Читать книгу The Kindness of Sisters: Annabella Milbanke and the Destruction of the Byrons - David Crane - Страница 5

I A MEETING OF OPPOSITES

ОглавлениеOn a chill and blustery Tuesday in April 1851, an elderly woman, accompanied by a man in his early thirties, emerged from the entrance at the top of Trafalgar Street in Brighton to take the north-bound railway for Reigate. If anyone in the crowded terminus had noticed either of them it would almost certainly have been the man, a tall and striking figure, whose charismatic preaching at the Holy Trinity had made the names of ‘Brighton’ and ‘Robertson’ synonymous across the English-speaking protestant world.

With her air of genteel invalidism, and discreet, unassuming appearance, it is unlikely that the woman beside him would have attracted a second glance. She had never been more than five foot three in height and in her late fifties seemed scarcely that, a fragile, neat creature with a slight, ‘almost infantine’20 figure, fine delicate hands, deep and striking blue eyes, silver hair, high forehead, and the preternatural pallor of the permanent invalid.

To the circle of her friends, in fact, who watched over her prolonged decline with a complete and willing devotion, it seemed that Annabella Byron hardly belonged to this world at all. There was a calm certainty about her that struck a note of unearthly detachment, an ethereal refinement that seemed to the chosen ‘soulmates’ of these last years to be that of ‘one of the spirits of the just made perfect … hovering on the brink of the eternal world’21.

If anyone had taken a closer look at this pair, however, as they made their way under the soaring gothic of Brighton’s new terminus to the first-class carriages of the London train, there would have been little doubt where the balance of power lay. Thirty five years earlier the young Annabella Byron had appeared to her sister-in-law less as a visiting angel than an avenging spectre, and in the remote and concentrated self-possession of her bearing, it was as if all the frailties or pleasures of life had been purged away to leave behind only a pure, indomitable will.

And yet behind this ‘miracle of mingled weakness and strength’22, as Harriet Beecher Stowe called her, there was a nervousness, an emotional and physical excitability, that raged all the fiercer for its ruthless suppression. In a self-portrait she wrote in the last year of her life she spoke of the ‘burning world within’23 that so few ever saw, and as she took her place beside Robertson, and sat compulsively folding and refolding her scrap of paper with its illegible instructions to herself on it, she knew only too bitterly the cost at which any outward calm had been won.

If she had caught her reflection in the glass before it was swallowed up in the blackness of the Clayton tunnel, she would have been forced to recognise there the evidence of the same grim truth. Forty years earlier, in her second London season, Hayter had painted her with the louche abandon of some Regency Magdalene, but if she had looked now for the face of the young Annabella Milbanke in the reflection that stared back, searching for some trace of all those potentialities and hopes that were frozen when pain and humiliation petrified her strength into the obduracy of a long widowhood, she would have looked in vain.

There would have been something in its unyielding expression, however, in the set of the mouth, in the air of conviction, the concentration, that anyone who had seen her as a child would have had no difficulty recognising. Some years after her death Robertson’s biographer, Frederick Arnold, remarked on the doctrine of ‘personal infallibility’ to which Annabella Byron subscribed in these late years, and if a lifetime of alternating sycophancy and hostility had done their worst to make her what she was, the foundations at least of her old age were laid in the cosseted, self-absorbed childhood of Annabella Milbanke.

To have any real sense of the woman in the train bound for Reigate, or the forces that had shaped her life, it is necessary to go back even further than that, to another generation and world that is best glimpsed in a family portrait by Stubbs that now hangs in the National Gallery in London. On the left of Stubbs’s grouping a young woman of seventeen sits high in the seat of a light carriage, reins and whip competently and prophetically in hand, her face, simultaneously ‘unfinished’ and determined, framed by a white bonnet, her eyes boldly, almost immodestly, engaging with a future that seems in her control.

The girl, Elizabeth Lamb, is pregnant, although it is impossible to tell from the painting. At her side, her father, Sir Ralph Milbanke, his expression serious, leans against the carriage; in the centre, holding the reins of a dappled grey that matches her carriage pony, stands her brother, John; on the right, slightly apart, elegant in profile on a superb bay, is her husband of a year, Peniston Lamb, the future first Lord Melbourne.

There is a sense of calm to the piece, a reserve and unforced serenity that can only come of an unconscious collaboration of artist and sitters. In the distance a rocky outcrop looms over a stretch of water with some vague suggestion of domesticated wildness, but Stubbs’s figures need no background, confidently filling their social and pictorial space, sufficient to themselves under the enveloping protection of a darkly spreading oak.

The oak and the girl, the past and the future, both linked in an unbroken chain to which the figures bear silent, unruffled witness. There is no conversation in this ‘conversation piece’, no interaction almost, just a shared strength that needs no articulating. From the side Peniston Lamb looks across – as well he might – to his formidable young wife, but the gaze is unreturned. Even the horses seem entirely self-contained, blinkered or cropping the grass, indifferent to each other, their owners, or the two dogs that, like a pair of attendant saints, stare up, in that eternal gesture of English portraiture, with unnoticed devotion at their masters.

There is none of the golden glow of other Stubbs paintings here, none of the bucolic ease of his Haymakers, but a cool silvery light warmed only by the pink of Elizabeth’s dress and the answering tinge of the clouds. On a nearby wall an elderly couple also painted by Stubbs aboard their phaeton might be Jane Austen’s Admiral and Mrs Croft, but this group is not about affection or fulfilment but hierarchy and power, about dynastic and cultural certainties, and about what David Piper memorably called that ‘obscure but potent directive of fate’ that gives Stubbs sitters their air of unchallenged and unchallengeable authority.

According to tradition, the Milbanke family traces itself back to a cup-bearer at the court of Mary Queen of Scots, who fled the country after a duel, settling in the north of England. Whatever the maverick promise of these origins, however, the next two hundred years saw a blameless decline into respectability, all taint of romance erased, in a family progress that took the Milbankes from Scottish exile by way of aldermanic and mayoral office in Newcastle to a baronetcy and a safe seat in Parliament.

It was Charles II who granted the title to the first Sir Mark Milbanke in 1661, and over the next century the Milbankes’ influence was consolidated in the network of alliances and marriages that inevitably underpinned eighteenth-century political life. In generation after generation of Sir Marks or Sir Ralphs the same pattern emerged, as the Milbankes of Halnaby Hall married into other northern families, extending their land and connections across the north-east of England, augmenting agricultural interests in one marriage or mineral interests in another before, in the middle of the eighteenth century, forging the key alliance with the powerful Holderness family that gave Stubbs’s 5th Baronet a place in the Commons.

There is something so reassuringly dull about the Milbankes’ political careers, so entirely lacking in individuality, that one feels instinctively with them that one is in touch with the solid bedrock of Sir Lewis Namier’s England. Sir Ralph had first entered parliament as one of two unopposed members for Scarborough in 1754, and at the first election of the new reign stood in the Holderness interest for Richmond, loyally and uncritically supporting successive administrations, before retiring in 1768 without having spoken a single word in fourteen years an MP.

Over twenty years were to pass before another Milbanke sat in Parliament, but through the 1770s and 80s Sir Ralph’s son, another Ralph, continued the same process of family consolidation, hitching his political fortunes first to Lord Rockingham and then, on his death, to Charles James Fox. In 1790 after a ruinous campaign that is reckoned to have cost the family £15,000, he was finally returned in second place for Durham Co, and for the next twenty-two years remained its MP, a genial and ineffectual ‘Uncle Toby’ whose fidelity to the Whig cause, in his daughter’s succinct phrase, was ‘as little valued as doubted’.24

It was into this family and this world, on 17 May 1792, that Anne Isabella Milbanke was born. The future Lady Byron has always seemed to belong so completely to the nineteenth century that it is easy to forget that this is where her roots lie, that her moral and social being was shaped by the inherited virtues and limitations implicit in Stubbs’s painting or her family’s dilettante public service.

