Читать книгу Beep - David Wanczyk - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

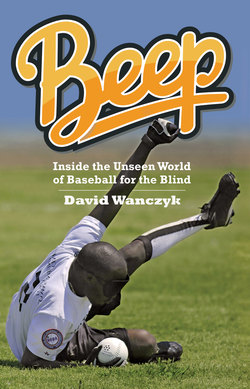

ОглавлениеTWO

The Rookies

The pleasure of rooting for Goliath is that you can expect to win.The pleasure of rooting for David is that, while you don’t know what to expect, you stand at least a chance of being inspired.

—Michael Lewis, Moneyball

AT 8:40 A.M. on the muggy opening day of the 2013 Series—eons before the intense international final—a pair of guide dogs panted under an oak tree and the Athens Timberwolves couldn’t find their hats. It was their first World Series, and they could be forgiven for feeling flustered. Still, this is the day even the hatless twentieth seed in a twenty-team tournament thinks it has, in the words of Chicago Comet Mike “Hoodlum” McGloshan, “that magic shit to win it.”

I had arranged to fill in as an emergency backup with the long-shot Wolves, and I felt that magic, too. By rule, if a team can’t field a full contingent of six blind players, the coach can substitute two blindfolded sighted folks, so I pitched in $32 for some last-second hats at the merchandise tent, and we all hustled—deliberately—to the field. This was their debut game, mine too, and we found ourselves across the diamond from Taiwan Homerun.

The guys in light blue were at the field an hour before the game, taking batting practice. A group of fans laid out an extensive buffet for them while Rock Kuo and Fernando Chang smacked the ball wherever they wanted it to go. As the Timberwolves caught their breath, Taiwan showed off in the field by catching beep balls on one hop. No one in the league had heard anything yet about Taiwan’s new player, Ching-kai Chen, number 9, but he was the main magic man, squatting while he made the improbable plays, his knees turned in slightly like a hockey goalie covering the five-hole.

Athens, on the other hand, didn’t make contact during their rushed BP. They also had a couple of guys who already looked like they needed a hot soak, including their most seasoned player, sixty-seven-year-old Roger Keeney.

“I’m all for positive thinking, but Taiwan is going to kick our butt,” said Amanda Rush, wearing a blue bandanna and smoking luxuriously. “And then they’ll say, ‘Good game. Oh yes. Next year, you have team?’”

Essentially, Athens was bare-bones: the minimum six players, the minimum contingent of volunteers, and me. I was already languishing in Georgia’s morning heat, and a good half of the T-wolves were faring even worse. Their sweat-and-swoon became a moral problem for me when I found myself wishing for one of them to falter so I could get in a game. Then, as I did some perfunctory stretching, Roger told me that I wasn’t registered with the team and would likely be barred from playing.

One of the things that had sealed the deal for me to head down to Georgia, a sixteen-hour drive from my place in Ohio, was Roger’s suggestion that I might be able to sub for his team. This chance was worth leaving my wife home alone with our six-month-old daughter for more than a week. Because how could I describe the danger and excitement of beep ball, I told myself, if I’d never gotten one hit at my face? As eighteen other teams began their World Series dreams, I sulked. My hat didn’t fit and I wanted my $32 back.

At 9, we heard a reveille of buzzing bases as officials at all the fields tested the equipment. The entire battalion of beep baseball was on the move. Austin advanced on the St. Louis Firing Squad; Boston marched on Tyler, Texas; the Indy Thunder faced off with the New Jersey Lightning. Nine beep balls began their insistent whining, but I was left behind. I’d been so close to the unorthodox sports story—go-getter reporter abandons wife, baby, and most important sense to try bizarrely challenging sport—but now I was just a guy getting a sunburn on a Tuesday morning.

Taiwan got up on Athens 11–0 in as pedestrian a way as possible. Topspin ground balls, misplays in no-man’s-land. Athens didn’t have the aggressiveness to cover the whole field, and Homerun’s speed blew them away. Rock Kuo, a college administrator with seriously blurred vision and a seriously high leg kick as he swings, led off and fouled the first pitch back, bursting out of the box, but when he realized the ball wasn’t in play, he stopped short and a volunteer led him, by the bat, back to the plate. To reorient himself, Rock knelt down, laid his bat against one of the plate’s edges, and touched its points. He easily scored on his next swing.

