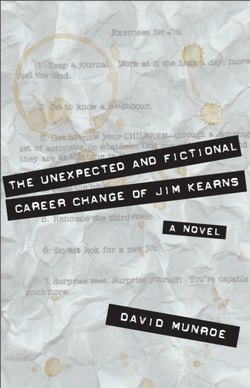

Читать книгу The Unexpected and Fictional Career Change of Jim Kearns - David Munroe - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 1

BEFORE THE INCIDENT

ОглавлениеThe man was typical of the neighbourhood. Tall, straight of limb, with a hint of Aryan smugness, he sauntered across the intersection as if a slight break in traffic hadn’t created an opening for my left turn; and as cars sped up to fill the void, he swivelled his head, stared through the windshield, and arched an eyebrow at me.

“You fucking piece of yuppie shit,” I said, mouthing the words carefully for his benefit. But too late; he’d looked away and slipped into the corner Starbucks.

I looked over at my wife, Maddy. “Did you see that? I should have turned anyway and knocked that asshole right out of his stain-resistant Dockers.”

“Just the asshole, or the whole fucking piece of yuppie shit?” Maddy asked.

“Well ... you know what I mean.” “Yes, I suppose I do,” she said. “Unfortunately, so do Eric and Rachel.”

I glanced at the rear-view mirror. In the seat behind us sat our son and daughter — both beautiful, angelic, and smiling.

“Next time,” Eric said, making eye contact with me, “smack the friggin’ rectum clean out his name-brands, Dad.”

Another gap in traffic occurred. I took advantage of it this time, cranking the steering wheel and accelerating, causing a conga line of pedestrians to stop.The lead dancer gave me what looked like a salute. I ignored him and peeked at Eric in the mirror again. His smile had grown.

“Are you trying to get me in trouble?” I asked. “Because if—”

“Don’t try to pin anything on Eric,” Maddy said.

“Aw, c’mon,” I said. “You heard him — he was mocking me. And it’s all just words, anyway. He hears worse at school every day.”

“But it isn’t just the words, Jim,” she said. “It’s their intent. Not everyone in the world is an asshole, and you shouldn’t be teaching your children that they are.”

A strained moment followed, then she added, “And by the way,you own a pair of stain-resistant Dockers, too.”

“Yeah, but at least mine aren’t khaki.” That was it — my big retort.

As soon as the word khaki left my lips, giggles issued from the back seat — just a trickle, but with the promise of more.

Maddy turned to them and said, “Your father isn’t funny, you know.... Well, okay, he is sometimes. But not this time.”

“Khaki,” I said in rebuttal, turning the giggles into howls of laughter.

Maddy swivelled, looked straight ahead, and muttered, “Three children are just too much for a single mother.” Then she sighed, somehow creating an icy silence amidst the guffaws. I sat in the chill and followed her lead, keeping my eye on the road directly in front of me.

We now drove through a part of the city dubbed “the Estates,” a parcel of midtown land that at one time held historical significance. Five- and six-bedroom houses dotted the area — three-storey Victorians and sprawling centre-hall plans that, come summer, sat under the shade of 150-year-old maple trees. The neighbourhood lay north of the haughty retail strip we’d just left, creating the second leg of a route back from our weekend grocery outing that I found hard to resist. Quicker and more direct ways home existed, but none held the je ne sais quoi of this way.

For the moment, though, I continued to wear the hair shirt, drinking in the neighbourhood with peripheral vision only. Middle-aged women crowned with bandanas and wearing Roots windbreakers conferred with landscape architects about where to place the new season’s arrangements and accessories. The husbands, investment bankers, corporate lawyers, and men of that ilk, clad in crisp jeans and crewneck sweaters, wanted no part of the talk. The weekends they didn’t spend in the office, especially spring weekends, meant action.They busied themselves cleaning eavestroughs and lugging unused firewood from the porch back to the coach house, flexing their well-toned gym muscles.

I looked forward to this drive every weekend, revelling in the opulence: the ivy, the granite, the leaded glass and the oak. And, despite what Maddy may have thought at the time, I wasn’t living vicariously, imagining myself wandering through panelled halls, pulling thoughtfully on my meerschaum pipe as I drifted into the study; or conversely, I wasn’t cruising through this luxury to savour the bitterness of how my life had unfolded. I just liked to ogle.

And luckily, that’s what I’d finally allowed myself to do again; otherwise, I don’t think I’d have reacted quickly enough. As it was, I almost rear-ended the Jaguar flying out onto the road from the circular driveway to our right — with the woman behind the wheel oblivious to our existence. Admittedly, with the tangle of Italian- and German-made vehicles blocking her forward progress, she had limited options, but she might have considered a shoulder or rear-view-mirror check as she backed onto the street with the abandon of an Arkansas moonshiner.

Consideration of any kind, though, hadn’t landed her in the Estates; so we sat motionless for a moment, almost bumper to bumper in the middle of the road, as the woman, still unaware of our presence, struggled to slip her automatic gear shift from reverse into drive. I touched the horn and she turned her head. Instantly, equal parts surprise, contempt, and consternation registered on her face: not only was she astonished to find someone behind her, but what the hell were the Clampetts doing in her neighbourhood?

Then, shrugging us from her consciousness, she turned and drove off. As I reaccelerated, Rachel (in a passable upper-crust voice) commented from the back: “I say, it must have been the chauffeur’s day off.”

Eric continued with the same clipped enunciation. “And she simply had to get to the spa and have more platinum dye rubbed into her hair before she started regaining IQ points.”

Maybe it was just a father’s pride, but I thought they were funny, and I couldn’t help but notice that they held a feel for life that belied their ages.

Maddy agreed — but not quite in the same way. “Doesn’t anyone in this car think that those statements were a bit cynical, a trifle jaded, for twelve- and thirteen-year-old children?”

“I thought they were witty,” I said,“for ... young adults.” “Really,” Maddy countered.“So am I going to have to be the only mother in the world who’s forced to take her son and daughter aside and tell them to stop making fun of the more fortunate?”

At this point I might have suggested that they were trying to lessen the sting of deprivation through humour, but they’re not at all deprived so I said nothing.

For a moment no one did ... until Rachel filled the dead air. “Oh, no. It’s not like that at all, Mom,” she said, cheerfully. “We enjoy making fun of the equally fortunate, too.”

Then Eric, with obvious feigned chagrin, applied the coup de grâce.“And the less fortunate.” Another hush fell over the car until he continued — again with the privileged accent, “They’re khaki!”

Once more hoots of glee echoed from the back seat, but I couldn’t join in. I clamped my lips shut, trying to stifle the laughter, and immediately fired a plug of snot from my right nostril. It hit the outside of my right pant leg and stuck, glistening, like a bright green garden slug clinging to a leaf.

And that’s when I sensed the initial gust, I suppose. Normally Maddy would have responded to my misfortune, maybe with a belly laugh, some pointing, and a hearty “Hey guys, look at that!” But this time nothing, not even a look of contempt — only a reapplication of silence.

Whether she’d actually started planning the changes to come at that moment or just wallowed in the urge to do so, I couldn’t say, but she didn’t speak for the rest of the trip home.

Home.

The word itself is worthy of a paragraph — and much more. It’s where the heart is; it’s where you hang your hat; it’s where you can’t go back to again (okay, so that’s a bit convoluted, but you get the drift). Figuratively, it’s many meaningful things; literally, it’s where you live.

Maddy and I have lived on Linden Avenue for seventeen years now (an accomplishment I still find amazing) and witnessed its most dramatic changes. When we first moved here, as a youngish married couple in the mid-eighties, the area was a predominantly Scottish enclave — as hard as that is to believe, or even detect, for that matter. Tidy green lawns fronted bungalows and detached two-storey brick homes with mailboxes that read Lynch or Tiernay. Often, a single initial, a stylized M, would grace the aluminum grill on the front screen door of a neigh-bourhood home, subtly representing the good name of the Macphersons or Macdougals or Macdonalds within.

As I stated, why Scots had come to populate this area, built during a boom in the mid-forties, is hard to figure. With other cultures and nationalities, you can pinpoint the sudden need for migration: potato drought, persecution, the horror of genocide. But Scotland? Had a post–Second World War candy shortage befallen the country and the history books failed to record it?