But if the young Annabella was brought up in a political milieu, behind the web of alliances and obligations that supported two generations in parliament lay realities of landed life that had a far more profound effect on her vision. From the middle of the seventeenth century the principal seat of the Milbankes had been Halnaby Hall, a red-bricked Jacobean manor house, now gone, that lay just off the Great North Road outside the village of Croft in Yorkshire. In the village church of St Peter’s a wonderfully grandiose tomb and pew still evoke the dynastic ambitions of the early Milbankes, but Annabella’s affections remained all her life with the modest estate at Seaham on the north-east coast where she grew up. ‘If in a small village’, she recalled many years later, in a passage that might have come from George Eliot,

you cannot go out of the gates without seeing the children of a few Families playing on the Green, till they become ‘familiar faces’, you need not be taught to care for their well-being. A heart must be hard indeed that could be indifferent to little Jenny’s having the Scarlet Fever, or to Johnny’s having lost his mother … I did not think property could be possessed by any other tenure than that of being at the service of those in need.25

The Milbankes and Seaham may have given Annabella a sense of the rooted interdependency of country life, but through her mother she could lay claim to a more exotic strain of English history. Judith Noel was born in 1751, the eldest daughter of Sir Edward Noel of Kirkby Mallory, first Viscount Wentworth and heir through the contorted female line to the sixteenth century Wentworth barony. It would be dangerous to describe any title that has survived with the tenacity of the Wentworths as ‘doomed’, but when a family branch can provide a Lancastrian standard-bearer at St Albans, a Governor of Calais under Mary Tudor, and the devoted mistress to the Duke of Monmouth, it is at least guilty of the kind of ill-luck that might pave the way to a marriage with Byron.

For someone so outwardly prosaic as Annabella, there was, too, a curiously vivid streak of romanticism that fed directly off her sense of history. In a self-portrait written as a woman of thirty-nine, she looked back on her childhood self, on a miniature Dorothea Brooke pulled backwards and forwards between the claims of the imagination and the stern imperatives of a protestant conscience. ‘Impressed from earliest childhood with a sense of duty, and sympathising with the great and noble in human character’, she wrote,

my aspirations went beyond the ordinary occasions of life – I wasted virtuous energy on a visionary scene, and conscience was in danger of becoming detached from that before me. Few of my pleasures were connected with realities – riding was the only one I can remember. When I climbed the rocks, or bounded over the sands with apparent delight, I was not myself. Perhaps I was shipwrecked or was trying to rescue other sufferers – some of my hours were spent in the Pass of Thermopylae, others with the Bishop of Marseilles in the midst of Pestilence, or with Howard in the cheerless dungeon …

About the age of 13… I began to throw my imagination into a home-sphere of action – to constrain myself, from religious principle, to attend to what was irksome, and to submit to what was irritating. I had great difficulties to surmount from the impetuosity and sensitiveness of my character … It was this stage of my character which prepared me to sympathise unboundedly with the morbidly susceptible – with those who felt themselves unknown …26

It would clearly be absurd to try to define her exclusively in terms of ancestry, but there is a sense in which the solidity of the Milbankes and the romanticism of the Wentworth inheritance combined to produce in Annabella something distinctly new, a kind of fierce ordinariness, a strident centrality that raised the commonplace to the realms of genius, orthodoxy to the stuff of crusade.

Along with this dual inheritance, the circumstances of her own contented upbringing can only have sharpened the feeling of singularity with which she coloured the most ordinary imaginative experiences of childhood. In the same Auto-Description she lamented a ‘want of comparison’ in her Seaham life that blinded her to the advantages of birth, and yet of greater importance than the inevitable isolation of a small Durham village was the simple fact that she was the only child of parents who had waited fifteen years for an heir.

Ralph Milbanke and Judith Noel had married in 1777, and although they had brought up a niece as if she was their own child, there is no mistaking the ferocious joy that greeted Anna-bella’s birth. It is often admiringly noted that she was encouraged in her opinions from her earliest days, but if her childhood self can be back derived from her adult character, hers was the kind of independence that might have flourished more safely in the face of opposition than indulgence, her character one that would have fared better outside the warmth and admiration of a family that placed her firmly and uncritically at its centre. ‘It was indeed Calantha’s misfortune to meet with too much kindness,’ her cousin Caroline Lamb wrote of herself in a passage in Glenarvon that throws an unexpected light on this – a passage that sufficiently stung Annabella when she read the novel to have her mark and angrily refute its psychology in a criticism that survives still among her papers,

or rather too much indulgence from all who surrounded her. The Duke, attentive solely to her health, watched her with the fondest solicitude, and the wildest wishes her fancy could invent, were heard with the most scrupulous attention, and gratified with the most unbounded compliance.27

This regime of indulgence was made more dangerous in Anna-bella’s case by an intelligence that in and outside the home had little to challenge it. Even as a child she was conscious of being cleverer than most of those around her, but it was a cleverness dangerously at the service of unchallengeable moral certitudes, an intelligence that seems never to have broadened with reading or turned on itself in any genuine spirit of criticism. From the evidence of her letters and journals there was certainly a kind of scrupulousness about her, and yet even here her scruples and self-doubts were, like her shyness, the self-referential workings of an imagination that ultimately appealed to no other judgement but its own.

If Annabella Milbanke had simply married as Milbankes had traditionally married, none of this might have much mattered, and it is likely that she would have done no more than add one more name to history’s forgotten roll of mute, inglorious husbands. From the earliest family descriptions one can glimpse the formidable chatelaine she should have been, but substitute the name Byron for that of George Eden or any of her earlier suitors, see that ten-year-old girl with the determined pout Hoppner painted as the future Lady Byron, and the warmth, the love, the privilege and security of her sheltered upbringing suddenly seem the laboratory conditions for breeding the disaster of the most notorious marriage in literary history.

It is the inevitable condition of biography to shape a life with the benefits of hindsight in this way, and yet it is only hindsight that casts a shadow over the prelapsarian happiness of Annabella’s childhood. In her own eyes the memories of Seaham would always have the poignancy of blighted innocence, but the horror is that it could have ever equipped anyone so essentially limited in experience or culture to imagine that she could understand or tame a Byron.

It is often forgotten, in the feeding frenzy that invariably accompanies her name, how vulnerably young she was when she first met him in 1812, and yet nothing suggests that another summer or two would have made the difference. She had come up to London for her first season in the previous year, and although there were suitors enough to satisfy anyone’s vanity, not even a future governor-general of India or Wellington’s adjutant general in the Peninsula had been sufficient to jolt her out of the complacent certainties of her Seaham world. ‘I met with one or two who, like myself, did not appear absorbed in the present scene’, she later wrote of this period,

and who interested me in a degree. I had a wish to find among men the character I had often imagined – but I found only parts of it. One gave proofs of worth, but had no sympathy for high aspirations – another seemed full of affection towards his family, and yet he valued the world. I was clear sighted in these cases – but I was to become blind.28

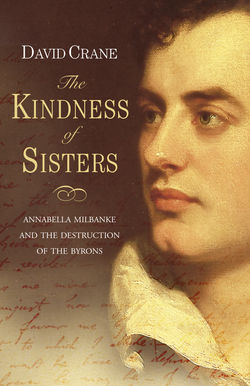

It was a misfortune, too, for a woman who could think like this to see her future husband for the first time in his annus mirabilis, because if there were far more interesting ‘Byrons’ than the triumphant author of Childe Harold, there was none more likely to appeal to a romantic moralist of Annabella’s stamp. ‘Lavater’s [the phrenologist] system never asserted its truth more forcibly than in Byron’s countenance’, the portrait painter Sir Thomas Lawrence wrote at the height of Byron’s fame, wonderfully capturing the mix of glamour and threat in the figure that seduced London’s ‘golden parallelogram’ in the spring and summer of 1812,

in which you see all the character: its ken and rapid genius, its pale intelligence, its profligacy, and its bitterness; its original symmetry distorted by the passions, his laugh of mingled merriment and scorn; the forehead clear and open, the brow boldly prominent, the eyes bright and dissimilar, the nose finely cut, and the nostril acutely formed; the mouth well made but wide and contemptuous even in its smile, falling singularly at the corners, and its vindictive and disdainful expression heightened by the massive firmness of the chin, which springs at once from the centre of the full under-lip; the hair dark and curling but irregular in its growth; all this presents to you the poet and the man; and the general effect is heightened by a thin spare form, and, as you may have heard, by a deformity of limb.’29

Byron was just twenty-four when, after more than two years’ travel across Europe and the east, the sudden and unprecedented success of Childe Harold changed his life and the course of Romantic literature. He had already produced some feeble juvenilia and a long and scabrous satire he had since come to regret, but nothing in his literary or private life, nothing in the intense and homoerotic friendships of his Harrow and Cambridge days or the bisexual philandering in the Levant had prepared him emotionally for the loneliness of fame that swamped him on his return, a poet without conviction, an aristocrat without a sense of belonging, a liberal without the stamina or will for political life, an icon with a morbid sensitivity to his lameness.

