Читать книгу Dig - David Nichols S. - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

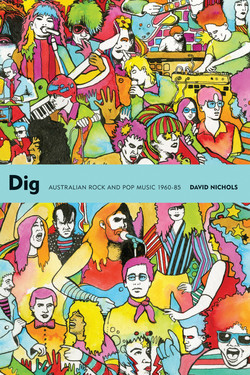

Оглавление5 The Snap and Crackle of Pop

THE MID TO LATE SIXTIES

‘There’s a new age dawning this year, he told me. ‘An old cycle’s ending and a new one begins, in 1966. Did you know that, Dick? The earth-forces will come into their own, and people will be liberated.’

– C. J. Koch, The Doubleman1

The story of the counterculture that developed in the western world in the late 60s is, like that of any mythological era, riddled with half-truths crossed with untruths. As we shall see, the notion often expressed at this time that all was now opportunity and possibility – from the breaking down of rigid, millennia-old institutions to the radical act of releasing a single that was more than three minutes long – amounted in fact to one step forward, three steps in another direction entirely.

Visceral and showy, it is easy to imagine the period as boldly painted in illusory deep patterns of ultra-sensation. ‘Somehow with the optimism of the sixties,’ the film director Peter Weir claimed two decades later, ‘there was a feeling that everything was going to work out, that you didn’t need to plan.’2 Of course, this is only a very small segment of the cultural mix, inseparable from the rest. Pip Proud claimed that the best way to typify the late 60s in Sydney was as a time when special inspectors had the power to measure women’s bathing costumes at Sydney beaches – which is to say that it was a time of prudery thrown into stronger contrast by a small number of ‘liberated’ minds. Certainly the Australian government remained conservative throughout this period, during which three Prime Ministers – Menzies, Holt and the slightly more interesting Gorton – presided over a persistently strong ‘lucky country’ economy.

Similarly, even though the counterculture was sold by means of rhetoric that invoked anti-commercial, even anti-capitalist values, a general cynicism prevailed in many quarters as to whether particularly ‘out there’ artists were genuine and their work valid, or if consumers were not so much going on a trip as being taken for a ride. This scepticism extended even into the alternative scene(s). Essentially, there were very few people throughout the world, including Australia, who didn’t think that the action – where the beautiful people were making free decisions based purely on their own enlightenment – was happening somewhere else. Barry Miles, a self-proclaimed insider in the London ‘underground’, has discussed the way his small, select gang felt that the Move, a group from Birmingham, had demonstrated hypocrisy by suddenly experiencing an ‘overnight conversion to hippiedom’ when they released ‘I Can Hear the Grass Grow’ in early 1967. ‘The point,’ says Miles, ‘is that psychedelic music grew from an environment, a very specific London one . . .’3

In fact there are quite a few ‘points’, and the most pertinent one is that while many, indeed most, kowtowed to London as the centre of the counterculture universe during this time, there is no reason to assume that London’s psychedelic explosion was any more exciting than anyone else’s. Miles is presumably speaking only from his own experience at what seemed like the pumping heart of a movement. For that matter, when Proud ventured to London at the very end of that decade he found that his few Sydney friends who’d made good didn’t want to know him, and the scene, in general terms, was dismal. In any case it is quite possible that the interpretations of that cultural style that were created in other places were more impressive than the original – whatever that original actually was. Russell Morris’s ‘The Real Thing’ may be ‘a dog of a song’ without ‘much there melody-wise and lyric-wise’, as Dave Mason of the Reels once put it.4 But as a studio experiment allowed to run riot in the form of a 7” single, it was a stunning leap in a new direction, and its similarly chart-topping follow-up, ‘Part Three: Into Paper Walls)’, went twice as far again.

Many others talk of this period as one in which technology (especially those mundane matters of amplification and multi-track recording) could never match their own vision or ambition; at the same time, tape recording was becoming more convenient and compact: a ‘new boom in electronics’ was announced in 1967, as the cassette tape was readied for launch.5 Similar advances at both the home and public music production level were made rapidly in the later 60s and into the 70s.

Very few people of any stripe trust art, or their responses to it, and art – pop music included – often goes out of its way to be untrustworthy. Towards the end of Patrick White’s 1970 novel The Vivisector, a life of the fictional modern artist Hurtle Duffield, White gives over more than five pages to snatches of dialogue from the vain, trivial, pretentious and foolish glitterati of Sydney responding (or not) to a retrospective of the artist’s work. The themes of the babble include whether or not Duffield sells largely to Americans, how rich he must be, and how little the attendees actually understand the work in question. It’s an extended riff on the same type of hollow chatter Jan Smith relates from the Beatles press conference (see chapter 2). White, as one of Australia’s most celebrated and yet most misunderstood writers, is in part bemoaning his own fate (he even includes a dig at himself6), but he is also reflecting on the fate of creators in the marketplace, as indeed his character’s life itself is an extended reflection on the 20th century in Australian art. The point White makes, writing as he is on the cusp of what would turn out to be non-indigenous Australia’s greatest leap to date in terms of artistic flowering, is that art and commerce are inseparable, that commerce’s blunt, mulish desire leads art wherever it wants it to go. Even in the case of Duffield – who comes (through adoption) from a wealthy background but whose interest in money goes no further than its power to free him to paint pictures when he pleases – materialism, the dictates of fashion, and the petty lives of the miserable rich women he courts are bound up with his life as an artist.

In 1970 Marty Rhone – a Dutch-Indonesian Australian with handsome, apparently Asian features and a string of very fine, but for the most part commercially unsuccessful singles behind him – released a self-penned parody song, ‘So You Want To Be a Pop Singer’. In it, he mimicked and satirised three vocalists who are rarely, for all their good qualities, spoken of in the same sentence: Russell Morris, Bob Dylan and Johnny Farnham. Rhone’s record focused particularly on the ‘manager’ operating the star (Ian Meldrum, Morris’s manager and Farnham’s manager Daryl Sambell were both referred to by their nicknames, ‘Molly’ and ‘Sadie’). Rhone was holding the pushy hand of the industry up for examination, and while he delivered the song with a smile on his face, its humour bordered on viciousness.

Rhone was vicious because the pop scene was tough, particularly for Australian artists. Only a small percentage of consumers would have failed to make a distinction between locally made and international records and acts. Increasingly, fans of Australian musical stars came to see international acceptance as, if not the raison d’etre of local performers, then certainly something worth grabbing at any opportunity. Record companies were, of course, complicit in this. Australia could be a proving ground for numerous artists, just as the Bee Gees or the Easybeats had honed their skills there. By the 1980s, groups like INXS were readily peddling the nonsense that their hardiness as a band was forged in the fabled ‘beer barns’ of the Australian suburbs. Yet it was also true that any Australian group which had experienced success in its homeland potentially offered the best of both worlds to a British or American record company – it was both new (at least to audiences outside Australia) and polished. Thus Bee Gees’ 1st, or Procession’s remarkably assured, crafted, and tasteful second take at a debut LP; or the Masters Apprentices’ third album, Choice Cuts, their first release in Britain after numerous Australian hits. The La De Das, the Twilights, Johnny Young, the Easybeats, Olivia Newton-John, MPD Ltd and many others were able to reinvent themselves in the northern hemisphere. But while Australian impresario Robert Stigwood’s willingness to take on an Australian group called the Bee Gees made it possible for them to land on their feet overseas, most Australian acts suffered as a result of the insularity and provincial nature of the ‘scenes’ they were trying to break into. This may well have been a result of outright prejudice in some cases, but more often – as we shall see – the networks that mattered simply weren’t available to new arrivals.

The internationalists nevertheless made inroads – although this in no way diminishes the worth and importance of those who stayed behind, many of whom were making even better records than their peers who’d been drafted to the UK by dint of having achieved everything they were supposed to achieve in Australia. The Australian-in-Europe professionals were often producing bland work in order to compete in the mainstream, whereas their former colleagues were relegated to the margins, where the greatest art is usually found. By definition, those at the margins usually don’t have the wherewithal to leave a very visible legacy; as a result, the official histories are riddled with gaps. Thus, for example, we have the account offered in the 90s by British rock journalist Martin Huxley, who dismisses Australian music of the 60s apparently because of its lack of international commercial success:

Such Melbourne-based acts as the Loved Ones, the Groop, Ronnie Burns, Normie Rowe and Bobby and Laurie, along with Adelaide transplants the Masters Apprentices and the Twilights (not to mention Bon’s old Perth pal Johnny Young) would never really figure out how to process their influences into anything authentic or personal and would never really produce music of sufficient merit to cause any sleepless nights for their overseas contemporaries.7

Huxley is attempting here to create a context for AC/DC, the subject of his biography, and (as non-Australian writers of books about Nick Cave have also discovered) it is easy to talk up your subject by deriding their contemporaries or context on the basis of their supposed obscurity. It’s even easier when you have evidently done no research. Huxley’s central premise, that groups like the Loved Ones or the Twilights were in the business of ‘process[ing] influences’, along with his assumption that the only success is commercial success, is ludicrous and beneath contempt. Try to imagine Pete Townshend in 1967 feeling nervous upon discovering that the Loved Ones, based in Melbourne, are a truly superb rock band.

