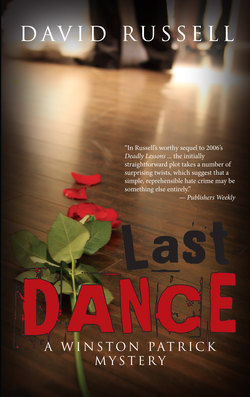

Читать книгу Last Dance - David Russell W. - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Eight

ОглавлениеIt’s difficult to imagine my day could have gotten much worse than it already was. Not to be whiny, mind you; I recognized Tim’s day was probably much more agonizing than mine. Still, when I got home I was greeted by Polish Sausage as I stepped off the elevator into the foyer. I was hoping that my weekend would be less stressful than my violent week, but the sight of our building’s limping strata chair thumping towards me was not a good omen. I was ready to abandon my mailbox in order to avoid the inevitable complaint, but before I could back onto the elevator again, the door slid shut and I was trapped between Canada Post’s euphemistically described “super boxes” and the aforementioned walking pork product.

“Oh, Winston,” he began, as though he had unexpectedly come across me as opposed to staking out the lobby waiting for whichever resident he could annoy on any given afternoon.

“Hello, Andrew.” Still couldn’t get up the nerve to call him Polish Sausage to his face. In my battles between maturity and bravado, somehow maturity always wins. Or being a big chicken.

“I wanted to talk to you about something.”

“That seems a given every time I see you.”

“Yes, well, I’ve been trying to reach you all day.” I had no response to that, so I said nothing. Sausage couldn’t take the silence more than a few seconds. “I haven’t been able to reach you.”

“I know.” He looked confused, and this time I couldn’t take the silence for long. “See, if you had reached me already, I’m sure I would have remembered.”

The silence was uncomfortable enough for both of us, so I decided to leave. It didn’t work. Despite Sausage’s alleged infirmity, he was able to poke his way around our building — his kingdom — at speeds that made subtle avoidance of him impossible. Nothing short of breaking out into an all-out run was going to keep him from keeping up with me. Of course, if he ran after me, that could settle the nagging question of the validity of his disability once and for all. Before I could reach a decision, Sausage had followed me onto the elevator. “What is it you wanted, Andrew?”

“Your measurements,” he replied matter-of-factly.

“That’s a bit personal. Shouldn’t you at least buy me dinner first?” It was clear that Sausage got my joke, but he didn’t laugh. I was convinced Poland must be a very dull place.

“For one with such an upbringing, you certainly are crude,” he informed me.

“Indeed.”

“We need to have the measurements of your living room area for the drywall contractor.”

“It’s about twenty-by-fourteen,” I told him as the elevator door opened to the third floor.

“We need to be a little more exact than that.”

I stopped and turned to face him in the elevator, preventing his exit. “Fine. Leave me the telephone number of the contractor, and I will set up an appointment.”

“That isn’t necessary. I can simply come in and measure it. I have my tape with me.”

“Nope. Name. Number. Appointment. In that order.” Sausage’s face began to bloat as his anger emerged. It made him look even more like a sausage. Before he could say anything else, the door to the elevator closed in response to a summons by someone on another floor. Thank god for small mercies. Silently congratulating myself for limiting our conversation to less than two minutes, I rounded the corner to find an even less inviting sight outside my apartment door.

Sandi.

At seven months pregnant, Sandi Cuffling still looked stunning. Her blonde hair was meticulously managed, her makeup expertly applied to give the casual observer the impression she was wearing none. Only when viewing her side profile could one clearly see her pending maternity; no fat cells had dared invade other parts of her body, or if they did, they hid in terror from whatever workout regimen even this severely pregnant host imposed on them.

She was the kind of woman who had the ability to get most men to do most of whatever she wanted. I ought to know: she got me to marry her. To this day, Andrea continues to characterize the relationship between my ex-wife and I as a hostage taking; I was simply Sandi’s first long-term victim, the divorce settlement my ransom. I continue to plead temporary insanity.

