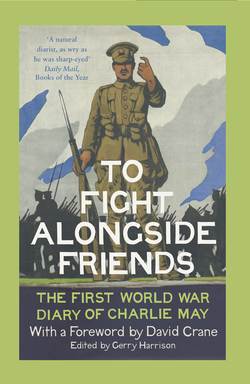

Читать книгу To Fight Alongside Friends: The First World War Diaries of Charlie May - David Crane - Страница 10

Foreword

ОглавлениеWhat is it that makes one diary live and another simply die on the page? Nine times out of ten it is down to the intrinsic interest of the material or the quality of the writing; but every so often one comes across a diary where it is the sense of personality behind it that lifts it out of the ordinary: such a diary is that of Captain Charlie May, killed in the early morning of 1 July 1916, leading his men of B Company of the 22nd Manchester Service Battalion into action on the first day of the Battle of the Somme.

There is nothing very remarkable about Charles May, and that is the point about him: from the first page of his diary to the last haunting entries he feels so utterly familiar and recognisable. That is partly because his war was the war that a million men like him knew and endured and has become part of our historic consciousness; but more than that it is because Charlie May is ‘England’ as England has always liked to imagine itself, the England that stood in square at Waterloo and would stand waist-deep in water at Dunkirk, the England of a hundred 1940s and ’50s films, down to his English wife and his English baby daughter and the English batman and the Alexandra rose that he sports into battle – the unassuming, modest, enduring, reliable, immensely likeable kind of Englishman, with his kindness, his tolerance, his loyalty, his certainties, his prejudices, his pipe, his fishing rod, his horse, his good jokes and his bad jokes and his un-showy patriotism, that if you had to spend your war up to your knees in clinging mud you would be very grateful to find next to you: and he is absolutely genuine.

I do not know if it is odd that someone so quintessentially English should come from New Zealand, or if that is part of the explanation, but Charlie May was born in that most stonily un-English of towns, Dunedin, on 27 July 1888, the son of an electrical engineer who had emigrated five years earlier. His father made his name and the foundation of a successful business with a patent for a new kind of fire alarm device, and on their return to England, Charlie had entered the family firm of May-Oatway, acting as company secretary before moving with his new wife, Maude, from the Mays’ family home overlooking Epping Forest to Manchester where, just two weeks before the outbreak of war in 1914, a daughter, Pauline, was born. It is clear that the Mays did not lose sight of their New Zealand lives – their Essex home was named ‘Kia Ora’ (‘be well’ in Maori) and Charlie would call his new home ‘Purakaunui’, after a pretty coastal settlement, near Dunedin – but in 1914 there would have felt nothing odd about such a double identity. It was famously said that sometime between the landing at Anzac Cove and the end of the Battle of the Somme the New Zealand nation was born, but in the late summer of 1914, before Gallipoli was ever dreamed of, many of the thousands of New Zealanders who volunteered to fight in a war half a world away would have seen themselves as part of a single imperial family, one corner of the great Dominion ‘quadrilateral’ of Canada, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand, on which the British Empire rested.

While still in the south May had been a member of King Edward’s Horse, a Territorial unit of the London Mounted Brigade with strong Dominion links, and, daughter or not, it was only a matter of time before war put an end to his short married idyll. On the outbreak of hostilities five divisions of a small but highly trained British Expeditionary Force had immediately been embarked for France to stem the German advance, but Kitchener for one never had any illusions that this was going to be a short war over by Christmas and within the month the first 300,000 of a New Army had responded to his call for volunteers.

By the end of September another 450,000 had volunteered, in October a further 137,000, and in the following month Charlie May enlisted into the 22nd Manchester Pals battalion – the ‘7th City Pals’ – and added his name to the five million men who would wear uniform of one sort or another before the war was over. The idea of the ‘Pals battalions’ had first been put to the test in Liverpool by Lord Derby and the city of Manchester enthusiastically followed suit, embracing the patriotic and civic ideal of a battalion made up of friends from the same street, pub, factory, profession, warehouse or football club, joining up and fighting together – ‘clerks and others engaged in commercial business,’ as Derby put it, ‘who wish to serve their country and would be willing to enlist in a Battalion of Lord Kitchener’s new army if they felt assured that they would be able to serve with their friends and not to be put in a Battalion with unknown men as their companions’.