It would have been odd in fact if Annabella alone had not felt drawn to Byron that summer, and yet even in the privacy of her diary and letters she felt she owed her intelligence some more refined expression of her feelings than the general excitement that gripped Regency society. She had first seen him at a morning waltzing party given by Caroline Lamb on 25 March, and after filling her journal that night with her impressions, the next day reported back to her mother in Seaham. ‘My curiosity was much gratified by seeing Lord Byron, the object at present of universal attention’, she wrote,

Lady Caroline has of course seized on him, notwithstanding the reluctance he manifests to be shackled by her … It is said that he is an infidel, and I think it probable from the general character of his mind. His poem sufficiently proves that he can feel nobly, but he has discouraged his own goodness. His features are well formed – his upper lip is drawn towards the nose with an expression of impatient disgust. His eye is restlessly thoughtful. He talks much, and I heard some of his conversation, which is very able, and sounds like the true sentiments of the Speaker.

I did not seek an introduction myself, for all the women were absurdly courting him, and trying to deserve the lash of his satire. I thought that inoffensiveness was the most secure conduct, as I am not desirous of a place in his lays. Besides, I cannot worship talents that are unconnected with the love of man, nor be captivated by that Genius which is barren in blessings – so I made no offering at the shrine of Childe Harold, though I shall not refuse the acquaintance if it comes.30

The acquaintance finally came the next month at a party of Lady Cowper’s, and with it the note of ironic detachment became increasingly hard to sustain. In her letters home to her mother she continued to insist that ‘calm benevolence’31 alone could touch her heart, but no amount of dissembling to her parents or herself could disguise the fact that curiosity was rapidly turning into the crusade that would shape her whole life. ‘Do you think there is one person here who dares to look into himself?’, she later recalled the question that had inspired her first mute ‘offering’ at the shrine of Childe Harold,

… I felt that he was the most attractive person; but I was not bound to him by any strong feeling of sympathy till he uttered these words, not to me, but in my hearing – ‘I have not a friend in the world!’ It is said that there is an instinct in the human heart which attaches us to the friendless. I did not pause – there was my error to enquire why he was friendless; but I vowed in secret to be a devoted friend to this lone being.32

There is something unsettling in the reveries of the young Anna-bella, or at least in her incapacity to see them for what they were. The descriptions of Byron that litter her diary and letters are as banal as those of anyone else that season, but running through them is that old and dangerous sense of election, the conviction of some private and silent understanding that set her apart in a city swept along on the rhythms of the waltz and the voyeuristic thrill of Caroline Lamb’s pursuit of Byron.

If there was nobody to blame for these delusions but Annabella, however, it is clear that she had not just imagined Byron’s interest in her. In the wreck of their marriage she once accused him of only ever wanting what he could not have, but if there is something in that, the more brutal truth is that he simply could not see her for what she was – could not see the provinciality that passed for independence, the rigidity latent in her strength, the narrowness which, with the nostalgia of the jaded sophisticate, he wistfully put down to moral superiority. ‘I set you down as the most puzzling person there’, he later told her of the first time he had seen her, across a room full of morning-visitors at Melbourne House,

For there was a quiet contempt of all around you & the nothings they were saying & doing in your manner that was so much after my own heart. There was a simplicity – an innocence – a beauty in your deportment & appearance which although you hardly spoke – told me I was in company with no common being.33

As the spring of 1812 wore on, and Byron’s life drifted dangerously and publicly into the chaos of his notorious affair with Caroline Lamb, it was not so much what Annabella was as what she was not that attracted Byron. The kinds of virtues and solidity with which he invested her would always hold a theoretical attraction for him, but it is hardly an exaggeration to say that if there had been no Caroline Lamb to escape then there would have been no marriage to her cousin, Annabella.

Byron had first come across Caro Lamb, the twenty-seven-year-old, fragile, androgynous-looking child wife of William Lamb, when she had written to him under a thin veil of anonymity after the triumph of Childe Harold in February 1812. Even before she had set eyes on him she had declared that she would know its author if he was ‘as ugly as Aesop’34, and within weeks of meeting she had made sure their affair was public property, played out with a kind of arriviste relish on his part and on hers with a reckless exhibitionism hovering on the edge of insanity.

There is not a moment of an affair that defined and caricatured the Romantic passion in all its delinquent intensity that has not been raked over a hundred times, but in the context of his relationship with Annabella it still has its place here. In later years Byron came to hate Caroline with a passion that only Claire Clairmont could otherwise inspire, but in its first weeks at least what attracted him to the maddest of all the Spencers was precisely the wayward and uncontrollable element in her that he eventually came to loathe.

There was a wonderfully sane and balanced side to Byron that would always in the end tire of romantic excess, and yet after the initial excitement had passed something more than boredom turned him against Caroline Lamb. An illicit element to some of his earlier, male relationships had sometimes unnerved him, but as he tried to distance himself from Caroline he found himself contending with a woman ready to call the Childe’s bluff, to live out the implications of his Romanticism with a patrician contempt for convention that in his first year of success he had neither the courage nor the confidence of ‘belonging’ to match.

Even with the contrast of Caroline Lamb to concentrate his mind, it is unlikely that his interest in Annabella would ever have quickened into anything more important had it not been for the intervention of her aunt (Caroline Lamb’s mother-in-law), Lady Melbourne. By the time that Annabella made her London debut, the girl in Stubbs’s portrait had reigned as the‘spider queen’ of Whig society for over a generation, ‘a sort of modern Aspasia’ with the brain and morals to match, tolerant, attractive, intelligent, cynical, corrupt and – to Byron at least – ‘the best, the kindest, and ablest female I have ever known, old or young’. ‘She was a charming person’, he later told Lady Blessington,

uniting the energy of a man’s mind with the delicacy and tenderness of a woman’s. She had all of philosophy, save its moroseness, and all of nature, save its defects and general faiblesse … I have often thought, that, with a little more youth Lady M. might have turned my head, at all events she often turned my heart, by bringing me back to mild feelings, when the demon passion was strong within me. Her mind and heart were as fresh as if only sixteen summers had flown over her, instead of four times that number – and the mind and heart always leave external marks of their state of health. Goodness is the best cosmetic that has yet been discovered … She was a captivating creature, malgre her eleven or twelve lustres, and I shall always love her.35

Even in her early sixties, the ‘spider’ or the ‘thorn’ still retained the power, desire and intelligence that had once made her the mistress of Lord Egremont and the Prince of Wales. As a young bride she had been forced to stand and watch her husband’s ludicrous pursuit of the actress Sophia Baddeley, but with the ambition and purpose Stubbs caught so well, disappointment had simply deflected her energies into the ruthless pursuit of family influence that was to consume the rest of her life. ‘The charms of her person and the endowments of her mind were worthy of a better fate than that she was preparing for herself’, Caroline Lamb wrote savagely of her in Glenarvon, the roman à clef with which she took her revenge not just on Byron but on the Whig world that had turned its back on her,

But, under the semblance of youthful gaiety, she concealed a dark intriguing spirit, which could neither remain at rest, nor satisfy itself in the pursuit of great and noble objects. She had been hurried on by the evil activity of her own mind, until the habit of crime had overcome every scruple, and rendered her insensible to repentance, and almost to remorse. In this career she had improved to such a degree her natural talent of dissimulation, that, under its impenetrable veil, she was able to carry on securely her darkest machinations; and her understanding had so adapted itself to her passion, that it was in her power to give, in her own eyes, a character of grandeur, to the vice and malignity, which afforded an inexplicable delight to her depraved imagination.36

With daughter and mother-in-law both living in Melbourne House, a delicate balancing act was required, but from the moment Byron tried to extricate himself from the affair with Caroline, he found Lady Melbourne a subtle and determined ally. To a woman who had charmed and slept her way to the top of Whig society, her daughter-in-law’s morals were of no great concern, but the one crime the lax Regency world would not forgive was indiscretion and as Caroline’s antics began to threaten the dynastic ambitions ‘the spider’ held for her family, Lady Melbourne moved to neutralise her.