For most people, divorce generally means having little or no contact with the former spouse. At the very least, the amount of contact ought to be less than prior to the marriage’s dissolution. Several months earlier, however, Sandi had revealed to me her pending maternity in all its gloried detail save one: the identity of the father. That she continued to shield the father from me made clear it was a moment she was not proud of. It did give me some small satisfaction that at least I was better than the man who had unceremoniously knocked up my stuck-up ex. It wasn’t enough satisfaction, however, for me to be pleased to see her at my apartment. “The cheque’s in the mail,” I told her as I approached.

“Funny. Like you’d have any money to send me even if I did need it,” she replied. I had created that opening myself: Sandi could never resist reminding me of the cut in pay I had taken in my change of vocation. At least in my previous employment the potential was there to earn the kind of income needed to live in the wealthy enclave of Point Grey. On my teacher’s salary, I would be lucky if I could pay to have my car towed away from said enclave. Good thing I’d been living largely off Sandi’s wealth the whole time we were married.

Despite Sandi’s insistence on remaining a part of my life — we would always be really good friends, she kept assuring me — I never looked forward to her always unannounced visits. Of course, if her visits were announced in advance, she had long since figured out I wouldn’t be home when she arrived. Sandi stepped aside as I reached the doorway and followed me in as I unlocked the door. I didn’t bother trying to stop her; it would only make whatever argument we were about to have that much more public.

“I see you’ve been redecorating,” she said, pointing to the white splotches of paint that covered the previously graffiti-covered door. “Chic. It goes with the general green tarpaulin look your condo’s been sporting.”

“So what can I do for you?” I asked after closing the door and heading up the entrance hallway. “Are you just here to comment on my surroundings, or did you need to mess with my psyche as well?”

“Winston, that’s not fair. I haven’t talked to you in ages. I wanted to see how you were doing.” Sandi wanting to know how I was doing was always a euphemism for her wanting to know how I could help her in some way.

“Wine?” I asked.

“Have you finally bought some non-alcoholic for me?”

“And let that swill enter my home? Perish the thought.”

“I don’t know what happened to you, Win. You’ve become such a snob.” She was right, and I had a pretty good theory about how I’d gotten there, but I was just too tired to trade insults with the former love of my life. Andrea always told me it’s because I couldn’t win in a war of words with Sandi. “I was hoping we could talk.” Uh-oh.

“Talk about what?” I could do little to hide the suspicion in my voice. My heart rate only heightened as Sandi took up residence on the couch with both feet planted firmly on the floor in front of her. If this had been a casual visit, she would kick off her shoes and tuck her legs up onto the couch beside her, even though the move would be awkward in her pregnant state. Feet on the floor in front of her never led to anything good.

“Relax. You look like you’ve seen a ghost.”

“You’re pale, but ghostly is a stretch.” She sighed her pouty sigh, the one that indicated she was disappointed with the attitude I was taking. I had heard that sigh a lot at the tail end of our marriage; it had pretty much been the cornerstone of our communication. “I’m sorry,” I told her. “I’ve had a hard week. You were saying?”

“I know that things haven’t always been really good between us. But you know that I still love you and consider you to be one of my closest friends?” See?

I believed the question to be rhetorical, so I didn’t respond. I always found it disappointing when someone didn’t recognize one of my own rhetorical queries and made a generally lame attempt to answer it. Besides, the only thing I could think of was a snide comment about her needing to get some new friends if she considered me to be one of her closest confidantes. But judging from the tone of her voice, whatever was coming next was sensitive enough that I ought to at least try to appear empathetic. “So I need to ask you something very important.”

“Okay.”

“Win, I want you to be there when the time comes.” She spoke so softly and with more humility than I’d ever heard from her that I momentarily forgot about her impending maternity and didn’t follow what she was talking about.

