world.28

Scholars refer to appeals like these, in which people do things or say things that assert a right to be in the city and enjoy the benefits that permanence should entail, as acts of urban citizenship.29 There is some awkwardness in applying the term to late colonial Lourenço Marques. Most people at that time were dubious that being a Portuguese citizen afforded them much of anything. For that matter, we should be cautious in using the word state, as if there were some kind of clearly realized apparatus of functioning institutions to which people could direct their appeals. John Comaroff has said of the typical colonial state that it was “an aspiration, a work-in-progress, an intention, a phantasm-to-be-made-real. Rarely was it ever a fully actualized accomplishment.”30 In some ways, Portuguese authorities in late colonial Mozambique could make themselves felt quite sharply, but in others ways, they were barely there. The same could be said for Mozambique after independence. The Frelimo state was, in many respects, an almost fictive entity needing people to fill it with content and meaning.31

In the years under discussion here, the connections between would-be citizen and would-be state were so faint and there was so little mutual understanding of rights and responsibilities that the effort of seeking government action required a great deal of imaginative heavy lifting. After independence, for instance, as people in the subúrbios attempted to give substance to being new citizens of a new state, they did so in part by acting as if the government were intervening in their lives—executing housing policy and urbanizing neighborhoods—even as the attention of authorities was absorbed elsewhere. This notion may seem abstract for now, but the latter part of the book will develop the idea further. Chapter 4 discusses the 1976 nationalizations of the City of Cement, which triggered the spontaneous nationalizations of suburban properties. Chapter 5 explores official urban planning in suburban neighborhoods during the first decade of independence—or, rather, what looked like official planning. During the early years of Frelimo rule, what appeared to be state-led initiatives in the subúrbios were sometimes carried out by people who were simply behaving as if the state were leading them.32

Some of this fits the picture of decolonization in its narrower sense—the story of a country becoming politically independent—but all of it was part of the process of decolonization in its broadest sense—how people tried to dismantle structures of inequality, both before and after independence. For residents of Mozambique’s capital, the built environment was a medium through which this politics happened because the urban landscape was ever present and unavoidable.33 The material qualities of buildings, houses, and streets—their tangibility, their visibility, their relative fixedness—made construction a necessarily public act. The book demonstrates this dynamic at every opportunity, beginning in the first chapter with a tour of Lourenço Marques, where the density of urban space brought many different sorts of people so physically close together: Africans from around Mozambique, Europeans and South Asians from different social backgrounds, and authorities and those they attempted to govern. Lourenço Marques was defined not just by its divisions, racial and otherwise, but also by the proximities that persisted despite the divisions. The subúrbios, for example, came right up against the City of Cement. After independence, people who occupied abandoned apartments inhabited one of colonialism’s most durable legacies. And the new regime was not just a voice blaring on the radio. The new regime was many people’s landlord.

“Concrete tells us what it means to be modern,” writes architectural historian Adrian Forty. “It is not just that the lives of people in the twentieth century were transformed by, amongst other things, concrete—as they undeniably were—but that how they saw those changes was, in part, the outcome of the way they were represented in concrete.”34 When historians describe societies they know little about, usually because the societies are ancient or not European, they often resort to terms from material culture. They speak of the Stone Age, the Bronze Age, and the Iron Age, and they often struggle with a very clouded view of the choices their historical actors were capable of making. In researching this book, I had the benefit of greater personal familiarity with many of the people I would write about, and yet I was still struck by just how much a single material shaped their expectations and conditioned their possibilities. As this book intends to make clear, it was and continues to be an Age of Concrete.

