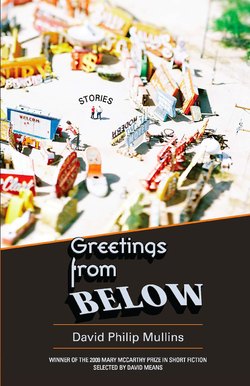

Читать книгу Greetings from Below - David Philip Mullins - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеLonging to Love You

ALL AFTERNOON HE THOUGHT OF HER, EAGERLY IMAGINING the details of her body: her height, her weight, the color of her skin, the curves of her legs, hips, breasts. Now, as Nick walks west through the Tenderloin, nearing the corner of Taylor and Eddy, he feels a prick of anxiety at the back of his throat. Brief but dispiriting—always causing him to second-guess himself—it’s a familiar sign that he’s doing something he knows is questionable. A cool breeze picks up, heralding the coming autumn, but Nick feels sweat surface on his forehead. He’s unsure if he should turn back or carry on. Each building he passes is a liquor store or a laundromat or a bedraggled old flophouse with a neon Vacancy sign. He hurries by them, late to meet My-Duyen, the Vietnamese masseuse he telephoned by way of the yellow pages, a call girl who refers to herself as the “Asian Sensation.”

The address is 155 Golden Gate Avenue, between Leavenworth and Jones. When he spoke to her earlier today, she told him to call her from the curbside pay phone at a quarter past eleven. “Generous men only,” she said, as if he weren’t aware that her repertoire extended beyond the domain of benign, legal massage. “Full service,” she added. He stared at her photoless ad in the fluorescent light of his kitchen. “I’m Jack,” he told her, giving her his father’s name, whispering into the receiver as though someone were around to hear him. “My-Duyen,” she replied. She mewled and moaned. When he asked her what her name meant, if anything at all, she paused before answering. “Beautiful,” she said, and Nick hoped the name was appropriate.

At the pay phone, he digs a scrap of paper from his back pocket, dials the number he copied from the telephone book. The building is a handsome brick Edwardian with a big stone portico—the kind of building normally found in the Western Addition or Pacific Heights—out of place in the Tenderloin, as though it’s lost or slumming. The block is alive with people walking in twos and threes, loitering in doorways, slinking in and out of a corner bar down the street whose windows have been painted black. After several rings, My-Duyen picks up. “You’re late,” she says. It’s eleven-twenty-five. “Second floor, apartment seven. I’ll buzz you in.”

Ascending the stairs, he finds it difficult to lift his feet, his legs solid with apprehension, and the climb to the second floor seems to take an eternity. For all his unease, Nick is shuddering with excitement, hardly able to believe that he’s finally going to lose his virginity. At twenty-three, he considers himself a misfit—an anomaly. Most people spend their college years partying, having sex. Nick spent his reading books in the university library, or else playing Tetris, or The Legend of Zelda, or Dragon Warrior, adrift in the fictive worlds of novels and video games. He reads less these days but plays Nintendo more than ever, an hour or two every night. Of his small group of friends, he’s the sole virgin, a word he repeats so often in his mind that it sometimes bears no meaning, the two syllables bouncing hollowly off the walls of his consciousness, morphing into other, similar-sounding words: burgeon, sturgeon, Virginia. It’s a Saturday, and most of the people he knows are out on dates, spending time with boyfriends and girlfriends. Nick himself has had only one girlfriend—the German exchange student he took to his high-school prom, a thick-ankled Protestant who was saving herself for marriage—and despite his every attempt to negotiate at least a one-night stand, he wakes each morning alone. That he’s resolved to pay for sex only magnifies his long-established feelings of inadequacy and self-loathing.

The door is ajar, a black number seven hanging upside down above the peephole. He steps into the apartment, clears his throat.

“Close it behind you,” My-Duyen says, drawing curtains across a giant bay window. Music is playing softly on a stereo, a jazz composition he doesn’t recognize. She turns to face him. “You must be Jack.”

He left home after high school, vowing never to return, not even to visit. Growing up in Las Vegas, he used to envision the day he would board a plane as an adult and fly off to some better city, escaping forever that place of false hopes and ever-changing luck—a place with more churches per capita than any other city in the United States and a suicide rate twice the national average. During Nick’s first semesters at USC those two statistics would interlace in his mind, relevant in some way to his newfound freedom. He moved to San Francisco a little over a year ago, after graduating with a degree in comparative literature, and has decided that no place is without the potential to let you down.