“Be where?” Her eyes widened in astonishment. That happens a lot to me with women, it seems. In her surprise she leaned backwards on the sofa, and her distended belly protruded into my line of vision. “Oh,” I said, nodding and sounding a lot, I supposed, like Edith Bunker. The silence returned for a moment. Truthfully, it wasn’t that I didn’t want to support my ex-wife in her moment of need; to my own constant consternation, deep down on some twisted level, I still cared about her, much as I frequently couldn’t stand her. The sad fact of the matter was that I found the whole idea of being in the delivery room kind of gross. I knew that wasn’t likely to go over well as an excuse to get out of the role of Lamaze coach.

“Well?” she finally asked.

“Sandi, I don’t know what to say.” It was one of the few times in recent memory that I wasn’t lying to her. How the hell do you tell your ex-wife you’d rather be any other place than watching her give birth to some unknown man’s bastard love-child?

“It’s easy, Win,” she said, leaning as far forward as her pending addition would permit. “You just have to say yes.”

She was probably right; I could think of no way I could get out of this without some extremely clever excuse I could not concoct on the spot. Wine. I needed wine. Sandi continued to eye me, waiting for me to capitulate. With shocking clarity, I was beginning to realize I was about to agree to watch the whole birthing blood sport that would be Sandi’s spawn’s arrival. Too stunned to speak, I had only just begun to nod my assent when both our attentions were diverted to the sound of a key in the front door.

“You’re really going to love me,” I heard Andrea already beginning before even coming into view. For all she knew I could be sitting on the toilet, but she would simply stand outside the bathroom door and let loose whatever was on her mind. “Not only am I the greatest crime fighter in the history of the city, I brought dinner. And I don’t want to hear any complaints about my choice of … oh. You’re here.” Andy had made her way into the living room mere seconds before I was about to commit to my new role of midwife to the ex-wife.

“Andrea,” Sandi said, making no attempt to hide her disappointment not only at being interrupted but being interrupted by Andy, a woman of whom she had never grown fond. There are people whose outward contempt for one another often masks a deep-rooted respect and admiration for the other party. That was not the case here. They truly couldn’t stand one another. In deference to me, they were civil when the planets aligned to put the three of us in the same room, though I would have liked to see the two of them settle their differences with a good old fashioned mud wrestle — or at least a pillow fight. About the only thing these two headstrong women could agree on was their mutual need to chastise me for the way I ate, looked, dressed, worked, etc. The only way it could get worse would be if my mother joined them in the room.

“I didn’t realize you were having company,” Andy said.

“I didn’t either.”

“Winston and I had something very important to talk about.” If Sandi thought her not-so-subtle hint would cause Andrea to leave, she had temporarily forgotten who she was dealing with. Andrea does not like me to be alone with my ex-wife. She thinks I’ll do something stupid. Like get her pregnant. “Winston is going to be there for the delivery.”

Andrea nearly dropped the extremely large pizza box onto my birch floor. “Him?” she asked.

“Yes. We may not be married any more, but we’re still very close.”

“We are?” I asked. Both Sandi and Andy looked to me for clarification. “I mean, you know, you asked me, but I didn’t realize I had responded in the affirmative.”

“You did.”

“I did?”

“Yes Winston. Don’t deny it. You can’t back out now just because you’ve got backup. I’m counting on you to be there for me.” She stood up. “Just like I’ve been there for you all these years.” That statement was even more ludicrous than the notion of me in a delivery room, but I was too stunned to argue.

“But this is Winston,” Andrea interjected. “He cries if he has to squish a spider, for god’s sake.”

“That’s not true.”

“Right. That would presume you could get close enough to a spider to do the squishing.”

“Exactly.”

“None of that matters,” Sandi insisted as she put on her coat. “I know that when I need him, Winston will be there, strong and ready to support me in this most important moment. I can count on him. You should have more faith in your friend.”

“Right,” Andy replied. Sandi left in a huff, which was the way she made most of her exits. Andy continued to smile her Cheshire Cat grin, always pleased at having caused Sandi to leave a room, as she carried her takeout victuals to the small tiled area that passed for my kitchen. “Come and eat,” she commanded. She reached absentmindedly for two wine glasses and helped herself to a bottle from the rack.