In spite of all her cynicism, though, it can no more have occurred to Lady Melbourne than it had to Byron that the solution to their mutual problem lay in her cool, self-contained country niece. For their different reasons both Caroline Lamb and her sister-in-law ‘Caro George’ had done their best to convince him that Annabella was already engaged, but he had hardly needed their warnings to keep a wary distance from a woman he instinctively recognised as his opposite. ‘My dear Lady Caroline’, he had written as early as 1 May, after reading some verses of Annabella’s,

I have read over the few poems of Miss Milbank with attention. – They display fancy, feeling, & a little practice would very soon induce facility of expression … She certainly is a very extraordinary girl, who would imagine so much strength & variety of thought under that placid countenance? You will say as much of this to Miss M. as you think proper. – I say all this very sincerely, I have no desire to be better acquainted with Miss Milbank, she is too good for a fallen spirit to know or wish to know, & I should like her more if she were less perfect.37

There is no reason to doubt Byron – Annabella is not mentioned in his letters for more than four months – but the idea of her had taken a dogged hold of his imagination. There was no pretence on his part that he was in love with her, or anyone else, but as over July and August the pressure from both the Lambs and Caroline’s mother to end the affair grew, he was faced with the fundamental need of the outsider to assimilate or face destruction. ‘I see nothing but marriage & a speedy one can save me’, he wrote to Lady Melbourne on 28 September,

if your niece is attainable I should prefer her – if not – the very first woman who does not look as if she would spit in my face.38

‘You ask “if I am sure of myself”’ he had already written to Lady Melbourne ten days earlier, after first hesitantly broaching the idea of Annabella to her in a letter from Cheltenham on the 13th,

I answer – no – but you are, which I take to be a much better thing. Miss M. I admire because she is a clever woman, an amiable woman & of high blood, for I still have a few Norman & Scotch inherited prejudices on the last score, were I to marry. As to Love, that is done in a week (provided the Lady has a reasonable share) besides marriage goes on better with esteem & confidence than romance, & she is quite pretty enough to be loved by her husband, without being so glaringly beautiful as to attract too many rivals.39

At the beginning of October Lady Melbourne approached her niece on his behalf, and on the 12th received Annabella’s refusal from Richmond, complete with a ‘Character’ of Byron explaining her decision. ‘The passions have been his guide from childhood,’ she wrote, up on her ‘high stilts’ as her aunt described her,

and have exercised a tyrannical power over his very superior intellect. Yet among his dispositions are many which deserve to be associated with Christian principles – his love of goodness in its chastest form, and his abhorrence of all that degrades human nature, prove the uncorrupted purity of his moral sense.

There is a chivalrous generosity in his ideas of love and friendship, and selfishness is totally absent from his character. In secret he is the zealous friend of all human feelings; but from the strangest perversion that pride ever created, he endeavours to disguise the best points of his character. When indignation takes possession of his mind – and it is easily excited – his disposition becomes malevolent. He hates with the bitterest contempt; but as soon as he has indulged those feelings, he regains the humanity which he had lost – from the immediate impulse of provocation – and repents deeply.40

It is difficult to be sure of Byron’s real feelings at this rejection, or even whether he knew himself, but whatever they were he would never have dropped the tone of cool worldliness with Lady Melbourne that had become their common language. ‘Cut her! My dear Ly. M. marry – Mahomet forbid!’ – he wrote to her on receiving the news, anxious to allay any suspicion of resentment,

I am sure we will be better friends than before & if I am not embarrassed by all this I cannot see for the soul of me why she should – assure her con tutto rispetto that The subject shall never be renewed in any shape whatever, & assure yourself my carissima (not Zia what then shall it be? Chuse your own name) that were it not for this embarras with C I would much rather remain as I am. – I have had so very little intercourse with the fair Philosopher that if when we meet I should endeavour to improve our acquaintance she must not mistake me, & assure her I never shall mistake her … She is perfectly right in every point of view, & during the slight suspense I felt something very like remorse for sundry reasons not at all connected with C nor with any occurrence since I knew you or her or hers; finding I must marry however on that score, I should have preferred a woman of birth & talents, but such a woman was not at all to blame for not preferring me; my heart never had an opportunity of being much interested in the business, further than that I should have very much liked to be your relation. – And now to conclude like Ld. Foppington, “I have lost a thousand women in my time but never had the ill manners to quarrel with them for such a trifle.”41

The address on this letter – Cheltenham again – suggests, though, that Byron’s good humour was not simply feigned for Lady Melbourne’s benefit. He had gone to the fashionable spa town for the waters earlier in the summer, but long after it had been abandoned by most of London society he was still there, held by a growing fascination with that other ‘Aspasia’ of Regency England that he would have been reluctant to admit to Lady Melbourne, the beautiful, serially faithless forty-year-old Countess of Oxford, Jane Harley.

There is as much pseudo-psychological nonsense talked of Byron’s predilection for older women – as if everyone over the age of thirty were somehow identical – as there is over his fastidious distaste at the sight of a woman eating.* In the wake of Childe Harold it was inevitable that he should gravitate towards the great hostesses who dominated Whig society, but among even that disparate group it would be hard to imagine two women with less in common than Lady Melbourne and Lady Oxford, the one all caution, cynicism, and dynastic ambition, the other generous, impulsive, radical and careless of the proprieties she had so successfully defied from the first loveless years of marriage.

The daughter of a clergyman, Jane Scott had been born in Inchin, and at the age of twenty-two ‘sacrificed’, as Byron later told Medwin, ‘to one whose mind and body were equally contemptible in the scale of creation’43. If Lord Oxford had never been much of a match for his dazzling and ambitious wife, however, he was no gaoler either, and by the time that she began her affair with Byron the ‘grande horizontale’ of Whig political radicalism was already the mother of five children by as many fathers, ‘a tarnished siren of uncertain age’, as Lord David Cecil described her with patrician distaste,

who pursued a life of promiscuous amours on the fringe of society, in an atmosphere of tawdry eroticism and tawdrier culture. Reclining on a sofa, with ringlets disposed about her neck in seductive disarray, she would rhapsodise to her lovers on the beauties of Pindar and the hypocrisy of the world.44

Byron had first met her during the London season, but it was at Cheltenham and then at Eywood, the Oxfords’ country house in Herefordshire, that their friendship developed into the infatuation that absorbed him for the next six months. ‘She resembled a landscape by Claude Lorraine’, Lady Blessington – no ingenue herself – recalled him saying,

‘with a setting sun, her beauties enhanced by the knowledge that they were shedding their last dying beams, which threw a radiance around. A woman (continued Byron) is only grateful for her first and last conquest. The first of poor dear Lady [Oxford’s] was achieved before I entered on this world of care, but the last I do flatter myself was reserved for me, and a bonne bouche it was.’45

It is impossible to imagine Byron speaking of Lady Melbourne in this tone, but if Lady Oxford never exerted the same dominance over him as the ‘spider’ had done, in the sensual and intellectual licence of the ‘bowers of Armida’46, as he labelled Eywood, he found a retreat from any fleeting disappointment at Annabella’s rejection and the continuing assaults of Caroline Lamb. ‘I mean (entre nous my dear Machiavel)’, he had written to Lady Melbourne,

to play off Ly. O against her, who would have no objection perchance but she dreads her scenes and has asked me not to mention that we have met to C or that I am going to E.47

‘I am no longer your lover’, he wrote to Caroline herself, as good as his word, if the letter she reproduced in Glenarvon is the faithful copy of Byron’s that she claimed it to be,

and since you oblige me to confess it, by this truly unfeminine persecution, – learn, that I am attached to another; whose name it would of course be dishonorable to mention. I shall ever remember with gratitude the predilection you have shewn in my favor. I shall ever continue as your friend, if your ladyship will permit me so to style myself; and as a first proof of my regard, I offer you this advice, correct your vanity, which is ridiculous; exert your absurd caprices upon others; and leave me in peace.48

In spite of the callousness of this letter – a cruelty that forms the counterpart to Byron’s generosity – his relationship with Caroline had stirred him in ways that Lady Oxford never did. There is no disguising the sense of almost bloated content that runs through many of Byron’s letters from Eywood, and yet at some level both he and Lady Oxford knew that the demons that drove him were not ones that could be contained within Armida’s bowers or the boundaries of Whig politics she had marked out for him.