When it comes to processing ‘influences’, journalist/social commentator Craig McGregor offers a more accurate picture of young Australians in the mid 60s:

The process of borrowing from overseas can be quite random. Duffle coats, winkle-picker shoes, drain-pipes, Beatle hairstyles and black stockings betray the English influence; whitewall tyres, Bermuda shorts, swept-back motorcycle handlebars, surf shirts and sneakers betray the American. But often there is an astute selectivity at work. Young Australians seem to have rejected the sentimentality of many US films and TV shows, but have accepted the American talent for self-criticism; it seems to fit in well with the sardonic tradition of local humour.8

OUTSIDERS AND INSIDERS

At least since the 1960s, New Zealanders have seen Australia as the next step up the ladder; a few have made the next step, beyond their greater neighbour (greater, at least, in size) and into the wider world’s consciousness. Max Merritt, for instance, was a figure to reckon with in Australia in the 70s, and his various incarnations of Max Merritt and the Meteors were famously inspirational to Australians who saw them play live.

This section introduces two important individuals who travelled from New Zealand to Australia in the mid 60s with their respective bands. Mike Rudd and Brian Peacock would both go on to play important roles as songwriters – and in other areas of the music industry – in Australia. Their stories are of great interest in themselves within the context of Australian music, and each of them, in a different way, also provides an invaluable take on the Australian scene from 1966 onwards. One significant difference between them concerns their outlook and approach: Peacock, who played in and wrote for the Librettos, Normie Rowe’s Playboys, and Procession, saw his time in Sydney, and later Melbourne, as an interlude; he was always en route to London. Rudd, who was a member of the Party Machine, then formed Spectrum and was simultaneously in Ross Wilson’s Sons of the Vegetal Mother, had rather different ambitions, and fitted into the Melbourne scene very early in his career. One important element in both men’s stories is Melbourne-born Ross Wilson, another remarkable and multi-faceted figure who will also appear at many points throughout this story.

Like so many of the strands in this history, beginnings, ends and definitive intersections can be hard to pinpoint. A motley assortment of private schoolboys in Melbourne’s bayside suburbs of Brighton and Beaumaris coalesced in the mid 60s into groups such as the Fauves, including Ross Hannaford; the Rising Sons, with Keith Glass; and the Pink Finks, with Ross Wilson.

Hannaford recalled in 1971 that the Fauves “only knew two numbers”:

We thought it would be funny to start a rock band and we played at this church dance and Ross Wilson sat in with this other band that played there. The guys used to live in the same street where we practiced. It was Keith Glass’s band. We’ve known Keith a long time. Ross started with them and played a bit of harp . . .9

Keith Glass – yet another figure who will play important roles in this story – went on to be guitarist and songwriter in the great Melbourne pop groups 18th Century Quartet (which also featured Hans Poulsen as singer-songwriter) and Cam-Pact; in the mid 70s, together with Wilson, he would also start (and go on to run with his wife Helena) the Missing Link label (the record shop with the same name was a continuation of Archie and Jugheads, which Glass opened with David Pepperell early in that decade).

In 1972, the fortunes of relative newcomer TV broadcaster the 0-10 network would be saved by the scandalous soap opera Number 96; alongside topless women and storylines involving drug use and adultery, the show famously introduced sympathetic gay characters – reputedly for the first time in mainstream television anywhere. Homosexuality was, nonetheless, illegal throughout Australia until the individual states and territories began a piecemeal process of decriminalization starting in 1973. It was therefore a brave, if not foolhardy, move for the Melbourne group Cam-Pact – who identified, in the main, as heterosexual – to flirt with a homosexual ‘image’ several years earlier. It came in the form of, firstly, their name (they were originally the Camp Act), and secondly a mouth-to-mouth kiss between bassist Mark Barnes and guitarist Chris Stockley in the film clip for their first single, ‘Something Easy’ (1967). Such ‘shock tactics’ paved the way for other groups – the Zoot, for instance – to make an impression with similar attention-grabbing ideas. Cam-Pact themselves were impressive and unusual; they were predominantly a soul group, but they also delved into psychedelic pop.

By the time Mike Rudd’s group Chants R&B arrived in Melbourne from Christchurch towards the end of 1966, individuals like Wilson, Hannaford and Glass had graduated from school dances and very local venues like the Beaumaris Community Centre’s venue, Stonehenge, to become players on the Melbourne scene. Hannaford had joined Wilson in the Pink Finks, and in early 1967 they formed a new band together, Party Machine. Rudd heard Party Machine playing, ‘maybe it was at Tenth Avenue and I thought, “this actually sounds like a really good band, I really love what they’re doing” . . . I just stored that away, and then I heard they were looking for a bass player, and auditioned.’ The group were unusual for the time, not necessarily because they played their own material for the most part, but because they played Ross Wilson’s material, which was provocative and didactic, and also on occasion personal. Wilson’s songs were as unique to his experience and worldview as, for instance, those of Ray Davies. Rudd, who at this stage did not write songs himself, remembers the group was ‘successful to a degree’:

In the early stages we were doing fifty-fifty covers and Ross’s material, and it expanded from there. I think I had something to do with the discussions in the van on the interminable drives from Sydney, saying, ‘Look, we may as well just go for broke and hope to impress industry people – i.e. musicians – with what we’re doing’, because I felt quite strongly that what Ross was writing and what we were playing was so different. And when I look back on it now, it still is. Everyone else was going in one particular direction, a very UK-oriented thing, and Ross was in a different area, probably more towards the States. But it was very different for here. If you listen to it now it’s cute, you’d almost call it psychedelic bubblegum.

Robert Wolfgramm, a schoolboy in the late 60s, and raised as a Jehovah’s Witness, experienced a debauched (in comparison to his usual existence) weekend to which the Party Machine contributed when he attended a show at Piccadilly’s, a club based at Ringwood in Melbourne’s outer east:

First on stage was the Party Machine featuring Ross Hannaford, Ross Wilson and Mike Rudd, followed by the highlight for the outer urban ‘heavy’, ‘progressive’ set, Lobby Loyde’s Wild Cherries. What with mostly mod girls and sharpie boys, 20-minute jams, and throwing-up, I knew this was ‘happening’. I might have been the only brave hippie there, but this really was ‘the scene’. And I was in it. Of course, I couldn’t keep my mouth shut and once the stories of my ‘wild’ weekend in Ringwood reached back to the power centre of the Academy, that was the end of weekends away. I’d been let off the leash to be ‘a witness’ in the big smoke, but had been trashed by it. As it turned out, I didn’t need another Piccadilly’s experience; one was sufficient to cast my reputation among my peers as a hippie-druggie. On the sniff of a vomitus handkerchief, I became famous.10

Another incident in the Party Machine’s life – as described by Hannaford in 1971 – shows the kind of aggression a band might encounter when trying to confront and provoke an audience, rather than merely pander to them. This remains, of course, a working hazard in entertainment:

A fight we had when we played in this nasty place . . . this joint, like Tenth Avenue. There were sharpies and all these nasty little girls. They kept putting shit on Mike, saying he was dirty; it was stupid, because he’s a clean guy. Also my amp, which I used to put on a chair, the whole thing fell over while I was playing and everyone laughed. This made me angry, like I didn’t show it, but it was pent up anger. The tune we saved for last, had a long randy solo in it and they were pissing around and rolling on the floor and all that. I was facing my amp and playing guitar, and sort of walking backwards, with my back to the audience, known [sic] there was a mike standing behind me, but making it look accidental-like, when I was walking backward I knocked the mike stand into the audience. You might think that’s an aggressive thing to do, but they were nasty people. There was just a little stage and I was standing on the floor. I was really angry and I was bumping people accidentally. I knew they would get in the way. So they bashed me back and at one stage they had me on the ground and were kicking me and stuff. I got up and swung my guitar around. We finished and although I’d started all the trouble they didn’t pick on me when we were taking out the gear, they bashed up Mike and Russell. Mike got a really big black eye out of it. Nasty. Yes, that is a highlight I suppose.11

The Party Machine leant towards a multimedia approach. ‘The days of four musicians walking on stage and merely playing are fast disappearing,’ Go-Set lectured its readers in early 1968. ‘The emphasis now is on the visual side with the sound playing a supporting, and complementing role.’12 Pip Proud’s withering assessment of 1960s prudery is confirmed by the response to the Party Machine’s most notorious act, the publication of their ‘songbook’, which included two sets of lyrics, ‘I Don’t Think All Your Kids Should Be Virgins’ and ‘Don’t It Make You Sick’ (‘First I got an axe and I split her in two . . .’). The typeset, photocopied ‘books’ were seized by the Vice Squad and the band was attacked in the tabloid press. ‘It sounds so incredibly quaint nowadays’, says Rudd.