Whatever the reason, the Glaswegian Bakery, a purveyor of small, spartan-looking pastries over on Kendall Avenue, demonstrated the only hard evidence of the existence of this otherwise almost indiscernible ethnic group. When Maddy and I first moved into the neighbourhood, throngs of aging patrons filled its aisles every Saturday morning, accchingg and ayeing to each other, clutching their change purses, and looking to satisfy any remaining sweet tooth with bonbons from back home.

The bakery faded away some time ago, as did most of the Scots (to their graves or old-age homes), and their children have grown up and moved on to build their own lives, but Maddy and I have stayed put — through all the booms and busts in real estate and the shifts in sensibility around us. Over the years (the last few in particular) the change in the landscape has been shocking, as, one by one, properties have changed hands, and the golf-green lawns and discreet shrubberies of Linden Avenue have given way to terraced rock gardens, wildflower explosions, and pastel picket fences.

And that’s just what I see now whenever I look across the street: a pastel picket fence, the colour of a clear midday sky. Behind it, a huge oaf of a dog named Apricot patrols a blanket of red wood-chip ground cover at any given time of the day. Some kind of Ridgeback/Lab mix, she weighs maybe 120 pounds and could easily knock the fence over with one good ram — but that’s not her style, her raison d’être. Apricot’s a greeter; propping herself up on the fence with her front paws, she waggles her enormous butt and tries to lay her washcloth of a tongue on anyone brave enough to stop and say hello.

I like Apricot and often do stop to say hello to her. About her masters, though, I know little.The wife and mother in this unit, Ashley, is still young enough to be pretty and fit. She drives their Honda Accord downtown every morning, where she does something much more than secretarial (although I don’t remember what) for a major insurance company. The husband and father,Wendell, has written a critically acclaimed short story collection (now there’s a profession for you — he might as well have penned some top-drawer poetry, too) and is in the midst of contemplating another one. What he really does, besides lugging cases of beer into the house on Friday nights and looking cool, I’m not sure. And their two-year-old boy, Casey, is as precocious as a child can possibly be without crossing the border into obscene.

I don’t know; maybe I’m being a bit unfair. Maddy’s had coffee over there a few times and swears the whole damn family’s as pleasant as they appear to be — and that Wendell’s poised at the doorway to literary success. My response to that is this: Writing short stories? What fucking doorway’s that? The one with the wino sleeping in it? But I keep it to myself because I don’t really know him (and I do know Maddy).

At this point, I can safely say I don’t really know anybody on the street anymore, because somewhere between the last bust and boom, we’ve had about an eighty percent turnover rate.We may not be the Estates here, but the grossly inflated real estate prices of the past couple of years have created a kind of real-life Monopoly game: we’ve been sitting on St. James Avenue for our entire married life, and the people around us have just moved in at Marvin Gardens prices.

This is good for our finances, I’m sure; whether it’s as good for the street as a whole, I don’t know. My practical side says it doesn’t matter.We still have to crawl through the same old maze and react to the same old stimuli — we just rub shoulders with different rats now; another side of me, though, a side that taps into my childhood, asks this: What about continuity, familiarity, and trust? People today invest in houses and areas, but do they live in homes and communities?

And then there’s another side still, the one that tells me to grow up. When have I ever known a neighbourhood to be an actual neighbourhood and neighbours to be true neighbours? The last I knew,Ward and June Cleaver were fictional characters, and television cameras rolled when they gathered around the dinner table to serve up apple pie and Christian insight to Wally, the Beaver, and the Great Unwashed.

At our dinner table, Maddy and I always reach our limits at the forty-five-minute mark.This isn’t an approximate thing; we time it, and it arrives every evening like clockwork — except on pizza night.All food and beverages are consumed, and all cleanup complete, within half an hour on pizza night.

But that evening in particular, steaks, congealing and still barely touched, lay on Eric’s and Rachel’s plates as minute thirty-eight popped up on the microwave clock. As usual, we sat in the kitchen — not out of any Rockwellian tradition, or in the hope of exchanging casual information about our busy days, but out of necessity. If we threw a TV and comfortable seating into the mix, the kids would never finish supper.

“Meat is murder, y’know,” Rachel said, breaking a lengthy silence. She grimaced as she poked at the drying brown slab in front of her.

“Was that The Smiths or The Cure?” I asked, looking to Maddy.

“The Smiths, I think,” she said. “You sure it wasn’t Al Jolson?” Eric asked. The mood was still light enough and wouldn’t get truly ugly for a few minutes; we had one or two more steps to follow in the intricate Kearns/Moffatt dinner ritual.

I stood, scooped up Maddy’s and my empty plates from the table, and carried them to the sink.“That’s not informed enough to be an insult, buddy boy.You’re two generations off.”

“You never answered my question, Dad,” Rachel said.

“You never asked one.”

“No, but she did voice a concern,” Eric said, and I could sense a looming snootiness in his tone, as if he thought he were about to score points. “Our generation does have some. And here’s another: mad cow disease.” He now eyed his steak as if it were reprehensible and pushed it away.

With the dishes safely in the sink, I turned and leaned against the counter’s edge. “Whoa,” I said. “I’m not even going to touch that one.”

Eric looked at me, all innocence. “Why not?”

“Just because, that’s why.”

“But he’s got a point, Dad,” Rachel said, poking at her wilting salad. “Mad cow disease is a serious health issue.”

“No. It was a serious health issue at the beginning of dinner,” I said. “Now it’s just another attempt at one of your last-minute suppertime bailouts.”

“And if you must know,” Maddy added,“your father picked up the steaks at the Big Carrot.They’re organic.”

Instantly, both children spewed laughter. Finally, Rachel managed to say, “You mean Dad actually went shopping at a health food st—”

“Oh, you find that funny, do you?” I said.

“Totally,” she said.“I’m just trying to imagine you clumping around the Big Carrot’s aisles in your work boots, squeezing the tofu and—”

“Well, here’s what I find funny,” I said, cutting her off again (now fully stung by her stereotyping).“Both of you would eat a hamburger ... no, scratch that, both of you would gobble a banquet burger and a side order of chili fries without a single mention of health issues or animal rights, but when we stick a proper meal in front of you, both of you bleat and bellow like ... like mad cows yourselves.Your arguments aren’t consistent.” I blew out a breath, winded by my own bullshit, tossed my hands in the air, then added,“And y’know what else? I should have picked up some tofu. Watching you guys try to eat it would have given your mother and me a few dinner table laughs.”

Not even the clink of cutlery cut the ensuing silence, and Maddy seized the opening.

“Well, once you get past his delivery,” she said, glancing at me, “your father’s right.You need variety — which means you can’t just stick to fast foods.And let me tell you. Both of you will be sorry five years from now if you cheat yourself of your full physical potential. So much of how you feel about yourselves is going to hang on that.”

And so, pretty well on schedule, our version of dinner theatre slipped into its third act: she’d uttered the full-physical-potential monologue. Both children bent over their plates and started sawing off morsels (a knee-jerk reaction that would last for one mouthful) while I still hovered around the sink, contemplating the great circle of life. Roll back the clock thirty-odd years and I’d be the one pinned to the table.

The one difference would be that my mother and father mostly worked the guilt angle. In my day, when I contemplated the shrivelled pork chop or cluster of ice-cold greenery that had been congealing on my plate for close to an hour, my parents would fall into cross-talk routines, ranging from the patented “We bend over backwards for you and what do we get in return?” speech to the impassioned “How do you think a child in Biafra would respond to what’s on your plate?” lecture.Apparently, children there would wrestle each other to the dry, cracked turf for a single Brussels sprout, snapping twig-like appendages in the process.

I looked at the microwave as 6:47 transmuted into 6:48. We’d started at 6:05. Time marched; finger-wagging and then sanctions (lifted almost as soon as they’d been imposed) loomed. So, with images of my childhood dinner table ordeals still fresh in my mind (along with the pang of being labelled socially one-dimensional), I spoke.

“Y’know,” I said,“there are kids in Biafra who’d literally kill to get what’s on your plate.”

“Bi-whooo?” Eric said.

“Bi-whaa?” Rachel said, almost simultaneously.

“We’ve got three hundred television channels, you can make reference to Al Jolson in your conversation, but you’ve never heard of Biafra?”

“Uh, Jim,” Maddy said. “Maybe that’s because there’s no such place as Biafra.”

“What do you mean? Biafra! Y’know, the country where hundreds of thousands, maybe millions, starved to death back when we were Eric and Rachel’s age.”

“As far as I can recall,” Maddy said, “Biafra was a part of Nigeria that reverted back when their civil war ended — in the late sixties ... no, 1970, I think.”