For all the sexual and intellectual freedom Byron enjoyed at Eywood, the affair with Lady Oxford was too tame ever fully to satisfy him. In all his most important relationships there had been an element of risk and social danger, but there was something almost institutional in the sexual abandon of Lady Oxford, a kind of licensed immorality that paradoxically took Byron closer to one branch of the Whig political establishment than he had ever been before.

And there was never a time, either, when Byron was more dangerous than when made aware of how little he wanted what English society had to offer him. ‘I am going abroad again’, he announced in March 1813, in the middle of his affair with Lady Oxford,

… my parliamentary schemes are not much to my taste – I spoke twice last Session – & was told it was well enough – but I hate the thing altogether – & have no intention to ‘strut another hour’ on that stage.49

Byron was being partly disingenuous – for all the kind words that greeted his debut speech it had only had a limited impact – but his suppressed unease of this period was more than a defensive reflex to disappointment. It is clear from his own comments that he knew that he would never make a parliamentary orator, and yet it is hard to believe that success could any more have reconciled the creator of Childe Harold – still less the ‘Titan battling with religion and virtue’50 that Nietzsche admired in Byron – to the limitations of English public life and a career in politics.

If it seems inevitable that the young Nietzsche should be drawn to Byron – and in particular to the creator of the defiant Manfred – the quality that he most admired in him was the courage to follow his instincts that Lawrence also saw as the defining characteristic of the ‘aristocrat’. In his Hardy essay Lawrence wrote that ‘the final aim of every living thing … is the full achievement of itself’51, but as Byron’s affair with Lady Oxford guttered towards its untidy end, it was precisely that goal of self-realisation – the supreme ambition of the Romantic imagination – that he recognised with an ever increasing clarity he could never achieve in England.

In an age that is as ready to recognise the tyranny of sex as ours is, it is possibly enough to point out that for a man of Byron’s sexual ambivalence a country that still sent homosexuals to the gallows was no place to be. From the publication of the spurious ‘Don Leon’ poems in the mid-nineteenth century, Byron has always been an icon and spokesman for homosexual freedom, and yet the vital thing in this context is not so much the question of his sexual identity per se – who now cares? – but the wider issues of creative fulfilment or frustration with which it was inevitably and intimately bound.

For Byron, as for Lawrence, the test of ‘being’ was ‘doing’, and as the year dragged on he was conscious of how little he had achieved as a poet. For all his aristocratic disdain for the business of versifying he was keenly aware that he had ‘something within that “passeth show”’52, and yet for a man whose lameness, childhood and sexual ambiguities all supremely equipped him to challenge political, moral, or physical injustice in every form he found it, he had precious little to show. The adolescent anger of English Bards and Scotch Reviewers, which he had long since repudiated? The stagey and harmless posturing of Childe Harold? A clutch of cautiously disguised tributes to the dead Cambridge chorister, Edleston? ‘At five-and-twenty, when the better part of life is over’, he wrote in his journal,

one should be something; – and what am I? nothing but five-and-twenty – and the odd months.53

But if, in these early months of 1813, Byron still lacked what Lawrence called the ‘courage to let go the security, and to be54’, this sense of self-dissatisfaction and estrangement was gradually pushing him towards a crisis. As early as May he was writing to Lady Melbourne of the need to escape a world that was stifling him, and at the end of June he returned with increased irritation to the same theme. ‘I am doing all I can to be ready to go with your Russian’ [Prince Koslovsky, a visiting Russian diplomat], he told her,

depend upon it I shall be either out of the country or nothing – very soon – all I like is now gone – & all I abhor (with some few exceptions ) remains – viz – the R[egent] – his government – & most of his subjects – what a fool I was to come back – I shall be wiser next time.55

It is a curious, if somehow irrelevant, thought that Byron might have gone abroad in the summer of 1813, either with the Oxfords to Sicily as was planned at one time, or farther east to the Levant. Byron himself had such a strong sense of his own destiny that even with the benefit of hindsight it is hard to see his life in any other shape than that which it finally took, and if this ignores those elements of chance and sloth that right up to his death might have disposed of him in a dozen different ways, one only has to picture him for a moment harmlessly cruising the Mediterranean to recognise the inherent implausibility of the vision.

Because if Byron was to grow as a man or a poet, he did not need simply to escape England, but to smash with a complete and final violence everything that held him to it. In his relationship with Caroline Lamb during the previous year he had come dangerously close to doing this, and while he had pulled back from the edge then it was only a matter of time before he recognised that the conformist elements in his nature could never be squared with the vocation for opposition he claimed as the Byron birthright.

‘I have no choice’ – Byron put the words in Manfred’s mouth – and it is this sense of necessity that attracted both Lawrence and Nietzsche to the dramatic parabola of Byron’s life and career. There is of course a world of difference between the Lawrentian ‘aristocrat’ and the iibermensch that Nietzsche hailed in the figure of Manfred. Yet if Lawrence’s ultimate concern was with fulfilment in the deepest and most human sense of the word, he never shirked the fact that for an outsider of Byron’s stamp that inevitably meant war. ‘This is the tragedy’, Lawrence wrote,

… that the convention of the community is a prison to his natural, individual desire, a desire that compels him, whether he feels justified or not, to break the bounds of the community, lands him outside the pale, there to stand alone, and say: ‘I was right, my desire was real and inevitable; if I was to be myself I must fulfil it, convention or no convention …’56

It is this sense of inevitability that gives the air of a ‘phoney war’ to the period of Byron’s affair with Lady Oxford. When at the end of June she left England with her husband he confessed that he felt more ‘Carolinish’57 about it than he had expected, despite the fact that for all her attractions she could no more satisfy him than Caroline Lamb herself had done before her.

Still less could one of the great regnantes of Whig society answer his need for a rupture with everything that held him to England. It did not, though, matter. By the time that Lady Oxford finally sailed, on 28 June, the one woman had re-appeared in his life who could fill both roles: a woman who by her birth and temperament was not only uniquely placed to define the full nature of Byronic rebellion but also to meet with a peculiar psychological and emotional fitness what Lawrence called ‘the deepest desire’ of life,

a desire for consummation … a desire for completeness, that completeness of being which will give completeness of satisfaction and completeness of utterance.58

The woman in question was the Hon. Mrs Augusta Leigh, the twenty-nine-year-old daughter of Byron’s father by his first, scandalous, marriage to Amelia Darcy, Baroness Conyers in her own right and the wife of the heir to the Duke of Leeds, the Marquess of Carmarthen.

The son of that famous sailor and womaniser, ‘Foulweather Jack’, ‘Mad Jack’ Byron seemed ‘born for his own ruin, and that of the other sex.’59 Six years before Augusta’s birth, the dazzling and wealthy Marchioness had met and fallen for him, picnicked with him one day and abandoned her husband for him the next, living defiantly with him in a ‘vortex of dissipation’60 until a well-publicised divorce left her free to marry him and move to France.

