Читать книгу Lord Byron’s Jackal: A Life of Trelawny - David Crane - Страница 7

2 THE SUN AND THE GLOW-WORM

Оглавление‘You won’t like him.’

Byron to Teresa Guiccioli 1

IT MUST HAVE BEEN sometime in the autumn of 1819 or the beginning of 1820 that Trelawny finally left England for the Continent, travelling first to Paris where his mother was chaperoning his sisters on a predatory hunt for husbands, and from there to Geneva.

With the poverty of letters from this time it is impossible to be dogmatic about Trelawny’s motives but there would have been compelling reasons other than disappointment and money for his decision to live abroad. There appears to have been nothing particular in his choice of Switzerland, but for a man of his burgeoning radicalism the England of Castlereagh and the Peterloo Massacre can have seemed no place to be, a country frozen in the mini ice-age of reaction which gripped post-Napoleonic Europe, a land, in Shelley’s savage assault, of,

An old, mad, blind, despised, and dying king, –

Princes, the dregs of their dull race, who flow

Through public scorn, – mud from a muddy spring, –

Rulers who neither see, nor feel, nor know,

But leech-like to their feinting country cling,

Till they drop, blind in blood, without a blow, –2

At a time when so many European liberals were seeking refuge in England, there seems something stubbornly wrongheaded in the reverse process, but for Trelawny at least the freedom the Continent offered had more to do with the texture of life than any considered set of principles. Like so many men of his nation and class nineteenth-century Europe represented above all else a continuation of the eighteenth century ‘by other means’, an opportunity – heterosexual, homosexual, financial, social or whatever – to pursue a style of life which inflation and the looming threat of ‘Victorian’ morality was endangering at home.

It was an opportunity he embraced with relief and gusto, but amidst the shooting, hunting and fishing that signalled a reabsorption into his own class, a meeting occurred that was to change the direction of his life for good. A family friend of the Trelawnys from the West Country, Sir John Aubyn, kept a generous if irregular open house at his villa just outside Geneva, and it was in this motley expatriate world that Trelawny first met Edward Williams, an Indian army officer living in Switzerland as a married man with the wife of a fellow officer, and Thomas Medwin, the cousin of Percy Bysshe Shelley.

The friendship of Williams, at least, was one that Trelawny treasured all his life, but more important, it was through these two men that he now found himself drawn into the Italian orbit of Byron and Shelley. There is no way of being sure when he first came across the name or work of a poet who, in 1820, was known mainly for his atheism, but Trelawny’s account invests the occasion with a significance that is poetically if not literally true. The scene is set in Lausanne in 1820, during a conversation with a bookseller-friend, who would translate passages of Schiller, Kant or Goethe for an ex-midshipman still painfully conscious of his lack of education. The story forms the opening scene of his Records of Shelley, Byron, and the Author and among the apocrypha of his early life it holds a special place.

One morning I saw my friend sitting under the acacias on the terrace in front of the house in which Gibbon had lived, and where he wrote the Decline and Fall. He said, ‘I am trying to sharpen my wits in this pungent air which gave such a keen edge to the great historian, so that I may fathom this book. Your modern poets, Byron, Scott, and Moore, I can read and understand as I walk along, but I have got hold of a book by one that makes me stop to take breath and think.’ It was Shelley’s ‘Queen Mab’. As I had never heard that name or title, I asked how he got the volume. ‘With a lot of new books in English, which I took in exchange for old French ones. Not knowing the names of the authors, I might not have looked into them, had not a pampered, prying priest smelt this one in my lumber-room, and after a brief glance at the notes, exploded in wrath, shouting out, ‘Infidel, jacobin, leveller: nothing can stop this spread of blasphemy but the stake and the faggot; the world is retrograding into accursed heathenism and universal anarchy!’ When the priest had departed, I took up the small book he had thrown down, saying, ‘Surely there must be something here worth tasting.’ You know the proverb, ‘No person throws a stone at a tree that does not bear fruit.’

‘Priests do not’, I answered; ‘so I, too, must have a bite of the forbidden fruit.’3*

Set alongside the impact of Byron on Trelawny, the influence of Shelley’s poetry seems virtually negligible, but this, in stylized form, is still one of the key moments of his life. A few days after this exchange he was breakfasting at a hotel in Lausanne, when a chance conversation with an Englishman on a walking holiday with two women gave him his first opportunity to test this new enthusiasm. It was only after their party had broken up that Trelawny learned that the ‘self-confident and dogmatic’ stranger was Wordsworth, but chasing him down again he ‘asked him abruptly what he thought of Shelley as a poet.

‘Nothing,’ he replied, as abruptly.

‘Seeing my surprise, he added, ‘A poet who has not produced a good poem before he is twenty five, we may conclude cannot, and never will do so.’

‘The Cenci!’ I said eagerly.

‘Won’t do,’ he replied, shaking his head, as he got into the carriage: a rough-coated Scotch terrier followed him.

‘This hairy fellow is our flea-trap,’ he shouted out as they started off …

I did not then know that the full-fledged author never reads the writings of his contemporaries, except to cut them up in a review – that being a work of love. In after years, Shelley being dead, Wordsworth confessed this fact; he was then induced to read some of Shelley’s poems, and admitted that Shelley was the greatest master of harmonious verse in our modern literature.4

It says a lot for Trelawny’s critical judgement that, almost alone and untaught, he could have discovered Shelley for himself, but there must also have been more personal and less literary factors that helped quicken his new interest. For a man who saw himself in the self-dramatizing terms he so habitually used, the exiled poet would have offered a mirror to his own miserable experience, and if Shelley was merely the ‘glow-worm’ to Byron’s ‘sun’, then that can only have made him appear more accessible. The arrival of Medwin meant too that the chance of meeting him was something that had probably been discussed from the earliest days in Switzerland, but the unlamented death of Trelawny’s father in 1820 put any thoughts of Italy back by at least a year. Travelling in his own carriage through Chalon-sur-Saône, where he left Edward and Jane Williams to winter in genteel poverty, he continued on to England with his financial hopes high only to discover that he was no better off than he had been before. The old uncertainty of the allowance, the galling necessity of tempering hatred with self-interest, was gone, but there was to be no more money. He had been left £10,000 in 3% gilt-edged stocks which gave him an income of £300 a year.

The evidence for Trelawny’s movements during these months is as sketchy as for any time of his life, but it is likely that arriving in England at the end of 1820 he found himself in no hurry to leave, staying at his mother’s new London home in Berners Street before returning to the Continent in the May or June of 1821.

It is at this moment as one begins to attempt to chart his steps, however, that it becomes obvious just how futile an exercise it is, and just how far at this point a traditional sense of ‘biographical’ time must give way to what could be called ‘Trelawny’ time. Because to any observer totting up the weeks and months spent shooting and hunting during these years a picture emerges of a life hopelessly and terminally adrift, and yet for Trelawny himself this same time seems to have been crushed into a series of defining highlights that obliterate all else, secular epiphanies which, in the great drama he made of his life, assert a pattern of significance – of destiny – that biography can do nothing but follow.

