Читать книгу When the World Outlawed War - David Swanson - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

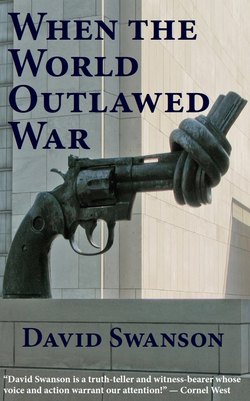

THE OUTLAWRY OF WAR

ОглавлениеOne organization which happens to have far outstripped that volume of literature distribution deserves particular attention, although it was largely a front for a single individual and largely funded out of his own pocket. The American Committee for the Outlawry of War was the creation of Salmon Oliver Levinson. Its agenda originally attracted those advocates of peace who opposed U.S. entry into the League of Nations and international alliances. But its agenda of outlawing war eventually attracted the support of the entire peace movement when the Kellogg-Briand Pact became the unifying focus that had been missing.

William James’ influence could be seen in Levinson’s thinking. Levinson also collaborated closely with the philosopher John Dewey, whom James had greatly influenced, as well as with Charles Clayton Morrison, editor of The Christian Century, and with Senator William Borah of Idaho, who would become Chair of the Committee on Foreign Relations just when he was needed there. Dewey had supported World War I and been criticized for it by Randolphe Bourne and Jane Addams, among others. Addams would also work with Levinson on Outlawry; they were both based in Chicago. It was the experience of World War I that brought Dewey around. Following the war, Dewey promoted peace education in schools and publicly lobbied for Outlawry. Dewey wrote this of Levinson:

There was stimulus — indeed, there was a kind of inspiration — in coming in contact with his abounding energy, which surpassed that of any single person I have ever known.

John Chalmers Vinson, in his 1957 book, William E. Borah and the Outlawry of War, refers to Levinson repeatedly as “the ubiquitous Levinson.” Levinson’s mission was to make war illegal. And under the influence of Borah and others he came to believe that the effective outlawing of war would require outlawing all war, not only without distinction between aggressive and defensive war, but also without distinction between aggressive war and war sanctioned by an international league as punishment for an aggressor nation. Levinson wrote,

Suppose this same distinction had been urged when the institution of duelling [sic] was outlawed. . . . Suppose it had then been urged that only ‘aggressive duelling’ should be outlawed and that ‘defensive duelling’ be left intact. . . . Such a suggestion relative to duelling would have been silly, but the analogy is perfectly sound. What we did was to outlaw the institution of duelling, a method theretofore recognized by law for the settlement of disputes of so-called honor.

I’ve lifted this quote from John E. Stoner’s 1943 account, S. O. Levinson and the Pact of Paris: A Study in the Techniques of Influence, a book looking back at the lessons of the 1920s peace movement even as world war raged again. Quincy Wright claims in the introduction that “it is safe to say that if Levinson had not moved the isolationist Middle West and the isolationist Senator Borah to support the Pact, it would not have been achieved.”

Levinson wanted everyone to recognize war as an institution, as a tool that had been given acceptability and respectability as a means of settling disputes. He wanted international disputes to be settled in a court of law, and the institution of war to be rejected just as slavery had been.

Levinson understood this as leaving in place the right to self-defense but eliminating the need for the very concept of war. National self-defense would be the equivalent of killing an assailant in personal self-defense. Such personal self-defense, he noted, was no longer called “duelling.” But Levinson did not envision killing a war-making nation. Rather he proposed five responses to the launching of an attack: the appeal to good faith, the pressure of public opinion, the nonrecognition of gains, the use of force to punish individual war makers, and the use of any means including force to halt the attack.

Levinson would eventually urge the nations signing the Kellogg-Briand Pact (also known as the Pact of Paris) to incorporate the following into their criminal codes: “Any person, or persons, who shall advocate orally or in writing, or cause the publication of any printed matter which shall advocate the use of war between nations, in violation of the terms of the Pact of Paris, with the intent of causing war between or among nations , shall be guilty of a felony and upon conviction thereof shall be imprisoned not less than ______ years.” This idea can be found in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights of 1966, which states: “Any propaganda for war shall be prohibited by law.” It was an idea that also influenced the Nuremberg prosecutions. It may be an idea worthy of revival and realization.

Kirby Page, another Outlawrist, in The Abolition of War (1924) distinguished war from “police force,” meaning law enforcement by domestic police. Police force, he wrote, involves a neutral third party bringing a suspect to a court for application of the rule of law, while, in contrast, a war is judge, jury, and executioner all in one and corrupted by the passion of violence. In addition, police go after only suspected criminals, whereas a war goes after a criminal and his wife and kids and neighbors, setting in motion a process that will also likely kill family members and friends of the war makers.

In 1925 Page published An American Peace Policy in which he argued for the world’s interdependence, the League, the World Court, and Outlawry. In arguing against the use of force to sanction a nation for its use of force, Page pointed to the failure of such a proposal in James Madison’s original Virginia Plan. The U.S. Constitution does not, in fact, sanction the Union to employ force against a state (although it in fact did so against several in the Civil War). Page quotes James Brown Scott on James Madison thus:

The more he reflected on the use of force, the more he doubted the practicability, the justice and the efficacy of it when applied to people collectively, and not individually. A union of the States containing such an ingredient seemed to provide for its own destruction. The use of force against a State, would seem more like a declaration of war, than an infliction of punishment, and would probably be considered by the party attacked as a dissolution of all previous compacts by which it might be bound.

Salmon Oliver Levinson