His apartment, a small studio, is on the top floor of an old white-brick building that overlooks the Powell Street cable-car line, a twenty-minute walk from the converted carriage house in Cow Hollow where he works as a copy editor for a weekly trade magazine called Footwear Today. Every so often he has a beer or two at Salty’s, a seafood restaurant around the corner from his apartment building. Down the hall from the dining area, the restaurant’s bar stands at the back of a large wood-paneled room that’s always darkly lit, its low ceiling supported by four rectangular pillars that make you feel as though you’re sitting below a pier. The walls are hung with fishnets, anchors, and oars, with mounted marlin and tarnished brass astrolabes, and at the end of the bar a model lighthouse stands beside an aquarium that showcases an assortment of sad-looking lobsters, piled against the foggy glass. He likes the kitschy maritime atmosphere, and has taken an interest in the new bartender there, Annie Peterson. She’s blonde and tan, and her face glows in a corner of Nick’s mind (big blue eyes, a full-lipped mouth, a tiny knob of a nose), hurtling to the fore like a shooting star when he least expects it. Though he’s only known her a short time—two, three months—he thinks he might love her.

The other night, Nick was sipping a Redhook when Annie asked him, “What happens if you’re in a car going the speed of light and you turn the headlights on?”

“No idea,” he said, and shrugged.

“Stumped again,” Annie said, slicing lemon wedges on a plastic cutting board. She wore faded blue jeans and a white oxford shirt, her shoulder-length hair sticking out from beneath a purple wool beret. It was eleven o’clock, and Salty’s had emptied out for the night. Roy Orbison sang “Blue Bayou” on the jukebox.

“Lay another one on me,” he told her. “Scramble my brain.”

Annie looked up at the ceiling, set the knife down on the cutting board. “Let me see,” she said. “Let me think.”

She has a fondness for paradoxical questions—owns a small book of them that she keeps beneath the bar—and Nick finds it both puerile and endearing that she’s committed so many to memory. She never tires of watching him labor to assemble a response, narrowing her eyes, placing a slender finger to her lips. Annie’s favorite question of all time: Can a person drown in the Fountain of Eternal Life? Her second favorite: Can God create an object so heavy that even He is unable to lift it? Nick likes obliging her with his earnest attempts at reason, though as often as not he capitulates with a shrug.

“I think I’ve already asked you all the ones I know,” she said, then reached down and pulled the book out from under the bar: Persistently Pesky Paradoxes.

“That alliterative title might have you thinking it’s a book of tongue twisters,” he said, trying to sound smart—trying to impress her—but Annie said nothing in return. She closed her eyes, opened the book to a spot somewhere near the middle. “Bop-bop-bop,” she said, scanning a page. “Here’s one. ‘In order to travel a certain distance, a moving object must travel half that distance. But before it can travel half the distance, it must travel one-fourth the distance, et cetera, et cetera. The sequence never ends. It seems, therefore, that the original distance cannot be traveled. How, then, is motion possible?’”

“That’s an oldie,” Nick said, finishing off his beer. “Even I’ve heard that one before. Where’d you get that book, anyway?”

“Ricky gave it to me. A long time ago, when we first met. It was a gift.”

It’s been six weeks since Annie broke up with Ricky, a taxi driver and aspiring sculptor of whom nearly everything reminds her: the restaurants and movie theaters they used to frequent as a couple, the big yellow taxis that weave through the crowded city streets, the outdoor sculptures at the Embarcadero and Golden Gate Park. He still gives her gifts, lockets and fountain pens and glass figurines that he leaves wrapped in her mailbox, and several times a week he calls her at home or at work, begging to be taken back. The breakup was a result of Ricky’s infidelity: Annie caught him in the act with his best friend’s sister. He had given Annie a key to his apartment, and she walked in on them one night after her bartending shift, the two of them half-naked on Ricky’s kitchen floor. She still loves him, she’s said, and wishes she could forgive him for what he’s done. Nick adores the sound of Annie’s voice, but when she says her ex-boyfriend’s name he always wants to laugh. “Rick,” “Richard,” even “Dick” he could accept. But a grown man who goes by “Ricky”?

“You know what I think?” said Nick.

“I’m afraid I don’t.” Annie closed the book, replacing it beneath the bar.

“I think I’m going to write Ricky a letter.”

My-Duyen is indeed beautiful, with bright green eyes and tea-dark skin and the muscular calves of a bicyclist, her hair shaped in a wedge. She wears a red knee-length dress, open at the neck, and stands barefoot on the wooden floor. The apartment, a studio not much larger than his, reminds Nick of a chapel: low-burning candles on every surface, the walls aglow with the solemn guttering of a dozen tiny flames. There’s a couch, a coffee table, a bookcase, a full-size bed. On a nightstand four wrapped condoms are stacked like casino chips beside a roll of toilet paper. My-Duyen takes his wrist and leads him to the bed.