Throughout his life there would be an almost Marvellian fierceness in the way Trelawny would seize his opportunities and in 1820 this destiny seemed to him to lead nowhere but Italy. Through the summer of 1821 he hunted and fished with an old naval friend Daniel Roberts in the Swiss mountains, but beneath the seemingly aimless wanderings the real business of his life was already taking shape. In April 1821, Edward Williams had written to him from Pisa, where he and Jane were living after a bleak winter of ‘soupe maigre, bouilli, sour wine, and solitary confinement’ at Chalon-sur-Saône.5 He was, he told Trelawny, already an intimate of Shelley. They were planning a summer’s boating together, ‘adventuring’ among the rivers and canals of that part of Italy. ‘Shelley’, he wrote, tantalizingly

is certainly a man of most astonishing genius in appearance, extraordinarily young, of manners mild and amiable, but withal frill of life and fun. His wonderful command of language, and the ease with which he speaks on what are generally considered abstruse subjects, are striking; in short, his ordinary conversation is akin to poetry, for he sees things in the most singular and pleasing lights; if he wrote as he talked, he would be popular enough. Lord Byron and others think him by far the most imaginative poet of the day. The style of his lordship’s letters to him is quite that of a pupil, such as asking his opinion, and demanding his advice on certain points, &. I must tell you, that the idea of the tragedy of ‘Manfred’, and many of the philosophical, or rather metaphysical, notions interwoven in the composition of the fourth Canto of ‘Childe Harold’, are of his suggestion; but this, of course, is between ourselves.6

Trelawny printed this letter in his history of this period of his life, the Records of Shelley, Byron and the Author. Back to back with it, as if the intervening eight months had simply not existed, comes a second letter from Williams, written in the following December and giving the momentous news of Byron’s arrival.

My Dear Trelawny,

Why, how is this? I will swear that yesterday was Christmas Day, for I celebrated it at a splendid feast given by Lord Byron to what I call his Pistol Club – i.e. to Shelley, Medwin, a Mr Taaffe, and myself, and was scarcely awake from the vision of it when your letter was put into my hands, dated 1st of January, 1822. Time flies fast enough, but you, in the rapidity of your motions, contrive to outwing the old fellow … Lord Byron is the very spirit of the place – that is, to those few to whom, like Mohannah, he has lifted his veil. When you asked me in your last letter if it was probable to become at all intimate with him, I replied in a manner which I considered it most prudent to do, from motives which are best explained when I see you. Now, however, I know him a great deal better, and I think I may safely say that point will rest entirely with yourself. The eccentricities of an assumed character, which a total retirement from the world almost rendered a natural one, are daily wearing off. He sees none of the numerous English who are here, excepting those I have named. And of this I am selfishly glad, for one sees nothing of a man in mixed societies. It is difficult to move him, he says, when he is once fixed, but he seems bent upon joining our party at Spezzia next summer.

I shall reserve all that I have to say about the boat until we meet at the select committee, which is intended to be held on that subject when you arrive here. Have a boat we must, and if we can get Roberts to build her, so much the better … 7

With the entry of Byron into Shelley’s world Trelawny’s twin deities were in place. Even before Williams’s second letter, however, he was already making ready for Italy. He had shipped his guns and dogs to Leghorn in preparation for a winter’s hunting in the Maremma, but with this news of bigger game on the banks of the Arno, the woodcock were now going to have to wait their turn.

Travelling south from Geneva with his friend Roberts, shooting, fishing and sketching as they went, Trelawny finally reached Pisa in the January of 1822 to take up his place among the circle that had formed around Shelley. Since the early spring of 1818 when they left England for the last time, Shelley and his tribe of dependents had been wandering across the Continent, moving restlessly from one Italian town to another, from Milan to Bagni di Lucca, Venice, Naples, Rome, Leghorn, Florence, and then, in the January of 1820, to Pisa, his penultimate resting place in that ‘Paradise of exiles – the retreat of Pariahs’ as he called nineteenth-century Italy.8

At the beginning of 1822, when Trelawny first joined them, Shelley and his wife Mary were living above Edward and Jane Williams in the Tre Palazzi di Chiesa at the eastern end of the Lung’ Arno, diagonally across the river from the Palazzo Lanfranchi which Byron had taken the previous November. Anxious to be with them as quickly as he could, Trelawny had left Roberts at Genoa and hurried on alone. He arrived late, and after putting up his horse at an inn and dining, hastened to the Tre Palazzi to renew acquaintances with the Williamses and to meet Shelley. He was greeted by his old friends in ‘their earnest cordial manner’, and the three were deep in conversation,

when I was rather put out by observing in the passage near the open door, opposite to where I sat, a pair of glittering eyes steadily fixed on mine; it was too dark to make out whom they belonged to. With the acuteness of a woman, Mrs Williams’s eyes followed the direction of mine, and going to the doorway, she laughingly said.

‘Come in, Shelley, it’s only our friend Tre just arrived.’

Swiftly gliding in, blushing like a girl, a tall thin stripling held out both his hands; and although I could hardly believe as I looked at his flushed, feminine, and artless face that it could be the Poet, I returned his warm pressure. After the ordinary greetings he sat down and listened. I was silent from astonishment: was it possible this mild-looking beardless boy could be the veritable monster at war with all the world? – excommunicated by the Fathers of the Church, deprived of his civil rights by the fiat of a grim Lord Chancellor, discarded by every member of his family, and denounced by the rival sages of our literature as the founder of a Satanic school? I could not believe it; it must be a hoax.9

This account was published in his Records almost sixty years after, at a time when Trelawny was established beyond challenge as the last and greatest of Byron’s and Shelley’s friends, and yet even if much of its ease is of a later date, he clearly slid into the world that revolved around the two poets as if he had known no other. Within twenty-four hours of this first sight of Shelley he was playing billiards with Byron at the Palazzo Lanfranchi, coolly holding his own in conversation (and there is no more conversationally demanding a game than billiards), the acolyte an immediate familiar, a welcome addition to the daily shooting parties and drama plans and as interesting an object to his new friends as they were to him.

Indeed, when Trelawny first burst upon Byron’s Pisan world that January, launching himself from nowhere with the same fanfare of lies that fill his Adventures, it seemed to them that here at last was the Byronic hero made flesh. Here was a Conrad with a Gulnare in every port, a Lara who had exhausted all human emotion, who had murdered and pillaged, whored and sinned; had loved only to cremate his Zela’s corpse on the edge of a Javan bay; betrayed and been betrayed, deserted from the Royal Navy, fought beside his pirate-hero De Ruyter, and all, as Mary Shelley noted with that fine lack of irony that is her hallmark, ‘between the age of thirteen and twenty.’10

Appropriately, in fact, it is to the author of Frankenstein that we owe the first sustained description of Trelawny that we have. The arrival of this exotic figure among their small circle was important enough to warrant a long entry in her journal, and a month later she was still sufficiently intrigued to write to an old friend, Mary Gisborne, of her giovane stravagante. He was, she said

a kind of half Arab Englishman – whose life has been as changeful as that of Anastasius & who recounts the adventures of his youth as eloquently and well as the imagined Greek – he is clever – for his moral qualities I am yet in the dark – he is a strange web which I am endeavouring to unravel – I would fain learn if generosity is united to impetuousness – Nobility of spirit to his assumption of singularity & independence – he is six feet high – raven black hair which curls thickly & shortly like a More – dark, grey – expressive eyes – overhanging brows, upturned lips & a smile which expresses good nature & kindheartedness – his shoulders are high like an Orientalist – his voice is monotonous yet emphatic & his language as he relates the events of his life energetic & simple – whether the tale be one of blood & horror or irresistable comedy. His company is delightful for he excites me to think and if any evil shade the intercourse that time will tell.11

It seems fitting in a sense that we have no painting or description of Trelawny before this time, that we have to wait until he was the ‘finished article’ strutting the public stage to know in any detail what he might have looked like. There are moments when one feels that some glimpse of a younger and more vulnerable Trelawny might help ‘explain’ him in some way, but there is no image which even half suggests the ghost of another self – either of the boy who cried himself to sleep that first night at school, or the man who sat through Sarah Prout’s testimony in the divorce courts. By 1822, cuckold and boy were both gone, hidden behind the mask that so intrigued Mary Shelley, that stares out still from portrait after portrait done over the next fifty years – the eyes aggressive, challenging, the nose aquiline, the lines already set into the obdurate mould Millais caught in old age: the face, as Mary Shelley suggests, of Thomas Hope’s Anastasius, the one romantic outcast that Byron wept that he had not himself created.

