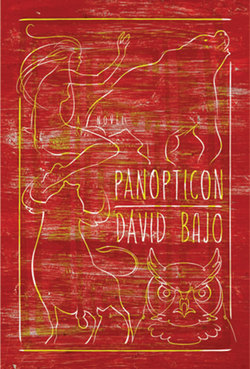

Читать книгу Panopticon - David Bajo - Страница 19

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

14.

ОглавлениеEven after she befriended Aaron in seventh grade, Aracely Montiel never confirmed or denied the bedside visit. When he first reminded her of it, asked her about it in the school lunch yard, she said nothing. The next day she said she didn’t know, maybe she had just dreamed it the night before, a dream induced by Aaron’s question. Subsequent dreams on following nights, of her own snakebite and Aaron’s, only served to bury her true memories. But Aaron knew it.

He lay in his sickbed, unable to sleep, the insomnia that would plague him for the rest of his life already set in at the age of nine. The final late showings of the South Bay and Big Sky drive-ins had flickered off, quiet flames blown out by ocean wind. The flat sweep of borderland lights seemed to shimmer beneath the air, like pebbles on the bottom of a clear stream.

Aracely rose step by step through the floor entrance to the loft. It pained Aaron to crane his neck to see who was coming. He was still hoping to receive a first visit from Az, to hold his hand. Aracely’s skinny little frame lifted quietly into the attic, almost too light to creak the sensitive floorboards. She wore her Mt. Carmel uniform, white blouse, green plaid skirt, and green knee socks. Her black hair was pixie-cut, bangs even as a comb over her brown forehead. Her dark eyes seemed amused. They always seemed amused, he would learn in their later friendship. At nine she had just gotten her real smile, a smart white challenge to everything she said, you said.

Her voice had an intermittent crease in it, an extra curl to the r-sound, sharpening all the words around it. Her English had no accent.

She stood at his bedside, looked him over, lifted her brow at the view he was afforded.

“I know you can’t talk,” she said. “I couldn’t speak for a whole week.”

Aaron moved his eyes, a kind of nod.

“And it hurts for you to move anything.”

He felt tears welling, prayed against them, against the horror of letting a girl—a girl in his class—see him cry.

“Here,” she said, “I’ll show you something.” She pressed her thumb gently into the soft crook of his elbow. Her touch felt cool and deep against his fever.

“It doesn’t hurt here,” she said. “Feels kind of good even. And it doesn’t hurt here.”

She moved her thumb to the hollow of his collarbone. From there the coolness of her touch seeped downward through him, a momentary current against the venom. She raised her foot to the edge of his bed, pushing her knee toward him. She carefully rolled her knee sock down her skinny brown shin and showed him the fang marks. They had become flowerlike scars, tiny rose tattoos.

“They’ll itch for a month,” she told him. “Go ahead and scratch, no matter what they tell you.”

She tilted her head, kept her knee toward him. “Did they tell you?” She challenged her words with a smile, the first time for him. “Did that Mexican guy out there try to tell you? Tell you it won’t kill you? But it will ruin your life?”

Aaron shifted his gaze slightly, a shimmering.

“That’s what they say where I’m from,” she said. “Where the snake’s from. But you have to know Spanish to get it. You speak Spanish?”

Aaron looked down at her scars, then back to her eyes. She recited the saying in Spanish, the quirk in her voice gone without the English r-sound.

“See?” she asked. “They use the word arrasar. Which doesn’t have to mean ruin. Like in English. My nurse told me. After she found me crying through my swollen throat. Arrasara. Almost my name. Arrasara. It will raze your life. You know what that means? You know what raze means?”

She pressed one cool thumb to the crook of his elbow and the other to the hollow of his collarbone. She smiled some more, her new teeth, her woman’s teeth.

The last time Klinsman ran an image search for Aracely Montiel, a year ago, he found only one. It was a photograph of her with two other women at what looked like a fund-raiser. The women were dressed formally, with thin silver necklaces, looking like supportive wives. Ara’s hair was cut short again, the way he had first seen it but with the bangs swept back, matronly. Her smile was the same, too, unmistakable. The caption was brief, locating the event in Jalisco and not naming any of the women.

Except for Connie, Klinsman’s sisters continue to argue that Ara’s bedside visit had to have been a dream. That it occurred so late—after the drive-ins had finished!—served as one obvious clue. How would a nine-year-old girl from a family like that be allowed to do such a thing at such a late hour? And the uniform? This was Liz and Jo’s favorite challenge to the reality of the visit. Even if she had somehow managed to be out after midnight, the idea that Aracely was still wearing her school uniform, the only way Aaron had ever seen her to that point, clearly indicated dream and fantasy. He had probably seen the fang marks on her shin in the schoolyard. Aracely was a fever dream, they told him.

She was your body healing itself.