The Party Machine broke up in April 1969. David Elfick wrote in Go-Set that Ross Wilson was moving to Britain to join the well-known Melbourne group Procession:

This shock decision came just as the group are receiving the recognition they deserve. Last year their songbook caused a sensation but after that died down, their popularity waned . . . Lead guitarist Ross Hannaford has decided to return to art school. The two remaining members of the group, Mike Rudd, bass guitarist, and Peter Curtin, drummer, will keep together and form another group. They will be joined by David Skewes (ex Mantra) who will be on a Hammond organ . . .13

This last assemblage was to be the beginning of Spectrum, who will be discussed in greater detail in chapter 8.

Procession, the band Wilson left the Party Machine and Melbourne to join, has a long and involved history that begins with Brian Peacock, guitarist and singer in New Zealand’s biggest mid-60s group, the Librettos, flying into Sydney. It is best told in his words:

I have a vivid impression of arriving in Sydney at night time and seeing the city from the air, which was mind-boggling. We spent the next year, at least, living in abject poverty in Sydney, keeping up the image in New Zealand. Trying to live this double life of successful pop stars when in reality we were doing second jobs like car washing and so on in Kings Cross. We basically became a backing band, guns for hire in the Sydney leagues clubs. I remember working with Lucky Starr, who was hot on the heels of his ‘I’ve Been Everywhere’ hit.

We were pretty amazed about the industry built up around the leagues clubs of NSW and Queensland. We were in Sydney, so we could earn really good money in the leagues clubs, but we were also playing the rock venues of the time, from Surf City at Kings Cross down to tiny little bars like Suzie Wong’s, which a lot of the pop groups of the time were working. The money was really poor, the conditions were really poor. But we loved it, money was really just a means to an end in those days, and the Australian industry was pretty grass roots, there was no infrastructure for popular music at that time.

The Librettos were lucky enough to get into some of the Normie Rowe tours, and they went on forever, they’d be three or four months long, typically, he’d do one-nighters in every town throughout the outback. Apart from the major cities, you’d do the Dubbos, Waggas, it was a never-ending slog from one end of the country to the other. We thrived on it. We thought it was great. We were like the opening act on a bill of twenty artists – it seemed like twenty – the Sunshine Review, all the artists that worked on the same label Normie was released through.

Normie Rowe was the biggest star of his kind in Australia in the mid 1960s. He had been discovered by Ivan Dayman; Dayman introduced him to one-time Young Modern songwriting competition winner Pat Aulton, who would become his producer.14 Handsome, with a fine voice and a jovial approach, many of Rowe’s song choices at this time – like those of so many of his peers – now seem stodgy and unimaginative. He certainly got the breaks, even starring in a film made in New Zealand called Don’t Let it Get to You.15 One early band who backed Rowe was the King Bees, which also featured Joe Camilleri.16 Rowe soon created his own permanent outfit, the Playboys.

Dayman managed both Rowe and Marcie Jones, a singer who featured heavily on Dayman’s Go!! Show and played at many of his suburban dances. Rowe and Jones became romantically involved, and Dayman dealt with the situation by booking them tours on opposite sides of the country.17 Later, when Rowe was in the UK, Dayman persuaded his manager there, David Joseph, to withhold Jones’s letters to Rowe, so as to damage their relationship.18

Peacock continues:

Ivan Dayman was the promoter. He was based in Brisbane but Sunshine was a Festival Records imprint so it was all run out of Sydney. Pat Aulton was the main producer. It was like a mini-Motown set-up, we were like the house band for a lot of recordings.

Pat Aulton liked us as musicians, and started using us doing backing tracks for some of the artists on Sunshine. There was Peter Doyle, Marcie Jones, there was a whole lot . . . Mike Furber, though he had a band called the Bowery Boys. I can’t remember which ones we played on and which ones we toured with. We used to back some of those artists live on Ivan Dayman’s shows. I think the link with Sunshine came out of us working for Ivan at his clubs. He had what were called sound lounges all around the country.

They were known as sound lounges, which I think probably originally started with recorded music [being] played in them, but increasingly they had live acts as he built up his roster of artists, and we were probably one of the main ones, because we would go anywhere and do anything in our eagerness to work. Ivan used to take full advantage of it! But we were willing participants.

It was really very ad hoc. For instance, he had a venue up in Brisbane called Cloudlands Ballroom, which was this beautiful old ballroom up on top of a hill, legendary. It actually had some accommodation in the basement below it, and we used to live there when we were up in Brisbane. We played these big shows in the ballroom, and then we’d go down to our little dive of an apartment down below! That used to be our base in Queensland, and Ivan would wander in some day and say ‘I want you to do Toowoomba, then Sydney, then Melbourne’, he’d give us some folded bills, and he’d say – he had this saying we always used to send up – ‘Take the Valiant, father’. He had this old station wagon; we used to throw all our equipment in the back of it, three amps and a drumkit, and we’d fit in the back of a Valiant station wagon and drive from Brisbane to Melbourne in one hit, without thinking anything of it. We’d do a week in Melbourne at one of his venues, then up to Sydney to one of his clubs there and you’d play there the whole week. You’d do these really long sets, starting about eight or nine till three in the morning. So it was a great experience for a bunch of young kids.

We had a radio hit here in Australia – that song ‘Rescue Me’ by Fontella Bass, which we’d been playing for years in New Zealand. During that era the nightclub scene in Sydney was really big, the real true traditional Vegas-style nightclubs, and I remember getting somehow into Chequers free to see Shirley Bassey. This was the mid 60s, and this was the kind of manager we had . . . old-school show business, someone like Shirley Bassey was seen as the epitome of show business. Those things were still an influence on us even though we were taking a completely different path musically. It was still that mixture of putting on a show, a consciousness of that. Then we graduated up the ladder in the Sunshine thing, we became more important, and we got onto the big Normie Rowe tours. That was luxury for us, we were touring in a proper coach, the artists were in a coach, staying in motels, instead of scrabbling round in people’s apartments and on couches.

The Librettos occasionally achieved broad exposure, for example when they supported the Seekers’ second major Australian tour in 1966.19 This may have been where Peacock first made the connections that would result in his becoming road manager and occasional songwriter for the New Seekers in the early 70s. In the mid 60s, however, the Librettos’ lifestyle was still hand-to-mouth.

We’d go back every six months or so to do a tour of New Zealand to restock the coffers. We were living a pretty tough life at the time, eating bread and jam, all sharing one flat in Kings Cross. It was around the time of Max Merritt and the Meteors, and Dinah Lee was doing pretty well around here, and the Invaders – they were the New Zealand acts who were over here trying to break into the Australian scene. So that led on to the Normie Rowe tours, then eventually Normie’s management being taken over by David Joseph, who was a television producer from Melbourne. We were asked to join Normie’s backing group, myself and another guy from the Librettos. By that stage the Librettos got pretty close to the end of their path, a couple of the members had left and we’d replaced them, then we went from being a quartet to being a trio. So the two of us who were original members of the Librettos got asked to join Normie’s band, and that meant our chance to get to England so we decided to do it.

David Joseph had lined up a record deal for Normie with Polydor in the UK so we thought it was well worth while taking up the offer. But it was a couple of the members of Normie’s old Playboys and us, it was never really a great matching up because we were worlds apart . . . we had no ties really to Australia, whereas they wanted to get back to their girlfriends, back to Melbourne.