Whatever fondness his son might retain for his memory, ‘Mad Jack’ was as callous a rake as eighteenth-century gossip portrayed him, with all the Byron charm and none of its generosity. For five years he lived off his wife’s fortune in either Chantilly or Paris, but when shortly after Augusta’s birth he lost wife and income together, Jack Byron abandoned the child to the first in a long succession of guardians and relatives, and set off on the predatory hunt for another heiress that finally led to Bath and Catherine Gordon.

For a few months, as a four-year-old, Augusta lived with her father and his pregnant new wife at Chantilly, but from the moment she was handed over to her grandmother, Lady Holderness, she left behind the depravation and uncertainty that was Jack Byron’s only obvious legacy to his children. During the crucial years when Catherine Gordon and her son were struggling under the indignities of poverty and isolation, the orphaned Augusta was growing up among a clutch of aristocratic relations into a tall and graceful girl, ‘light as a feather’, with a long, slender neck and heavy mass of light brown hair, a fine complexion, large mouth, retroussé nose, beautiful eyes, gentle manner, and a pathological shyness that eclipsed even that of her unknown Byron half-brother.61

If these formative years among her Howard cousins and the half-brothers and sisters of her mother’s first marriage gave Augusta an uncritical, aristocratic ease that Byron never matched, as a grounding in emotional subservience they had more corrosive consequences. There was a fundamental docility to her character that probably ran deeper than any social conditioning, but for a girl of such natural reticence and limited prospects, a childhood of gilded dependence in the great houses of her relations can only have compounded the instinct for self-surrender that was to mark her adult life.

It was an instinct confirmed, too, when after a six-year courtship she finally married her feckless cousin, George Leigh, and sank into a life of straitened domesticity from which she never escaped. Colonel George Leigh has always had one of those roles in the Byron story that never quite swells even to a walk-on part, but for his wife at least he was real enough, an irascible and incapable husband and father in equal measure, a cavalry officer whose career ended in financial scandal and a gambler whose sharpness, even in the world of Newmarket and the circles of the Prince of Wales, placed him on the wrong side of social acceptability.

It can seem at times as though Augusta only existed in and through other people, so it is little wonder that a woman with such a genius for self-effacement has always proved hard to pin down. From the first day that her character was dragged into the public domain it has been open season on her, but after a hundred and fifty years of legal and biographical prodding she remains as elusive and unknowable as ever, leaving behind only a kind of erotic charge that is as close as we can get to her, an impression of femininity so endlessly and placidly accommodating as to obliterate all individuality.

A ‘fieldsman’, Thomas Hardy wrote in Tess, is never anything more than a man in a field but a woman is continuous with the natural world, and something of that universality clings to the finest surviving image we have of Augusta Leigh. There is little contemporary evidence to suggest she ever looked like Hayter’s lovely drawing of her, but in the languor and passivity of that face, the tilt of the head and the long curve of the neck, he has surely left us the essential Augusta – the ‘sleepy Venus’ of Byron’s Don Juan, the Zuleika of The Bride of Abydos, the mother of seven children by a husband she hardly ever saw – the woman whose idle and easy sexuality could disturb and attract both men and women every bit as much as her half-brother’s flagrant aggression.

Augusta had first met Byron when she was a girl of seventeen and he an awkward and overweight schoolboy of thirteen. From their first exchanges of letters the two were natural allies in his endless battles with his mother, but in spite of a protective – and on his side almost seigneurial – affection they saw very little of each other as children. At the age of seventeen Augusta was already infatuated with her Leigh cousin, and as Byron himself moved from Harrow to Cambridge and then on to his travels in the east she inevitably became more of an idea than a reality to him.

In the long run there could have been nothing more dangerous than this legacy of intimacy and distance, and no more vulnerable time for Augusta to re-enter his life than the summer of 1813, when his affair with Lady Oxford was petering out and Caroline Lamb was taking her last melodramatic revenge. The correspondence between Byron and Augusta for the preceding months is missing, but it seems almost certainly his idea that she should come up to London. She had written to him the previous January in need of money to meet her husband’s gambling debts, and although financial troubles over Newstead left Byron in no position to help, his answer emphasises the sad hollowness she alone would fill. The ‘estate is still on my hands’, he began a long list of complaints, ‘& your brother not less embarrassed …

I have but one relative & her I never see – I have no connections to domesticate with & for marriage I have neither the talent nor the inclination – I cannot fortune-hunt nor afford to marry without a fortune … I am thus wasting the best part of my life daily repenting and never amending … I am very well in health – but not happy nor even comfortable – but I will not bore you with complaints – I am a fool & deserve all the ills I have met or may meet with.62

There was something prophetic in that last line, because almost from the moment she arrived in London, Byron seems to have been bent on disaster. If ‘form’ is anything to go by, he would inevitably have turned to someone on the rebound from Caroline and Lady Oxford, but if anyone might have done, Augusta seemed to offer everything, the excitement of novelty and the comfort of familiarity, the danger of the forbidden with the guarantee of safety implicit in her name.

Because above all she was a Byron, and for someone so self-absorbed and yet utterly lacking in self-love as her brother that was an irresistible attraction. In the years since their childhoods he had formed some of the most intense friendships of his life, but it was only with a more attractive version of himself, as he now saw Augusta, a woman with so many of the same mannerisms and the same shyness, that he found his deepest, almost platonic desire for completion realised. ‘For thee, my own sweet sister’, he addressed her,

in thy heart

I know myself secure, as thou in mine;

We were and are – I am, even as thou art –

Beings who ne’er each other can resign;

It is the same, together or apart,

From life’s commencement to its slow decline

We are entwined – let death come slow or fast,

The tie which bound the first endures the last!63

With her endless good-humour and sense of fun, her charm and talent for nonsense – her ‘damn’d crinkum-crankum’64 as he called it – Augusta also represented a simple release from the tensions of London life. Almost immediately she became an integral part of his routines, included in his invitations and plans, the novel half of a double-act that was part spontaneous and part calculation. ‘If you like to go with me to ye. Lady Davy’s tonight’, he wrote in a note that nicely captures the blend of pride and vanity with which he looked on her,

I have an invitation for you – There will be the Stael – some people whom you know – & me whom you do not know & you can talk to which you please – & I will watch over you as if you were unmarried & in danger of always being so … I think our being together before 3d. people will be a new sensation to both.65

With anyone except Augusta this might have led nowhere, but with her chronic habit of subservience, it was only a matter of time before affection and familiarity slid into something more perilous. It is impossible to know with any absolute certainty when brother and sister became lovers, but if the malicious gossip of Caroline Lamb – or Byron’s own boast to Tom Moore that her seduction had cost him little trouble – has any substance it was probably only a matter of weeks or even days.

The mere use of the word ‘seduction’ in this context however – Byron at his coarsest – wilfully trivialises and misrepresents a relationship that he would always more honestly recognise as the most important of his life. If these things can ever be judged from the outside, it would seem that sex was always of secondary significance in their affair, on Augusta’s side to a limitless capacity for self-surrender, and on Byron’s to the expression of a kindness and generosity that was at the core of his personality.

And yet when that is said, his letters and verse make it clear that he inspired in the twenty-nine-year-old mother of three a passion that surprised them both with its violence and abandon. In the best known celebrations of their love it is always a platonic ideal of union that Byron is anxious to stress, but in Zuleika’s language in The Bride of Abydos we are almost certainly taken closer to the earthier reality of its early days. ‘To see thee, hear thee, near thee stay,’ Zuleika tells the man she believes to be her brother, in a passage which unconsciously echoes the startled self-discovery of Shakespeare’s Perdita in the great fourth act of A Winter’s Tale

And hate the night I know not why,

Save that we meet not but by day,

With thee to live, with thee to die,

I dare not my hope deny:

Thy cheek, thine eyes, thy lips to kiss,

Like this – and this – no more than this;

For, Allah! Sure thy lips are flame:

What fever in thy veins is flushing?