“Sorry I was so short about being late,” she says. “It’s just that I have a schedule to keep, appointments all night long.”

She’s thirty or so, not young but not old either. Mature, he thinks, like a friend’s big sister. Nick is unable to take his eyes off her, and feels lecherous and rude staring the way he is. He can’t quite say what it is that draws him to them, but a shiver passes through him whenever he encounters a woman of Asian descent. Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, Korean, Thai, Vietnamese—the particular origins make no difference. An irrepressible hunger comes over him, and he can think of nothing but sex. He sees them in Chinatown and Union Square, young Asian women with sleek black hair and soft-looking skin—sees them jogging up and down Powell, hard-bodied and sweating in tight T-shirts and high-cut shorts, their wiry legs bowed like parentheses. Nick often pictures these women when he masturbates, and he’s spent a small fortune at the new sushi restaurant in Cow Hollow, where he’s taken countless lunches simply to eat in the company of the all-female Japanese waitstaff. Now, looking at My-Duyen, he forces a smile to calm himself, the shiver lingering in his limbs like the aftereffect of an electrical shock.

“I would’ve been here on time,” he says, “but I got a call on my way out the door.” He doesn’t want to admit that he was playing Dr. Mario, only moments away from reaching the coveted twentieth level, when he realized the hour. He doesn’t want to say that as much as he looked forward to meeting her, he was on an unprecedented roll and thought for a split second about standing her up, staying home and seeing how much farther he could get. “I walked here as fast as I could.”

“I don’t serve alcohol, but I can get you a soda if you’d like.”

“No, thanks,” Nick says, folding his hands over his lap to hide his arousal. Sitting beside her at the edge of the bed, he can smell her citrus-scented perfume, a trace of mint on her breath.

“Well then,” she says. “Before we get started, I think you have something for me.”

Over the telephone she never specified an amount, and so Nick brought only what he could afford, a hundred dollars. He hands My-Duyen the money—three tens, four fives, a fifty—and she counts it out, nodding amicably.

“This’ll do,” she tells him, and places the folded bills into the nightstand’s drawer. “Now we can relax.” She scoots closer to him, caresses his arm with the tip of her finger. “What is it you came here for?” she says.

“How do you mean?”

She gives him a slow, off-balance smile. “What would you like to do to me, Jack? What would you like me to do to you?”

“A letter of what kind?” Annie said, palming the lemon wedges into a pile.

“I want to make him jealous,” said Nick. “Tell him we’re getting married and he isn’t invited to the wedding. Tell him we’re a thing, you and I, even though we aren’t. Generally, I’m not such a vengeful dude, but wouldn’t it feel good to make Ricky feel bad?”

Around her, Nick often talks in a manner to which he isn’t accustomed—feels more confident, almost cocky, though he can’t say why. She’s out of his league for sure, but he’s never been intimidated by Annie’s appearance. Nick knows he isn’t handsome, not in any classical sense, but he’s reasonably desirable, he’s always thought: dark-haired and tall, with a genial, long-toothed smile he’s cultivated in adulthood. Every now and then he catches himself wondering what her ex-boyfriend looks like—wondering who Annie finds more attractive, him or Ricky.

“You’ve never even met him,” she said. “He’s actually not a terrible person. He just did this one terrible thing. When I think about it, I was really happy with Ricky. Happy in a way I’m not sure I could ever be without him.”

Nick and Annie have had dinner together outside of Salty’s, have shared nightcaps at nearby bars, though only as friends. Whenever he takes her hand her fingers wiggle free of his grasp, and when he tries to kiss her she turns sharply away. “Not yet,” she always says. “It isn’t the right time. A new boyfriend’s the last thing in the world I need at this point in my life.”

In truth, Nick’s attempts to hold her hand and to kiss her have been somewhat strained. Despite his feelings for her, he isn’t sure he’s attracted to Annie—isn’t sure his interest in her is carnal. She’s an attractive woman by anyone’s standards, but she isn’t Asian, and there are too many times when he looks at her and feels no shiver throughout his body, no hunger for sex, only a contentment so deep that the second they part Nick longs to be near her again. He’s never quite certain, then, if love—romantic love—is the right thing to call whatever takes hold of him when he thinks of her, when he’s around her. He can make no sense of his preoccupation with Annie, any more than he can make sense of his fixation with Asian women.