Then came Ching-kai Chen, making his debut. Chen had garnered great interest at home in Taiwan after appearing in a commercial with a pop star for the Institute for the Blind of Taiwan. In the commercial, Chen serves the singer a cup of coffee and moves so fluidly that an audience might not notice his impairment. Chen promptly poked one to right, reaching first base and scoring. He had a memorable day all around, going 5 for 5 against Athens, eventually scoring on his first nine World Series plate appearances, and registering ten putouts in the field. Veteran athletes across the league, hearing tall tales of his performance, suggested to each other that if he was for real they might as well hang up their blindfolds.

“Man, when you’re playing Taiwan, you cannot take your sweet time,” Athens infielder Jonathan Pichardo said. “We got a long way to go.”

The Taiwan beep baseball program had been in that long-way-to-go place in the late nineties. The Taiwanese-American sponsor of the team, James Gong, told me that he’d heard back then that it takes seven years to get a good beep ball team up and running, and in fact, seven years into their own experiment, in 2004, Taiwan won their first World Series. Gong said Athens should be patient.

“The only difference between people is how serious they are,” Gong said. “‘Oriental’? They’re not smarter. They treat everything much more seriously.”

That seriousness had been clear even at the tournament’s opening ceremonies. For the first time, the series began with a non-baseball event—a blind kayak race with a grand prize of $5,000 put up by a local BBQ joint. On the rapids of the Chattahoochee River, each blind paddler was guided by a sighted coxswain, and just as in the main event there were two teams that stood above the rest: Taiwan and Austin.

With the Foreigner song “Double Vision” playing over the loudspeakers, the Taiwanese team moved on the river like an ambulance through a traffic jam. Other kayaks veered aimlessly, rolling with the tide toward Phenix City, Alabama, on the opposite bank. Boston’s Joe McCormick spilled into the river.

Homerun had been practicing kayaking for weeks. This distinguished them from every other team, and was sort of like a father-and-son pair running daily drills in advance of the county fair sack race.

“Taiwan with a commanding lead now,” the master of ceremonies declared over the PA. “The Athens Timberwolves? I’m trying to get a read on them. They are barely past the start line.”

Meanwhile, Austin showed some kayaking talent of their own, as Mike Finn, a personal trainer, paddled at a steady pace in his opening heat.

“We set the bar right here-ah,” Lupe Perez shouted to the river. “We’re looking for redemption,” he said. But with the kayak money on the line, things weren’t close. Even though some competitions are meant to test what we can do off the cuff, Taiwan Homerun doesn’t do off the cuff, and as their kayak floated toward an easy victory over Austin, the Taiwan fans—expats from Atlanta mostly—sprinted down the riverwalk chanting, “Go, Taiwan, go.”

“The only thing in their head is winning,” James Gong told me.

• • •

The opening-round game between Taiwan and Athens on the first day of the tournament was not actually about seriousness, though. Instead, it featured some major athletic discrepancies that highlighted the fact that beep baseball is played on two different levels: major league and rec league. But Athens did have some bright spots in their opener. Keeney scored the first run in the team’s tournament history—“The old man still has it,” he yelled. It was a run that had him aching for the rest of the day. In the field, Ron Whorley was a standout. He’d been blinded a long time ago in an accident involving nails, his sons told me, a fact that seemed too painful for a follow-up question. We watched him, impressed, as he recorded a bunch of acrobatic putouts in left field.

But Athens limped to the finish against Taiwan, putting only five balls in play. Scean Atkinson, an infielder who usually has the confidence and voice of a shock jock, struck out three times, chopping down awkwardly at the ball. And while it’s easier to have an “it’s just a game” feeling when you lose in beep ball, most of the players don’t want that feeling. Athens (0–3 on the first day of round-robin play), Boston (2–1), Indy (also 2–1), and Austin (3–0, easily) weren’t looking for moral victories. Blind people have mostly had their fill of that sort of thing, of being told how courageous they are just to be out there. Instead, they all took the field knowing that they had the emancipating opportunity to simply compete, and Athens got a faceful of that freedom on day one. The final score against Taiwan was 19–2.

My personal solace came when one of the Athens volunteers penciled in my name on the T-wolves’ roster while some official-seeming officials—clipboards, lanyards—weren’t looking. Due to that deft bit of corruption, I became an eligible emergency replacement, a kindly vulture circling my new blind buddies and half hoping that one of them—maybe the shortstop nicknamed Cupcake, the old man?—would fake a hip flexor and give me a chance to play.