It was a sympathetic initiative, if a double-edged one as time would bitterly show, but in the late summer of 1914, as towns across Britain competed with each other in displays of civic pride, the slaughter that would engulf whole tightly knit communities in grief still belonged to an unimaginable future. Within hours of the Lord Mayor of Manchester launching his appeal in the Manchester Guardian on 31 August, volunteers were besieging the artillery barracks on Hyde Road and by the end of the next day 800 men had been sworn in and the establishment of the first of the Manchester Pals battalions, the 1st ‘City’, or 16th Service, was complete. Over the next four days another two battalions were added, and after a late summer lull in recruiting caused by the frustrating long queues, a further three battalions in November, the 20th, 21st and Charlie May’s 22nd under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Cecil de C. Etheridge.

It would be exactly a year before Charlie May and his battalion embarked for France, and in that time an enthusiastic but improbable bunch of men drawn largely from the cotton industry and City Corporation – ‘mostly town bred’, wrote May, with a rare whiff of the King Edward’s Horse and the Empire – had to be turned into soldiers. In these early stages before their khaki uniforms arrived, they wore the ‘doleful convict-style’ ‘Kitchener Blue’ and ‘ridiculous little forage cap’ so deeply resented among the New Army, but over the next twelve months, and in the face of the universal shortages of uniforms, weapons and ammunition and every provocation and indignity an army could dream up to frustrate, bore or disillusion a civilian volunteer, the job was at least begun.

It would be as late as October 1915, by which time the 22nd were at their final camp on Salisbury Plain as part of Major General Sir William Fry’s 30th Division, before the artillery could even start firing practice or their Lee Enfield rifles and machine guns arrive. If May’s diaries from France are anything to go by, he would have taken the frustrations in his stride. With six years’ experience in the King Edward’s Horse behind him he had received his commission back in January, and he was a company commander when, in the middle of November 1915, after a last few days’ leave to see his wife and sixteen-month-old daughter, Captain Charlie May and the 22nd Battalion finally embarked from Folkestone for Boulogne.

The war that Charlie May had been trained for was not the fluid conflict of retreat and advance that the BEF had known in 1914 but the war of trenches that is how most of us now think of the First World War. In the popular memory the year 1915 seems almost like a pause between the heady optimism of the opening weeks of war and the slaughter of the Somme, but while May and the 22nd were shuffling from camp to camp – Heaton Park, Morecambe Bay, Grantham, Lark Hill – and progressing from longish ‘walks’ to bayonet and bomb practice, the bloody failures of Aubers Ridge, Festubert and Loos were teaching a bereaved nation the appalling reality of warfare along the 475 miles of earthworks and trenches, stretching in an unbroken line from the Channel to the Swiss border, that we know as the Western Front.

It was to this static, troglodytic war of attrition, mud, rats, sleeplessness and endurance that May was bound and it is as they finally set off for France that his diary begins. In the last two or three years of peace Charlie May had begun to establish himself as a journalist and writer, and the diary is unmistakably the work of a born story-teller, a man with a lyrical sense of place, an ear for dialogue, a gift for rapid and vivid characterisation, a taste for the incongruous and a need to record what he saw and experienced. ‘One gets into a habit, quite unconsciously at first, of any hold it may subsequently get on one,’ he was confessing less than a month after landing in France. ‘For instance, here did I set out, gaily and with no foreboding, upon this diary, never thinking it could become a tyrant that would ’ere long rule me, and here I am reduced to impotence when evening comes round, unable to refuse the call of these pages to be scribbled in … But fill it I must, this habit has me so in its grip.’