“Cabernet?” I scoffed. “With pizza?” She slid it back into the rack.

“You would suggest?”

“Something gentler, like a Pinot Noir. One mustn’t overwhelm the palate with so bold a beverage without a meal of deeper substance.”

“You’re such a dork.”

“It’s true.” Andy ignored my sommelier instincts and pulled out the Cabernet.

“So who’s the world’s best detective?” she asked.

“Sherlock Holmes.”

“I meant living and non-fictional, though if I were fiction, I’m sure I’d be in the same category as Holmes.”

“I would have put you closer to Clouseau.”

“Certainly you should remember I’m about to crack your case wide open before you go insulting me.”

“‘Crack the case?’ Wow. Talk about shock and awe.”

“I’m about to tell you of my major crime-solving finesse, and you’re busy snobbing me out about my wine selection.”

“You simply cannot expect me to take you seriously if you plan to use ‘snob’ as a verb.”

“Gerunds offend you now?”

“A gerund is the other way around. You were saying about cases being shucked?”

“Cracked. We found something at the crime scene.”

“What?”

“Prints. Better yet, prints in our system.”

“They left their prints on the goalpost?”

“Not that crime scene. This one.”

“You CSI’d my place?” Andrea frowned at my pop culture reference; she watched just as much TV as me, but it bothered her when I felt I knew something about her job based on what I’d seen on the box. “Why would they have touched the door?”

“They didn’t. They did, however, dump their spray paint cans into the bushes in your back alley.”

“You are thorough.”

“Clouseau be damned.”

“But how do you know those are the paint cans used to badly misspell homophobic graffiti?” Instead of answering, Andy, whose mouth was full of the gigantic pizza slice she had extracted from the box without benefit of utensil, plate, or napkin, pointed at her midsection, a gesture she normally used to remind me she had abs of steel, but which this time was intended to demonstrate she had solved the great graffiti caper through her infallible gut instinct. “Oh well, at least there are sound scientific principles involved.”

“Prints were left on the cans.”

“So you said. But that makes no sense. Those were definitely kids in the hallway. If they’re young offenders, why were their prints in the system?”

“They weren’t. We found the prints of a twenty-eight year old ex-con who did time in the late nineties for drug trafficking.”

“And?”

“And we got lucky. He works in a hardware store not six blocks from here.”

“How is that going to help us?”

“How many cans of spray paint do you think he sells to teenagers in this neighbourhood?”

“Sounds like a bit of a long shot to me. How do you know these paint cans were the ones sold to our graphic artists?”

“Oh, they were,” she replied, pointing again to her midsection. “Now all we have to do is take in your school’s yearbook and have our paint-meister pick out your perps from the photo array, as it were.”

“It’s my first year teaching, and the year isn’t over. I don’t have a yearbook.”

“I picked up last year’s from your school library on my way here.”

“Thorough,” I admitted again. She tsk’d me as she crammed the rest of the pizza slice into her mouth.

Home Depot is the kind of big box store that brings out the protestors when it moves into town, perhaps not as virulently as those picketing a Walmart opening, but vocal just the same. Vancouverites as a rule love a good — or even a piddly — protest, and no matter how few picketers arrive, it’s sure to make lead coverage on at least one of the nightly newscasts. Lazy journalism to be sure, but it’s mildly more compelling than the oft featured weather piece.

Despite protests, sit-ins, and bullhorns, the “tight-knit” Kitsilano community, home to some thirty thousand best friends, has now a Home Depot to call its own, albeit a “greenerized,” slightly smaller version of its suburban counterparts, and on this Friday evening, it was jam-packed, not with demonstrators but with consumers. Having satiated their need to rail against it, tight-knit community members were evidently inducting the corporation into the community by spending thousands of dollars on its wares. There’s already talk of a second one.