CHAMANCULO UP CLOSE

Subúrbios does not carry the same meaning that suburbs does in English. In Maputo, the subúrbios have been understood as places previously beyond the reach of urban infrastructure and still largely wanting. Some might object to defining places by what they lack. But this is one of the ways that many people in Maputo understand where they live, and they call these areas what they were called by the Portuguese officials who drew the municipal boundaries more than a century ago and put the subúrbios on the far side of those boundaries. Each neighborhood, or bairro, has its own name and its own history. Because of the low-lying topography of much of the subúrbios, many neighborhood names reflect a waterlogged past. Before drainage canals were built in the 1980s, flooding and disease outbreaks were more regularly recurring calamities in the area once called Xitala Mali—meaning, in Ronga, “place of the abundant waters.”35 Munhuana means “the salty place” in Ronga, and it is so called because of the marshy land there. Lagoas, in Portuguese, means “lagoons.” The neighborhood that features most prominently in this book is Chamanculo, one of the oldest and most populous bairros in Maputo.36 It means, in Ronga, “place where the great ones bathe.” The great ones are the ancestor spirits believed to frequent a creek that once passed through the area. (The creek now only makes an appearance, never a welcome one, during heavy rains.) People have lived in Chamanculo in some numbers as long as there has been a city by the Bay of Maputo. Many of the older men who live in the neighborhood were once employed at the docks and rail facilities down the hill. The railway links Maputo to South Africa’s Rand, the economic hub of southern Africa—a connection that initially provided this port city on the Indian Ocean with much of its reason for being.

In 2011, the municipality started paving Chamanculo’s central artery, revealing some of the bairro’s deeper history to those who were unfamiliar with it. The road, named in the colonial era for a Portuguese physician, had been paved for the first time, hastily, almost a half century before, and by the 1980s, it had crumbled to dust. The new road was to be a more deliberate affair, laid with paving blocks rather than asphalt. Even before it was completed, the road was renamed for Marcelino dos Santos, Mozambique’s independence-era vice president, whose mother, over one hundred years old, still lived in a house in nearby Malanga. Because the road had to be widened from its existing footprint, a few feet or so of space had to be carved out of the houses and yards that hemmed it in on either side. As high concrete perimeter walls were peeled away, one gained a better glimpse into the larger yards where successive generations had built houses adjacent to those of their parents and grandparents. In some instances, one could see, in the cross section of a severed house partition, the rough impression left in plaster of old reed walls that had rotted away behind concrete-block walls, a kind of fossil of the not-so-distant past, before masonry construction was the norm. Homeowners affected by the new road had been indemnified for their troubles (though many said what they received was hardly enough), and at least one family’s house had to be demolished altogether, its residents resettled on a plot on the distant outskirts of the city.37 There was no compensating, however, for the loss of two towering fig trees that were felled to make way for the road improvements. The oldest residents of Chamanculo could not remember a time when the trees were not there. They easily could have been a century old or more, their trunks had twisted together, and they gave permanent shade to what had long been one of Chamanculo’s principal crossroads. Residents call the part of the neighborhood in the vicinity of the fallen trees Beira-Mar, after the long-defunct African football club once headquartered nearby. The team’s wood-and-zinc clubhouse still functions as a bar, but the adjacent practice grounds disappeared in the 1980s when refugees from the country’s civil war were settled there, ostensibly temporarily.

It is testament to the neighborhood’s antiquity and to the long legacy of many families there that Ronga, the language indigenous to the Maputo area, is still the mother tongue of a significant number of residents. According to self-described purists, though, many of the younger people in Chamanculo who think they speak Ronga actually speak a blend of Ronga and Changana, a very similar language that, due to continual immigration from rural areas not far to the north, has predominated in the city since at least the 1960s. People who arrived in the neighborhood from the countryside in the 1950s and 1960s are still considered newcomers by residents who trace their local lineage back still further. Within a five-minute walking radius of where the fig trees used to be are some of Maputo’s most established families. Eneas Comiche is a former finance minister, and in 2018 he once again became president of the Maputo City Council (essentially the mayor), a decade after serving his first term in that office. Some years ago, he worked with members of his family to restore the wood-and-zinc house they grew up in, though all that can be seen of it from the street is its handsome double-pitched roof. It was the house where, in late 1960, the family received Janet Mondlane, the American wife of Eduardo Mondlane, the Mozambican academic who less than two years later assumed the helm of Frelimo, a newly formed movement for independence. The trip was Janet’s introduction to her husband’s land of birth. She wrote to Eduardo of the Comiche house and what she thought it revealed about their friend Eneas. About eleven people lived in only three rooms, she noted. “But the house is as well-kept and clean as a pin,” she wrote. “The children are well-groomed . . . and suddenly I remembered the boy in Lisbon, well-dressed and elegant in his dark blue suit, studying economics. It was here that they grew up, where there wouldn’t be anything without a mother’s love and affection.”38