Charlie May’s war diaries survive in seven small, wallet-sized pocket books, written in faint pencil in his neat but tiny, italic hand, as a rich and vivid testament to this compulsion. At one level it seems rather curious that an officer of his dedication should indulge in something so defiantly in breach of King’s Regulations, but we can be grateful that he did because the result is an account that had never seen the censor’s eye, a vivid picture of battalion life in and behind the trenches during the build-up to the greatest battle fought by a British Army.

The friendships and tensions, the homesickness, frustrations, delays and endless postponements, the fog of ignorance, the combination of boredom and terror that every man who has ever fought could testify to, the relationship of officer and batman, the almost incomprehensible contrast of the pastoral world only miles behind the fighting and the scarred and pocked ugliness of the front line – all familiar enough, perhaps, but seen and recorded here with a freshness that brings them home as if for the first time. ‘This war, I am sure, is one of the most peculiar the world has ever known if, indeed, it is not the most peculiar,’ he writes of the surreal experience of facing an enemy you might never see,

In no other can it have been possible to soldier so long, to witness such evidence of the presence of an enemy and of his ability to injure without ever catching sight of beast, bird or man belonging to him … Except through my glasses, I have never yet seen a Fritz – an experience in no way peculiar, since it has been experienced by many a thousand others of double my active service.

There is a visceral immediacy about a war diary – a question mark hanging over each entry, the unspoken possibility that it might be the last – that no retrospective account can quite match. But the main fascination of these pages remains Charlie May himself. There is material here – details of units, movements, coded map references (which have been omitted from the text) – that would plainly never have got past an Army censor, but it is the absence of self-censorship that makes these diaries so compelling and disarming a portrait of the archetypal English ‘Everyman officer’ – ‘a truly ordinary sort of clout-head’ as he describes himself – shorn of all the reticences and defences behind which he traditionally hides.

There is no cynicism or pretence in these pages, no attempt to make things sound better or worse than they are, or to dissemble the depth of his feelings for the men under his command or the wife and daughter to whom his diary is addressed. In Robert Graves’s Goodbye to All That, any talk of ‘patriotism’ was fit ‘only … for civilians, or prisoners’ and any new arrival would soon have it knocked out of him. Underscoring every page of May’s diaries, however, is an unembarrassed pride in his country and an almost maternal affection for the Englishmen with whom he is privileged to fight.

It has its ‘little Englander’ side – ‘I can’t imagine why the Germans want this country,’ he quotes one of his messmates on the irredeemable squalor of the ‘hairy, dirty, baggy-breeched’, sabot-wearing French peasant; ‘If it was mine, I’d give it to them and save all the fuss’ – but in nothing is he more an Englishman of his time than in his less attractive prejudices. He can write very movingly of the shattered lives and homes that they come across in the villages behind the front lines, but he only has to see or smell another French midden to feel a sudden, nostalgic, humorous tug of affection for ‘Dear, old, tax-ridden, law-abiding England!

How I would delight to see one of your wolf-nosed sanitary inspectors turned loose in this, our Brucamps. How you would sniff, how snort, how elevate your highly educated proboscis! … And how masterly indifferent would our grubby people be of you, how little would they be impressed, how hopelessly insane they would think you, and what grave danger there would be of a second Revolution if you or any untold number of you essayed to remove from them their beloved dung-heaps.

It is the same with the ‘British Tommy’. He might lose his kit as soon as look at it, he might need ‘booting along’ or a good ‘strafing’ – May’s favourite word – he might get drunk, he might be ‘something of a gross animal’, but ‘God knows he has enough to put up with. And I cannot help but love him.’

‘Men dropped by the road side exhausted,’ he writes in one wonderfully evocative passage,

Others staggered pitifully along in bare feet, the mud having snatched both boots and socks from them. Others again went strong, chattering and laughing whilst among the lot the officers, those of us whose strength was equal to it, went in and out carrying a rifle for this man, giving a cigarette to another, helping a lame duck up on to his poor, swollen feet again and chaffing or cracking feeble jokes with them all … It was a dark night. Men were but shuffling shadows against the chalk mud of the roadway except when the lights went up from the lines all about us. Then you could see the huddled forms of tired, mud-caked Englishmen shuffling home from their labours. The war is a war of endurance. Of human bodies against machines and against the elements. It is an unlovely war in detail yet there is something grand and inspiring about it. I think it is the stolid, uncomplaining endurance of the men under the utter discomforts they are called upon to put up with, their sober pluck and quiet good-heartedness which contributes very largely to this. All the days of my life I shall thank God I am an Englishman.