After the Taiwan drubbing, I wandered away from the Athens bench to catch some other games. The Minnesota Millers and the Iowa Reapers had a fraternal rivalry, Steve Guerra vs. Frank Guerra, that I wanted to check out. The twins, both of whom had congenital cataracts and lost their sight in the early seventies after bungled operations, are the Click and Clack of the NBBA. During their game, Steve jokingly threatened an ump who’d ruled against his team. “You can’t run,” he shouted to the ump, and Frank retorted, “But you can’t find him.”

Both Guerra brothers used to play for the Long Island Bombers—Frank sported a Bombers tattoo on his chest—but their jobs took them to the Midwest. All of this—sight loss, the heartland, brotherhood—including the detail that Frank was born two minutes earlier and therefore believes his brother to be “overcooked”—seemed like it had the makings of a good-natured Reader’s Digest story to me, but before I could come up with any of my own “Humor in Uniform” jokes, I got the call-up.

Athens infielder Tamara Hale (Cupcake!) had tweaked her leg—wink?—and my team needed me against the Long Island Bombers. I hadn’t played baseball in years, but I thought I might be an improvement over an injured young blind lady. I sprinted from field to field. Maybe if I made some good plays they’d nickname me “Sheetcake.” In my fantasy, I became crack third baseman and clutch hitter:

I gallop into the gap and dive for the beep ball, tipping it expertly to Ron Whorley in an act of athleticism unmatched in the annals of sighted–blind cooperation. At the plate, I call my shot, Babe Ruth style, even though I’m not entirely sure where I’m pointing. This is understood by teammate and opponent alike as an act of great gumption, and I rocket the first pitch deep to center, hitting it with such force that the ball emits, instead of its normal beeping, an instrumental version of Tina Turner’s “Simply the Best.”

Cries of “Sheetcake, Sheetcake” reverberate across the Peach State. The art of Braille, I find, isn’t hard to master, and the gathered guide dogs consider me a most firm alpha male. My facial hair becomes a league-wide style, and later, against Taiwan in the final, I scoop up the series clincher while declaring in Mandarin, “Fine effort, fellows, but all for naught.”

When an Athens volunteer covered my eyes with a spare piece of ripped cloth the Timberwolves had in their bat bag, though, my Walter Mittyish bravado disappeared. The anticipation to rush out on the field was replaced by a deep desire to find a fence, get my back up against it, and stay put until someone handed me a sandwich. Whorley, the Athens left fielder, informed me that while I was blindfolded I would feel like I’d moved forty feet while only moving four, but knowing that in advance was not like experiencing it. I took six steps and thought I was in my correct position on the field, but then I hit my shin on the Athens bench, overturning our water jug.

At bat, I knelt down to align myself, touched the plate four times like I’d seen Rock Kuo do, pointed to the pitcher’s voice, and swung hard at the void. I struck out. In my next plate appearance, Ben, Ron’s son and the Athens pitcher, set me up well and I dribbled one to the infield somewhere. Third base buzzed, so I was supposed to run, unnaturally, toward the sound on my left. Except that’s the way the beep ball rolled too. Confused by the dueling noises, I hopped twice and ran in the opposite direction before realizing my mistake and booking for third. My wife tells me I have the sense of direction of a squirrel crossing the street, and it was certainly true during that at-bat. My arms were everywhere as I crossed close to the pitcher’s mound, nearly trampling the Bombers’ charging third baseman, who was unaware that I was barreling toward him like a disoriented Pete Rose at a defenseless Ray Fosse. The umpire yelled “Stop!,” preventing our head-on collision, and my main athletic feat of the game was the restraint I showed in not breaking an opponent’s nose with my knee.

I was out. I went 0 for 4 in the game, with three strikeouts.

In the field, I fared a little better. Out of generosity or out of respect for my noteworthy wingspan, the Athens coaches put me at third base, the busiest beep ball position. Once there, I entered into an ongoing call-and-response with Scean and Ron.

“Scean, not sure if I’m right.”

“You’re good.”

“Ron?” I said pleadingly, as if I’d begun to fear he’d somehow disappeared in the middle of the inning.

“Yep.”