“Exactly,” I said.“Yes. Nigeria ... that’s where...”

“Aha,” Eric said, pointing his fork at me in an annoyingly adult way (I had no idea where he picked up the mannerism). “You didn’t know that interesting little fact, did you?”

Of course I didn’t, but before I could utter any logical response, I said,“ I know plenty, pal ... like, what do you call five hundred Biafrans in the back seat of a Volkswagen?”

“Jim!” Maddy said.

“So? What do you call them, Dad?” Rachel, as tone deaf as children sometimes are, looked at me expectantly.

I glanced over at Maddy, torn between my two gals, if that’s not being too melodramatic, before going for the laugh: “Corduroy upholstery.”

The kids looked at me with vacant expressions.

“I guess you had to have been there,” I said.

“Okay, you two can go now.” Maddy nodded at the children and I peeked at the microwave; we’d sat at the table for forty-five minutes exactly.

As they left the kitchen, she called out: “But you both have to eat a bowl of cereal and some grapes before bed tonight.” They slipped away without response, leaving us alone, yet somehow I suspected fingers would still wag — right on schedule.

“I wish you’d quit doing that,” she said, as soon as the footsteps had faded.

“Quit doing what? I was just trying to get them to eat.”

“I’m talking about the Biafra reference.”

“I’ve never mentioned Biafra to them before in my life.”

“That’s obvious,” she said. “But don’t avoid the real issue. What I mean is, you’ve got to quit teaching them that misfortune, misery, even tragedy, is funny.”

“But it is,” I said.“Tragedy’s a basic building block of comedy. Stepping on a banana peel may be a cliché, but only through overuse; the concept itself is still hilarious.”

“Sure, unless you smash your brains out in the fall and leave behind a wheelchair-bound widow and two infants. It’s not so hilarious then, is it?”

“That,” I said,“would depend on the context.”

“No, that outcome could never be funny — like Biafran jokes told to the children at our well-stocked dinner table could never be funny.”

She spoke with what was becoming a familiar stiffness, one that implied that she was right and I was wrong and nothing I could say would change her mind. My last and only stratagem now had to be esoteric — victimless.

“What about those two masks,” I said, going for the big stretch. “You know, the ones for the theatre that signify comedy and tragedy; they’re always shown face to face — an inseparable pair. Come to think of it, don’t they always seem to be entwined somehow...?”

By this point in the conversation, though, any exchange of ideas with Maddy, esoteric, concrete, valid, or otherwise, was futile; she was pissed.

“Let me tell you something, hubby dear. We’re not going to wind up face to face tonight as an inseparable pair ... and we’re sure as hell not going to be entwined somehow.”

Luckily, my initial response of “Oh boy, doggy style” stayed in my head, because eventually she lifted that sanction, too, and we did wind up face to face, inseparable, and en-twined that evening.

But thinking back, I’d missed another sign; it was just a small precursor to the current situation, though, and sometimes the odd thing slips by you as you perform the complicated task of living your life.

To a large degree, when you’re born dictates how you’re going to live your life (genetics and locale being the two other main factors, I would think). Regardless of our present-day threats, enter the world during the fourteenth century, say, and life’s a far bigger gamble than it is now — maybe you’d hit sixty, or maybe appendicitis or a mouthful of gamy pheasant would take you out at age six. And whether a pauper or a noble, you wouldn’t stand in front of the toilet in your pullups, giggling with delight (as any sparkling-eyed three-year-old would these days) while you watched the porcelain portal magically whisk away your poo poo.You’d shit into a communal trench (the royal hole or the serf ’s ditch), gagging at the stench bubbling up between your pudgy thighs as you added to the rancid pile.

I was born in 1957 — right here in good old North America. With Enrico Fermi’s job complete and Jonas Salk just dusting off his hands, not a bad time and place.Yeah, threats existed, but the postwar economy chugged right along, and whatever came our way we sure as hell could handle. My parents, one a paper pusher and one a homemaker (as was the style at the time) were a pair of robust, mentally able WASPS who dealt reasonable hands to all three of their children. So, regarding those variables affecting quality and quantity of life, I had no right to complain.

I did grow up in another city, though, a government town, which meant I saw little in the way of industry or big business as a youth. To me, politicians were the norm — and most of them, if not on the take, were guilty of collusion or nepotism (if you heard the whispers), or just plain stupidity (if you heard them speak).

Their forefathers, mustachioed gents of old, had decreed that no building erected shall be taller than those buildings housing bodies of government, and a tower with a clock in it did dominate the stubby skyline (a pointy, phallocentric thing rising some 302 feet), an obvious self-tribute to the swaggering, belligerent dicks running the show.

Nevertheless, the city had its charm: in the summer it was lush and green, and a manmade canal — an impressive physical accomplishment for early-nineteenth-century engineers —wound through its centre. What the canal’s original function was meant to be, I couldn’t tell you, but its main twentieth-century duty appeared to be carrying armadas of sightseeing boats (with payloads of camera-toting tourists dropping their coffee cups, Wrigley’s wrappers, and Marlboro lungers into otherwise pristine waters) through some of the older, prettier residential sections of the city and into the downtown core.

In the winter (after the locks had been opened, draining vast amounts of water into the big river north of town) the canal transformed into a six-mile-long skating rink — touted as the longest in the world. With five-foot-high walls of cemented-over masonry now exposed on either side, and the walking path’s milky-globed lampposts casting silvery light from above, the ribbon of ice coursing through the city held a dreamlike quality on those cold, snowy evenings. And on the weekends, thousands of rosy-cheeked recreational skaters filled this rink, the adults gliding shoulder to shoulder, the children weaving in and out of traffic, engrossed in frenetic games of tag or snap the whip. Viewed from the path above, the masses seemed to perform an intricate, choreographed dance as they propelled themselves to the next hot chocolate kiosk or chuck wagon stand or port-o-potty.

The canal was one of the few highlights, physically or spiritually, of my birth city and childhood home. I grew up next to it (or, more correctly, to a small inlet called Richelieu Creek that jutted from it like an afterthought in the middle of town) and it’s what I remember best.

The inlet itself lay at the bottom of a shallow hollow between my street and Baymore Terrace and gave the impression, at first glance, of a natural waterway cutting through a miniature valley. But upon closer inspection you could see the original flag-stone mason work, almost two hundred years old, rising just above the waterline. It ran for six hundred feet and, over the years, as housing and roadways and civilization in general sprang up around it, necessitated two quaint arched bridges to link the sprouting thoroughfares. Cobblestone walkways and sprawling greenery lined both banks of the creek, and intricate wrought iron railings were added to it to keep the locals from falling in.

What never entered my mind as a youth (but always has when I’ve thought back on it as a shovel-wielding adult) was the amount of labour that must have gone into building such a beautiful but unnecessary elaboration. Even using draft horses and whatever hauling machinery they might have had back then, it must have taken fifty men at least two hundred days to produce something that held no real value to anyone; they’d even left a small island in the middle of it — a ten-by-thirty-foot oasis abounding with trees and wild foliage — as a kind of salute to its frivolity.

But whatever its original purpose, or lack thereof, the creek left me with a stunning hangout as a youth. Standing in that small strip of lush parkland at dusk and looking at the sprawling heritage homes of Baymore Terrace from beneath fairytale lighting almost took my breath away; well, maybe the view and the cigarette dangling from my twelve-year-old lips did that together.

I don’t know if you’d call it a parable that I can remember my first drag on a cigarette taking place in that Eden-like setting. Truthfully, I don’t remember my first cigarette at all, but the first cigarette I do remember (my first taste of the forbidden fruit), I sucked back in that very spot. I just didn’t have Eve by my side.

I partook of that particular mistake with a fellow preteen named Stanley Austen. Stanley was one of those saucer-eyed, floppy-eared, chinless marmots who looked like the subject of either a seventeenth-century English painting or a Jerry Springer episode on “Ozark Mountain love-tryst aftermaths.” You don’t seem to see as many of his type as you used to — the relatively recent advent of trains, planes, and automobiles has broadened the gene pool enormously over the decades — but he was a nice guy and my close friend back then.

That event, that premiere, I guess you could call it, took place in a what seems like a different life now — more than a hundred thousand cigarettes have passed my lips since — and even though I’ve filed much of my childhood under “things to forget,” I clearly remember that particular moment in time.