It was a very interesting time to be in London, we got to see some great artists because of the link with Polydor. Polydor UK distributed the Stax-Volt label amongst others, and we were doing a lot of demos and rehearsal work in the Polydor studios right in the middle of London and as a result of that when the Stax-Volt tour came through the UK, Otis Redding, Sam and Dave, Eddie Floyd, Booker T and the MGs, all those artists, they kicked off the tour with a week’s rehearsals at the Polydor studios in London, So I got to sit in on the rehearsals with those guys for a week. Experiences you’d never dream of – Booker T and the MGs, just incredible! Polydor also had the Who, so I used to bump into Keith Moon all the time going up in the lift, I remember standing side-stage at the Hammersmith Odeon . . . the artists we saw in those years!

Joseph’s schemes for Normie Rowe’s international success fell in a heap when Rowe was called up for national service in September 1967; the tide of public opinion had not yet turned regarding the Vietnam war, as it soon would, and the decision was made that Rowe should serve. Glenn A. Baker postulates that this was a government public relations exercise, and the fact that Rowe was singled out was a secret even to the pop star himself.20 Rowe’s best singles came late in his pop career, with Peacock’s irresistible ‘Penelope’ (1968) and Johnny Young’s remarkable ‘Hello’ (1970). Ronnie Burns’s 1970 hit ‘Smiley’ (‘Off to the Asian war . . . ’), writing of which was credited to Johnny Young (though Ian Meldrum claims that both he and John Farrar were involved in the song’s creation),21 was a mournful paean to Rowe. Burns had, presumably, changed his attitude to Rowe by the time he sang ‘Smiley’; in early 1968 he had been quoted musing cruelly about his rival: ‘Normie Rowe the singer is . . . a manufactured product of excessive promotion, it works but it doesn’t last.’22

In Rowe’s absence, Joseph and Peacock decided to remake the Playboys (who now had two British members, Trevor Griffin and Mick Rogers) as a new band. Local content regulations, and the launch of a new television channel by air travel magnate Reg Ansett, meant an opportunity for a Saturday morning pop show on which the group – now renamed Procession – could perform regularly. This entailed returning to Australia (Melbourne, this time, where Peacock soon got married and started a family) and a chance to relaunch for the international market:

David, being the smart guy that he was, had come up with this idea of what he was going to do after the Normie Rowe thing had fallen through, which was to go back to what he knew – TV production – and he’d come up with this concept which he couldn’t see missing, in that the Australian channels needed it more than anything else. And that was a 4-hour Saturday morning music show which cost bugger all to produce . . .

It was really shoestring – he had a little office in Fitzroy Street in St Kilda, in the building where [artist] Charles Blackman’s studio was, up towards the corner of Grey Street. We were in Armstrong’s most of the week doing the backing tracks for the artists and they would record them and then mime to them . . . that gave us enormous freedom in the recording studio to do our own stuff. We used to knock off all the Channel Ten stuff as quick as we could and then we’d use the nights and early mornings to work on our own stuff. Channel Ten were paying for all the studio time, or David’s production company, I can’t remember which.

Joseph had arranged for a Brisbane pop singer he’d seen supporting Rowe to host the show: the singer was Ross D. Wyllie (it rhymed with ‘smiley’) and the show Uptight; a title which no-one involved seemed to realise was somewhat angsty for a programme of unrehearsed, knockabout pop miming and chat. Wylie was paid a pittance ($60 a week, he later recalled), but his pop career subsequently flourished, as will be seen later in this chapter. He also made an album, Uptight Party Time, credited to Ross D. Wyllie and the Uptight Party Team via ‘four separate recording sessions and countless cans of Fosters.’ A medley of 31 songs (from ‘Satisfaction’ to ‘Flowers in the Rain’ to ‘You Are My Sunshine’), the LP was ‘A Procession Production’ and demonstrated yet again the versatility of Peacock’s group. David Joseph ‘basically saw the two things’ – band and TV show – ‘working hand in hand’, Peacock says:

He knew we wanted to get back to England as soon as we could, and was encouraging us to get as much writing and demoing done as we could. Which is what we did. We put together a whole lot of demos, and then he flew off to the US and the UK and put together a record deal with Philips in England and Mercury in the US. Those labels were allied — all owned by Philips . . . Our sole intent was to get back overseas.

The readers of Go-Set were worried about an air of ‘hype’ surrounding Procession. Canberran Paul Culnane – later a music historian of some note and co-founder of the exceptional Milesago website – wrote a barbed letter to the magazine in 1968 about Ian Meldrum’s overly rapturous review of the group:

Dear Go-Set.

I was appalled at the giving away of ‘instant fame’ to the Procession. Granted I haven’t heard ‘Anthem’, nor experienced what is hailed as ‘sensational’ by Go-Set writers; but aren’t Procession getting the easy way out, when we, the actual people who make groups what they are, haven’t seen or heard them yet?

Surely it is up to us to like who we like or don’t like without it being pumped into our brains by know-alls like Mr. Meldrum, who is so sure of himself he can pass a judgement without us even having heard of the Procession.23

Meldrum’s response was that ‘A certain Canberra-ite should get his facts right and get with it by joining the Procession’.24

Procession’s debut album was Procession Live at Sebastian’s, recorded on 3 April, 1968 – probably before the Uptight record, which was issued the same year. It was ‘the first stereophonic ‘LIVE’ performance album ever produced in Australia’, proclaimed Anthony Knight’s sleevenotes. The album, says Peacock, ‘was to show that we were a good live band, because we knew from our time over there that you had to be able to cut it live, not just be a studio band.’

The idea of making a live album first was part of that plan to get the record deal that we wanted. And to his credit, David pulled it off. We had one of the first major advance record deals signed for an artist that had never left the country . . . And that enabled us to go, when we did go to England, we rented this grand house in Chester Square which is just behind Buckingham Palace in Chelsea. The house was owned by the British Ambassador to Brazil, Lord Russell, and it was very grand – which I think was partly to meet David’s requirements. We all moved in — David and his wife and child, and then the band members. It was a four- or five-storey London townhouse. Grand. The full bit, with the servants’ quarters in the basement. So the multi-thousand dollar advance that we got went a long way towards paying for that lifestyle for the first six months or a year.

The group had signed to Mercury, for whom they recorded their self-titled debut studio album; in the US, the album was released on Mercury subsidiary Smash, home to Jerry Lee Lewis, It was produced by Mike Hugg, the drummer from Manfred Mann. Peacock remembers:

We always thought we were one step away from making it. You always have that hope. And we were doing things, to the best of our knowledge, in the way that we needed to do them. But it just shows that it doesn’t matter how much money you spend on something, if it’s not in the groove . . . I don’t think we ever really made the right record. I don’t blame anyone for it not working. It can be a very random thing.

In some ways it was frustrating . . . I think part of the problem was that we really allowed ourselves to be moved away from our original intentions, in the effort to get commercial success. In Australia we’d been really pretty progressive. We set the agenda creatively. Then we went to the UK and we fell into being pushed around a lot more by the record company and the requisites of the commercial pop world. So I think we lost a bit of direction.

Peacock and Ross Wilson had no doubt crossed paths before (Rudd remembers the Party Machine appearing on Uptight in pyjamas, though this presumably was not the reason the group were temporarily banned from the show). Wilson was, in any case, a well-known figure in Melbourne and Peacock decided he might be Procession’s future.

David eventually gave up and brought his family back to Australia. We then went back to our gigging, just being a real rock group in the back of a transit van up and down the M1 and playing wherever we could get a gig. That’s when we started reigniting the passion that we’d had before. That led to re-looking at the realities of what the group was. I knew about Ross Wilson’s Party Machine, and I was really keen on bringing Ross over to join the band.

I rang him up and told him what we were doing and asked him if he was interested in joining us. I don’t think it was too much of a surprise that he leapt at the chance and came over. I think he was feeling, at the time, that he was banging his head against a brick wall, and the idea of getting away and going to London for a while appealed to him.

Wilson’s decision meant the end of the Party Machine, says Rudd: ‘Automatically. And I don’t think we were that injured – we may have had our noses out of joint for a week but we could see it was an opportunity for Ross and then I saw it perhaps as a possible stage of evolution for myself.’ Peacock picks up the story:

Ross came over and got married. I’d found this fantastic old country mansion at Reigate, outside London, in Surrey. So when he came over I’d already moved the band into this country estate. That was quite fun in itself. It was a beautiful house, really impeccably furnished with a Steinway grand piano in the drawing room and antique furniture throughout. We had to maintain the pretence that it was a couple – myself and my wife and kids – living there. When in fact we had about ten people living there – band members, roadies, girlfriends. Whenever the agent and the owner used to come around to inspect it, we had to bundle everyone into the transit van and pop down to the local pub while my wife and I went through the charade of showing them through the house.