Ron was my on-field compass, and by the fourth I felt more comfortable, but he’d just had a shock himself and needed some grounding. During our at-bat, he’d laced a ball right up the middle and struck his son, the pitcher, in the temple. Upon contact, Ron raced for the first-base bag, finding out moments later that Ben was crumpled on the ground. Pitchers are a brave lot, and Ben is no exception. They stand close to the plate and serve up meatballs to some pretty burly folks. Kevin Sibson of Austin gets pegged every practice, and Tim Hibner, a journeyman pitcher from Oklahoma City, actually likes getting hit because it means he’s timing his pitch correctly.

Usually, a beep ball to the crotch is the worst-case scenario, but some have been knocked out by frozen ropes to the heart, and at least one pitcher has spat teeth.

Ben got up after three minutes, we all gave the requisite applause for a sports injury, and Ron, who’d been retired on the play, had to run out to the field again. When he came back to the bench after that half inning, Ron whispered to me, “Where’s Ben? Let me get to Ben.” I stood up and Ron slid over to his woozy son. He threw an arm around him, called him “boy,” and felt for his bruise.

• • •

With concussion fears behind us, Ron dispensed more of his wisdom. He’d recognized from the distance of my voice that I was a step, or six steps, out of place. Scean, too, directed me toward the baseline or away from it as I called out, “Ron, Scean, am I good?”

“That beep,” Scean said. “You chase that beep and when you find it, you feel like you achieve something.” He roamed the field. He had some of his swagger back after recording a putout; I didn’t. I still felt like a three-year-old asking for the hall light to be left on.

We called out our positions in the field, around the horn. “Where are you, Timberwolves?” Keeney shouted, adding his “one” from first base. “Two,” said Jonathan, at second. Scean yelled “three,” and I put everything I had into my “four.” Ron and Amanda chimed in with five and six. It was a simple sound-off to let each other know we were still together.

Swelling with team pride and thigh sweat, I tried hard to act natural. Wearing the blindfold made me feel languid, though, and I noticed that sightlessness, even if it’s just an experiment, gets a guy to limit his unnecessary movements. I imagine I resembled an upright corpse, but I also tilted my head to the left, maybe to hear better out of my right ear and maybe from darkness-induced exhaustion, so I probably looked more like an upright zombie.

“Ron, Scean. Am I undead?”

From there, I crouched into a third baseman’s posture: knees bent, head tilted, totally ready to get in front of something I’d never see coming. It occurred to me—things occurred to me a lot while I couldn’t see—that there was something metaphorical about being a blind third baseman. Stuff can pass by without you knowing it, or surprise you and hit you in the throat. But if I acted ready, hands in front, maybe I’d be ready.

During the game against Long Island, I had six hit my way, and I fielded three of them before the batter scored. Once I stopped bobbling a ball, I’d hold it away from my body and shout “up,” but regardless of the result, I was always both relieved and frustrated at the end of a play (finding a beep ball feels like finally unsticking a pants zipper).

Having a successful impact on a game you can’t see, meanwhile, an impact which none of the other competitors can see either, leads to storytelling, and blind men congratulated me on great plays that definitely weren’t. Sometimes, because of the speed of the beep or the sound of the scuffling, they did know that one of their teammates had achieved something special. On the flipside, as an inexperienced player, it was hard for me to figure when I’d made a huge blunder. A ball through the legs or agonizingly out of reach isn’t necessarily an error, but high-level players and coaches will tell you that snafus are certainly avoidable. So while some of the pressure’s off, any old unplayable poke down the line can sprout into a myth about so-and-so’s lack of mobility, lack of effort, lack of hearing prowess, lack of human goodness. Blame explodes, and everyone’s potentially right about his interpretation of a play.

“Put twelve blind guys in a room,” Ron told me, “and everyone’s a king. No one can tell them any different.”

One of my few triumphs during the Long Island game was also a humbling failure of agility. In the field, I heard “four,” and the beep came closer. I moved one step to my left and got the ball off my nose. I felt a little moistness like I was about to bleed. This is what I’d been waiting for. Suffering! Authenticity! Beep Ball Passion! (But also Helplessness! And Nostril Pain!). I could take one off the schnozz and live to tell about it, even if I hadn’t made the cleanest play in the world.