It was late fall, I know, because a carpet of red and orange leaves hugged the creek’s terrain; glazed with autumn condensation, they didn’t scatter but hopped forward in clumps when you kicked them, and they sparkled as if on fire beneath the park lights — which were already aglow although it was barely five o’clock.

Stanley and I hadn’t even made it home from school yet — we’d waited patiently for the cover of darkness before, paradoxically, wandering over and parking ourselves on a bench under a lamppost. (Today, two twelve-year-old boys sitting on a park bench after sunset would be targets for six kinds of perverts, a Reebok robbery, and a couple of good old-fashioned beatings; of course, it could have happened back then, too, but parents and children seemed far less aware of the possibilities.)

So there we sat, totally unaware of what ramifications lay on the other side of the doorway we were about to jimmy open into the future even as we discussed what we thought was the most insightful fact about the impending act.

“If you smoke it right down the filter,” Stanley said,“ you get lung cancer instantly.”

“Wow, are you a fucking moron,” I said. “Cigarettes don’t cause cancer. Both my parents and three of my grandparents smoke and they’re all still alive.”

“Well I guess they never made it to the filter then,” Stanley said, indignantly. “Most people don’t. But go ahead and smoke yours right down, a-hole. I really hope you do. I won’t do any crying at your funeral.”

Stanley had previously informed me that hemorrhoids were nothing more than a painful buildup of shit. A quick check of the Preparation H package in my parents’ medicine cabinet straightened me out, so I no longer deferred to his medical knowledge — but I did tell him never to mistake any anal ointments for Brylcreem lest he lose, or at least substantially shrink, his mind. Still, he’d given me something new to think about on the smoking front — although I wasn’t going to tell him that.

“How about you produce them first, turd breath,” I said, with forced bravado.“ Then I’ll smoke mine right down.”

And so he did, drawing from his jacket two cigarettes that he’d pilfered from his mother’s pack at lunchtime that day. Tobacco had shaken free of their tips, and from their long stay in his pocket they’d bent at the middle in what almost looked like polite, oriental bows; but to me, they looked every bit as straight and full and promising as the television commercials claimed them to be.

We stood and stepped right next to the lamppost. Standing beneath that cone of light, with his collar turned against the autumn wind and an unlit smoke clamped between his teeth, Stanley looked like a young and ugly Humphrey Bogart. And me? Maybe I looked a bit like a youthful Steve McQueen, although Maddy might smirk at that notion. But, hey, apparently Steve had to work at hiding a lisp, and he really wasn’t that good-looking.

It’s all about image. Stanley and I knew this even then as we sparked up his mom’s Virginia Slims.We looked tough, manly.

The taste, the smell, the park, Stanley: memories are made of this. Specks of time that litter your mind, tiny parts of a vast sum that you can never come close to totalling; if I remember correctly, neither of us smoked it right down to the filter, although I can only vouch for my actions and the sheer nausea I felt.

But with the nausea came a delightful lightheadedness that was either a lack of oxygen, instant addiction, or an intoxicating combination of both. And, of course, smoking really did make us look manly.We saw it in each other through tear-filled eyes as we sucked on those nipple-like Slims.We’d come a long way, baby.

How far have I come since then? It’s a trip I can’t measure in time or distance; well, okay, I can. I’m forty-five years old and I’ve moved a couple of hundred miles down the highway from my hometown, but the true measurements lie in accomplishments and relationships.

And in those terms, one year rises above the rest: 1982, the year Maddy and I drifted into the same house on Dalton Avenue through some kind of degree-of-separation unfolding — months apart, both of us replacing a friend of a friend who’d flitted off to some new development in life and left news of a cheap place to live.

The complete roster in that place usually totalled six students — three men and three women, following a sex-preference screening process that Adam Wright, the fourth-year arts major holding the rental agreement, faithfully employed. His official statement was that the fifty-fifty gender split made life less complicated, but six young adults of any gender placed under the same roof made for complications galore.

The house was a big, rundown, five-bedroom monstrosity — a quasi-slum at the edge of the Annex but close to the university’s downtown campus. The tenant turnover rate there depended on semesters, employment status, and other variables — such as who was getting together or breaking up with whom. Much of the thinking and mood in the house was testicular and ovarian in nature.

I’d lived there for five months and had recently dropped out of school (for the second time in four years; as much as I wanted to, I couldn’t grasp the importance of Democracy in America at all, and I thought the existence of Jean Paul Sartre made France’s worship of Jerry Lewis understandable). Still, life was good. Women like their men either brawny or intellectual — although I suppose they’d prefer both, with a dollop of sensitivity thrown in for good measure — and I’d landed a job as a labourer. By June of that year, I was as bronzed as I’d ever been and these strange ridges, triceps, deltoids, and the like, had sprung up all over my body. I was no Arnold, but I was more of me than I’d ever been in the past.

That entire summer, heat pressed down on the city. On weekdays I moved double-axle loads of crushed rock with a Bobcat; and when the front-end loader went off-site, three days minimum of each six-day week, I stood in the sun and battled that eighteen-ton hill with nothing more than a shovel, a wheelbarrow, and orders to move the entire pile during the workday or move on to another, less demanding, line of work. How’d that old Tennessee Ernie Ford song go? “Move sixteen tons and what do you get...” The tune used to burst from my lips in an off-key whistle every once in a while as I flailed away at that crusher run.

In retrospect, how a young dirt digger could feel happy and even the slightest bit bohemian is beyond me, but somehow I managed. On weekends the house didn’t close.A group of people could drop by at any time, toting with them a few grams of hash and a huge haul of beer, with someone in the crowd holding My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, the new Eno/Byrne album, or maybe John Cale’s latest release.

One night in particular, Adam stepped into the living room waving a fistful of tickets to an all-night Lina Wertmuller fest at the L.A. Theatre. A uniform and heartfelt groan echoed throughout the room (with the sparse Goodwill furnishings doing little to absorb the sound).

“Why in hell would you expect anybody to go with you to that?” Katie Jansen asked.

She sat beside her sister,Audrey, who, at one year older, held one more year’s worth of opinions; otherwise they were twins. They hailed from somewhere hard and flat and cold in the middle of the country (but lived in a permanently loud state wherever they travelled). Of Nordic decent, strapping and rosy-cheeked, they wouldn’t have looked out of place in pigtails and leather shorts,The fifth tenant at that time, an engineering student by the name of Nick Burke, had pulled his usual weekend disappearing act, flitting to a better part of town and a better calibre of acquaintance — so what we had there (although, mercifully, no one ever said it) was the gang.

“It’s not where you go, it’s how you go,” Adam said, reaching into his pants pocket and removing a baggie. He pulled a length of Thai stick from the plastic and threw the grass onto the coffee table. Composed mostly of flower tops, it was tacky and ripe enough to stick to its skewer unaided; its pungent smell filled the room immediately.

“All right,” Audrey said. “Even Lina’d be funny after a few hits of that.”

“But wait ... there’s more,” Adam said, in his best game show host impression. He dug into his other front pocket; another baggie hit the table. “Mushrooms — the West Coast’s finest. Something to nosh on and kill those munchies, and that dastardly edge, after we’ve smoked some of this weed from hell.”

So we smoked and noshed, and although none of us young, sensitive types would stand for drunk driving, we climbed into Adam’s ’71 Vega, a deathtrap with a hood that loved to fly open at inopportune times (with obstructions as jarring as road paint being a possible catalyst), and started for the L.A. in a haze.

Two blocks later, Adam pulled over.“ Every light’s green, yellow, and red,” he told us, although I’d been seeing different colours altogether.“ I’m afraid the rest of the way’s on foot.” We spilled out, making it as far as the Saint Vincent House Hotel before common sense took over. Neither road nor sidewalk would have been a safe place by that time.

The Vince was our normal hangout, anyway — a two-hundred-seat bar within walking distance of the house that featured floor shows of every description (some appalling and some, we thought at the time, groundbreaking); on weekend nights it burst at the seams with drunken students ready to cheer for, holler at, or, when the evening grew sufficiently old, projectile vomit at, said entertainment.

We’d arrived early enough to grab a table at the front (the place didn’t get really zoo-like till at least eleven o’clock) and were immediately subjected to an opening act. The house lights faded and the stage lights snapped on as a pair of performance artists, your typical male/female team of pseudo-thespians hailing from the nearby school of art, burst onto the stage — and when I say typical, I mean they were shaved bald, stringy-muscled, and the colour of dough, as if they’d spent time in the anti-gym, paying special attention to the reverse tanning bed. They spread industrial-sized lengths of clinging plastic wrap on the floor, stripped naked, and began rolling around on the sheets as the William Tell Overture blared over the PA system and they bellowed “LUNCHEON MEAT, LUNCHEON MEAT” in a monotone dirge.