Annie took his empty beer bottle, tossed it into a recycling bin behind the bar. “Another Redhook?”

“What’s stopping me?”

She got Nick his beer, placed it on the round cardboard coaster that read “Salty’s” in big turquoise letters. Then she set to tidying the bar. He watched as she worked through a row of foam-stained pint glasses, plunging each glass into a sink full of soapy water, rinsing it under a faucet, then leaving it to dry on a long white towel. Heady from his third beer of the night, Nick said, “I love watching you move.”

Annie rolled her eyes, drying her hands on the tails of her shirt. “I miss the guy,” she said, and sighed. “I’m an idiot, but I miss him.”

Nick took the coaster from beneath his beer, flicked it back and forth against the tip of his thumb. “Writing utensil, please,” he said, and held out his hand.

Annie gave him a pen. He laid the coaster down on the bar, blank side up. Dear Ricky, he wrote.

Sex, he wants to say. I came here to have sex. But somehow the word seems crass, despite the urgency of his desire and the fact that he’s with a call girl. Perhaps because of all the candles, Nick feels as if he’s on a date, as if they’ve reached some decisive juncture that might require him to initiate foreplay. He should know how to act in the presence of such a woman, he thinks: he is, after all, from Las Vegas. But as a teenager he could never bring himself to solicit a prostitute, no matter how much he wanted to, no matter how many of them he would see walking the streets downtown. He wonders what about him has changed, how it was that he picked up the telephone earlier today and dialed this stranger’s number. “Are there options?” Nick asks. “Is it up to me what we do?”

“You’re the customer,” My-Duyen says.

“I guess I’m not sure how we’re supposed to begin here.”

“Let’s try a different angle. What are you into?”

“Anything, I suppose. I mean, within reason.”

My-Duyen laughs, as though his answer were the punch line of a joke. She rests a hand on the small of his back. “How about this. You undress and get under the covers, and I’ll take it from there. We’ll skip the massage, OK?”

“Yeah,” Nick says. “Good.” He never expected a massage, and finds it unusual that she maintains the pretext of her yellow-pages ad. He takes off his clothes and slides into the bed, watching as My-Duyen shimmies out of her dress. Naked before him, she pulls the comforter down to his knees, the sheet domed over his crotch. Then she pulls the sheet down too, and his swollen penis is exposed. It looks bruised, as if it’s been slapped around or stepped on, the shaft a rash-like red, the head darkened to a purplish hue.

My-Duyen’s breasts hang sublimely from her body. Between her thighs is a vertical strip of pubic hair, the skin shaved clean around it. She lies down next to him, her leg brushing his, and suddenly Nick feels as if his insides are being liquified in a blender. It’s the same way he’s felt roaming the aisles at Big Al’s, an adult bookstore on Broadway, where he goes several times a week to flip through the pages of Orient XXXpress or Kung Pao Pussy or Filipino Fuck, surveying the glossy images before rushing to the Burger King across the street, slipping into the men’s room, and masturbating in a stall defaced by graffiti and glory holes, sometimes evacuating his bowels just after he comes.

“Asian Sensation,” he says, the words tumbling accidentally from his mouth.

“What?”

“That’s what you called yourself. Over the phone.”

“Oh, right.” She props herself on an elbow, flattens her hand across his stomach in a tender sort of way. Looking down at his erection, she seems to think for a moment, then says, “Tell me you love me, Jack.”

“I’m sorry?”

“Just say it.” Her voice quivers. She lowers her face. “For me.”

What reason could she have for asking him to say such a thing? Is she putting on some kind of act, he wonders, a show of emotion meant to heighten his excitement? “I’m not sure I understand,” Nick says.

She still isn’t looking at him. “Three simple words,” she says, nuzzling up to him like a cat, curling her warm body into the crook of his arm.

“It’s my first time,” he tells her, trying to change the subject, though he isn’t sure why he’s chosen this, of all things, to say. Under normal circumstances he keeps his virginity a secret, hiding it from the world as he might some sordid deed from his past. “I’m a virgin,” he says.

“I figured as much. It’s nothing to be ashamed of.” She reaches down and takes hold of his erection. “Pretend I’m your girlfriend and we do it all the time. Pretend you’re going to fuck me,” My-Duyen says, “because you love me.”

Nick’s heart leaps. His lust for her sharpens to a point, and he feels another prick of anxiety at the back of his throat. He’s been getting it since childhood, this tiny remonstrative prick, anytime his actions have threatened to further diminish his self-regard.