This house featured in Australian director Philippe Mora’s first feature film, Trouble in Molopolis, which starred Richard Neville, Germaine Greer and Martin Sharp. Peacock felt himself a part of the Australasian expat scene, and he was where the action was – London:

During that era we were playing clubs in London which were really upmarket discos. Places like Revolution Club. Just on weeknights, it wouldn’t start until two in the morning, and you’d play a couple of one-hour sets. The A list of London pop society on any given night would be out in those clubs. You’d have McCartney and Lennon and Eric Clapton and people like that turning up to your gigs. Not because we were there, we happened to be playing there, but these were the kind of people who were walking around in the clubs at two or three in the morning. It was a whole other world.

We were basically working to get another record deal. The Philips deal had come to an end. We were out of contract and looking to start over. But the problem was that there was Ross and I and the other half of the band – as it turned out later, it wasn’t obvious at the time – was a bit begrudging of the fact that this guy had been parachuted in from Australia and made the lead singer, when we had Mick Rogers, who was a great singer. I had been doing all the lead vocals before that . . . We had a regular weekly spot at the Marquee, which was pretty big-time in those days –we had a Tuesday night residency there with Yes. So we were doing pretty well live, we were certainly no slouches, but it never really gelled properly. It was like a strange mishmash of Ross’s songs with the much more pop approach that I had to writing.

But I remember some of his songs that we used to do were more [like] Party Machine and Sons of the Vegetal Mother, like ‘Papa’s in the Vice Squad’ and ‘Make Your Stash’.

This last song would later feature on albums by both Spectrum and Daddy Cool.

That tells you were they were coming from. It was a pretty heavily drug-related culture at the time. Acid was prevalent in London. I think the last thing we did together as a band before Ross came back – and this is the desperation state we’d reached – we did this boat trip from Southampton to New York and back on this little Italian steamer, ferrying American students back from their European vacations and then bringing another load over. It was a pretty interesting trip. But when we got to New York Ross and I were — it really illustrated the split in our band — Ross and I went off to Greenwich Village and looked up all the landmarks that we wanted to see and that’s when we discovered macrobiotics . . . when we got back our wives were all astounded when we announced we were only going to be eating brown rice from now on. And we proceeded to do that. But that then led to Sons of the Vegetal Mother and where all that came from.

Not only did Wilson have his macrobiotic philosophy when he returned to Australia, he also had a wife – Pat, who had gone with him to Britain – and a song, ‘Eagle Rock’, which had come to him in a dream and will be associated with him for ever after. Ross (and Pat) Wilson’s next phase is discussed in chapter 9.

CLEVES

Another important trans-Tasman story, this one involving the then-unusual scenario of a woman playing a role as an instrumentalist within a group, was that of the Cleves, who had begun in New Zealand as the Clevedonaires. Unlike Rudd’s or Peacock’s groups, the Cleves did not make a significant impact on the charts, or even sustain a high media profile, but they were present at a number of significant moments in the history of the period, particularly in the presentation of rock/pop music in other media. Gaye Harmon, who played in the band with two of her brothers, recalls that the group decided to relocate to Sydney after they had been swept up in media interest in New Zealand regarding a tour to Vietnam for the purpose of entertaining troops there – a tour they pulled out of when they discovered they’d only been given one-way tickets.

We must have got the travel bug, so with Vietnam a non-starter we settled for going to Australia instead . . . Work had been arranged for us at Cooma in the Snowy Mountains. The day we arrived, we had to play a four-hour set until midnight, then we were told to pack up all our gear and set it up in a nightclub down the road, where we were expected to play until 3 a.m. This was to be a nightly arrangement. Naturally, we weren’t too thrilled about it, so we got in touch with our New Zealand agent, Benny Levin, and he got us out of the deal and found alternate work for us as resident band at the Hume Hotel in Yagoona. So we moved to Sydney.

The Hume is now sheltered accommodation, I believe, but it was a great venue in those days. We loved it there. We played to packed houses, fronting under our new, shortened name ‘the Cleves’ and also backing guest stars like Eden Kane and Dinah Lee. Dinah Lee enjoyed working with us and introduced us to a friend of hers, Bobbie, who was PA to the head of the Cordon Bleu agency, Harry Widmer. It was a great piece of luck, as Harry became our agent and then the work just kept coming.

Harmon recalls that Widmer was key to the group providing music for the soundtrack to Peter Weir’s short film Michael, part of Three to Go, a trilogy exploring individual (fictional) young people’s stories. The songs they wrote for the film were released as an EP, Music from Michael; they also recorded a scintillating self-titled album that ran between prog and pop. The Cleves were versatile in the extreme: in the early 70s, they recorded a single ‘Bonnie, Bonnie, Bonnie – Na, Na, Hey, Kiss Him Goodbye’ with Donnie Sutherland, the ex-jockey who had become a DJ and Go-Set writer; they also recorded jingles and other sessions. Their story in the 70s will be resumed later in this narrative.

THE TELEVISION’S HUNGRY

In subsequent chapters, the power and value of the mid-70s television show Countdown will be discussed, as will the strange misconception in many music and popular culture histories that Countdown was the first ‘real’ Australian rock program, arriving in what had been a music-television desert. Putting aside the fact that music television is, in most of its incarnations, barely something to celebrate, it should be pointed out – if this chapter hasn’t already provided enough evidence – that pop and rock music was very much a part of Australian television by the late 60s. It seems to have been almost de rigueur to give a star his or her own TV show, in fact. Ronnie Burns’s hit with ‘Smiley’ coincided with the announcement of his clip and mime show Now Sound.25 Earlier in the decade, in April 1966, Laurie Allen and Bobby Bright – as Bobby and Laurie – had a number one hit with ‘Hitchhiker’. The pair were then given their own show, It’s a Gas, which first aired in July 1966.26 The program – its name was later changed to the more compelling Dig We Must27 – featured comedy as well as music.

Another beneficiary of television’s embrace of pop was Billy Thorpe, who was briefly discussed in chapter 2 and will feature heavily in chapter 9. In 1965 he had split the original Aztecs and put together a new line-up:

Firstly I got Johnny Dick and Teddy Toi from [Max Merritt and] the Meteors . . . They were pissed off with the lack of recognition they were getting, I guess, so they decided to join me. Also a band from Western Australia called Ray Hoff and the Offbeats were playing in Sydney at the time. So I got the two guitar players from there. Firstly Mike Downs and then Col Risby.28

Thorpe’s live television show, It’s All Happening, was from all reports a vibrant and sensational program featuring not only local acts like the Easybeats but also international visitors such as Neil Sedaka. A few years later, Thorpe griped to Planet’s Lee Dillow that the show’s demise was caused by network politics:

BT: Political scenes by Channel 7 down here which I’d dig you to print.

LD: How do you mean political?

BT: Well they had a teen show of their own in mind with Ian Turpie and all those cats. So if Sydney wouldn’t take that, they wouldn’t take ours. So that was that. An incredible disillusionment for us. Our ratings were so good.29

The show in question was presumably The Go!! Show, which was hosted first by Ian Turpie and then by Johnny Young. The following year, Thorpe acted as fill-in host for The Go!! Show while Young was overseas, and told his audience he was going to drop acid on air. The Minister for Health – via talkback host Mike Walsh – informed Thorpe that he would go to jail if he did. The threat no doubt ruffled feathers and delighted viewers, but it appears Thorpe did not go ahead with it.30

THE WAY THEY PLAYED

In 1966 journalist Maggie Makeig travelled to Hobart with the ambition of finding out how the teenagers of that city were catered for musically. She visited Beachcomber, ‘a big teenage dance centre in Hobart’ – and saw the bands the Falcons, the Silhouettes, the Avantis: ‘Some were good, some were rank amateurs’. She also listed other bands, such as Chaos + Co (‘a basically English group’), the Kravats, the Trolls, the Bitter Lemons, and the Beat Preachers. There were two music shows on local TV, Saturday Stomp and Saturday Party.31

Perth-born songwriter Brian Cadd had recently left Hobart – where he was playing in the Planets – for Melbourne, where Ian Meldrum persuaded him it would be a good idea to change his name to Brian Caine (this didn’t last).32 Later in the decade the Van Diemen label issued records by a number of Tasmanian artists, including Clockwork Oringe33 and Sweaty Betty.34

