Читать книгу Empires of the Dead: How One Man’s Vision Led to the Creation of WWI’s War Graves - David Crane - Страница 8

PROLOGUE

ОглавлениеThey throw in Drummer Hodge, to rest

Uncoffined – just as found:

His landmark is a kopje-crest

That breaks the veldt around:

And foreign constellations west

Each night above his mound.

‘Drummer Hodge’, THOMAS HARDY

High on the north wall of Florence’s Duomo can be seen one of the most arresting images of the early Italian Renaissance. Against a deep red background a knight sits on horseback, a spectral figure painted in a cadaverous terra verde that emerges out of the cathedral gloom like some menacing cross between the great equestrian bronze of Marcus Aurelius and Mozart’s avenging Commendatore.

The fresco is the work of Paolo Uccello, and in it Renaissance and Middle Ages meet. The eyes are sightless, the lips drawn back, but astride his ghostly green charger – off-fore raised, neck curved in a gracefully submissive arc – Uccello’s rider still grasps firmly on to his baton of earthly command. Here, simultaneously, is a celebration of life and memento mori, a portrait of power and dissolution, of individual glory and universal mortality, the creation of an age that understood war and death and had seen more than its fair share of both. Pride, fame, blood-guilt, atonement, hope, gratitude – all those complex feelings that lie behind every war memorial – they are all here, and so too is the universal fact of mortality that unites subject and viewer in one common fate. ‘Ioannes Acutus Eques Britannicus’ reads the inscription beneath, ‘Dux Aetatis Suae Cautissimus Et Rei Militaris Pertissimus Habitus Est’ – ‘This is John Hawkwood, British knight, esteemed the most cautious and expert general of his age.’

It seems a perverse irony that the first – and for a very long time only – memorial raised on European soil to an English soldier by a grateful government is Florence’s tribute to the great fourteenth-century mercenary and diavolo incarnato, Sir John Hawkwood. Over the centuries that followed Hawkwood’s death, British armies fought and died across the length and breadth of the continent, and yet anyone walking Europe’s battlefields now in search of some trace of their existence would have about as much chance of finding it as they would the snow off the boots of mythical Russian soldiers marching through the north of England in 1914.

A thin scattering of British graves across Europe does survive – three at Elvas in Portugal, another cluster on the rocky Atlantic-facing slopes above San Sebastián, three from 1813 in the mayoral garden at Biarritz, a few tablets preserved by Napoleon III from the Battle of Toulouse, Bayonne, a tiny clutch on the slopes of the Alma, sixteen in Brussels – but these are almost all the product of family or regimental piety and closer in their air of melancholy to forgotten pet cemeteries than to national monuments.fn1

These are virtually all officers’ graves; the ‘Die-hards’ who fell where they stood at Albuera or the ‘scum of the earth’ who won Waterloo could never expect anything more than a rapidly dug pit and a mass burial. In the immediate aftermath of battle the danger of disease naturally dictated haste, and yet it is hard not to wonder at the failure of imagination or humanity that separated the age which built All Souls, Oxford in memory of the dead of the Hundred Years War, or raised a chantry chapel on the field of Shrewsbury from that which could sanction the post-battle horrors of Waterloo. ‘The countrymen told us, that so great were the number of the slain, that it was impossible entirely to consume them,’ wrote Charlotte Eaton, who had picked her way through the human skulls and fleshless hands jutting out of the earth of Waterloo a month after the battle. ‘Pits had been dug, into which they had been thrown, but they were obliged to be raised far above the surface of the ground. These dreadful heaps were covered with piles of wood, which were set on fire, so that underneath the ashes lay numbers of human bodies unconsumed.’

A complex interplay of social, cultural and religious factors divides the medieval mindset from Waterloo, but a simpler reason is that it took a long time for Britain to overcome a deep-rooted suspicion of its armies. In the course of the nineteenth century something like a rapprochement did occur, but for great tracts of its early modern history, Britain’s European wars were widely seen as ‘ministers’ wars’, or ‘Hanover’s wars’, or ‘Tory wars’, and her armies either instruments of oppression or costly pawns in dynastic coalition struggles that had more to do with an imported monarchy’s German interests than they had with those of a resentful John Bull.