It does not stop him grumbling at all the usual targets of the infantry officer – the staff officer with nothing but a public school to recommend him, the deliberate idiocy of the censors, the base camp shirkers who would be all the better for a week in the trenches, the public at home querulously wondering why the Army isn’t ‘moving’ – but nothing in the end can dent his faith. It is possible that had he lived to see where his blind confidence in the build-up to the Somme led he would have shared in the general disillusion, but any man who can extract comfort out of Loos or the disastrous fall of Kut or ‘Thank God for the Navy’ a week after Jutland is probably proof against anything that even the Great War can throw at him.

There was nothing abstract about May’s patriotism; that was the strength of it. It was embodied in the men he was fighting with – in Bunting, his loyal batman, who had pulled him out of the canal when drunk one night in Manchester; in the puzzling Richard Tawney who, for whatever reasons of his own, went on refusing a commission; in the ‘pitiful sight’ of ‘Poor English soldiers battered to pieces’; in ‘Gresty … a good man and one whom we liked well … his poor body full of gaping holes’ – and it made May want to fight. ‘Do those at home yet realise how their boys go out for them?’ he asked,

Never can they do enough for their soldiers, never can they repay the debt they owe. Not that the men ask any reward – an inviolate England is enough for them, so be it we can get our price from the Hun. Confound the man … But one day we’ll get at him with the bayonet. The issue must come at last to man to man. And when it does I have no doubt as to the issue. We’ll take our price then for Gresty and all the other hundred thousand Grestys slain as he was standing still at his post.

It needs to be remembered that the 22nd was also the ‘7th City Pals’, and the strong friendships and loyalties around which the whole concept of the Pals battalions had been initiated made such losses seem more painful still. By the time that the Battle of the Somme began, the battalion formed in November 1914 had of course changed with time, deaths, promotions and new arrivals out of all recognition, but one only has to look at the parallel accounts of May’s old comrades from the Morecambe, Grantham and Lark Hill days – fascinatingly incorporated here as footnotes to his own diary entries to add fresh perspectives – to feel how strong were the bonds formed in England in a battalion like the 22nd and how bitterly the losses were mourned. ‘Tonight we had a little reunion of all the old boys,’ May himself wrote just a week before the Somme began,

There was the doctor, Murray, Worth, Bill Bland, ‘Gommy’, Meller and myself and we sat round a table and sang the old mess-songs … It was tip-top and we all loved each other. There are so many new faces with us now and so many missing that the battalion hardly felt the same – and one cannot let oneself go with the new like one loves the old boys. I would that the battalion was going over with all its old contingent. How certain we should all feel then. Not that the new stuff is not good. But we knew all the others so well.

Above all though, for Charlie May, England was his wife Maude and their baby daughter Pauline; his diary is an extended and deeply moving love-letter to them. He had married Bessie Maude Holl in February 1912 when they were both twenty-three, but it was really only when he had to leave her and their new daughter, that they both seem to have realised – not how much they had loved each other, that never seems to have been in any doubt – but how astonishingly fortunate they had been in their brief, shared lives. ‘I thought of you as we strolled there, Lizzie with her reins slack wandering where she would and at her own pace,’ he wrote after one afternoon spent riding through a world of larch and birch clumps and wood pigeons still untouched by war – a passage in which images of Maude, England and a deeply felt sense of natural beauty fuse into one to take us as close as we can probably get to what it was that Charlie May was ready to fight and, if necessary – un-heroically, reluctantly but matter-of-factly – die for.

And I longed that you could have been with me, for I know how you would have loved it and how happy we two would have been. The green rides of Epping came back to me in a flash. You in that black spotted muslin dress you used to wear looking cool and lovely so that I just asked nothing more than to walk along and gaze at you dumbly, like any simple country lout gazes at his maid.