Each Australian city had its particular scene and style, as well (of course) as its rip-offs and frauds. In 1970, the poet Andrew Jach published a piece in the small press magazine Holocaust called ‘Brisbane your balls have burnt off’. In it he replicates the visceral and to his mind hollow world of Brisbane nightlife, where one might find:

some vain semblance of enjoyment from the

vast array of In places, such as the red orb

the reD ORB

the rED ORB

the RED ORB

thE RED ORB

tHE reD ORB

THE RED ORB

and also

the municipal library

OPEN MONDAY TO FRIDAY TILL TEN

can be obtained35

Jim Keays writes convincingly about the late-60s live music circuit in his memoir His Master’s Voice, describing Brisbane as ‘run by [a] cartel’,36 Ivan Dayman operating a bus with the Sunshine logo on its side, in which he would ‘ferry artists up and down the vast Queensland coast.’37 Brisbane was also oppressive, in Lobby Loyde’s memory: ‘You used to get raided for having long hair, playing loud music, walking sideways and looking bad on a Sunday afternoon.’38 Brisbane had its own TV pop show, Countdown; in October 1967, Dayman’s Sunshine label issued a various artists album called T.V.’s “Countdown”, which preceded Uptight Party Time by a year. The Countdown album featured tracks from future Uptight compère Ross D. Wyllie.39

Any touring band would have to play Sydney, but groups from outside were often ambivalent, even apprehensive, of the venues it offered. ‘Sydney was different,’ according to Keays, who was from Adelaide but lived in Melbourne, the heart of music in Australia at this time: ‘The criminal element ran the strip clubs, the nightclubs and most other venues.’40 Go-Set’s publisher Philip Frazer saw Sydney as ‘old school’: ‘In Sydney the venues tended to be controlled by old time entrepreneurs and record companies.’41

Twice in two years, Sydney’s august Bulletin went out to local clubs to try and whip itself into a state of shock at the goings-on of contemporary youth. In 1968 it exposed the main hives:

In Sydney, at lunch-time, the Op Pop, a cavernous blue-black cellar in Castlereagh Street, with mirrors, harsh bands, and teenagers in what appear to be cast-offs lurking in every corner, is packed solid, and on Saturday nights 600 or more will be found slumped on the steps or milling round the dance floor. North Sydney’s sober purlieus have been enlivened of late by Here, a brash discotheque that is open until well past midnight; the Manly Pacific Hotel is crammed on Saturdays for the Questions, and the P.A. Club at Prince Alfred Hospital jumps to the Castaways group; along the North Shore a string of wine bars and discotheques rivals the more urban attractions of the Hawaiian Eye, the Whisky a Go Go, the Vibes, and Beethoven’s. None of these places can match the Melbourne discotheques, headed by Sebastian’s and Bertie’s, which have superb bands and facilities and feature the liveliest singers in the country.42

In 1970, the Bulletin returned to the Whisky a Go Go, which it declared to be Sydney’s most successful disco, ‘a fitting place for the rhythmic pulsations to be shared in the no-touch, do-your-own-thing that has become the disco job pattern.’ Jonathan’s, an old cinema on Broadway (a road south of the city centre which turns into George Street, central Sydney’s main thoroughfare) with silver walls, ‘plush lounges, shaped Perspex lighting and a sound system of infinite complexity.’ Its ‘ten-man resident group, the Complex, threw away its Sergio Mendes bag and delved deep into the eclectic cornucopia of the “new” rock. The ties and jackets rule was relaxed.’ Other discos, at this time, were Stagecoach, Caesar’s Palace (which Keays describes as ‘a seedy late-night dive in the heart of downtown Sydney.’43 It was the venue where Chain recorded their debut album, Chain Live44), and Caesar’s In Place.45 The Masters Apprentices were also welcomed at Ward Austin’s Jungle ‘and countless suburban dances from Hunters Hill to St Ives and Clovelly.’46

For Keays, Melbourne similarly presented ‘an endless procession of suburban dances. These were held in Mechanic’s Institute Halls, Masonic Halls, Scout halls, town halls – in fact any hall that would allow rock ’n’ roll music.’47 Halls would take on temporary names as venues: Broadmeadows Town Hall was the ‘Palace’48 and later the White Elephant and (as mentioned earlier) Beaumaris Civic Centre was ‘Stonehenge’. Keays later adds Lion’s Clubs to the list of potential venues.49 The large number of venues around the city and its hinterland meant there was plenty of work for bands; however, it also meant that bands had to travel widely – and fast – between shows:

We would do three gigs a night most Fridays and Saturdays no matter what state we were in – stoned or Queensland . . . It was a mad dash to make them all. Each dance featured three bands and there was no margin for error.50

Mike Rudd, who saw enough of this life in his own professional career in the Party Machine and others, can also stand back and critique the practice:

When I first went as Joe Public to Sebastian’s and saw the Loved Ones, I was just knocked out. I thought they were the best thing I’d ever seen. But they’d do the same thing – they’d do half an hour at Sebastian’s, and then off they went, and they’d do maybe two or three spots a night. And that actually killed that band. They cite that as the reason, because they had half an hour’s worth of material, that’s all they did.

The groups’ equipment was, by necessity, relatively portable, according to Rudd:

They’d be using their own equipment, but it’d be tiny. It’d be very similar to what bands are doing today, mostly, which is carrying a little portable amp. The PAs were even portable, but the PAs would be there because they’d be act one or two or three on the night, and they wouldn’t mic anything up. Those were the days! . . . I actually enjoyed those days. Soundwise it was at a reasonable level, you couldn’t get above a hundred watts anywhere, doing anything, so audiences and musicians weren’t being deafened as a matter of course.

Well the Thumpin’ Tum was a tiny place, Sebastian’s was tiny, the Catcher was reasonably large and they probably had a slightly bigger PA than most places, but the technology just wasn’t there, you didn’t have three-way or four-way PAs, it was just column speakers – that was it, that was as dangerous as it got.

THE LOVED ONES AND ‘THE LOVED ONE’

The late 1960s – hippiedom, psychedelia and associated elements – remain iconic and fascinating to many members of the generation which experienced them firsthand and many who have come to them since then. The era has, not surprisingly, been the focus of numerous books and films, both fiction and factual. Iain McIntyre’s Tomorrow Is Today is a particularly valuable and in-depth overview of Australian pop in its wider social context between 1966 and 1970, and is strongly recommended for anyone with a particular interest in that scene. This chapter strives to avoid replicating material from that book, but it is so good that some duplications cannot be avoided. McIntyre’s praise for the Loved Ones – shared by Mike Rudd, whose late-70s band, Instant Replay, did a version of the Loved Ones’ ‘Everlovin’ Man’51 – as an undeniably original and irresistible Australian group of the 60s – is one of these.

The Red Onions Jazz Band was briefly discussed in chapter 2 as an example, perhaps, of a jazz collective that walked and talked like a pop group, with its Dadaist humour and unique personality. In October 1965, with their second album, Wild Red Onions, still unreleased, three members of the group – Gerry Humphrys, Kim Lynch, and the orchestrator of the coup, relative newcomer Ian Clyne52 – went into the studio with former Wild Cherries guitarist Rob Lovett for what was ostensibly another Red Onions recording session.53 To the surprise of their label, W&G, they emerged as the Loved Ones, with a new sound and a new song – ‘The Loved One’. ‘I suddenly found that to me, quite realistically, my roots were in blues,’ Humphrys told Nigel Buesst, ‘so I rapidly learnt to play the harmonica . . . it was R’n’B with baroque classical influences I find it very hard to put a tag on.’54 ‘The Loved One’, patched together in the studio and a perfect example of seemingly artless high complexity in music, was perfect. Humphrys included handclaps in the verse because he felt that without them ‘people are going to get lost’.55

The unusual and non-intuitive nature of the Loved Ones’ material is best demonstrated by Humphrys’ obvious inability to mime to it during the group’s many television appearances: he anticipates exultations that aren’t there and consistently mouths the wrong words.56 Yet it’s clear that Humphrys was the heart and soul of the group, which peaked quickly and died within two years, the victim of its own inexperience and overwork. Clyne had been sacked early in the piece, for being too organised and ambitious, while W&G’s unwillingness to invest in the band, along with the various demands of fame and fortune, proved to be a drag on the group’s creativity, to name but three bummers. In Nigel Buesst’s 2000 film about Humphrys, Lynch complains of having ‘no time to refresh or write new material, half-hour spots . . . the band was stagnating, frankly.’57

Many a time with the Loved Ones, the original inspiration just sounded so much better. That’s why, in the end, we used to compose in the studio. That’s the way I find I can work, personally, Of course it’s a bit of a bind for the musos, because they like to be a little more secure.58