It has always been baffling that Trelawny could have got away with his tales and fantasies among the Pisan Circle, but at a more mundane level it is scarcely less astonishing to find the daughter of Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft still thinking and writing of an uneducated midshipman in these terms after almost a month of his company.

But if charm, singularity and good-looks were possibly enough to provoke her fascination with him, something more than a lazy and tolerant male camaraderie is needed to explain away the confidence with which he adjusted to the sophisticated literary and political interests of Byron and Shelley.

The admirers of the two poets have traditionally agreed on very little but if there is one thing that does unite them it is a comforting belief that Trelawny was only a marginal figure in their Pisan Circle. The principal reason for this is a natural and proper reaction to the inflated claims he made for himself in his later memoirs, and yet even when one has discounted his exaggerations it is still clear that there was a genuine warmth in their welcome that reflects as well on him as it does on them.

There was a kindness about Shelley and an aristocratic carelessness about Byron which must have smoothed any awkwardness, but in such a circle Trelawny would have had to earn his place with his conversation or simply disappear. In old age the force and vitality of his talk left an indelible impression on all who met him, and even at thirty he was obviously a brilliant and charismatic story-teller with the power to interest men whose lives in many ways had been more circumscribed than his own.

Trelawny’s strength and skills, his shooting, his boxing and sailing were all valued currencies in Byron’s world and yet the explanation of his success that often goes forgotten is the simple fact that he was a man of real if unformed talent. In terms of sophistication and learning he might well have been out of his depth in this alien literary world, but if one takes out Byron and Shelley and that strange fluke of a novel, Frankenstein, was there anything produced by the Pisan Circle that could remotely compare with the books Trelawny would go on to write?

Williams, Medwin, Taafe, Mrs. Mason, Claire Clairmont, even Leigh Hunt? – the truth is that Trelawny wrote at least one book and probably two that were beyond the compass of any of them. There is certainly nothing in his letters from this period to suggest he had yet found the voice to match his abilities, but there must have been an inner conviction of power that rubbed off on others, a strong and even savage faith in his own singularity that enabled him to brazen out his adopted role in a world whose very lifeblood was the imagination. It is again as if all those years of misery that seem so arid and sterile from the outside had been nothing of the sort, but rather an essential apprenticeship in romantic alienation, a training in disaffection whilst the inner man, fed on little more than the poetry of Byron and Shelley, shaped for himself a destiny he was ready to seize the moment it was offered him.

Not even Trelawny, though, in the drawn-out loneliness of his life at sea or the humiliations of the divorce courts, could have anticipated that destiny would bring him to Italy in time to play his part in English Romanticism’s Götterdämmerung. Neither, during his first weeks, was there any hint of the dramas that lay ahead. Through the early months of 1822, the sexual and political tensions that were always part of their Pisan world were stirring ominously beneath the surface, and yet in the very ordinariness of Edward Williams’s journal for this same time one glimpses in its last, leisurely days a world that feels as if it might have gone on for ever.

At the end of March their peace was threatened by an unpleasant and absurdly inflated incident with a sergeant major called Masi, a degrading brawl that ended in Masi’s wounding and ultimately Byron’s exit from Pisa. Some of the details of this incident are still obscure but it began when the party of Byron and Shelley, returning from shooting practice, took umbrage at a dragoon who galloped through their ranks on the road into Pisa. When the English gave chase there was a scuffle beneath the city gate that left Shelley on the ground and a Captain Hay wounded, but it was only when an unknown member of Byron’s household subsequently stabbed Masi outside the Palazzo Lanfranchi that the incident threatened serious consequences.

After one fraught night through which he was not expected to live, Masi recovered from his wound. But anti-English feeling ran high in the city, and even before the Gambas, the family of Byron’s mistress Teresa Guiccioli, were expelled and Byron went with them, Shelley and Mary had determined to quit Pisa.

The final calamity, when it came, however, sprang from a different direction with all the suddenness and violence of the Mediterranean storm that caused it. From long before Trelawny’s appearance there had been excited talk in Shelley’s circle of boats and boating expeditions, and when Trelawny arrived in January 1822 he immediately assumed, as the ex-naval man among them, a leading role in their schemes. In his journal for 15 January, Williams noted that Trelawny had brought them a model for an American schooner, and that they had settled to have a 30-foot boat built along its lines. Within days an order was placed through Daniel Roberts for this boat, together with a larger vessel that Trelawny was to skipper himself for Byron. Then, on 5 February, Trelawny wrote to Roberts again with his last, fateful instructions, dangerously reducing the original specifications for Shelley’s boat by almost half.

Dear Roberts,

In haste to save the Post – I have only time to tell you, that you are to consider this letter as definitive, and to cancel every other regarding the Boats.

First, then, continue the one that you are at work upon for Lord B. She is to have Iron Keel, copper fastenings and bottom – the Cabin to be as high and roomy as possible, no expense to be spared to make her a complete BEAUTY! We should like to have four guns, one … as large as you think safe – to make a devil of a noise!– fitted with locks – the swivels of brass! – I suppose from one to three pounders.

Now as to our Boat, we have from considerations abandoned the one we wrote about. But in her lieu – will you lay us down a small beautiful one of about 17 or 18 feet? To be a thorough Varment at pulling and sailing! Single handed oars, say four or six; and we think, if you differ not, three luggs and a jib – backing ones!12

It is given to few men to kill two major poets, but the friend to whom Byron turned for his doctors and Shelley for his boat has claims to be considered one of the seminal influences on nineteenth-century literature. It was not until the middle of May that the Don Juan as she was named was finally delivered to Shelley at Lerici, but even then there were further sacrifices of stability to elegance to be made, additions of a false stern and prow to accentuate her lines, and a new set of riggings which gave her, to Williams’s eye, all the glamour and prestige of a 50-ton vessel.

Fast, graceful and spirited as she was, the Don Juan was certainly no craft to survive the approaching storm into which, with Shelley, Edward Williams and the boat-boy Charles Vivian on board, she disappeared off Leghorn on 8 July 1822. Trelawny had initially intended to accompany them on their journey back to Lerici in Byron’s Bolivar, but at the last was delayed by the port authorities. Sullenly and reluctantly, he refurled the Bolivar’s sails, and watched the Don Juan’s progress through his spy-glass. The sea had the smoothness and colour of lead, but to the south-west black storm-clouds were massing dangerously. The devil, he was told by his Genoese mate, was brewing mischief. On shore, an anxious Daniel Roberts took a telescope to the top of the lighthouse, straining to get one last view of the boat before it vanished into the thickening mist.