‘I do not want to die,’ he wrote; the thought of never seeing Maude again, of his daughter growing up and never knowing him, turned ‘his bowels to water’. But as the sporadic tours in the front-line trenches and the training behind the lines intensified in the build-up to the expected great summer offensive of 1916, there became less and less room for the ‘personal’. It is impossible to read these diaries and the first casual mention of the Somme without a sense of grim foreboding, and yet at the same time there is no missing the growing excitement at the approach of battle, at the movement of troops, the massing of guns in preparation for the preliminary bombardment and the submersion of the individual in a mighty collective whole. ‘It is marvellous,’ he wrote, ‘this marshalling of power. This concentrated effort of our great nation put forward to the end of destroying our foe. The greatest battle in the world is on the eve of breaking. Please God it may terminate successfully for us.’

There had been ominous warnings for the 22nd in the weeks leading up to the Battle of the Somme – a night raid with heavy casualties that showed the German wire uncut by the artillery, dud shells and ‘whispers’ that ‘our ammunition … is not all that it should be’ – but the grief that the word ‘Somme’ would conjure up for thousands of families whose sons had flocked to enlist in the autumn of 1914 belongs to retrospect. To Charlie May the word meant only a glimmering river – ‘full of sport’, he thought it should be, as he set off to buy his fishing tackle in Corbie – idling quietly through a landscape of ‘tiny panoramas’ of bullrushes and pampas grass, of ‘brown trees, blue, sparkling waters, white, brown, red, blue and purple houses clustering around their grey churches’. The larger picture, the overall strategic concerns and aims that lay behind the Somme offensive of July 1916 – Verdun, the Eastern Front, the eternal illusion of a ‘break-through’ – were of no concern. His Great Battle – the battle that would mark ‘the beginning of the end’, he told Maude on 15 June – would be what he called the ‘Battle of Mametz’, and his responsibilities were to the men around him and the wife and daughter who were never out of his thoughts.

On the morning of the first of July, after a week of preliminary bombardment, the 22nd were part of the 7th Division, and their sector lay opposite the heavily fortified village of Mametz, on the southern edge of the Germans’ Fricourt Salient, east of Albert. On their left the British line stretched up northwards through names that would soon be seared into the national consciousness – Fricourt, La Boisselle, Thiepval, Beaumont-Hamel – and on their right, eastwards and south to Maricourt, the junction with the French army and the River Somme itself. But for the company commander of B Company, the war had shrunk to the ‘900 yards of rough ground’ in front of him and the inner battle to live up to the standards he had set himself. ‘My one consolation,’ he wrote to his wife, in one final, simple and binding credo,

is the happiness that has been ours … My darling, au revoir. It may well be that you will only have to read these lines as ones of passing interest. On the other hand, they may well be my last message to you. If they are, know through all your life that I loved you and Baby with all my heart and soul, that you two sweet things were just all the world to me. Pray God I may do my duty, for I know, whatever that may entail, you would not have it otherwise.

The diary would be the last word she had from him. He did his duty, and so, too, did the battalion of whom he was so proud. ‘They are all so clean-cut and English as you know so well, my own,’ he had written to his wife on the eve of their departure for France; ‘I feel confident they’ll go when the chance comes. Please God the 22nd may carry the old Regiment’s name another rung up the ladder of fame.’ His soldier’s prayer was answered. If his optimism in the prosecution of the war was unfounded, his confidence in the courage of his men was not. He would not live to know it – his last moments are preserved here in his wife’s desperate, unbearable need to know every detail of his end – but Mametz was taken and, almost uniquely, the battalion’s targets all met. It had been, though, at a shocking price. Of the 796 officers and men of the ‘7th City Pals’, 472 were either killed or wounded on that terrible 1 July, a day that would cost the British Army 19,240 dead and 57,470 casualties in all. May’s Battle for Mametz was over but the Battle of the Somme had only begun.

David Crane

February 2014