‘The Loved Ones was basically a revivalist group’, Humphrys told Daily Planet in 1971. At one stage we had three records in the top ten. Once we had become successful, we were obliged to play only our records. It was all too commercial, and I got out. It took me two years to recover from that incredible scene.59

The Loved Ones split in October 1967, though they reformed briefly in early 1968 for a 3XY ‘pop happening’ where, it was reported, they wore ‘clothes designed by up and coming gear designer Helen Hooper’ and attended ‘a select orgy in her honour.’60

Writer Barry Dickins met Humphrys in 1969, by which time he was working as a set designer for TV’s Channel 7. He remembered him as ‘a man who made me laugh as soon as I looked at him . . . a Cockney bloke with enormous black eyes and remarkable long black hair and dimples. Gerry Humphreys [sic] and I started working immediately, making a papier maché walnut some 70 feet in length. It was wanted urgently for the Channel Seven Ballet. The stroppy, overweight girls had to emerge from this prop for a scene in The Nutcracker Suite.’ Dickins says Humphries had a cooker and a bar fridge inside the walnut and invited women into it for sexual activities.61 This was only part of Humphrys’ hijinks:

One sunny June day outside the loading bay, Gerry found an old had-it wooden recorder that some musician had turfed in the drain. He patiently repaired it with wire and sticky tape and played jazz on it. Immediately. ‘Far out, man!’ he said to me, and to my surprise he disrobed and got on the top of the rubbish cart and we wheeled him nude into the workshop.62

This story is both wonderful and somehow terrible, because it seems to mark the way in which Humphrys was exchanging his creative role for that of a mere showman. As we will see in chapter 8, he remained a figure in early 70s Melbourne before returning to Britain, more or less permanently, in 1977.

TWO POP EXPOSÉS

There were pop shows, and there were also shows about pop on television. At least two one-off productions from the mid to late 60s enlighten us about this phenomenon in great detail, and set the agenda for this chapter with their rapid montages of exotic cynicism and flamboyant glibness. One is the 1967 television pilot Approximately Panther, directed by Tony L. Lamb. It provides a perfect picture of mid-60s Australia and where it positioned itself as part of the world, and more particularly a portrait of Melbourne, ‘the Mecca of Australian music’ at this time according to Jim Keays.63 Approximately Panther was founded on the vibe generated by the Melbourne-based music magazine Go-Set, though it pushed a little further than the ‘teens and twenties paper’ (of which more later). The program begins with an over-the-top montage of soldiers, people farewelling an ocean liner, a headline trumpeting ‘girl in space’; it then switches to footage of young people, Gerry Humphrys, the Rolling Stones, the edifice of Melbourne’s major railway station in Flinders Street, a violin on a chair, a guitar in a tree, an old car, a new car, a ticking clock, people in a club, and a pinball machine. The show’s host is typing at a table in a small room with books in the background. ‘I’m Douglas Panther,’ he announces, ‘Go-Set’s drunken reporter.’

The show juggles the probably impossible task of delivering an exposé of 1960s youth while at the same time catering to the same youth. Lamb also flags various marketing possibilities for an Approximately Panther TV series, as Panther asks about the spending power of an eighteen-year-old and explores possibilities of cars, fashion and guitars. One of the strangest elements of the film is the inclusion of the Beatles’ clip for ‘Penny Lane’ with occasional and seemingly random bursts of teenage screaming on the soundtrack – another example of Australian ambivalence towards international pop success.

We see Normie Rowe going to London, and the girls who saw him off at Essendon Airport; Panther tells the viewer that Melbourne has become Australia’s ‘teen mecca’, an excuse to segue into the Loved Ones’ ‘Everlovin’ Man’ being played by a 3AK DJ hamming it up in the studio and a montage of DJ faces with a monkey’s face thrown in. Panther is next seen atop a rubbish tip writing his genius work on a portable typewriter. The Loved Ones’ filmclip for ‘The Loved One’ follows, blended into footage of a DJ playing it on the radio and Gerry Humphrys’ excruciatingly poor miming covered up slightly by tree foliage in front of his face. We’re then given a brief tour of Melbourne ‘discotheques’ (pronounced ‘discotheek’ on the soundtrack), including the Garrison and the Thumpin’ Tum. The group Running Jumping Standing Still (with Andy Anderson, once of the Missing Links) is seen, while an unidentified person claims mysteriously on the soundtrack that ‘you can pick up girls, there’s always girls there . . . there are even some of them that are licensed.’ The film ends with footage of people at a party in a Victorian-era house drinking from the bottle and dancing to a stop-start pop song. Tellingly, if you want to see all this frenzied decadence as some kind of furious romp raging against the Vietnam war and the last flickering moments of innocent delight, a candle is burning down.

The Snap and Crackle of Pop was an exposé in Sydney TV station ATN-7’s documentary series Seven Days. Broadcast in June 1968, it’s an hour-long report that reveals the kinds of resistance pop musicians faced in the 60s. Seven Days attacks on a number of fronts, shocked at Lobby Loyde’s Wild Cherries and their preference for improvisation, shocked at Max Merritt and the Meteors’ hair, shocked at how easy it is to film a woman’s sequined underpants when she is dancing and your camera is on the floor. It’s the usual mixture of prurience, squeamishness and jealousy. That said, it provides a multi-faceted overview of the pop scene at that moment in time, from the far-out to the very staid, and to that extent it seems truthful.

A narrative thread that runs throughout the program is the story of a group, the Climax 5, who are temporarily under the wing of Pat Aulton, now transformed from the folk songwriter of early-60s Adelaide into a producer of quick and snappy 45s for Festival. Aulton is himself reasonably dismissive, if not of the Climax 5 themselves, at least of the pop process and his own ‘ears’ when it comes to picking a hit. The progress of the song is followed from two of the group’s members – Nick and Mick – playing it to both Aulton and Jack Arthur at Leeds Music. ‘We use a group sound for the teenyboppers . . . it’s not raucous and noisy, it’s just a happy little song,’ says Aulton.

The Climax 5’s record ‘is one of the 200-odd records released in Australia last month’, our host, writer-director Lance Peters, tells us as he stands, looking slightly appalled, in Edels record shop. The Climax Five are just another of those pop groups with ‘kidney- or heart- or pelvis-shaped guitars . . . occasionally one of the members is a girl . . . she’s the one with the short hair.’ The groups are dressed by ‘that well-known tailor, St Vincent de Paul’ (a second-hand shop) and the music is ‘made up of 90 percent exploitation and 10 percent hallucination.’ The groups, Peters persists, are ‘motivated by such components as sexual frustration, parental neglect, war, despair and occasionally even talent.’

‘Individualism is out, collectivism is in’, according to Peters, and we see some brief footage of the appropriately named group Unknown Blues. The process, we are told, is to ‘buy a guitar, learn a few chords, write a few songs, and then try them out on a music publisher.’ In this scene, like many in the film, the camera performs a loving close-up on every participant’s cigarette.

Flash to the Executives, at this stage a highly successful club group, and more loving camera work on their cigarettes. One year previously, we are told, an industrial designer named Harry Widmer made a bet he could promote a new group (an ‘unknown industrial product’, The Bulletin suggested),64 and the fresh-faced youngsters we see before us are currently enjoying the outcome of this boast. ‘Every group that’s got a top record, we copy it,’ claims one band member. The Executives’ philosophy seems to be: ‘Doing so much material, you must eventually end up with material that’s your own’. The group toured the US in 1968.65 Ten years later former Executive Ray Burton would confess that he didn’t really like the rest of the band ‘as people’. But, he noted, ‘it was a ticket to America, after all.’66 The song ‘My Aim Is to Please You’ is the Executives’ greatest pop moment; much later, a version of the group would contribute the lively theme song to the soap opera The Young Doctors. Burton’s songwriting work is discussed in chapter 8.

The Snap and Crackle of Pop shows us the Executives playing at Cronulla Surf Club in Sydney’s south, a venue run by their manager. A teenage dance, we are informed, brings them $150 a night; a one-night club date nets $200 and a school function $80. So the group make between $80 and $1800 a week, split – after deducting costs – between performers, manager and road manager. ‘It’s no bonanza’, we are told, ‘and popularity is a fickle mistress.’