Sometime after six the storm broke with a sudden and spectacular violence. The captain of an Italian vessel which had made it back to the safety of the harbour reported sighting the Don Juan in mountainous seas. He had offered to take its crew aboard, but a voice had cried back ‘No’. A sailor called across for them to reef their sails at least, but when Williams was seen trying to lower them Shelley had seized an arm, angrily determined to stop him.13*

It was the last time the Don Juan was seen. Over the next ten days, while Mary and Jane waited in agony and Trelawny tirelessly patrolled the coast, pieces of wreckage followed by the bodies of Vivian, Williams and Shelley were washed ashore. Shelley’s corpse was found on the beach at Viareggio. After so long in the water the face was gone but Trelawny was able to identify him by the clothes and a copy of Keats’s poems still folded back in his jacket pocket. The body was buried where it lay in a shallow grave of quicklime, and Trelawny hurried to the Casa Magni on the Gulf of Spezia, the summer house where the Shelleys and Williamses had been living since the end of April. Over fifty years later he returned to the memory in a passage honed by time and repetition.

I had ridden fast, to prevent any ruder messenger from bursting in on them. As I stood on the threshold of the house, the bearer, or rather confirmer, of news which would rack every fibre of their quivering frames to the utmost, I paused, and looking at the sea, my memory reverted to our joyous parting only a few days before.

The two families, then, had all been on the veranda, overhanging a sea so clear and calm that every star was reflected on the water, as if it had been a mirror; the young mothers singing some merry tune, with the accompaniment of a guitar. Shelley’s shrill laugh – I heard it still – rang in my ears, with Williams’ friendly hale, the general buona notte of all the joyous party, and the earnest entreaty to me to return as soon as possible, and not forget the commissions they had given me.

My reverie was broken by a shriek from the nurse Caterina, as, crossing the hall she saw me in the doorway. After asking her a few questions, I went up the stairs, and, unannounced, entered the room. I neither spoke, nor did they question me. Mrs Shelley’s large grey eyes were fixed on my face. I turned away. Unable to bear this horrid silence, with a convulsive effort she exclaimed –

‘Is there no hope?’

I did not answer, but left the room, and sent the servant with the children to them. The next day I prevailed on them to return to Pisa. The misery of that night and the journey the next day, and of many days and nights that followed, I can neither describe nor forget.14

There were quarantine laws to meet before the bodies of Shelley or Williams could be touched, but the man who claimed to have cremated his eastern bride was more than up to the challenge of a proper funeral. Mary Shelley had at first wanted her husband buried alongside their son in the Protestant cemetery in Rome, but in the end more exotic council prevailed. On 14 August, the body of Williams was finally exhumed and cremated in a macabre dress rehearsal for what was to follow. The next morning, with Byron and the newly arrived Leigh Hunt present, it was Shelley’s turn in a scene which in all its gruesome detail has etched itself onto the Romantic imagination.

The lonely and grand scenery that surrounded us so exactly harmonized with Shelley’s genius, that I could imagine his spirit soaring over us. The sea, with the islands of Gorgona, Capraja, and Elba, was before us; old battlemented watch-towers stretched along the coast, backed by the marble-crested Appenines glistening in the sun, picturesque from their diversified outlines, and not a human dwelling was in sight. As I thought of the delight Shelley felt in such scenes of loneliness and grandeur whilst living, I thought we were no better than a herd of wolves or a pack of wild dogs, in tearing out his battered and naked body from the pure yellow sand that lay so lightly over it, to drag him back to the light of day; but the dead have no voice, nor had I power to check the sacrilege – the work went on silently in the deep and unresisting sand, not a word was spoken, for the Italians have a touch of sentiment, and their feelings are easily excited into sympathy. Byron was silent and thoughtful. We were startled and drawn together by a dull hollow sound that followed the blow of a mattock; the iron had struck a skull, and the body was soon uncovered. Lime had been strewn on it; this or decomposition had the effect of staining it of a dark and ghastly indigo colour. Byron asked me to preserve the skull for him; but remembering that he had formerly used one as a drinking-cup, I was determined Shelley should not be so profaned. The limbs did not separate from the trunk, as in the case of Williams’s body, so that the corpse was removed entire into the furnace … After the fire was well kindled we repeated the ceremony of the previous day; and more wine was poured over Shelley’s dead body than he had consumed during his life. This with the oil and salt made the yellow flames glisten and quiver. The heat from the sun and fire was so intense that the atmosphere was tremulous and wavy. The corpse fell open and the heart was laid bare. The frontal bone of the skull, where it had been struck with the mattock, fell off; and, as the back of the head rested on the red-hot bottom bars of the furnace, the brains literally seethed, bubbled, and boiled as in a cauldron, for a very long time.

Byron could not face this scene, he withdrew to the beach and swam off to the ‘Bolivar’. Leigh Hunt remained in the carriage. The fire was so fierce as to produce a white heat on the iron, and to reduce its contents to grey ashes. The only portions that were not consumed were some fragments of bones, the jaw, and the skull; but what surprised us all was that the heart remained entire. In snatching this relic from the fiery furnace, my hand was severely burnt; and had anyone seen me do the act I should have been put into quarantine.15

In the long years ahead, Shelley’s funeral would come to seem the making of Trelawny, the beginning of his public ministry as high priest and interpreter of English Romanticism. During the short time that he had known Shelley and Byron he had certainly become an integral part of their Pisan world, but the truth is that it was his role at their deaths and not the friendship of a few brief months which gave him his apostolic authority over a generation infatuated with their memory.

In account after account over the next sixty years he would return to this summer of 1822 with ever new details, peddling scraps of history or bone with equal relish. Yet if his long-term strategy became one of ruthless self-promotion, in the short term Shelley’s death brought out a streak of selfless and generous kindness his earlier life had stifled. In the bleak and wearing months after the Don Juan went down, Trelawny almost single-handedly sustained the grieving widows, giving them not just unstinted emotional support but practical and financial help that earned their deep and genuine gratitude. ‘His whole conduct during his last stay here has impressed us all with an affectionate regard, and a perfect faith in the unalienable goodness of his heart,’16 Mary Shelley wrote to Jane Williams from Florence on 23 July 1823, shortly before her own departure for England where Jane had already gone. ‘It went to my heart to borrow the sum from him necessary to make up my journey,’ she wrote again only a week later, ‘but he behaved with so much quick generosity, that one was almost glad to put him to the proof, and witness the excellence of his heart.’17

Through the desolate winter of 1822–3 Trelawny came closer to Mary than at any time in their long relationship, but it was with another of Shelley’s circle that he formed during this time what is possibly the most enduring, if impenetrable, friendship of his life.

A curious compound of apparent opposites, of selfishness and generosity, common sense and fatuous silliness, of shrewd judgement and uncontrollable passion, of clinging dependence and brave and dogged self-sufficiency, Claire Clairmont is at once the most touching and exasperating member of Shelley’s and Byron’s world. She had been born in the spring of 1798 as the illegitimate child of a woman who went under the name of ‘Mrs Clairmont’, and at the age of three was taken with her brother Charles to Somers Town in London, where in the same year their mother met and married the widower of Mary Wollstonecraft, the great radical and political philosopher, William Godwin.