It was not simply a matter of politics, though, because the drunk, the thief, the debtor, the gullible and the unemployed who stocked Britain’s regiments between Cromwell’s God-infused soldiers of Naseby and the citizen armies of the twentieth century, were not easy men to love. Dr Johnson might insist that every man thought the less of himself for not having been a soldier, but one would be hard pressed, as Charles Carrington who served his military apprenticeship in the trenches of the Western Front pointed out, to find much between Shakespeare’s Henry V and Kipling that offered anything like a sympathetic vision of the common soldier.

The sense of alienation was largely mutual and if there were clearly men fired by patriotism – or at least a consistent contempt for foreigners that did just as well – the loyalties that made the British Army so formidable a fighting force were to friends, comrades, regiment and then, just sometimes, their officers. There was a good deal made in recruiting posters of the opportunities for glory in the service of the Queen or King, and yet when all is said, these were men – especially the Irish and Scots – fighting for a society that had found no room for them before they enlisted and from which, when they finished their service, they could expect nothing in return.

From the long perspective of the twenty-first century, when within living memory two world wars have forged a covenant of army and nation, it is hard to grasp how little the armies and great victories of the coalition Wars of Austrian or Spanish Succession, for example, belonged to the nation as a whole. In an age of battlefield tourism, those conflicts are probably now better known and recorded than they have ever been, but generations of British travellers and Grand Tourists, who would happily cross Europe to gaze upon the ‘holy, haunted ground’ of Marathon and Thermopylae, would no more have dreamed of visiting Ramillies or Malplaquet than the young Byron – the first major poet of modern warfare, after all – could bother to make the small detour from his Peninsula travels in 1808 to see where Vimeiro had just been fought and won by Wellington’s men.

This lack of connection did not stop the Votes of Thanks in Parliament, the busts and statues in Westminster Abbey and St Paul’s, the building of Blenheim Palace, the patriotic odes or the sporadic outbursts of national triumphalism, but there was no genuine sense of national identification. In the early phases of the struggle against Napoleon, the fear of invasion created something like a national consensus, and yet even Waterloo – the first British battlefield to become a shrine for tourists – was fought against a rainbow opposition of Whig, mercantile and radical opinion that left a great swathe of the country deeply resentful of the ‘abuse’ of British power in the service of a bloated Catholic despot like Louis XVIII.

In the age of the Peterloo Massacre and the ‘Piccadilly Butchers’ – that mini-ice age when the military were used as an instrument of civil power – it is not surprising that the old historic dislike of a standing army persisted, but Waterloo still represents a watershed. It is impossible to put a date to anything so gradual as a shift of public consciousness, and yet in the diaries and travel journals of English men and women in the years after 1815 it is possible to trace a change in that triangular relationship of government, army and people that begins with Waterloo and victory over Napoleon, and is still played out in the press over every defence cut or equipment deficiency that might threaten soldiers’ lives overseas.

This healing process that began with Waterloo – and was finally, and permanently, sealed by the fighting courage and stoic heroism of the common soldier in the Crimea – was in its turn part of a wider social change that affected the Army as much as it did every other aspect of British life. The list of the dead and wounded in Wellington’s Waterloo despatch might just as well have been torn out of Debrett’s, but the heroes of the Crimea and Indian Mutiny were made of different stuff, men such as William Peel and Henry Havelock or Captain Hedley Vicars, who were closer in their high-minded earnestness and Bible-carrying piety to the new middle classes of England from which they sprang than to their Godless predecessors of Badajoz and San Sebastián.