My own have nearly caught the same,

At least I feel my cheek, too, blushing.66

Even when this is recognised, however, the seamless, almost inevitable transition from sister to lover was for Augusta only one stage in a more complete annihilation of self. ‘Partager tous vos sentiments,’ she wrote to him in November 1813, enclosing with the note a lock of her hair: ‘Ne voir que par vos yeux’ – ‘to share in your feelings, to see only with your eyes, to act only on your advice, to live only for you, that is my only desire, my plan, the only destiny that could make me happy.’67 ‘To soothe thy sickness,’ Zuleika continues in the same vein in the Bride,

watch thy health,

Partake, but never waste thy wealth,

Or stand with smiles unmurmuring by,

And lighten half thy poverty;

Do all but close thy dying eye,

For that I could not live to try;

For these alone my thoughts aspire:

More can I do, or thou require?68

The tragedy for Augusta, however, was that Byron did require more, because for him the affair was more complex and guilt-ridden than her simple devotion could comprehend. In reckless moments he might publicly ridicule the moral parochialism of an incest taboo, but at other times it could disturb him with a fear that stopped him naming Augusta even in the privacy of his journal. ‘Dear sacred name, rest ever unreveal’d,’ he quoted from Pope’s Eloisa in his November 1813 journal, adding his own gloss: ‘At least even here, my hand would tremble to write it.’69

Somewhere behind this fear lies the legacy of his Calvinist childhood, and yet as his deathbed shows, Byron was too intellectually and morally courageous to be cowed by the demons of the ‘Scotch School’. Throughout his life he habitually dramatised himself in terms of Miltonic defiance, but for all the swagger of Cain or Heaven and Earth, Byron’s sense of sin and exclusion was ultimately bound by this world rather than the next, his instinct for rebellion against man and not against God.

And this is perhaps the key to his behaviour with Augusta, because the fear he had of what they had done was less to do with a theological sense of sin than the growing recognition that he was prepared to push his defiance of convention to any limits. In his affair with Caroline Lamb the previous year, the courage or recklessness had seemed almost exclusively hers, but as he paraded Augusta in London and followed her to Newmarket and talked of exile together, as he trailed the affair in his letters and flaunted their incest in his poetry – as he pitted the Byrons against the world in the most public and symbolic way he could find – he discovered in Augusta not just his ideal refuge but his perfect weapon.

It would take the imaginative sympathy of a novelist to do justice to the complex and contradictory rhythms of Byron’s life as it slid towards open rupture with the society that had embraced him only eighteen months earlier. If one simply believed the evidence of his journal for the winter of 1813–14, the frustrations of the previous year were as acute as ever, but as one turns from that to his verse, the contrasting boldness of the poetry suggests rather an artist and man growing into a defiant sense of his own power and vocation.

In the space of a few days in November 1813 he wrote The Bride of Abydos, and the following month, in another spasm of creative energy, threw off the third of his Eastern tales, The Corsair. In his letters and journals he was as dismissive as one would expect of these achievements, and yet no amount of Byronic self-mockery or defensive irony could deflect the central importance these poems had for him.

The Bride of Abydos, written with Augusta and the theme of incest constantly in mind, had been, in his own words, his first ‘complete’ poem but in its own harsher way The Corsair was every bit as subversive. He had written the Bride in the first place to keep himself sane, but with its violent and antisocial rage The Corsair was in itself a kind of deliberate public madness, brilliantly conceived simultaneously to alienate and seduce his public. ‘Fear’d, shunn’d, belied, ere youth had lost her force,’ Byron described his hero whom he must have known by now his readers would associate with himself.

He hated man too much to feel remorse,

And thought the voice of wrath a sacred call,

To pay the injuries of some on all.

He knew himself a villain – but he deem’d

The rest no better than the thing he seem’d;

And scorn’d the best as hypocrites who hid

Those deeds the bolder spirits plainly did.

He knew himself detested, but he knew

The hearts that loath’d him, crouch’d and dreaded too.

Lone, wild, and strange, he stood alike exempt

From all affection and from all contempt:

His name could sadden, and his acts surprise;

But they that fear’d him dared not to despise:

Man spurns the worm, but pauses ere he wake

The slumbering venom of the folded snake:

The first may turn, but not avenge the blow;

The last expires, but leaves no living foe;

Fast to the doom’d offender’s form it clings,

And he may crush – not conquer – still it stings!70

‘I have just finished the Corsair – am in the greatest admiration’, Annabella Milbanke, wilting forgotten in the wings since her rejection of Byron’s proposal, wrote to Lady Melbourne,

In knowledge of the human heart & its most secret workings surely he may without exaggeration be compared to Shakespeare. He gives such wonderful life & individuality to character that from that cause, as well as from unjust prepossessions of his own disposition, the idea that he represents himself in his heroes may be partly accounted for. It is difficult to believe that he could have known these beings so thoroughly but from introspection … I am afraid the compliment to his poetry will not repay him for the injury to his character.71

For a brief period in the autumn of 1813 – probably to placate Lady Melbourne – Byron did his best to draw back from the edge with his pursuit of the young, newly married Lady Frances Webster, but by the end of the year Augusta was pregnant with a child which the dates suggested might well be his. In the middle of the following January, with a crisis mounting, brother and sister drove north to Newstead, ‘through more snows than ever opposed the Emperor’s retreat.’ Once arrived, there was no possibility of leaving. The roads beyond the Abbey were impassable, but their coals were excellent, he told his publisher, John Murray, the fireplaces large, the cellar full, his head empty, his only desire ‘to shut my doors & let my beard grow.’72

For the moment, defiance and refuge were in perfect equilibrium. ‘Never was such weather’, Byron wrote contentedly after ten days, ‘one would imagine Heaven wanted to raise a Powder-tax & had sent the snow to lay it on.’73 Never had his ancestral home seemed so all-sufficient as with Augusta. ‘And what unto them is the world beside,’ Byron later demanded in Parisina, his drama of incest and family doom that echoes the mood of these weeks,

With all its change of time and tide

Its living things, its earth and sky,

Are nothing to their mind and eye.

And heedless as the dead are they

Of aught around, above, beneath;

As if all else had pass’d away

They only for each other breathe …

Of guilt, of peril, do they deem

In that tumultuous dream?74

There is something, in fact, of the magic of Pasternak’s Dr Zhivago about Byron’s and Augusta’s illicit exile at Newstead, isolated from criticism and responsibilities by the impenetrable winter landscape, as safe among the ruins of the abbey as Yuri and Lara in the frozen wastes of Varykino. At the edge of Newstead’s cloistered world lurked the wolves, but like Zhivago watching their shadows in the half-light of dusk, Byron could pretend for the moment that they were merely dogs. To be alive, and to live in the present, was enough. All his restless search after sensation was sunk in ‘sluggish’ content. Even the desire or need to write – for Byron the ‘lava of the imagination’75 – was gone. Happy, he had neither need nor urge to create. He felt, he told Murray in a revealing metaphor for his poetic life, as he did when recovering from fever in Patras – ‘weak but in health and only afraid of a relapse.’ ‘I shall keep this resolution’, he wrote of his determination to give up scribbling, ‘for since I left London – though shut up – snowbound – thawbound – & tempted with all kinds of paper – the dirtiest of ink – and the bluntest of pens – I have not even been haunted by a wish to put them to their combined uses.’76

The wolves, though, were not dogs, and with the Tory press in full voice following the publication of his poetic squib against the Prince of Wales, Caroline Lamb still primed for trouble and his friends increasingly nervous, Byron was never going to be allowed to forget it. Characteristically, just as the previous year Caroline’s antics had frightened him back from the abyss, his moods now swung between defiance and compromise, between talk of the exile he had been threatening for almost a year and a marriage – any marriage – that might yet be his ‘salvation’ from the feelings that he confessed to Lady Melbourne ‘are a mixture of good and diabolical’77.

After his first impetuous talk of exile, Augusta too was beginning to look on the idea as the only way of averting catastrophe. There is little doubt that she would have gone abroad with him the previous summer if he had pressed her, but in the nature of things she had more to lose than he did and for a mother as indulgently devoted as Augusta, the thought of abandoning any of her children – Georgiana, her eldest, had been born in the first week of November 1808, Augusta Charlotte, a little over two years later and a son, George, in June the next year – could never have been a bearable option.