Beep ball always includes this mix of impressive athletic straining and comic relief. As exciting as it is to watch three or four guys dive, one after another, the game can also be a blooper video. Missed dives can seem awesome or goofy, but because the fielders don’t know how close they are to collision or to collecting the ball, there’s added urgency. Alfred Hitchcock once said that “surprise” is a sudden explosion and “suspense” is a bomb under a table that the characters don’t know is there. Beep ball’s characters hear the ticking and know the bomb’s close, and every play is a rush to defuse it.

Scratched up, I finished the inning, and the other players said “Where you at?” to the bench as we ran off. The volunteers yelled, “Keep coming, keep coming.” They clapped their teammates in, but April McKaig, the Athens coach, grabbed me.

“C’mon, sweetie,” she said as she took me by the elbow, and I felt, for one split second, the comfort and terror of total reliance. As far as she was concerned, I was blind, and until out number three of inning number six, I was going to stay that way.

• • •

At the World Series, people often treated me as though I couldn’t see. When I bought a Dr. Pepper from a concession girl who guided my hand to the can, it seemed rude to correct her. Others would open doors for me or move into that slightly higher register some people use when talking to those they perceive as weaker. Bruce Stewart, a volunteer for the Indy Thunder, even said, “I can’t help noticing your visual impairment.”

The thing is, I don’t have one, not really. But I do have a pretty severe strabismus—the dreaded wandering eye. When I’m tired, I look like I’m trying to scope out my own left sideburn, and as for actual vision trouble, doctors have told me that my brain fuses images to make up for the fact that I’m not apprehending the thing that’s directly in front of my nose. This leads to some weird moments of near–double vision. While I’m reading, I can see a wall hanging to my left and the right side of the book, but not the left side of the book. On top of that, I’m color blind to a certain degree, and I don’t always see in 3-D (the movies with the protruding fireballs never do much for me). Rembrandt reportedly had this stereoblindness: the eyes don’t work well together and the scene flattens.

I actually don’t know for sure whether my sight is different from the average Joe’s, though. I’m officially 20/20, or thereabouts, and the only troublesome impairment—beyond sensitivity to light—is cosmetic. A doctor warned me once that my adapted brain might not know how to deal with a surgically realigned left eye, so I’ve stuck with the one God gave me, not wanting vanity to rob me of any of my sight. Plus, there’s nothing more unappealing to me than the idea of a scalpel slicing my eye flesh.

Mostly I get along, but I am self-conscious about looking straight at other people. In high school, things were worse, as is the case with most unconventionalities. I got called “Lazy Eye,” and one comedic genius would squint at me for a full minute at baseball practice, chasing me around as he impersonated the way I looked in bright sunlight. My eye, I’ve figured, was probably the way some sophomore girls described me in the concise cruelty of adolescence. I wasn’t the tall guy, or the silly one, or the dude tooling around in the sweet Mercury Topaz.

“Oh, him,” the sophomore hotty might have said to her hotty compatriot, their eyes peering out in perfect, devastating alignment.

As I read—slowly—I’ll always underline descriptions of characters’ eyes, and no line ever got to me as much as this one from Jane Eyre: “His eye wandered, and had no meaning in its wandering: this gave him an odd look, such as I never remembered to have seen. For a handsome and not an unamiable-looking man, he repelled me exceedingly.”

I’ve wondered if my eye has sometimes given people a hard-to-put-a-finger-on-it feeling that I’m unusual to be around. And more importantly, I’ve worried that there’s serious degeneration of my vision on the horizon. Maybe the brain will give up ten years from now, tired of holding together panel one and panel three of the herky-jerky animation in which panel two is missing. Or maybe, in a few months, I’ll see a world of peripheries with no center.

Many people at the tournament asked me what I was really looking for as I reported on beep ball. What was my goal? I’d tell them how fascinating I found the sport and the stories of the people involved, that’s all. I figure they asked me because they wondered if I had a personal connection to blindness. Thankfully I don’t. But I do sometimes catch it glancing at me out of the corner of my eye.

• • •

As I led Athens to a 13–1 loss against Long Island, Ching-kai Chen and Taiwan Homerun battled the formidable Rehab Hospital of Indiana X-Treme, and as we rounded noon on the first day of the series, the sun and the tempers heated up.