This convergence of identities was important for changing attitudes to the Army, because it coincided with that growing sense of national prestige and providential ‘destiny’ that was to become such a feature of British attitudes during its imperial heyday. Since the time of the Reformation, a profoundly Protestant belief in a divinely appointed national ‘election’ had entered into the English psyche, and as the country emerged from the Napoleonic Wars as the world’s pre-eminent power, this growing sense of predestined mission helped turn her armies from the tools of arbitrary government to place them and the Empire they were creating squarely in the vanguard of Christ’s Second Coming.

Gone were the days when Byron could sneer that ‘after Troy and Marathon’ the field of Waterloo was ‘not much’; gone the Lilliputian embarrassment of Hazlitt when he compared moderns and ancients; gone the sense that Benjamin West’s painting of the death of General Wolfe was an act of blatant lèse majesté. For the eighteenth-century artist, the proper business of history painting might have been the classical past, but to West’s successors of the nineteenth century the natural subject matter of art was not so much the doings of Regulus or Agrippina as the defence of the Coldstream colours at Sandbank Battery, or the Thin Red Line, or the bald-headed heroics of the Marquis of Granby.

Along with this burgeoning sense of pride went a deepening sense of responsibility to the country’s army and the country’s dead. ‘Would it have been possible, think you, to have concealed and slurred over our failures?’ demanded W. H. Russell, the great Times war correspondent who brought home the incompetence of the High Command in the Crimea to a British public demanding aristocratic heads; ‘No: the very dead on Cathcart’s Hill would be wronged as they lay mute in their bloody shrouds, and calumny and falsehood would insult that warrior race, which is not less than Roman, because it too has known a Trebisand and a Thrasymene.’

With the desolating Retreat from Kabul behind them, and the horrors of the Indian Mutiny only months ahead of them, Victorian England was getting used to extracting what comfort it could out of defeat. Here, however, is a note that would not have been heard even forty years earlier. Through the summer of 1815 there had certainly been collections and subscriptions the length of Britain for the widows and orphans of Waterloo, but the sense of responsibility and debt that Russell articulates, the recognition that the dead of the Crimea had their claim on the life of the nation was something very different in the relationship of Britain and her army.

It was one thing to talk like this, one thing for the Americans to hallow the soil of Gettysburg – it was American soil and American dead on both sides – but it was another to turn a distant piece of Russia or Turkey or any other bit of Europe into a little piece of England. At the end of the Crimean War in 1856 there had been 139 cemeteries of varying sizes scattered on the heights around Sevastopol and the Alma, but within twenty years this number had shrunk to eleven and then to one, as a hostile world of nomadic grave-robbers, winter frosts, earthquakes, vandals and grazing cattle took its random revenge on the men who had humiliated Mother Russia and reduced Sevastopol to ruins.

Perhaps the only surprise is not that there are so few surviving graves from Britain’s eighteenth- and nineteenth-century European wars, but that there are any at all. For those who cheerfully suffered the miseries of a Crimean winter, the work of the British Army in the Crimea was manifestly Christ’s work, but for all those countries that Britain fought against or even with, for Islamic Turkey or Orthodox Russia, for its Soviet successors who found themselves the custodians of Lord Raglan’s viscera, or Spanish nationalists recalling the sack of San Sebastián, the graves of Britain’s soldiers were not the sacred places of a burgeoning British mythology, but symbols of national humiliation, exploitation and desecration.

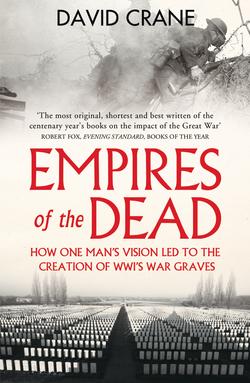

And then, out of nowhere, all that changed. In 1914 the number of surviving British war graves from Portugal to the Ionian Isles could be counted in their handfuls. Four years later they numbered in their hundreds of thousands. A war that had been fought on a hitherto unimaginable, industrial scale had been commemorated in kind. Something like a million British and Empire soldiers, sailors and airmen had been killed and on gravestones, memorials and monuments across the battlefields of the Western Front, Palestine, Mesopotamia, East Africa, Greece and Italy the task had begun of ensuring that their names would not be forgotten. ‘Imagine them moving in one long continuous column, four abreast,’ an early commentator at the Cenotaph Armistice Day service once said, giving graphic visual meaning to the sheer scale of the task that Britain had taken on,