And so they rolled, until the woman somehow became entangled in a non-art school way, and her buttocks, now truly bundled like a gigantic ham, hovered in front of our table. Beside her, the man finally lay still, stretched out on his back and wrapped up in an orderly fashion, like ... like luncheon meat, if we were to get the drift of their artistic statement (which I’m sure Audrey did, despite her comment of “that ain’t no Schneiders he’s got there”); but the woman continued to struggle mightily, inadvertently waggling her mound of shining, packaged flesh at the crowd. Katie, now hooting loud enough to rival the sound system, pointed at it with tears running down her cheeks. In rebuttal, the woman on stage glared back over her ass at our table.

At last two enormous men, clad in leather aprons smeared with red paint, bound into view from the wings (undoubtedly early, to save the woman further humiliation), each clutching a meat cleaver in one balled fist; in unison they stooped, and, with their free hands, scooped up the artists/pimento loaves and threw them over their shoulders in dramatic fashion. As they exited stage left, chanting,“ Hi ho, hi ho, it’s off to market we go,” the woman looked up and, casting a scathing look at Katie, mouthed the word asshole.

Perhaps Katie found the irony of the utterance the ultimate punchline, considering what the luncheon meat lady had exposed us to for the past minute, or maybe it was just the drugs talking, but her laughing jag continued as Television’s “Venus” started pumping through the speakers. Then a waiter drifted by, and we ordered our beer as a sound crew scurried out and began setting up onstage.

We talked now, raising our voices over the occasional “testing, testing” coming through the mic and the odd guitar riff jumping out of the speakers, until the beer arrived — four pitchers, sweaty and cold — not enough to cut the mushrooms, but a start, at least. As we poured ourselves glasses, Adam let us in on some household news.

“Oh, by the way. We’re getting a new tenant tomorrow,” he said.

We’d been one person short for a while. Cindy Crawford (not the supermodel) had left on a month-long trip to Greece some time back, and we’d just recently received a postcard, cryptic in nature but to the point. It read: Having fun, guys, and making money. Won’t be coming back, so rent my room.

“Man or woman?” Katie asked.

“You know the rule,” Adam replied, telling us her name. “She’s a friend of Cindy’s.”

“Good-looking or butt-ugly?” Audrey asked.

Adam gave her a why-do-you-even-ask look in response.

“Doesn’t matter,” Katie said.“ You won’t be getting into her pedal-pushers, either.”

Audrey let out a whoop and stuck her hand in the air for the big high five; Katie swiped, missing by a half a foot. The two corn-fed gals looked at each other for a beat, eyes wide with astonishment, then collapsed together in a laughdrenched hug. The mushrooms, the Thai stick, or the combination thereof had done absolutely nothing for their coordination, but the contraband had certainly cranked up their sense of humour .

I couldn’t help but laugh, too. There I sat, high on life, as brown and hard as a nut, with an ice-cold pitcher of beer in front of me. Sure, I had to work the next morning, but I existed in that brief window of time — long enough after high school to have rinsed its foul taste from my mouth, but not so long after that reality had forced itself upon me yet. I lived where no task too difficult, no weight too heavy, no thought too profound could get the better of me. Moronic man-child that I was, whatever flaws I owned I could easily ignore.

Then the band jumped on stage, a group I’d never heard of before — REM — and they broke into an extended version of “Stumble.” As a cultural moment, this may not have been CBGB’ s, 1976, with the Talking Heads on stage, or Woodstock ’69 with Hendrix setting his guitar on fire, but it felt good; I felt all right. I lit a smoke, dragged deeply, then tilted my glass to my lips. A jolt of electricity ran through me and wouldn’t stop; I eagerly awaited the arrival of the beautiful ... now, what had Adam said her name was again? That’s it. The beautiful Madeleine Moffatt.

I know Maddy does it, too (the giveaway for her is the distinct I’m-not-really-here look in her eyes), but sometimes when I’m sitting in the overstuffed chair wedged into the southwest corner of the living room, the chair set right by the cold-air return, I’ll place my newspaper or book in my lap, turn off the CD player, and furrow my brow in concentration. When I do that, I can’t help but overhear all conversation coming from the rec room in the basement: the boasts, the taunts, and the beautiful notions, too, that twelve- and thirteen-year-old children share amongst themselves.

I don’t think of it as deceitful; as a parent, you take what you can get without pressing your ear to a milk glass placed against a wall or hovering, breathless and statue-like, just outside a closed bedroom door for minutes at a time. If it’s in the air, it’s public domain.

Still, what am I hoping for when I sit there with my head cocked, with every fibre trained toward them, and try to intercept their unguarded thoughts? A whiff of their secret lives, drifting upward like a wisp of smoke? The secret lives that I’m sure exist but I’ve never been made party to, accidentally or otherwise?

Absolutely not. I have enough trouble handling my face-to-face interactions with Rachel and Eric and coping with the small, nagging doubts those moments leave — simple doubts like Geez, could that casual comment have been misconstrued as some kind of scarring put-down? and Should I step in with some advice now, or is this the time to stand back?

And when I compare my life at age twelve or thirteen to what Eric and Rachel are experiencing now, when I search for any kind of reference point to help in the intricate task of parenting, I just complicate matters. I’m peering back through a window frame that’s cracked and warped with the passage of time, and the pane of glass it holds is flawed, caked with dirt; I’m imposing values that were applicable to a different generation — or, worse still, I’m imposing values that I never bothered with myself. I find the thought of either of them putting a cigarette to their lips unfathomable.

Of course I’m a hypocrite, employing reverse what’s-good-for-the-goose-is-good-for-the-gander ideology at every turn. Maddy’s far better at being fair, at articulating the voice of reason, of just knowing what’s right, for Christ’s sake. When our term is up and Eric and Rachel have blossomed into adults straight and true, Maddy’s contribution will have made all the difference. Still, I have to admit, I have been donating my particular share.

Case in point: not that long ago, I took Eric to a National Sport (the big one up on Durham Mills that caters mostly to country club members and their young heirs) to replace the baseball glove he’d left on the park bleachers a few weeks earlier. The summer’s first heat wave triggered this action; after more than a week of everyone staying close to home and the central air whenever possible, it dawned on Maddy and me that we were in danger of becoming a household of recluses.

It came to us as a family (the adult portion, at least), as we sat huddled in the basement, sipping iced colas and watching Killers from Space, one of those god-awful horror movies from the fifties, on the Scream Channel (#148 on the infinite dial — no, make that the Möbius strip, which is worse than infinite) one Saturday afternoon.

During a commercial, Maddy scanned the curtain-dimmed room, her gaze stopping on the two youngsters sitting cross-legged on the broadloom directly in front of the TV.

“Can anyone here tell me,” she asked, pausing dramatically, “what is wrong with this picture?”

I knew where she was headed so I kept my mouth shut; quite possibly, Eric and Rachel knew, too, although it’s hard to say for sure.

“Well, the special effects are poor,” Eric said, straight-faced. “The acting’s a bit wooden ... and the least they could have done is colourize it.”

Maddy, too, might have sensed that she was being played with — just a bit. A smile tugged at the corners of her mouth.

“Nooooo,” she said.“ That’s not exactly what I meant.”

“Oh, oh, I know,” Rachel said, thrusting her hand in the air with the urgency of a brown-noser.“ We’re all sitting around the basement like a bunch of mushrooms when we should be out enjoying this scorching summer day.”

“Bingo,” Maddy said.“ I couldn’t have put it better myself.” Rachel eyed her suspiciously. “I said scorching. That’s sarcasm, Mom.”

“I’m fully aware of that,” Maddy said. “I think what your mother’s trying to say,” I said,“ is that you can’t let a little thing like weather keep you in the house. When I was a kid, I’d be out playing football or baseball or whatever all day, even in a heat wave like this. I’d crawl home for supper drenched in sweat.”

“There weren’t any heat waves when you were a kid,” Eric said.“ You were born during the last ice age.”

“That’s Cold War, baby boy, and you’re not the least bit funny,” I said. “But we’ve all been through this before, so we’re not going to go through it again. You two decide what you’re going to do.”