Ana Laura Cumba, who died in 2012, had lived in a house built by her late father, Frederico de Almeida Cumba, the man who, as the Portuguese-appointed traditional leader (called a régulo), was once perhaps the most feared and reviled African man in Chamanculo.39 As régulo from 1945 until 1974, he made himself relatively wealthy, in part by extracting bribes, and had long before converted a portion of the house from wood and zinc into concrete block. Sometime after his death, Ana Laura rented out much of the house to tenants, keeping one bedroom for herself and another for her traditional healing practice.

Margarida Ferreira, the daughter of one of the régulo’s counselors, lost her house when her husband died; her in-laws simply took it from her.40 But her daughter Graça, who sold clothing, helped her lay the foundations and build partial walls for a new house. Ferreira’s sons also helped. Following the fall of the Berlin Wall, they returned from East Germany where, like thousands of other Mozambicans in the 1980s, they had been factory workers.41 They carried back with them a number of domestic appliances purchased in West Berlin. The appliances were assets. The brothers sold them in Maputo, and the proceeds were used to finish their mother’s walls and install a roof.

Castigo Guambe was living in a wood-and-zinc house, palatial by Chamanculo standards, that his father, a hunter, had built in the 1930s.42 The elder Guambe, who first arrived in Lourenço Marques in the early 1900s, never worked for anyone other than himself, and by the time he died, in the 1960s, he had managed to build a small real estate empire in Chamanculo. About a decade later, shortly after independence, more than two dozen Guambe properties were nationalized by the new Frelimo government, leaving only the original homestead for Castigo and his brother. In the 1990s, Castigo built new rental units and a bar in his yard.

These houses are not mere antiquities. They are not vestiges of a deep past that arrived in the present as the same structures they were when originally built, worn down by the corrosive effects of a process we oversimplify as “time.” The houses and the spaces around them bear the marks of decades of historical change. More to the point, the houses are the change—or at least they constitute a significant part of the story of what change has meant for the residents of Chamanculo over the past century. Each of the houses I have mentioned is an ongoing project; each has never ceased to be a work in progress for the people who have lived in it. Self-built is something of a misnomer, as people have long hired professional carpenters and stonemasons to build their houses. If not self-built in the narrower sense, however, the houses have nonetheless been custom-made to the owners’ specifications. For people on meager salaries or those simply making a little here and a little there, the costs of housing have added up over the years to a massive investment of resources, energies, and anxiety. People hope that their houses will serve as their largest bequests to the generations that follow.43

Buildings and spaces may seem to “say” a great deal on their own behalf, but they do not, of course, actually speak for themselves. A good deal of this book is based on interviews: with residents of Maputo, including a number of stonemasons and carpenters; with current and former Mozambican officials of various ranks, from neighborhood block leaders to cabinet ministers; with several former Portuguese-era officials, including those now living in Portugal and those who are now Mozambican citizens; and with several foreign architects who were attached to Mozambique’s housing and planning agency in the late 1970s and 1980s. Much of the book is based as well on the stories that sons and daughters told me about their mothers and fathers. The interviews were conducted from 2008 to 2016, though they were concentrated during my longest stay in Maputo, from 2011 to 2013. In Chamanculo, I was usually accompanied by one of several research assistants, each of whom was a resident of the neighborhood. They would introduce me to people and translate from the Ronga or Changana on those occasions when Portuguese was not suitable, and they usually were as much a part of the conversation as I or the interviewee was. The interviews were deliberately conversational, wide-ranging, and generally long. I recorded more than 150 conversations, but many of these were with people I kept returning to again and again, and inevitably, many conversations were not recorded at all, including those with the people I stayed with in Chamanculo for several weeks at a time.