as the head of that column reaches the Cenotaph the last four men would be at Durham. In Canada that column would stretch across the land from Quebec to Ottawa; in Australia from Melbourne to Canberra; in South Africa from Bloemfontein to Pretoria; in New Zealand from Christchurch to Wellington; in Newfoundland from coast to coast of the Island, and in India from Lahore to Delhi. It would take these million men eighty-four hours, or three and a half days, to march past the Cenotaph in London.

It is hard to know what is more extraordinary, the success of the attempt or the seismic shift of sensibility that brought it about in the first place. A ‘corner of a foreign field’ that for centuries had been no more than a scattered collection of neglected graves could now only be bound by walls fifty miles in length. How was it that nations and governments that had squandered lives in such obscene profusion could suddenly become so protective of their memory? How was it that a post-war Britain marked by class division and mutual suspicion could achieve its most democratic expression in the celebration of its dead? How did a country and empire that was historically so inimical to militarism and regulation, find its most potent expression of ‘Britishness’ in the straight lines, regularity, and enforced conformity of its war cemeteries? What, ultimately, lies behind these cemeteries and memorials? Grief? Pride? Gratitude? Guilt? Atonement? Reparation? Political acumen? Which was it? Catharsis, or ‘the old lie’ – ‘Dulce et Decorum est’ – that the poet Wilfred Owen, killed in the last week of the war, wrote of?

The fact that these questions are not more often asked is a tribute to the remarkable success with which the process of commemoration was carried out. Success carries with it a sense of its own inevitability and the images of Britain’s war cemeteries – the immaculate rows of graves, the memorials, the flowers and Crosses of Sacrifice, the biblical inscriptions – are so visually and imaginatively compelling that it is hard to realise that there was nothing preordained or self-evident about them. Nor, either, were they once the sacred cows that they now are. They did not appear without a struggle. They were as much the product of debate and argument as they were an expression of national unity, and they brought about divisions that were bitter and lasting. This is now largely, and perhaps properly, forgotten but it would have been surprising if it had been any other way. A traumatised society was dealing with death, grief, pride and anger on an unprecedented scale and it had little to guide it. A nation characterised by a deep and self-conscious class awareness was forced to cope with a war that was as indiscriminate in its killing as the plague. Where, in the twentieth century, was it to find the equivalent of that universality of understanding that raised Battle Abbey, or lies behind the Uccello memorial? How was it to balance the claims of the individual and of the nation? How does a Christian society remember its Muslim, Hindu or Jewish dead? How does it juggle the just claims of victory and the dictates of a wider, healing vision? How, even before you have begun to address these cultural questions, do you begin the vast task of commemorating the million casualties of a war that obliterated every vestige of human identity in the way that the great battles of the Western Front had done?

That answers were found and took the form they did is largely the work of one man. They came at the end of a century that had seen a gradual but profound change of attitude to its armies. They came too just a year after the centenary of the Battle of Leipzig and the fiftieth anniversary of Gettysburg had raised the Western world’s consciousness of its historical debts. And they emerged, of course, from long cultural traditions, from the country’s Christian roots, and from a human piety that is older even than those. If history can ever be said to belong to the individual, then it is the history of Britain’s war cemeteries and the process by which they came into being. Along with the trenches – their mirror image and polar antithesis – they are how most of us now see the First World War. And yet the identity of the man responsible for them is largely forgotten. Almost everyone, asked for the name of the commander responsible for the slaughter of the Western Front, would, fairly or not, come up with Haig. Most, asked for the architect of the Cenotaph, could make a stab at Lutyens. But the man who mediated between them, who made it possible for a country to come to terms with the slaughter and unbearable debt it owed its dead, is scarcely better known now than the unidentified thousands whose graves only bear the inscription ‘Known unto God’. His name was Fabian Ware.