What we’d been through was this: Eric and Rachel, though merely middle-class, suffered from an embarrassment of entertainment riches — endlessly redundant television, video games, computers that linked them to the entire world, and much, much more — and were capable of staying indoors and not seeing friends for three or four days at a time. Their friends, similarly equipped, often fell into the same trap. And the parents, selfish, stupid, lazy, or just filled with misguided love (okay, we never belaboured these points), indulged their children in this behaveiour. On the odd occasion, a boy or girl not ours might wander by, slouched and wan, and utter a “Hey, Mr. Kearns” or a “How ya doin’, Miz Moffatt?” before stepping through the doorway to the basement; undoubtedly banished from a foreign residence for the crime of over-familiarity, the interloper would then descend into the void with a cache of video games or DVDs clenched in his or her fists.

Heat, rain, soothing temperate breezes, none of these factors influenced this pattern; kids, at least ours and the ones we knew, lived this way during the summer (or any time, actually, when free of school for a decent stretch).What severe weather tended to do was coop families together for extended periods of time during non-business hours and draw attention to this problem.

So Maddy and I issued our worn but simple edict: step outside. It was that basic. Sports, a walk, even something as passive as standing beside a tree and taking in the air would fit the bill.

After Killers from Space and by a third of the way through The Man with the X-Ray Eyes,we’d winnowed it down to this: Rachel, cellphone in hand, would trek the three blocks to Chantal Watson’s house without calling in advance, guaranteeing herself a walk. If Chantal was home, Rachel would call to let us know she was staying. If not, she’d come home and help Maddy in the garden.

Eric, slyer still, had opted for the baseball glove purchase. Not baseball itself, or at least a game of long toss or five hundred with me over at the park (using Rachel’s glove for the afternoon), but driving up to National Sport and picking up Slurpees on the way home. This, of course, was one of Eric’s famous back-end deals. Not much in the way of outdoor activity now, but the promise of substantial frolicking in the sun later: “A whole summer’s worth, for cryin’ out loud! Starting tomorrow!”

So we drove north, away from midtown traffic, up to National Sport and its fashionable-suburb prices. But we’d dallied till late afternoon, allowing the heat to climb from uncomfortable to punishing, and Eric’s face, shiny and red to start with, now beaded over at the forehead and lip as we travelled.

For an instant, I felt sorry for him.After all, late last fall, in a fit of thrift, Maddy and I replaced our aging auto with a newer aging auto, laying down five thousand cash (but taking on no monthlies) for a ’99 Mustang. Mechanically sound, rust-free, and with minimal mileage on it, the car held two major flaws: racing stripes (which we knew about) and no Freon in the air-conditioning unit. It blew, all right — just not cold.

Yes, poor Eric. But bad-taste Biafran jokes aside, I’d heard somewhere recently, in a World Vision commercial, I think, that twenty-seven thousand children die daily throughout the world from malnutrition and disease. Twenty-seven thousand. Daily. The sound byte had stuck, popping into my conscience on occasion and diluting at least some of the empathy I might have for a daughter whose jeans just weren’t faded enough, gosh darn it — could we run them through the washer again? And a son who, although quite sweaty, was on his way to buy an apparently disposable ninety-dollar baseball glove and an iced sugar drink verging on poisonous. He could roll down his window to cool off.

He had, of course, as had I, and we now bombed up Pleasantview Boulevard with the wind tousling our hair and the stereo rumbling. Mixed tapes filled the car’s glove compartment: Maddy/Rachel mixes, Maddy/Jim mixes, Rachel/ ... actually, every combination possible except for Eric/Rachel mixes because neither of them drove by themselves. Sometimes we’d spend a Friday or Saturday night laughing, razzing, and gnashing our teeth as we chose cuts for the next car tape, goading each other into more personal and vexing choices as Cat Stevens followed The Stranglers who followed Pere Ubu who followed Nelly, all the while kicking each other’s butts at blackjack or three-card draw; and other times, we’d behave with a social conscience, trying to satisfy all tastes concerned as we played a civilized game of Scrabble or Trivial Pursuit.

But right now, as Eric and I cruised the boulevard, we listened to an Eric/Jim mix, a father/son showdown, a no-holds-barred goad-a-thon, the speakers vibrating as we crested Pleasantview’s long rise and turned onto Durham Mills.

The next tune up was by Pale Prince, the music industry’s latest attempt to loosen Eminem’s stranglehold on the trillion-dollar angry-white-suburban-teenager rap market. “Pale America” I think the rhyme was called, and it opened with a sonic blast:

Open yo’ eyes, The Man is whack, Been thirty fuckin’ years since he knew what’s mack. See him smoking’ his ceegar in his Lincoln Continental, He’ll tell ya what to do ’cause he’s mutha’-fuckin’ mental. So listen up good, listen up Jack, If you fuck wit’ me, I’m gonna fuck you back.

I glanced at Eric, who purposely looked straight ahead, nodding in time with the beat. This song was one of his knockout punches on the tape, a statement, but Maddy and I had already discussed it in private, again coming to the conclusion that sometimes the message wasn’t as important as the messenger. This pale guy was The Who forty years later, except surlier and with a fouler mouth, but that’s inflation for you. I’d gone the same route. Eric was smart enough to take any clever things from his songs without embracing the notso-clever (although we were aware that other parents had made the same general assumption only to find it faulty).And then, of course, there was this: banning a popular form of music from a thirteen-year-old boy wasn’t just Amish in nature, it was like lighting a one-inch fuse on a hundred-pound-plus keg of dynamite.

We continued along Durham, which grew into a busy three-lane thoroughfare running east-west through the north of the city; around us, streams of cars jockeyed for position, closing up openings in the blink of an eye. I looked below us to south, to midtown, downtown, and the lake beyond. A vast, dirty yellow cloud hung over everything, a duvet of crap smothering the top of any building over sixty storeys tall. It stretched west for forty miles, where you could watch it meld with the vapours oozing from Hamilton’s steel mills.

The city hadn’t been this way when I moved here twenty ... twenty-what? twenty-four years ago.The population seemed to be growing exponentially, here, there, everywhere, spreading, hugging the waterways and rivers, befouling them in the same way fatty yellow chunks of cholesterol choked arteries.And now the heat pinned down our collective stink; I could smell it blowing through the car.

I looked back at Eric; he continued nodding, looking straight ahead. And, as sometimes happens when I look at him or Rachel for too long, I was struck by this recurring thought: the number of ideas they hold in their handsome heads don’t nearly add up to the amount they share with Maddy and me. Of course I know my children well, but only as much as they’ll let me. So I asked: “Hey, Eric. Are you happy right now?”

He looked at me quizzically.“Huh? You mean right now?”

“Well, yeah, right now. But in general ... with life, I mean?”

“Uh-huh, it’s pretty cool,” he said, still nodding.

Always quick with a quip or a comeback in response to day-to-day things, Eric often turned reticent when challenged with those deeper questions — like “How’s life?” and “Are you happy?”Their answers scared him, I think, now that his life was becoming so much more complicated than Winnie the Pooh videos and who got the most pudding for dessert, but who was I to help supply the real answers?

So there we sat, side by side and on our way to the sporting goods store, both two-thirds full of testosterone, him filling up with the stuff as he aged and grew, and me pissing it out as I aged and shrank. Hormone flow and rational thought never mixed well to begin with, and our positions, me searching for footing as I slipped down the north side of the slope and him struggling past obstacles as he started up the south side, made it that much more difficult.All of those steps he now approached, first girlfriends, sex, fitting in, were difficult enough without some fragile, finger-wagging know-it-all looming over him with outdated tips and a list of rules. Of course Pale Prince made sense to him. Who else to help with the fear and anger? But where was my knight in shining armour to help me understand and accept that although once a week may seem vexin’/you couldn’t fuckin’ stand much more sexin’ and issues much more important than that?

I had no Pale Prince, but as he faded out and Neil Young’s nasal voice leapt through the speakers, I started to feel better again. Not that I considered him a spokesman for my generation or a great reliever of my particular stress; I just liked his music — and, almost as importantly, Eric didn’t. I grinned, anticipating his response.

“Oh no, not this guy!” he said, as “For the Turnstiles” wafted through the air.

“The Godfather of Grunge,” I said, grinning wider.“A rock and roll icon.”

“He can’t sing,” Eric said.