From the earliest age, Claire thus found herself in one of the most free-thinking and politically conscious households in England, the step-daughter of a famous writer and step-sister to another in the future Mary Shelley. As a child, too, she was raised and educated with the same care that was expended on the boys of the family, and she grew up with all the principles and beliefs that lay at the core of the Godwin ménage, as exuberantly and unapologetically a child of the revolutionary age as if she had indeed been Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft’s natural daughter.

When Claire was fourteen her half-sister, Mary, fell in love with the young poet and disciple of Godwin, Percy Bysshe Shelley. Shelley was already a married man when he first met Mary, but two years later the couple eloped to France and took Claire with them, walking, riding and slumming their way across the French countryside until poverty and Mary’s pregnancy brought them back to England and reality.

It is hard to imagine what the sixteen-year-old girl thought she was doing with Mary and Shelley in France at this time, but if her teasing and subversive presence in their lives is still one of the unresolved mysteries of biography, there was odder yet to come. Within two years of their triangular elopement and still only seventeen, she eclipsed Mary’s conquest of Shelley with a married poet of her own, throwing herself at Lord Byron with a reckless and infatuated passion that his indolent and self-indulgent nature was unable to resist. ‘An utter stranger takes the liberty of addressing you,’ she wrote to him above the assumed name of E. Trefusis.

It may seem a strange assertion, but it is none the less true that I place my happiness in your hands … If a woman, whose reputation as yet remained unstained, if without either guardian or husband to control, she should throw herself on your mercy, if with a beating heart she should confess the love she has borne you many years … could you betray her, or would you be silent as the grave?18

If a whole life can ever be said to hinge on a single action or judgement, then Claire Clairmont’s unprovoked assault on Byron in the March of 1816 is it. In the wake of the scandalous collapse of his marriage Byron was certainly ready for a brief and loveless affair, but to Claire it was the most important moment of her life, a moment at once of complete fulfilment and self-destructive folly which she was to regret for sixty bitter years.

Had the affair ended there and then, however, Claire Clairmont’s history might well have been very different, but in that same summer of 1816, a mixture of her persistence and Byron’s weakness saw it revived on the shores of Lake Leman and in January 1817 she gave birth to his daughter. The following March the baby was christened Clara Allegra Byron, but other than giving the child his name the father was unmoved. Boredom with Claire had long turned to an uncharacteristically implacable dislike of what he called her ‘Bedlam behaviour’, and even when the following year he agreed to assume responsibility for his daughter, it was an arrangement from which the mother was ruthlessly excluded.

It was this unstable, passionate and generous woman, with a past and pedigree to match – the step-daughter of Godwin, the sister-in-law of Shelley and the ex-mistress of Byron – with whom Trelawny now fell violently in love. Claire was still only twenty-three when they first met at the house of the Williamses in February 1822, a gifted linguist and musician, dark haired, clever and attractive enough – whatever the evidence of Amelia Curran’s Rome portrait – to have inspired at least one brilliantly shallow lyric of homage from Byron.

In her journal Claire recorded this first meeting without comment, and yet even had she felt any reciprocal interest at this time, the sudden death from typhoid of her daughter Allegra in the convent where Byron had placed her was soon to eclipse all else. In the immediate aftermath of the news Claire seems to have behaved with a dignity and calm that surprised everyone, but the silence of her journal over the next five months is an eloquent measure of a grief which only grew with the years.

It was a grief, too, which no one around could ignore, an event about which no one could remain neutral, and Allegra’s death marks the first major split in the Pisan Circle that had gathered around Byron and Shelley, the first bitter issue over which those battle lines were drawn that were to hold their partisan shape way beyond the deaths of the main protagonists.

At a time of such drama and tension it is difficult to see Trelawny remaining indifferent, but there is no clue to the way his relationship with Claire developed until in a sense it was all over. In the wake of Allegra’s and Shelley’s deaths his kindness must have brought her closer in the same way it did Mary and Jane, and yet as Claire prepared over the summer of 1822 to leave Italy there is nothing in any surviving correspondence that could possibly suggest a crisis in their friendship, and still less the torrent of passionate letters from Trelawny that followed her into her long exile as a governess.

That crisis is cryptically marked in her journal. The last prosaic entry had been for 13 April, just six days before Allegra’s death. It resumes again on Friday 6 September 1822, with a simple note of the date and nothing else. Three years later, however, while Claire was living on the country estate of her employers at Islavsk, outside Moscow, another entry gives some hint of what that date had meant to her. ‘Tuesday August 25th. Septr. 6th.’ she recorded, using both calendars

Lovely weather. I think a great deal of past times to-day and above all of this day three years, but the sentiments of that time are most likely long ago, vanished into air. This is life. So five to nothing but toil and trouble – all its sweets are like the day whose anniversary this is – more transitory than a shade – yet it had been otherwise if Inwalert had been different and I might have been as happy as I am now wretched.19

In Trelawny’s letters over the autumn and winter of 1822–3, however, the crackling fallout of that day in September has left a less ambiguous trace. It is impossible to say with any certainty what happened when they met for the last time on the banks of the Arno, but the bond that it established and its devastating impact on Trelawny are beyond question. Over the next months he sent letter after letter to Claire in Vienna, violent and tender, demanding and conciliatory, histrionic and emotionally truthful by turn. ‘A gnarled tree may bear good fruit,’ he gnomically declared from the back of his horse in one undated letter soon after, ‘and a harsh nature may find good council …’

let us be firm and staunch friends we both want friends – you have lost in Shelley one worthy to be called so – I cannot fill his place – as who can – but you will not find me altogether unworthy the office. Linked thus together we may defy the fate that separates us for a time – with united hearts – what can separate us … In solitude silence or absence I think of your words – and can even make sacrifices to reason … 20

The last six lines of this letter have been scratched out by Claire, but enough of Trelawny’s correspondence remains uncensored to underline the Byronic tenor of his courtship. You ‘tortured me almost into convulsions,’ he told her in a letter written from Pisa when he realized she was irreparably lost to him, ‘have left me fetid, morbid, and broken hearted.’

Why have you thus plunged me into excruciating misery by deserting him that would – but bleed on in silence my heart – let not the cold and heatless mock thee with their triumphs.21

‘Your weak impress of Love was a figure Trenched in ice; which with an hour’s heat dissolved to water!’ he complained on 4 October,

you! you! torture me Claire, your cold, cruel heartless letter has driven me mad – it is ungenerous under the mask of love – to enact the part of a demon … you have had my heart, and gathered, and gathered my crudest, idlest most entangled surmises … I am hurt to the very soul. I am shamed and sick to death to be thus trampled on & despised, my heart is bruised … much as endurance has hardened me, I must give you the consolation of knowing – that you have inflicted on me an incurable wound which is festering & inflaming my blood.22

‘I have used no false colours,’ he again told her with more emotional than literal truth, ‘no hypocrisy – enacted no part.’