Chen lost most of his vision in the instant his motorcycle collided with the car of an elementary school teacher back in 2009. He’d been a star handball player, and in pictures from before the accident he leaps diagonally toward the goal, holding the ball in his left hand high above his head. With his shock of black hair, he cuts a reckless figure as he flies.

In the motorcycle accident, which occurred during his sophomore year in physical education courses at Changhua Normal University, Chen suffered fractures to his right cheekbone and a traumatic brain injury, as well as some temporary damage to his hearing. He was found to have severely deteriorated vision.

Chen had always been athletic growing up—flexible, fast—and because of his handball experience, he has a talent for leaping around converging bodies. But he did this over and over again during the first day of the 2013 tournament, alarmingly. While I saw Chen avoiding collision like a stuntman, his teammate, Rock Kuo, says that’s not always the case: “He has good physical conditions; however, sometimes he bumps into others like a bull in order to catch a ball. This has made other players afraid of being hurt by him.” He wasn’t bumping into anyone in the series, though, and that drew attention his way. Chen routinely treated the beep ball field like his own personal china shop on opening day, romping to the baselines to snag the ball with two hands, and RHI X-Treme pitcher Jared Woodard was the first to question whether Chen was playing fair.

“I saw the guy, first play, up the middle,” Woodard told me later. “He slides over like a normal baseball player would, but as he slides, the ball takes one hop and he catches it at his chest. I’ve seen the best defenders. Heck, my dad’s one of them.” (Jared’s father, Clint, who’s never seen his son’s face, led RHI in putouts in ’13, and no one, Jared thought, could outperform his dad as easily as Chen seemed to.)

“I had the umpire check his blindfold twenty times,” Woodard said. “I could have sworn he was peeking at the plate. And then I could have sworn he was peeking at the base.”

For safety, Chen wore an extra, virtual-reality type facemask over his blindfold that raised questions, too, but the umpires kept ruling that he was legal. I didn’t think much of it. I’d already gotten used to seeing unbelievable stuff on the beep ball field. Woodard wasn’t so trusting.

“They told me he was a pro handball player,” he said. “But that’s eye-hand coordination. Beep ball is ear-hand coordination.”

That night I loitered around a hospitality room in the Columbus Holiday Inn—the host hotel for the tournament—searching for free beers and gossip. Head umpire Kenny Bailey had an open tab. I couldn’t get him to directly address alleged cheating, but later I overheard a meeting he had with the Taiwanese contingent. They were alarmed that their man Chen was under such intense scrutiny, but Bailey told them Chen should take the “looking” accusations as a compliment. He personally promised that their new star wouldn’t be badgered anymore. “Tell him to sleep like a baby,” Bailey said.

Chen wasn’t the first in league history to be suspected of sneaking a peek, and rumors about unfair play are perennial in beep ball, part of the lore of the game. In the eighties, officials stopped a tournament to have an emergency meeting about a particularly successful fielder, but everyone decided to just keep going. A few years later, one star had his head wrapped like a mummy after some highlight-reel plays, but even with the tape and ace bandages he could still pick up the ball quickly. The reason? He practiced year-round in the heat of New Mexico. Third basemen who block line drives with their forearms can become the subjects of florid descriptions and inflated concern, but most of those fables fade with the years.

Taiwan Homerun has heard their fair share of complaints because they’re so good defensively, but also because many in the league don’t know those guys very well. It’s easier to question someone when you can only identify him by his number. Plus, rivalry-thinking can spin out of control. From the ’80s until 2004, I thought every person wearing a Yankees hat was at least a little bit nefarious, and for some of the American players who’ve lost to them repeatedly, Taiwan is the Yankees.

The chatter about peeking seems like one of the stories these guys tell in order to battle. But the hearsay can change the mood of a tournament, with players asking their sighted volunteers to stay vigilant.

The history of suspected “looking” in the sport has had its lighter, outlandish moments, though. In one incident, Bob DeYoung of the Chicago Cobras went to extremes to exonerate himself during a game. When an umpire insisted that he readjust his uneven blindfold, thinking that he might have an advantage, DeYoung removed his prosthetic eyes and handed them over. Dan Greene, league president, was an earwitness.

“We heard Bob’s father say, ‘Robert!,’ and we said, ‘What did he do?’ And his father said, ‘He just gave her his eyes.’”