The question of housing did not always come up in interviews. In lieu of more substantial historical work on the granular texture of everyday life in Lourenço Marques and Maputo, one must read a number of social-realistic novels, newspaper chronicles, and published memoirs, as I have done my best to do—all part of an effort to grab from the past everything that one can.44 There is no substitute, in any case, for listening to people talk about the past and how they regard their place in it. To ask them solely about housing would have been to foreground housing perhaps artificially. On several occasions, I video-recorded people giving me a tour of their houses. Digital copies of all interview recordings (both voice and video) and transcripts of the interviews will be deposited with the Arquivo Histórico de Moçambique as well as with the architecture and planning faculty of the Universidade Eduardo Mondlane, both in Maputo.

The interviews were a group enterprise of people convened by an American researcher with his own interests; his own priorities; and his own presumptions about house, home, household, and property—presumptions shaped by his own individual experience of the commodified US real estate industry and the marketing of the American “dream house.”45 I have tried not to impose such idealizations on the struggle for shelter in Maputo, such as by highlighting cases only because they conform to prior expectations of what aspiration looks like. For instance, the reader will not encounter a great deal of discussion about architectural distinction—as might attract the attention of an architectural historian—because architectural distinction is not, historically, what most people have aspired to in the subúrbios of Maputo. Rather, they have sought dignified conformity. Additionally, stories people told of making houses in Maputo often silenced the role of women. Women tended to put forward their husbands as the sole spokespersons for the history of their houses. And in the accounts men gave, they tended to exclude the role of women, often a primary role, in the financing of construction—as the significant participation of single women in the colonial-era rental industry helps to make evident. This is to say nothing of the general silencing of the role of women in the construction process itself, as well as in the ongoing maintenance of a house.

This book is mostly about the relationship of a household to its neighborhood, to the rest of the city, and to a state-in-formation. And though I attempt when possible to reveal the internal dynamics of households—much as the best urban ethnographic work does—this is not my emphasis. As anthropologist Karen Tranberg Hansen writes, the intimate spaces of houses are sites of conflict, and a house that for one member of a household signals a great achievement may be for other members of the household the product of their exploitation or unrewarded sacrifices.46 Nor was I able to explore as deeply as I had hoped to the living arrangements to which stigma was attached. A number of compounds in the colonial era, for example, were largely inhabited by women who relied on sex work, in whole or in part, for their income—and decades later, women were hesitant to even acknowledge that they once lived in a compound, whether or not they engaged in sex work. Furthermore, that many of the cases discussed in this book involve a married man and woman ought not lead the reader to assume that this was the composition of most households.

The consequences of not fully examining household dynamics for a project that attempts to explore the politics of housing are steep, since such dynamics are ultimately inseparable from such politics. At the same time, although this book argues that the spaces of the city are more than just the background to other dramas, it must be acknowledged that often and, in fact, usually in the course of daily life, they are mere background. Moreover, the background for many extends well beyond Maputo. People in the city have long maintained ties to rural homesteads, and many women in Maputo (and not a few men) travel to fields (machambas) not far from the city. This fact would be more significant, however, for a work that examines labor and livelihoods, which this book does only minimally. Nor can the book escape the choice of the neighborhood where most research took place. Because Chamanculo is one of the oldest neighborhoods in Maputo, with some of the city’s longest-rooted families, its dynamics are quite different from those in neighborhoods to the north of the city, where very few people lived before the 1960s. People in Maputo’s oldest neighborhoods have had a markedly different experience of colonial rule and independence than, say, people who arrived in the city as refugees of the civil war in the 1980s. And Chamanculo, where Presbyterians associated with the Swiss Mission had a significant presence, developed somewhat different types of social networks than, for instance, the nearby neighborhood of Mafalala, with its significant Muslim presence.

* * *

Though the chapters are organized in rough chronological order, each is thematically distinct, leading to significant chronological overlap. I have tried to avoid forcing a master narrative upon life in Mozambique’s capital; instead, I make use of many smaller narratives, an approach that might be dismissed as storytelling in some quarters. The object here is to reveal the palette of options available to people in history and the invisible frame of constraint—not to establish what the norms and possibilities definitively were (as if this were even doable) but rather to feel for their contours. To relate the histories of individuals with the details of their lives left in is not for the purposes of making dry history more “accessible.” The stories are the evidence.

Figure 1.1 The archbishop of Lourenço Marques surveys the Bairro Indígena after a tropical storm, 1966. (Paróquia São Joaquim da Munhuana)