I have as dispassionately as I could – disclosed my feelings … I loved you the first day, – nay before I saw you, – you loathed and heaped on me contumely and neglect till we were about to separate – Clare I love you and do what you will – I shall remain deeply interested for you. I think you are right in withdrawing your fate from mine – my nature has been perverted by neglect and disappointment in those I loved – my disposition is unamiable. I am sullen, savage, suspicious & discontented – I can’t help it – you have sealed me so.23

Somewhere behind the grief, the mortification and the posturing at Claire’s abandonment, however, Trelawny probably knew, as he suggests here, that she was right to keep their two fives apart. There seems no need to question the intensity of his feelings for her, and yet it is difficult to resist the sense that it was her history as much as herself that attracted him, or that his love was something that could flourish more easily in absentia.

This was something Claire, despite her genuine and lasting fondness for him, also recognized. ‘I admire esteem and love him;’ she wrote to Mary Shelley eight years later, when experience had damped down those passions that had ruined her life,

some excellent qualities he possesses in a degree that is unsurpassed but then it is exactly in another direction from the centre of my impetus. He likes a turbid and troubled life; I a quiet one; he is full of fine feelings and has no principles; I am full of fine principles but never had a feeling (in my life). He receives (every) all his impressions through his heart; I through my head. Che vuol? Le moyen de se rencontrer when one is bound for the North Pole and the other for the South.24

It is characteristic of Trelawny that at the same time as he was berating Claire for her inconstancy, he was consoling himself with other affairs, but without her or the circle that had gathered round Shelley and Mary, his life threatened to lapse back into the brainless rhythms of former days. On 22 November, he wrote half-heartedly to her of his plans. Byron’s boat, the Bolivar, which he had skippered, was laid up, but he had thoughts of shooting with Roberts and then sailing among the islands in the spring in the salvaged Don Juan. It was, he told her ‘a weary and wretched existence without ties,’ his life little more than ‘dying piecemeal’.25

Almost in spite of himself, however, there was a buoyancy about Trelawny that would always assert itself, and in Shelley’s death, too, he still had unfinished business. In January 1823, Shelley’s ashes had been deposited in the Protestant Cemetery at Rome, but when Trelawny visited the place in the spring he found them in a public grave, ‘mingled in a heap with five or six common vagabonds’.26

His distress at this indignity was certainly genuine, and yet a letter of Keats’s friend, Joseph Severn – complaining of Trelawny’s cavalier attitude to a memorial design Severn had done for the tomb – underlines just how far down the road to recovery he had come:

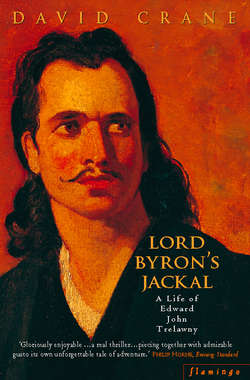

There is a mad chap come here – whose name is Trelawny. I do not know what to make of him, further than his queer, and, I was near saying, shabby behaviour to me. He comes on the friend of Shelley, great, glowing, and rich in romance. Of course I showed all my paint-pot politeness to him, to the very brim … I made the drawing, which cost us some trouble, yet after expressing the greatest liking for it, this pair of Mustachios has shirked off from it, without giving us the yea or no – without even the why or wherefore. – I was sorry at this most on Mr Gotts account, but I ought to have seen that this Lord Byron’s jackal was rather weak in all the points I could judge, though strong enough in stiletto’s. We have not had any open rupture, nor shall we, for I have no doubt that this ‘cockney corsair’ fancies he has greatly obliged us by all this trouble we have had. But tell me who is this odd fish? They talk of him here as a camelion who went mad on reading Ld. Byron’s ‘Corsair’.27

With the help of Severn, Trelawny had Shelley’s ashes disinterred and reburied in a ‘beautiful and lonely plot’28 near the pyramid of Caius Cestius. He added an inscription from The Tempest to Leigh Hunt’s simple ‘Cor Cordium’, and planted the grave with ‘six young cypresses and four laurels’.29 In a gesture which, in 1823, must have had more to do with a clinging sense of identification than inspired prescience, he then had his own grave dug next to that of Shelley – ‘so that when I die,’ as he reported back to Mary in a burst of necrophiliac chumminess,

there is only to lift up the coverlet and role me into its – you may he on the other side or I will share my narrow bed with you if you like.30

But if Shelley was gone Byron was still left, and for all the talk of death and world-weariness, the sniff of celebrity Trelawny had enjoyed in Pisa had been too intoxicating for him to face oblivion now with any equanimity. Throughout his life Trelawny would always ride the shifting thermals of their literary fame with effortless ease, but in truth it had always been the ‘sun’ rather than the ‘glow-worm’ that had warmed his youthful imagination into life, and it was to Byron now that he turned in search of a new role.

He was fortunate, too, in his timing, as events in both his and Byron’s lives now freed them from the chains of their Italian idleness. Trelawny was still writing long letters to Claire, but the first intensity of his attachment had cooled to something more honest, more in keeping with what they both wanted and needed of their friendship. In a letter written to her from Rome in April 1823, he told her that she had misunderstood his meaning, that he had never intended her staying with him. The following month he was more explict. ‘Now to proceed to your most urgent questions, which I have hitherto avoided,’ he wrote in reply to a lost letter:

As to my fortune – my income is reduced to about £500 a year – the woman I married having bankrupted me in fortune as well as happiness. If I outlive two or three relations – I shall, however, retrieve in some measure my fortunes – so you see, dear Clare how thoughtless and vain was my idea of our living together: as Keats says

‘Love in a hut, with water and a crust,

Is – Love, forgive us! cinders, ashes, dust;’

Poverty and difficulties have not – or ever will – teach me prudence or make me like Michael Cassio a great Arithmetician – all my calculations go to the devil – in anything that appeals to my heart – and this kind of prodigality has kept me in troubled water all my days: as to my habits – no Hermit’s simpler – my expenses are within even the limits of my beggarly means – but who can have gone through such varieties of life as I have – and not have formed a variety of ties with the poor and unfortunate; – I am so shackled with these that I do not think I have even a right to form a connection which would affect them – what abject slaves are us poor of fortune – enough of this hateful topic.

It is a source of great pleasure to me, your friendship – to be beloved – and Love – under whatever circumstances – is still happiness – the void in my affections is filled up – and though separate – I have lost that despairing dreary feeling of loneliness – I look forward with something of hope.

I am anxious to get to sea. Write to me here – and let me know your address – I do not like to importune you about writing. There are some pleasant women here, which induces me to go more into society than usual ….

Dear, I am not in the vein for writing –

Your unalterably

Attached

Edward.

May 15 1823

Florence31

At the time of this letter Trelawny probably had nothing fixed in mind when he spoke of the sea, but over the next months the unspoken possibility of joining Byron on an expedition took on a solid form. From the very start of their acquaintance there had always been desultory talk of travel in one direction or another, and when the idea of fighting for Greek independence suddenly became more than talk in the early summer of 1823, Trelawny was ready to join the crusade. ‘I wish Lord Byron was as sincere in his wish of going to Greece – as I am,’ he confided to Mary Shelley,

every one seems to think it a fit theatre for him … at all events tell him how willingly I will embark in the cause – and stake my all on the cast of the die – Liberty or nothing.32

By the early summer of 1823 Greece had been at war with Ottoman Turkey for just over two years, drawing men from all over Europe and America to a country that had long held a special place in the Western imagination. From the day in March 1751 when James Stuart and Nicholas Revett landed at the port of Athens to make the first accurate drawings of its ruins, travellers, painters, scholars, dilettanti, soldiers and architects had all made their way out to Greece, sketching and plundering its sites, charting its battlefields and searching the modern Greek’s physiognomy for some trace of its ancient lineaments, some link between the Greece which languished under Turkish rule and the land that had produced the poetry of Homer and the sculpture of the Acropolis.