Andrea walked purposefully through the doors, though I knew full well her ability to tell a lathe from a drill press was about as strong as my knowledge of what either a lathe or drill press were. Her mission senses were heightened, though, and thus she practically scented her way to the paint department and made a beeline for the clerk operating a machine that was treating a can of paint like it was mixing a gallon of martinis. I recognized him from the dated mug shot Andrea had shown me on the way over. He had gained a few years and a few dozen pounds — the paint shaking business had obviously been good to him — but there was no mistaking this was our guy. “Courtney MacMillan?” Andrea asked in her polite but unmistakably police-like tone.

“I’ll be right with you,” he replied politely.

Andrea flashed her badge at him. “No, you’ll be with us now.”

“Okay,” he replied calmly. If Andy’s badge routine had upset him at all, he gave no indication. I would have been offended at her brusque intrusion, but MacMillan calmly reached up, turned off the paint can shaker-upper and handed the mixed latex cocktail to his waiting customer, who herself looked taken aback by the sudden appearance of the long arm of the law. Andy looked as though she was ready to begin when MacMillan politely spoke first.

“If you wouldn’t mind, could we converse in the back, away from the customers?” He turned, stepping out from behind his paint partition, and walked toward the back of the store.

“Converse?” I said to Andy as we fell into step a few paces behind the departing paint-smith. She managed a sort of perturbed “harrumph.”

“Boy, he didn’t seem to be the slightest bit intimidated by your bad cop bit. Maybe you want to switch to good cop?”

This time she managed a brief retort. “We’ll see.”

MacMillan stopped at the entrance to a hallway marked “Private, Staff Only.” Turning to face us as we approached, he gracefully waved us down the hallway ahead of him. “This way,” he directed serenely, “if you would not mind.”

“We would not mind at all,” Andy assured him.

“Thank you, Detective,” MacMillan replied. He stepped in front of us to hold open the swinging door to the inner sanctum of the home improvement mecca. He allowed the door to gently close behind him, then, without further word, strode down the nearest aisle way between two large shelving units. As he turned to face us his eyes blazed with rage. “Just who the fuck do you think you are, lady?” he hissed.

A slight smile pulled at the left corner of Andrea’s mouth. “I’m sorry,” she said, her voice adopting the same placid tone MacMillan’s had just seconds before. “I could have sworn I identified myself when I came in.”

“Can the bullshit. You’ve got a lot of fucking nerve barging in to my place of work and harassing me like a fucking criminal.” It was clear MacMillan’s Mr. Manners routine had been an act to save face in front of the customers. Or he was a sociopath; it’s hard to tell the difference sometimes between a good actor and a psycho. His diction, I noted, remained impeccable, clearly articulating the “ing” of his expletives rather than the more colloquial “in’” most often used in today’s vernacular.

“Aren’t you?” Andrea asked.

“I was.”

“I stand corrected.”

“So what the fuck do you want?” His face was reddening, and he was growing increasingly agitated by Andrea’s sarcastic grace.

“I want some information. I’d like your help.”

“Why would I help you?” He had a point.

“Because you want to be a good, decent citizen, and you don’t want your parole revoked.”

“Okay. What do you want?” he sighed.

Andrea pulled out the school yearbook from the oversized, low budget purse-cum-briefcase she kept in the car but rarely carried. “I want you to find someone for me. A few days ago you sold some spray paint.”

“We’re a big store. How do you know it was me that sold the paint?”

“Your prints were on the cans.”

“Did it occur to you that if I stocked the shelves, my prints would be on every can?” It hadn’t occurred to me, but I had to imagine it had to Andrea the super-cop. If it hadn’t, she wasn’t about to admit it.

“Humour me,” she said. Reluctantly he took the yearbook from her and made a half-hearted effort to flip through some pages and skim the photos. “Does this mean you remember selling to some teenagers recently?”

He didn’t answer but continued to turn pages and scan images. After several minutes of silence, during which I counted eight different brands of bathroom sinks, MacMillan turned the book around to face Andrea. His finger pointed to a Grade Eleven student — this year in Grade Twelve — named Paul Charters. He was in my Law 12 class. Andrea didn’t speak but took out her police notebook and recorded the name. The department had issued its detectives handheld personal digital assistants, but Andy had told me that powering up the BlackBerry lacked the dramatic flair of the flipped-open notebook.