The film offers a midway proposition between the Climax 5 and the ultra-commercial Executives in the form of Doug Parkinson and the Questions, whose loud amps – ‘almost to distortion level’ – are clearly an issue for Peters. ‘You’ve got to have volume and punch and drive and a feel,’ comments Parkinson, ‘and transmit it to the audience.’ Another member of the Questions – who were, at this time, on the very brink of changing the name of their group to Doug Parkinson In Focus, following a court case over their name – suggests that ‘at the rate we’re going, about 90 percent of the pop musicians today are going to be deaf in five years, either from the band they’re playing in or the in-between discotheque music’. There were, plainly, new issues in the style and power of pop music.

Parkinson and the Questions had previously existed separately from one another. Parkinson’s first group had been Strings and Things, who rose to prominence in 1964 at the Narrabeen Antler, on Sydney’s northern beaches. He then went on to the A Sound, a high school band featuring the siblings Helen and Syd Barnes on bass and guitar; this group recorded a single for Festival in 1966.67 Parkinson was a cadet reporter with the Daily Telegraph at the time. Meanwhile the Questions, who included Duncan Maguire and Billy Green, were playing at the Caropus Room at another northern Sydney suburb, Manly; they had recorded an instrumental album with the imaginative title What Is a Question.

The national ‘Battle of the Sounds’ competition, run by the chocolate manufacturer Hoadley’s from 1966 to 1972, was hotly contested; Parkinson’s group tried three times to win what Planet’s Lee Dillow called ‘Hoadley’s Battle of the Rip-offs’. Parkinson recalled: ‘Winning on our third attempt [in 1969] was unbelievable. I honestly feel that when the Groop won [in 1967] we were robbed. I know we had no presentation but F . . . ! Surely it’s music.’ Parkinson and In Focus, wearing ‘stunning black and red uniforms’, eventually won in competition with the Valentines, Aesop’s Fables (from Sydney), the Brisbane Avengers, and Chain.68 As well as scoring a national hit with a raucous version of the Beatles’ recent album track ‘Dear Prudence’, they received a ‘very exciting film festival award for our Coke commercial.’69 A greatly superior record to ‘Dear Prudence’ was its follow-up, the Billy Green original composition ‘Without You’. In 1971, Parkinson reflected bitterly on the dictates of the market: ‘We now observe the graph as it descends. We put “Hair” on the flip side and it was about here that the crack started to widen. We were bowing to pressure, trying to be popular at the expense of our music.’70

The group produced a number of remarkable, edgy and creative singles, mostly written by Green. The band’s line-up was, unfortunately, erratic. Green, who had threatened to leave the band during its Questions period to become a producer,71 and who later did leave to form another, short-lived group called Rush, says now:

In Focus really split up because of Duncan’s inability ‘to put up with Johnny Dick’s sense of groove’. That was it really. Those two were always fighting. I was the glue, the PR person to put them back together again, magically. Sometimes, backstage, Duncan would be making Johnny Dick feel like a heel, right before going on stage. I would jump in there and do a quick repair job so we could do a good show.

Duncan could be a bastard sometimes . . . hard to believe. Eventually, and inevitably, Johnny quit! He couldn’t stand it anymore. That’s when Doug and Johnny split to England . . .

The story of the band they formed with Vince Melouney, Fanny Adams, is told in chapter 8.

The Snap and Crackle of Pop also covers Melbourne group the Wild Cherries, and its report on this outfit opens a new can of worms: the issue of improvisation and its impact on a professional performance. The Wild Cherries – seen here in their second incarnation featuring Lobby Loyde, who had recently defected from Brisbane-Melbourne group the Purple Hearts – claim in the show that they improvise a lot and play more for themselves than the audience. Author and journalist Craig McGregor, who appears in the film in a boxing ring with, amongst others, Sven Libaek and DJ Bob Rogers, claims to have heard the Wild Cherries many times and opines that ‘they’re a very good pop group indeed,’ adding that – contrary to what many viewers may have believed – ‘you can improvise on an electric guitar just as a jazz musician can improvise on the sax.’

Purple Hearts, ca. 1965

Loyde had first played onstage at the age 17 at Cloudland. As he told Iain McIntyre, his first band was the Devil’s Disciples in 1963 in his native town of Brisbane. As mentioned, his friends and competitors in local talent shows back then were the Bee Gees (‘Gibby and the two little dribblers’)72 and Billy Thorpe. Late in life, Loyde remembered Brisbane – particularly its Blues Club – as being as progressive as Melbourne in the early to mid 60s, possibly more so. His Purple Hearts bandmate Mick Hadley remembers ‘one venue, the Primitif’, but also enough shows in halls and ad hoc spaces to make it ‘pretty vibrant, really.’73

The Purple Hearts were a nationwide sensation; Everybody’s appears to have considered them bad boys, running a photograph of them captioned: ‘Normally they are not to be found on demolished building sites, but we took them to one anyway, because we felt the bricks and steel and mortar suited their uncompromising attitude to blues, and their clunky gear.’74

Loyde claims in The Snap and Crackle that the Wild Cherries’ set is ‘almost totally’ improvised, because the alternative is ‘boring, bores the people, bores us.’ He went on to show his ongoing interest, which he would continue to display in different ways through the 1980s and his SCAM management organization, in the contrasts between art and profit:

If you’re going to play the same old stale thing the same way every night you get pretty sick of it, especially when you’re lazy like us and you don’t learn that many new songs . . . Even the most successful pop groups, that claim they make a fortune, don’t. There’s no money in this country. If you got a number one record you’d be lucky to get $600 out of it, even if you sold 50,000 copies.

From the boxing ring, Libaek commends Max Merritt and the Meteors, in part for their jazz inflections: band members Stewie Speer and Bob Birtles (not to be confused with Beeb Birtles, who hit it big in the 70s with the Little River Band) both have a jazz background. The Snap and Crackle take on Merritt and the Meteors is that they’re the ‘oldest pop group in Sydney,’ with an average age of 33; Speer was forty at the time.75 It is unclear when this interview snippet was filmed but it seems likely to have been before a major car accident near Bunyip, east of Melbourne, in June 1967, during which Merritt lost an eye, Speer suffered damage to his hands and had his legs crushed (Merritt joked: ‘Stewie had what they called scrambled legs’), and Birtles acquired a permanent limp. Only bassist Yuk Harrison was relatively unscathed.76 The group continued valiantly, and were even given the prize, in 1969, of a four-part ABC-TV concert series, just before they relocated to Britain, identified by Merritt as ‘an easy place to lose bread’.77

The program goes on to state that ‘the pop world today is a mini-matriarchal society’ – by dint of the young girls who, as consumers, ostensibly control it. When it comes to girl singers – Lynne Randell and Cheryl Gray (later known as Samantha Sang) are held up as examples) – we are told that they are ‘small, cute and plain’.

The Snap and Crackle then profiles Johnny Farnham, shown being interviewed on the new northern NSW television station ECN8 while out touring with the still ubiquitous Col Joye. Farnham speaks in quotable quotes that acknowledge both the extremely surreal lot of the pop star and his gratitude at being so loved:

Last night we played Tamworth and I got the sleeve of my shirt ripped out . . . the fans made me and I love every one of them . . . I haven’t been mobbed very often – I’ve been in the business just since the record’s come out – but I, confidentially, love it . . . I was a plumber for two years before I was a singer – even now I don’t have the nerve to go up to a girl and ask her to dance with me.

We see Farnham and a scratch band rollicking through ‘the record’ in question, ‘Sadie (The Cleaning Lady)’ which, of all the records and songs dismissed as wanting in this book, is probably the worst: it is shallow, smarmy and snide, a sub-George Formby music hall dud without even a redeeming double entendre. A novelty song poking fun at a woman who works in a dreary and unpleasant job, it rather undermines the ‘matriarchal society’ tag, though in his live rendition Farnham does at least veer away from the record to declare ‘I love you though you’ll always be a cleaning lady’(!).

Farnham has been smoking since he was five;78 he migrated to Australia with his family at the age of ten. He was at school when he joined the Mavericks, and a plumber’s apprentice when his second band, Strings Unlimited, began playing.79 A show of theirs in country Victoria got them attention from accountant-turned-manager Daryl Sambell, while an EP they recorded got them noticed by an advertising executive hoping to find a distinctive voice for a television advertisement for Trans-Australian Airlines. In both cases, the attention was really directed at Farnham, who went solo in 1967 and released ‘Sadie’ towards the end of that year. The current affairs program 4 Corners devoted a programme to showing – much like The Snap and Crackle’s coverage of the Climax 5 – ‘how a record company promotes an unknown.’80 This, along with manufactured outrage from DJ Stan Rofe, who insisted he hated the single,81 helped ‘Sadie’ become the biggest selling Australian record of 1968.