It was in 1809 that the twenty-one-year-old Byron had first followed in this tradition, travelling with his long-suffering Cambridge friend John Cam Hobhouse through Ali Pasha’s Albania to Delphi, Athens, and on to Smyrna, Ephesus and Constantinople. In the years before this ‘pilgrimage’, Byron had gained a minor reputation in England as an aristocratic poetaster and satirist, but it was with the verses of ‘Childe Harold’, published on his return, that he not only made his own name but cast this old Philhellenism into the form that was to galvanize Romantic Europe into action.

Oh, thou, Parnassus! whom I now survey,

Not in the phrensy of a dreamer’s eye,

Not in the fabled landscape of a lay,

But soaring snow-clad through thy native sky,

In the wild pomp of mountain majesty!

What marvel if I thus essay to sing?

The humblest of the pilgrims passing by

Would gladly woo thine Echoes with his string,

Though from thy heights no more one Muse will wave her wing.

Fair Greece! sad relic of departed worth!

Immortal, though no more; though fallen, great!

Who now shall lead thy scatter’d children forth,

And long accustom’d bondage uncreate?

Not such thy sons who whilome did await,

The hopeless warriors of a willing doom,

In bleak Thermopylae’s sepulchral strait –

Oh! who that gallant spirit shall resume,

Leap from Eurotas’ banks, and call thee from the tomb?

Where’er we tread ’tis haunted, holy ground;

No earth of thine is lost in vulgar mould,

But one vast realm of wonder spreads around,

And all the Muse’s tales seem truly told,

Till the sense aches with gazing to behold

The scenes our earliest dreams have dwelt upon;

Each hill and dale, each deepening glen and wold

Defies the power which crush’d thy temples gone:

Age shakes Athena’s tower, but spares gray Marathon.33

There is not an idea here that was new – not an idea of any sort it could be argued – but faced with verses of this power it is as idle to think of Byron as a product of Philhellenism as it is to see Shakespeare as a mere child of the Elizabethan Renaissance. The excitement and sentiments displayed were certainly no more Byron’s invention than was the ‘Byronic hero’, and yet in ‘Childe Harold’ and his Eastern Tales he succeeded in setting the stamp of his personality on a whole movement, giving it a new and popular currency and charting the emotional and topographical map-references from which Philhellenism has never tried to escape.

It is not simply that there is no figure in Philhellene history to compare with Byron, there is no second to him. What we are looking at in the verses of ‘Childe Harold’ or ‘Don Juan’ is some kind of literary take-over, at a whole disparate, woolly and amorphous movement captured and vitalized by the specific genius of one man. Before Byron, it is safe to say, for all its seriousness, its achievements, its intelligence, there was no folly of which western Philhellenism was incapable: after Byron, for all its romantic froth, there was nothing to which it would not aspire.

The mountains look on Marathon –

And Marathon looks on the sea;

And musing there an hour alone,

I dream’d that Greece might still be free;34

The history of the Philhellene movement is so impossible to imagine without Byron that it always comes as a surprise to remember that for almost three years of the war his involvement remained no more than this ‘dream’. On the outbreak of rebellion in 1821, he had returned to the theme of Greek freedom with some of the most famous lyrics in ‘Don Juan’ and, again, in the following year, there had been some desultory talk of volunteering, but his letters for this period – for the years that Trelawny knew him – are the letters of a man submerged in a life of literary and social affairs that left little room for Greece. It was a life full of gossip and flirtations, of boats, business and his mistress, Teresa Guiccioli, of Italian politics and proof-reading, of arguments about Pope and the deaths of Shelley and Keats, of Leigh Hunt’s financial affairs and repulsive children, of rows with his publisher Murray and over Allegra, of Lady Byron and his half-sister Augusta – a life at once so full and empty as to be much like any other except that it was lived out by Byron. In 1823 Byron could as easily have gone to Spain as Greece; or Naples, or South America, or a South Sea Island, or nowhere at all. Chance, pique, sloth, lust, avarice, good nature and pride might still have disposed of him in any of a dozen ways that summer: only myth pushes him towards Greece with a confidence that will brook no dissent.

Given how much was at stake there is something alarming in the precariousness of this historical process, in its casual and arbitrary shedding of options until all that was left was the brittle chain of events that in 1823 lead Byron from Italy to Missolonghi. During the months that Trelawny chafed impatiently at his irresolution, the London Greek Committee had done all it could to flatter and cajole Byron into a proper sense of his destiny, and yet it remains as hard to define what it was that finally stirred him to action as it is for the most obscure volunteer whose name is alongside his on that Nauplia monument.

It is tempting to think, in fact, that there is no one about whom so much was said and written and about whom we know so little as the figure on whom Trelawny and all Philhellene Europe waited that summer. A generation before Byron, Boswell’s Johnson had been the object of the same obsessive interest to his circle, but between the two men something had happened – some permanent and vulgarizing shift in the popular conception of the artist – that the Byron myth both lived off and fed.

The minutiae of Johnson’s life seemed of value to Boswell because, with the instinct of genius, he knew that they revealed the inner man. With Byron the details were all that mattered, valuable by a simple process of association, the raw material of an indiscriminate and insatiable curiosity which set the pattern for all future fame. Nobody it seems, at this time, met Byron without recording their impressions. Nothing, either, was too small to be saved for posterity. We know then the state of the Cheshire cheese he ate and the manufacturer of his ale, the colour and trimming of his jacket, the style of his helmet and every last detail of the bizarre retinue of servants, horses and dogs that he collected in preparation for war: what remains a mystery is the lonely process by which he came to terms with the realities of his commitment to the Greek cause.

It is more than likely that he did not know himself. Certainly his letters – flippant, self-deprecating, brilliant, but ultimately elusive – give nothing away. Byron was far too intelligent to indulge in the inflated expectations of so many Philhellenes, only too aware of Greek attitudes and of his own limitations. He had enjoyed and suffered far too much fame to need to find it in Greece. He was thirty-six years old, though sixty in spirit, as he had been claiming on and off since 1816. He was, since the collapse of his disastrous marriage seven years earlier, an exile. He was a poet writing the greatest poetry of his life, but conscious too of a world of action that held an irresistible fascination. He was an aristocrat alert to his status, and a liberal conscious of his moral duties. He was, above all, half reluctantly, indolently, but inescapably, the repository of the expectations of an age he had done so much to shape – expectations which carried with them a burden that took on all the heaviness of fate: ‘Dear T.,’ he finally wrote to Trelawny in June: ‘you may have heard that I am going to Greece. Why do you not come with me?… they all say that I can be of use in Greece. I do not know how, nor do they; but at all events let us go.’35

It was the letter for which Trelawny had been waiting – for months certainly, possibly all his life. On 26 June, he wrote to his old friend Daniel Roberts from Florence.