“Please,” she says. “It’s a thing I have.” She kisses his chest now, once, twice, three times. He can feel himself bulging in her hand, conforming to it. “I need you to say it.”

“OK,” he whispers, trying his best to keep from coming. “I love you.”

He stayed until the restaurant closed, then walked Annie home to her apartment in North Beach, fifteen blocks away. In Nick’s back pocket was the short letter he had written to Ricky, the coaster creased into a half-moon beneath his billfold.

“Why don’t you come up,” she said as they approached her building. She shrugged her shoulders, a breeze riffling the ends of her hair. “It’s only eleven. I could use a glass of wine.”

“Great,” said Nick, excited by the invitation: Annie had never asked him up to her apartment before.

It was warm and spacious, a one-bedroom with high ceilings and a recessed balcony. Against one of the walls stood what appeared to be an arts-and-crafts project of some sort. Two yellow pipe cleaners sprouted like antennae from a white Styrofoam ball the size of a desktop globe. As on a tee, the ball sat atop a Quaker Oats container that rose like a little silo from the inside of an orange Nike shoe box.

“Mi casa,” Annie said with a sweep of her hand. She took off her hat, her coat, hung them on a hook beside the door. “Welcome.”

“Nice place.”

“Rent control and tips,” she said. “How else could I survive in this city?”

Nick nodded at the arts-and-crafts project. “Interesting furniture.”

“Ricky’s first sculpture. ‘Evolution,’ he calls it.” She clicked her tongue. “I’ve been meaning to get rid of that thing for a while now.”

Nick had always assumed that Ricky’s medium was either plaster or ceramic, not cardboard or Styrofoam. He looked the sculpture up and down, tapping his chin. Then their eyes met and they both broke into laughter.

“Fine,” Annie said. “So he’s not the best sculptor in the world.”

She opened a bottle of merlot, poured them each a glass as they settled in next to one another on her small leather couch. The cushions were dry as saddles, faded to a light coffee-brown, and creaked whenever he made the slightest adjustment of his legs. They were talking about the letter to Ricky when Nick noticed the Atari 2600 on the bottom shelf of her television stand.

“Read it to me,” she said, nosing the wine. “It was sweet of you to write it.”

She had been busy closing up the bar, and Nick hadn’t had a chance to show her the letter. But he could tell that he had managed to charm her, that she had taken as some kind of gallantry his juvenile wish to make her ex-boyfriend jealous. He thought about kissing her, which he hadn’t tried to do in a couple of weeks. Not yet, he imagined Annie saying. It isn’t the right time. “You’re into video games?” he asked, pointing to the Atari.

“Kind of,” she said. “I don’t know. I bought that thing at a garage sale in Berkeley. It made me nostalgic. They threw in a bunch of cartridges for free.”

“Let’s play something,” Nick said. “What do you have?”

“First the letter. Get it out.”

“Only if you promise to send it.” He sipped his wine. “I hope I didn’t write it in vain.”

“We are not mailing that coaster to Ricky.”

“You haven’t even heard what it says yet,” he said, and took the coaster from his pocket. He unfolded it, straightened his back against the noisy couch. “‘Dear Ricky,’” he began. By the time he had finished the letter—the gist of which was that Annie and Nick were engaged to be married, that Annie hadn’t deserved to be cheated on, and that Ricky would do well to leave her alone—Annie had her head on Nick’s shoulder, her arm draped across his leg. She had never been so physically affectionate with him before. Nick waited for some sign of arousal—a tingle in his groin—but he only felt happy. It was a relaxing sort of happiness, a concentrated warmth that trickled into every crevice of his body, like the slow pervasion of heat from a shot of bourbon: what an elderly man might feel for his wife, he imagined, after half a century of marriage, sexual desire replaced by the comfort of long-term commitment. To call such a feeling anything less than love seemed to suggest a limited interpretation of the word.

“What if I start asking people to call me ‘Nicky’?” he said, tossing the coaster onto the coffee table. “Actually, my mother calls me that, so who am I to judge?”

She patted his knee. “Jungle Hunt,” she said, sitting up from the couch. She refilled their glasses, setting the bottle down on the coaster. “How does a little Jungle Hunt sound to you?”

“Haven’t played it in eons, but I’m sure I can hold my own.”

Annie crawled across the carpet to the television stand.

“You shouldn’t wear makeup,” he told her, watching her thumb through a plastic box of cartridges. A thin layer of foundation coated her cheeks, giving her skin the appearance of fine suede, and her lip gloss made her lips look as though they were wrapped in cellophane. “You’re pretty anyway.”

“If that doesn’t sound like a line.”