A moment later he turned the book again and pointed at another student, Krista Ellory. It hadn’t struck me that any of my hallway redecorators might be female. My sexist upbringing, I suppose, had taught me that homophobia was essentially a male affliction. “Yes, I’m sure,” MacMillan answered before being asked.

“So you remembered selling the paint all along,” Andrea noted.

“You don’t sell a lot of spray paint to teenaged girls. It’s easy to remember.”

“See how we could have avoided all this unpleasantness if you’d just cooperated in the first place?”

“Probably would have gotten your information faster if you’d been a whole lot more polite and less aggressive.” That, of course, was my whole point all along. Andrea uncharacteristically made no response, smart-assed or otherwise. She made a few more notations on her little pad, which I recognized as the detective equivalent of counting to ten. Finally she asked, “Do you recall if they said anything about their plans for the paint?”

“Do you mean did they confess any nefarious intent to this complete stranger of a paint clerk? As I recollect, they proffered no such information.”

Nefarious? Three more syllables than “bad.”

“And can you tell me on what day they bought the paint?”

“No.”

“No?”

“No. I recall recently selling paint to those two kids. On what day the transaction transpired I could not say.”

His politeness was clearly — at least to me — starting to rankle Andrea. It was amusing to see her starting to frazzle the more polite and articulate MacMillan became. Rather than risk further confrontation, she opted to terminate the interview. “Thank you. We’ll be in touch.” With that she turned and headed for the door. I smiled as warmly as I could at MacMillan then hurried after my friend.

“So what now?” I asked when I met her pace. “Do you go roust the perps?”

“Tomorrow. I’m tired of crime busting for the night.”

“All right. It’s been a long week. You can drop me off at home and I’ll begin my reward-less ritual of trying to sleep.” Andy shot me a sideways glance. “What?” I asked, stepping out into the environmentally friendly, SUV-filled parking lot.

“I’m not going home.”

“Ooh,” I groaned. “Do we have a hot date I’m just now being made aware of?” As a rule we were both so hopelessly inept at affairs of the heart, we tended to pre-brief one another about prospective and upcoming romantic engagements, followed by an in-depth de-brief, usually the same night. If the de-brief couldn’t take place until the next morning, it was considered unnecessary.

“Hardly,” Andy replied coolly. “I’ll be staying with a sick friend, remember?”

“Who’s that?” She shot me another sideways glance. “I’m not sick.”

“That’s debatable.”

“Is this because you feel a need to protect my front door from further anti-homosexual vitriol?”

“And/or you from the same type of anti-gay beating delivered to your little law protégé.”

“I’m pretty sure I’ll be all right.”

“Because you’re so tough? Masculine? Straight?”

“Because I’ll be in my apartment, locked from the hallway and the outside.”

“That doesn’t fill me with a great deal of confidence, given how effective security has been at your place in the past.”

“We’re not dealing with the same caliber of skels.”

She shot me another look across the roof of her unmarked police cruiser as she unlocked the door. “You must stop watching NYPD Blue re-runs. You need a life.” No argument there, though I’ll give up Sipowicz around the same time I give up red wine.

“Still. I don’t need a bodyguard. I’m sure the people who beat up Tim have no desire to beat me.”

“Your door was their first target. And few people need much of a reason to want to beat you. I think of it almost daily. Besides, I’m not doing this for your sake. If someone gets their hands on you again, your mother will never leave me alone.” She had a point. A few days of living with me until she made an arrest would be much less torturous than a guilt-riddled conversation with my mother. We rode a few blocks in silence, thinking about Tim and the two students who had been identified by MacMillan. Finally I couldn’t resist commenting on Andy’s interviewing technique.

“Have you ever heard the expression you catch more bees with honey?”

“Shut the hell up.”

“Indeed.”