George was still only a baby when Byron first proposed exile to Augusta, however, and it was probably her two daughters who most exercised her concern. From an early age Augusta Charlotte had begun to exhibit the symptoms of autism that would eventually lead her to an asylum in Kensal Green, and yet in her different way the oldest, ‘Georgey’ – traditionally Byron’s favourite – was as much of a worry as her sister, constantly ill and as cripplingly and elusively shy as Augusta herself had been as a child.

And even with Augusta’s easy belief in the workings of a benevolent providence – virtually the only legacy from her pious Holderness grandmother – she must have felt that she had used up not just her small stock of courage but her luck when the birth of a third daughter in April passed without any gossip. It is impossible to tell from the few elliptical comments in Byron’s letters how anxious they had been in advance, but whatever his thoughts on the child he was certainly concerned enough for Augusta to journey up from London to the Leighs’ home outside Newmarket in the days before her confinement.

For all the space and time that has been expended on the subject, the only thing that can be said with any certainty of the paternity of Elizabeth Medora Leigh, is that it cannot be known. It would seem likely that Byron and Augusta both initially believed that she was his child, and yet there is not a single scrap of evidence – not a remark or silence – that cannot be equally well interpreted to support either side of the argument. ‘Oh! but it is worth while’, Byron reported to Lady Melbourne – in the one notorious, throw-off paragraph on which a whole speculative industry has been raised,

I can’t tell you why – and it is not an ‘Ape’ [an apparent reference to medieval incest superstitions] and if it is – that must be my fault – however I will positively reform – you must however allow – that it is utterly impossible I can ever be half as well liked elsewhere – and I have been all my life trying to make someone love me – & never got the sort I preferred before. But positively she and I will grow good – and all that – & so we are now and shall be these three weeks & more too.78

For all Byron’s resolutions, however, the choice of the name Medora – the heroine of his Corsair – smacks of the kind of brinkmanship that threatened disaster at any moment. It has been argued, with some plausibility, that she was in fact called after the Oaks winning filly of 1813, but even if that is true Augusta – for all her ‘goosiness’ – was astute enough to know that in anything to do with Byron it was the perception rather than the reality of things that mattered.

She had, in fact, her own idea for Byron’s wife, Lady Charlotte Leveson-Gower, but since the previous autumn an alarmed Lady Melbourne had been keeping a far more serious candidate waiting in the wings. For a time during his Eywood idyll there had been a slight froideur between her and Byron, but one of the great secrets of Lady Melbourne’s influence was a talent for absorbing slights and from the first threatening appearance of Augusta in Byron’s life she had been as ready to sacrifice her niece for his safety as she had been a year earlier for her own dynastic needs.

There are moments in the relationship of Byron and Annabella Milbanke that tilt the sympathies violently in one direction or another and the intervention of Lady Melbourne is one of these. There is no need to sentimentalise the broadly ‘Austenish’attitudes to marriage of Annabella herself, but the machinations of her aunt over the next fifteen months belong to another league altogether, raising the cynicism of the Regency marriage market to levels for which Glenarvon or Les Liaisons Dangereuses – the constant point of reference among her family for Lady Melbourne – provide no real preparation.

Lady Melbourne’s letters to Byron were always cooler, more discreetly circumspect, than his to her, and so it is difficult to be sure of her motives in this matter. It is clear that she was both genuinely fond of Byron and alarmed for him, but for a woman who only had to see a happy marriage, it was said, to want to destroy it, the appeal of the match must have been as much aesthetic as practical – the pure unalloyed pleasure of uniting two people so symmetrically ill-suited as Annabella and Byron, ‘the spoilt child of seclusion, restraint and parental idolatry’ and ‘the spoilt child of genius, passion, and the world,’79 as Mrs Stowe later described them.

Lady Melbourne’s performance was one of dazzling cynicism as she brought them together again, interpreting one to the other, revealing or concealing as needed, playing equally on the weaknesses of Byron and Annabella until each imagined the initiative their own. There was a streak of passivity in Byron’s nature that had always made him putty in Lady Melbourne’s hands, but with her romantic high-mindedness and naivety her niece proved no less easy to manage.

After almost a year in which she had time to reflect on the loneliness of moral superiority and the dullness of domestic life without the frisson of Byron’s attentions, Annabella was ripe for persuasion. ‘I have received from Lady Melbourne an assurance of the satisfaction you feel in being remembered with interest by me,’ her first direct letter to him had begun on cue on 22 August 1813 – midway between the beginning of his affair with Augusta and his half-hearted pursuit of Lady Frances Webster,

Let me fully explain this interest, with the hope that the consciousness of possessing a friend whom neither Time nor Absence can estrange may impart some soothing feeling to your retrospective views.80

One of the supreme temptations of the novel, E.M. Forster once confessed, is the desire to give characters the happiness that ‘real life’ denies them, and this first letter of Annabella’s can stir the same kind of emotions. She was so much in the habit of regarding herself in fictional terms that it would be hard not to follow suit anyway, but the cruelty of her fate now was to find herself less the heroine of her own shaping than the dupe of a Leclos plot over which she had no control. ‘You have remarked the serenity of my countenance,’ she went on,

but mine is not the serenity of one who is a stranger to care, nor are the prospects of my future untroubled. It is my nature to feel long, deeply, and secretly, and the strongest affections of my heart are without hope. I disclose to you what I conceal even from those who have most claim to my confidence, because it will be the surest basis of that unreserved friendship which I wish to establish between us … Early in our acquaintance, when I was far from supposing myself preferred by you, I studied your character. I felt for you, and I often felt with you. You were, as I conceived, in a desolate position, surrounded by admirers who could not value you, and by friends to whom you were not dear. You were either flattered or persecuted. How often have I wished that the State of Society would have allowed me to offer you my sentiments without restraint.81

With its oblique and frustrated demand to be heard this might anticipate the great climax of Persuasion, but Annabella was no more an Anne Elliot than Byron was Captain Wentworth. From her earliest youth she had dramatised herself as the self-sacrificing heroine of her historical daydreams, and the girl who had stood by Howard in her fantasies now abandoned herself to the role of Byron’s redeemer, uniting herself with him in an imaginary communion of souls that transcended time, place or vulgar self-interest. ‘Surely the Heaven-born genius without Heavenly grace must make a Christian clasp the blessing with greater reverence & love, mingled with a sorrow as a Christian that it is not shared’, she wrote to her old confidante Lady Gosford in her most ecstatic vein,

Should it ever happen that he & I ever offer up a heartfelt worship together – I mean in a sacred spot – my worship will then be most worthy of the spirit to whom it ascends. It will glow with all the devout and grateful joy which mortal breast can contain. It is a thought too dear to be indulged – not dear for his sake, but for the sake of man, my brother man, whomever he be – & for any poor, unknown tenant of this earth I believe I should feel the same. It is not the poet – it is the immortal soul lost or saved.82

In one of her ‘Auto-descriptions,’ Annabella confessed this inability to distinguish fiction from fact, but what had been harmless enough in the child was profoundly dangerous in the adult. In the early days of their acquaintance she had self-consciously distanced herself from the ‘Byromania’ of London, but as she realised with something like panic how much she had lost in turning him down, she set about desperately trying to recreate Byron in an image she could square with her conscience, blindly moving with every exchange of letters towards marriage with a man she scarcely knew. ‘I entreat you then to observe the more consistent principles of unwearied benevolence’, she wrote to Byron in the language of a tabloid astrologer,

No longer suffer yourself to be the slave of the moment, nor trust your noble impulses to the chances of Life. Have an object that will permanently occupy your feelings & exercise your reason. Do good. Your powers peculiarly qualify you for performing those duties with success, and may you experience the sacred pleasure of having them dwell in your heart!83

It is clear from Byron’s reply that Annabella’s tone had startled him, but if he had to sacrifice Augusta, it hardly seemed to matter whom he married. ‘To the part of your letter regarding myself’, he wrote back, having first assured her that she was the only person with whom he had ever contemplated marriage,