In a 1521 Domenico Beccafumi painting, St. Lucy, the patron saint of the blind, is depicted holding her eyes out on a platter, and I like to imagine that DeYoung had her satisfied look on his face when he eyed the ump. After all, he’d won that rules dispute more decisively than anyone has ever won any argument in the history of man. Still, “looking” is a heavy topic in this sport. Since playing beep baseball at the very highest level can seem like magic, many think there must be some trick to it, and sometimes the Houdinis of beep are handcuffed by that reputation.

• • •

My Athens team was barely a speed bump for Chen and Taiwan on the first day, but the Timberwolves ultimately snatched two victories in their inaugural tournament, finishing fifteenth out of twenty. After their series ended with a victory over the St. Louis Firing Squad in the losers bracket, they shouted about going to Disney World like they’d started a new dynasty. For my part, I played in two Athens losses against Long Island, but the Wolves still thanked me vigorously for my contributions. It’s possible that “The Author,” as they called me, had made them think of themselves as part of a bigger story, and maybe that motivated Scean and the rest to outlast St. Louis. I allowed the praise, naturally. We shared a few carefully arranged high fives, and an hour after their last game I drove Scean back to the team’s Howard Johnson’s. We talked about a clutch run he’d scored and his chances for a restaurant job back in Athens. We took some wrong turns, but we found the place eventually, the blind ballplayer and the squirrel. He didn’t have his hotel key and wasn’t sure of his room number anyway, so we walked around the pool knocking on doors, searching for our team.

• • •

While the preliminary games took place at a sprawling soccer complex, Austin and Taiwan played the 2013 final in the outfield of Golden Park, a five-thousand-seat baseball stadium that had hosted the 3–1 U.S. victory over China in the gold medal game of the 1996 Olympic softball competition. Taiwan Homerun, undefeated for the week, needed only one win to secure their second consecutive title, while Austin, who’d lost to Taiwan, 7–6, in the previous day’s qualifying round, needed to sweep a doubleheader. Brandon Chesser, Lupe Perez, and Danny Foppiano were rested up, and the game started well for the Blackhawks. Perez, who’d quit high school when he realized during a football tryout for quarterback that he couldn’t see a blitzing linebacker, retired Chen on the second at-bat of the game, chasing one deep in left past the 170-foot home-run line.

“Take it to Taiwan!”

Vincent Chiu, whose engagement to a volunteer had been made final after 2012’s victory, scored on the next play to make it 1–0, though. Then, in the bottom of the first, Austin’s Zach Arambula, a CrossFit fiend who’d scored twenty-four runs in seven games, grounded out to Chen, starting a pattern.

“Ching-kai Chen with the play, again,” said Scott Miller, announcing the game for AM 540 WDAK in Columbus. “This is a guy defensively that Austin has to keep it away from when they put the ball in play,” his color man added.

“Three up, three down. Again, you must keep the ball away from that man up the middle.”

“That is an astounding play. I’ve done baseball for years and years and you won’t see a better play from a sighted player than we just saw right there.”

Taiwan got two runs in the fourth and led 4–0 entering the fifth inning. That’s when things got dire for Austin. Chen raced toward another ball hit by Mike Finn, but instead of colliding with a teammate, he whirlygigged away with a kind of pop-up slide after he grabbed it, and his evasive maneuver was the freeze-frame image of the tournament—an emblem of the athleticism of blind ballplayers, of the near misses that make beep ball thrilling, and of the mystery that surrounds the game’s best plays. The umpires conferred to see if there was anything they should do about the Magician of Changhua. There wasn’t. His blindfold was in place and no one was about to toss a ball at him to see if he reacted.

After another Chen base hit, Austin trailed by five going into the final inning, just as they had in 2012. But in the sixth, Sibson broke through. The ’Hawks were about to make a run. It had been forty-nine years since the advent of the sport, and in this final of the ’13 Series we could finally see it nearly perfected, by a foreign rookie and by a guy who’d been pitching to his blind brother for most of his life. That level of competition had barely been a gleam in the eye of those who first imagined baseball for the blind, but now here it was: international, unnerving, and full of pissed-off players chasing their joy. Baseball by the blind.

Austin was on their way back.

Wayne Sibson’s guide dog, Pacifico, paced the third-base line. Kevin Sibson smacked his glove. Then players and fans stood by for three minutes as Columbus’s emergency alert system performed a beep-nullifying tornado test, the sun shining sharp on all the blackout blindfolds.