“You’re missing the point,” I said. “It’s not about clarity of voice, it’s about clarity of style, the combination of persona, talent, meaning. It’s the package.Your doofus is no different.”

“No way. Rapping’s not singing.”

“That’s for sure,” I said.

We could have kept bickering, but we’d come to National Sport’s parking lot. I signalled and wheeled in, immediately falling into cruise mode as I looked for an empty space.The lot hugged the west side of the store, and I followed its one-way arrow, painted onto the pavement, past the single row of cars parked on each side of us. I could see that the lot blossomed to full size at the rear of the building, but here it was just the two rows, one on either side.

Halfway down the strip, I noticed an empty spot and drove towards it, signalling, assuming it was ours. But even as I made this assumption, a Lexus SUV, waxed and polished and glowing like a comet, swerved around from the back of the store; ignoring all arrows, it streaked toward our space, trying to make up twice the distance in half the time.

Eric and I stared, dumbfounded, as a young couple, beer-commercial extras bedecked in dazzling tennis whites, hurled their van toward the open spot in front of us. I punched the car forward and cranked the steering wheel hard right.We hit the brakes simultaneously, coming to lurching halts with a yip of spent rubber and a kiss of bumpers. I thrust my head out of my open window.

“What the fuck are you doing, jerk? It’s a one-way!”

He reached for his door handle, and my heart, already hammering, picked up its pace. This was it, I was sure. I was seconds from rolling around in a parking lot, kneeing, punching, pounding, with Eric looking on in terror. I felt my scrotum tighten.

But before the other driver could open the door, his girlfriend flung out her hand and grabbed his shoulder; I could see her fingers dig into the flesh beneath his shirt.

They talked, both anonymously and animatedly, in their climate-controlled cab as I waited with my head still thrust out my window and a tough-guy sneer masking my mounting fear. They kept arguing, with the man — no, the boy, really — occasionally jabbing a finger in my direction.Twenty at best, whip-pet lean, with corded forearms and a head of curly black hair, he looked like a pro tennis player — or at this point, with neck veins popping and spittle flying, a pro tennis player wanting to punch the shit out of a line judge.

Who knows what they talked about. Maybe the woman swayed him with reason, pointing out that, yes indeed, they did speed the wrong way down a one-way parking aisle to try to steal this spot from us, and they’d best move on. Or maybe her part went something like this: Don’t do it, Chad! My high-powered lawyer/father couldn’t possibly finagle you out of a third straight assault charge! And who knows, you might kill the old fart!

But whatever she said, he agreed to it, throwing the Lexus into reverse. Then, as he lurched forward and sped past our car (continuing in the wrong direction) he somehow managed to mime, with passable accuracy, that I fellate him. For a fleeting second rage flew over me, equalling my fear, and I wanted to back up and ram him. But just as quickly it passed and I rolled into the parking spot.

I sat motionless for a moment, gripping the steering wheel with both hands, my elbows still locked, before I finally blew out a huge breath.“I need a smoke before we go in,” I said, cutting the engine and opening my door.

Eric and I met at the trunk; both of us propped our butts against it and I lit my cigarette, taking in that first big, greedy drag, getting some nicotine to my brain. I watched the smoke leave my mouth in staccato puffs as I turned to him and spoke: “Do you remember that trip to the grocery store a couple of months ago?” I asked.“The one where your mom got all PO’d?”

“The day she walked right into the house and left all of the bags for us? You bet.”

Discounting the occasional well-deserved blowout, the odd raised voice or cold shoulder was memorable anger for Maddy. That scene had stuck with the both of us.

“Well, I’ve thought about it a lot,” I said.“Especially what she said when we were in the car. Do you remember any of that?”

He looked up at me. “Uh, which part?” he asked. “The bit about not everyone in the world being an asshole, and how you shouldn’t teach your children that they are?”

I smiled.“That’s the bit ... more or less.And she had a point.” Not only did she have a point, she’d reminded me of it since. But even now, as my nerves settled and the danger seemed to have passed, I wanted to overrule her; I wanted to go on a rant and tell Eric that the world brimmed with fucking morons just like that guy in the Lexus and what he truly needed was not forgiveness or rational conversation but a couple of shots to the teeth. Of course that’s what I wanted. But I knew better, and I knew if Maddy were here, she’d want me to extend myself, to find higher ground. So I took another drag and started talking, looking for the words as I went along.

“Your mother’s absolutely right. I can’t always be imparting those kinds of ... values. It’s a big world, with lots of good in it — if you show some patience and don’t make assumptions. I guess what I’m saying is, not everyone out there is an asshole.”

Eric continued looking up, his eyes wide. Probably still scared (I know I was), wired from his brush with violence, his aura seemed receptive; at this point I felt as though I were in the middle of one of those father/son moments, a moment when I should pass on something long-lasting, something of value. A truly valid point. But what?

“It’s probably more like a seventy-five/twenty-five split,” I said at last. “With twenty-five percent being decent, thoughtful human beings most of the time.”

Still leaning, his arms crossed, and his lower lip thrust out slightly, Eric remained motionless for a beat, imagining what? His classroom? The schoolyard? Friends? Bullies? People and places I knew nothing about? Finally he nodded. “Yeah, that’s about right, I’d guess.”

Just at that moment, a woman approached. Probably in her early thirties, she favoured the big look, sporting oversized sunglasses, huge hoop earrings, and large, shiny hair; no deus ex machina placed here to supply a punchline to our small talk, she lugged a National Sport bag, undoubtedly filled with boxercize and jazzercize apparel. In her other hand she gripped both a cellphone and an unopened pack of Kools. She pressed both to her ear.

“That’s right. Mr. Limpdick’s three days late with the child support already.” She paused for a moment, then: “You bet I’ve phoned my attorney ... can you hold for a second, Becky?”

She took her phone and cigarettes from her ear as she passed us and began struggling with the pack’s cellophane wrapper, helping her cause with an emphatic “Son of a fuckin’ bitch.” Well past us now, she finally managed to rip off the wrapper, and the scrap of plastic fell in her wake, caught the breeze, and scuttled across the pavement in our direction.

I turned to Eric. His eyes were riveted to the Louis Vuitton jeans papered to her hips, and he kept staring as nature’s perfect billboard shifted and swayed into the distance. He didn’t even look down when her cigarette wrapper caught the tip of his running shoe, stuck, and fluttered, pinned by the wind; and there we stood for a moment, in our own little microcosm.

Seventy-five/twenty-five? I’d been generous. No. I’d lied. My true feelings on the subject were this: ninety percent of the people walking the face of this planet were capable of truly stupid behaviour and much worse, whether dishing it out, receiving it, or having it tied onto them like straightjackets. Iraq, Rwanda, Mogadishu, Croatia, Ireland, the projects in any North American city, Muslim women, Native people, the caste system in India, the treatment of gays, wife abuse; I could go on and on about human behaviour in any segment of any society at any time. Even as scientists crack the genetic code, slaughter, oppression, and bigotry remain commonplace, and it seems unlikely, even with all our marvellous technological advances, that the identification and eradication of the asshole gene will ever occur.Three thousand years from now when humans attired in flowing robes and bearing expanded craniums à la Star Trek roam this earth, they won’t be bent on discovering a theorem for peace, love, and understanding.Their huge heads will be busy inventing better weapons — and at closer quarters will be much better targets for each other’s puny fists.

But hey, for the sake of Eric’s development as a human being, I was willing to concede seventy-five/twenty-five. And I assumed that Maddy would congratulate me for my flexibility if word of it ever got back to her. Go figure.

Regardless of life’s complications, of stubbornness gained and flexibility lost, I knew from the start that I’d love Maddy forever.

I understood this the day she moved into Adam’s house. I’d just finished an eleven-hour shift, a shift so hot and exhausting that by well before morning break it had wrung the Vince-induced hangover from me like foul water from an old, wet sock. And now, aching, streaked with sweat and crushed rock, and with the steel caps of my work boots broiling my toes, I limped into the house and poked my head through the kitchen doorway — just to catch a glimpse of the owner of the new, lilting voice coming from within before I took my shower and collapsed into bed.

Of course, the siren’s song was hers. She sat across the kitchen table from Katie; a glass of white wine sat in front of each of them and a single enormous suitcase rested by Maddy’s side. I’d never seen a woman like her before — a woman who could look so incredible with no apparent effort. She glanced at me, with her auburn hair, straight and clean, falling over the shoulders of her plain white T-shirt and touching the waistband of her faded Levis. Her flawless skin, with no hint of makeup, and her face, with its perfect symmetry, mesmerized me instantly. Beauty without fanfare: was she even aware of it?

Looking back, I realize I was seeing everything through a burst floodgate of hormones; I think Katie had picked up on this, or, more likely, anticipated it. She laughed loud and said, “You’re pathetic, Jimmy boy. No, check that — you’re just a man and all men are pathetic.”

“What are you talking about?” I said.

“Look at you. Flexing in the doorway for the new broad.” She turned and looked to Maddy. “No offence, Maddy. Just making a point.”

“None taken,” Maddy replied, smiling, making herself even more beautiful.

I took stock, and yes indeed, there I stood, in my strap T-shirt, both hands up, not so nonchalantly gripping each side of the door frame as I peered into the kitchen. Perhaps I should have called out “Stella!” But really, it wasn’t my fault.The fabricated stance, honed and evolved over the millennia, genetically encoded, stated that I could, in fact, offer protection from the saber-tooth and the mammoth. And in my defence, my body was new, improved, and although still not in the babe-magnet category, held fifty percent more attracting power than I was used to wielding. If I’d struck a pose like that six months earlier, I’d have been laughed out of the room.

But I’d been unmasked now, so I dropped my arms. “Well, don’t just stand there looking bug-eyed,” Katie said. “Come on in.There’s beer in the fridge.”

Our kitchen at that house was vast, the floor a sea of twoby-six planks painted navy grey, uncluttered except for a yellow and black scarred Formica table surrounded by a ring of rickety, non-matching wooden chairs.A fridge and stove set, circa 1963, completed the decor, but we didn’t use either very much. Mostly, we used the fridge for a cooler, the coffee-maker for nourishment, and the table as a meeting place.

I opened the fridge door. A six-pack of Amstel Light sat chilling along with the wine. I’d noticed, too, that the women had been eating what looked like endive salads, courtesy of La Petit Gourmet, a pretentious takeout place around the corner.A normal Saturday night meant pizza, wings, or Chinese food, with a minimum of twenty-four beers sitting in the fridge. Things just didn’t add up. But confused, and more than a little nervous in Maddy’s presence, I held my tongue.

“So anyhow,” Katie said, “Madeleine Moffatt — or Maddy, as she likes to be called — meet Jim Kearns and vice versa.”

I nodded from the fridge.“Hi, Maddy,” escaped my dry lips like a croak.

She smiled and said hello back.

Then Katie said,“Y’know what? Despite Jimmy here being a total goof, I think you guys are going to really get along.” I don’t know if you could call it shameless, but obviously she was instigating something.

I walked to the counter drawer, looking straight ahead, and started sifting through it for a bottle opener. I could feel the back of my neck flushing. I liked Katie a lot, and she liked me, too, but I’d always felt we’d existed under the unspoken decree that we shouldn’t act on our feelings — that two people of our nature coming together would be like mixing matter and anti-matter, a fart and a flame, that the union would be glorious but brief, ending in some kind of explosion and ruining everything. Plus, she intimidated me. She’d broken up with her last boyfriend (a greasy womanizer, it turns out) via the telephone. With the entire household sitting around the living room listening, she delivered this parting shot: “Here’s your problem, jerkoff.You think your penis is big when, in fact, just its aroma is.” She paused for a beat, listening, barked out a laugh, then continued.“You make me want to puke. Don’t ever come near me again.” And he hadn’t, leaving half his wardrobe and an entire record collection in her possession. She’d kept the records and donated the clothing to the Salvation Army, apologizing to a puzzled-looking clerk for her momentary lack of taste as she placed the stuffed-to-bursting duffel bag (also the ex’s) on the counter.

But as I said, we liked each other, did things for each other, and as I look back on that day now, in search of the highs and lows and rights and wrongs, I do find that pretty amazing.You would never see a cougar or rhino pitching a friend’s virtues during mating season; it would be all snarls and head-butts. Of course it’s normally that way with humans, too, during the mating years, at bars, parties, wherever, but those moments exist that separate us from the lower animals. And here was one now, as Katie, obviously calling the shots, tried to present me as civilized, intelligent, even nice.

I turned with my open beer and sat at the table, close enough to catch Maddy’s scent for the first time. Her scent.How’s that for romantic bullshit? But it’s true, too. She smelled clean and pretty (words I normally wouldn’t assign to a smell), and beneath that, I guess, pheromones floated, plying a subtle magic that men and women can never consciously wield.

I spent my first minutes at the table — if it’s possible to remember being in a daze — just looking at my right hand wrapped around my beer, watching the ingrained grime in the crook of my thumb turn slick from the bottle’s sweat as I listened to them talk and laugh; and then Katie struck again, guiding the conversation to common ground.

“So, anyway, Maddy,” she said. “You mentioned earlier that you’d studied P.G. Wodehouse in one of your courses last year. Jim’s a huge P.G. fan.”

“Really,” Maddy said, turning to me.“That seems like a rarity these days.”

I believe I responded in the affirmative, with something like: “Oh yeah, uh-huh.”

Luckily, Maddy, trooper that she is, kept going.“I ran across him at the end of Grade 9. I don’t think I stepped outside a single day that summer — except to go to the library and back.”

That was it.Together, they’d tossed me some sort of mental lifesaver as I’d floundered in my choppy sea of nerves and exhilaration. I took a huge swallow of beer. “It was Grade 11 for me,” I said, my brain and tongue finally starting to mesh like gear and cog. “I read every book in the Jeeves/Bertie series, including the short stories, during Christmas break.”

“Well take my advice and never sign up for a course called Twentieth-Century English Masters,” Maddy said, shaking her head.“Having to listen to theories about the Drones Club representing the downfall of the British Empire came close to ruining it all for me.”

Not an auspicious start, I know, but short of pulling someone from a flaming car wreck, what is? And relationships do have to start somewhere.

We talked through dusk and into the night, the words coming easier and easier for me; throughout the rest of the house, people came and went, introducing themselves to Maddy as they passed through the kitchen. On occasion the stereo would rumble to life from the living room, spewing out Lou Reed or the Stones, and still we sat, perched on our small, hard chairs. By ten, a small party had broken out, and the smell of weed drifted into the kitchen. By eleven, the party and the smell of weed had drifted off, to the Vince or another house, as did Katie, winking at me as she backed out the kitchen door, and still Maddy and I talked.

By one o’clock, as I pulled off my boots and peeled away my work clothes in preparation for my shower, my thoughts were a total jumble. Maddy was by no means mine; serious courting and planning lay ahead. But at that particular time, it didn’t matter. Nothing mattered, really. All at once was I, several stories high.There weren’t no mountain high enough, there weren’t no ocean deep enough ... all of that crap crowded my head, if not the songs themselves, their imagery and feeling, from the most perceptive right down to the corniest.

Maybe, when it’s all said and done, that’s partially what rankles now. Those initial months of true love, when you stagger around in a delicious fog, perhaps comparable only to that instant you first hold your newborn to your heart and know you’d die for him — when do you acknowledge that you’ll never reach those heights again?

And once you have acknowledged that, what’s left to do but mark time?

I like to mark time, or a small part of it anyway, by hitting the heavy bag. I hung one in the garage the year Rachel turned seven, the year ... well, never mind that for now. I put it up five years ago, screwing a heavy-duty eye hook into a crossbeam, clearing all unnecessary items to the side, and setting a boom box at low volume on some raucous radio station twenty-four hours a day to keep the raccoons away. Once they set up shop in a place, they wreak havoc and the stench is unbearable, but the radio’s presence makes them think the garage is constantly occupied.

Punching the bag has been my tai chi, my yoga.When I let my hands go, I feel all tension and negative thoughts go with them. I transfer everything into that swinging, sixty-pound sack; it must be pure evil by now, a black hole of bad karma, with its true weight approaching immeasurable, because, let’s face it, mad, bad, and sad weigh a fuck of a lot more than glad. These are things you notice in your step, in every movement, in fact, when you have to carry them around year after year.

So three times a week I slip out the back door with my hands taped, from my knuckles up to just past my wrists, and with a pair of sparring gloves slipped over the wraps. I probably should wear twelve-ounce gloves to prevent knuckle separation, but then I’d lose what little feeling of speed I enjoy. Besides, my hands are already screwed from decades of gripping shovels and clutching paving stones, the tendons and ligaments stretched to their limits under the constant parade of loaded wheelbarrows.