Dear Roberts,

Your letter I have received and one from Lord Byron. I shall start for Leghorn to-morrow, but must stop there some days to collect together the things necessary for my expedition. What do you advise me to do? My present intention is to go with as few things as possible, my little horse, a servant, and two very small saddle portmanteaus, a sword and pistols, but not my Manton gun, a military frock undress coat and one for superfluity, 18 shirts, &. I have with me a Negro servant, who speaks English – a smattering of French and Italian, understands horses and cooking, a willing though not a very bright fellow. He will go anywhere or do anything he can, nevertheless if you think the other more desirable, I will change – and my black has been in the afterguard of a man of war. What think you?

I have kept all the dogs for you, only tell me if you wish to have all three. But perhaps you will accompany us. All I can say is, if you go, I will share what I have freely with you – I need not add with what pleasure!… How can one spend a year so pleasantly as travelling in Greece, and with an agreeable party?36

The next day, on the road to Leghorn, there was a more difficult letter to write.

Dearest Clare,

What is it that causes this long and trying silence? – I am fevered with anxiety – of the cause – day after day I have suffered the tormenting pains of disappointment – tis two months nearly since I have heard. What is the cause, sweet Clare? – how have I newly offended – that I am to be thus tortured? –

How shall I tell you, dearest, or do you know it – that – that – I am actually now on my road – to Embark for Greece? – and that I am to accompany a man that you disesteem? [‘Disesteem’ to one of the century’s great haters!] – forgive me – extend to me your utmost stretch of toleration – and remember that you have in some degree driven me to this course – forced me into an active and perilous life – to get rid of the pain and weariness of my lonely existence; – had you been with me – or here – but how can I live or rather exist as I have been for some time? – My ardent love of freedom spurs me on to assist in the struggle for freedom. When was there so glorious a banner flying as that unfurled in Greece? – who would not fight under it? – I have long contemplated this – but – I was deterred by the fear that an unknown stranger without money &. would be ill received. – I now go under better auspices – L.B. is one of the Greek Committee; he takes out arms, ammunition, money, and protection to them – when once there I can shift for myself – and shall see what is to be done!37

The implied urgency in Trelawny’s letters, their sense of bustle and importance, was for once justified. Now that Byron had made up his mind, he moved quickly. The Bolivar was sold, and his Italian affairs brought into order. He had engaged a vessel, the Hercules, he told Trelawny, and would be sailing from Genoa. ‘I need not say,’ he added, ‘that I shall like your company of all things,’ – a tribute he was movingly to repeat in a last footnote to Trelawny in a letter written only days before his death.38

Travelling on horseback from Florence to Lerici, where he wandered again through the desolate rooms of Shelley’s Casa Magni, Trelawny reached Byron at the Casa Saluzzi, near Albaro. The next day he saw the Hercules for the first time. To the sailor and romantic in him it was a grave disappointment. To Byron, however, less in need of exotic props than his disciple, the collier-built tub – ‘roundbottomed, and bluff bowed, and of course, a dull sailor’39 – had one estimable advantage. ‘They say’, he told Trelawny, ‘I have got her on very easy terms … We must make the best of it,’ he added with ominous vagueness. ‘I will pay her off in the Ionian Islands, and stop there until I see my way.’40

On 13 July 1823, horses and men were loaded on board the Hercules, and Trelawny’s long wait came to an end. Ahead of him lay a life he had so far only dreamed of, but he was ready. The war out in Greece might have been no more than ‘theatre’ to him, yet if there was anyone mentally or emotionally equipped to play his role in the coming drama, anyone who had already imaginatively made the part his own, then it was Trelawny.

Over the last eighteen months too, he had grown into his role, grown in confidence, in conviction, in plausibility. At the beginning of 1822 Byron had announced Trelawny’s arrival to Teresa Guiccioli with a cool and ironic amusement: by the summer of 1823 he had become an essential companion.

And now, too, as the Hercules ploughed through heavy waters on the first stage of its journey south, all the landmarks that had bound Trelawny to the Pisan Circle slipped past in slow review as if to seal this pact: Genoa, where the Don Juan had been built for Shelley to Trelawny’s design – ‘the treacherous bark which proved his coffin,’41 as he bitterly described it to Claire Clairmont; St Terenzo, with the Casa Magni, Shelley’s last house, set low on the sea’s edge against a dark backdrop of wooded cliffs; Viareggio where he and Byron had swum after Williams’s cremation until Byron was sick with exhaustion; Pisa where they had first met at the Palazzo Lanfranchi, and finally Leghorn, from where almost exactly a year earlier, Shelley, Edward Williams and the eighteen-year-old Charles Vivian – one of Romanticism’s forgotten casualties – had set out on their last voyage.

It was on the fifth day out of Genoa, and only after a storm had driven them back into port, that the Hercules finally made Leghorn. Byron had business ashore, and some last letters to write – a three-line note to Teresa Guiccioli, assuring her of his love, and a rather more fulsome declaration of homage to Goethe, ‘the undisputed Sovereign of European literature’.42 On 23 July they were ready to sail again, and took on board two dubious Greeks and a young Scotsman, Hamilton Browne, who had served in the Ionian Isles. Browne was rowed out to the ship by a friend, the son of the Reverend Jackson who had famously poisoned himself during the Irish troubles to thwart justice. Byron recognized the name and was quick with his sympathy. ‘His lordship’s mode of address,’ Browne wrote of this first meeting, ‘was peculiarly fascinating and insinuating – “au premier abord” it was next to impossible for a stranger to refrain from liking him.’43

Byron, however, was going to need more than charm to survive the months ahead as their brief stop in Leghorn underlined. While the Hercules was still in the roads, he wrote a final letter to Bowring, the Secretary of the London Greek Committee to which he had been elected, striking in it a note that can be heard again and again in his subsequent letters from Greece. ‘I find the Greeks here somewhat divided amongst themselves’, he reported,

I have spoken to them about the delay of intelligence for the Committee’s regulation – and they have promised to be more punctual. The Archbishop is at Pisa – but has sent me several letters etc. for Greece. – What they most seem to want or desire is – Money – Money – Money … As the Committee has not favoured me with any specific instructions as to any line of conduct they might think it well for me to pursue – I of course have to suppose that I am left to my own discretion. If at any future period – I can be useful – I am willing to be so as heretofore. –44

The punctuation of Byron’s letters invariably gives a strong sense of rapidity and urgency of thought, an immediacy that makes him one of the great letter writers in the language, and yet curiously here it only serves to reinforce a sense of uncertainty and drift. It is a feeling that seems mirrored in the mood on the Hercules as each day put his Italian life farther behind him. There is an air of unreality about this journey, as if the Hercules and its passengers were somehow suspended between the contending demands of past and future, divorced from both in the calm seas that blessed the next weeks of their passage. It is hard to believe that, for all his clear-eyed and tolerant realism about the Greeks, Byron had any real sense of what lay ahead. The memory of Shelley’s corpse on the beach could quicken his natural fatalism into something like panic at the thought of pain but even this was a passing mood. As Trelawny later recalled, he had never travelled on ship with a better companion. The weather, after they left Leghorn, was beautiful and the Hercules seldom out of sight of land. Elba, the recent scene of Napoleon’s first exile, was passed off the starboard bow with suitable moralizings. At the mouth of the Tiber the ship’s company strained in vain for a glimpse of the city where Trelawny had buried Shelley’s ashes and prepared his own grave. During the day Byron and Trelawny would box and swim together, measure their waistlines or practise on the poop with pistols, shooting the protruding heads off ducks suspended in cages from the mainyard. At night Byron might read from Swift or sit and watch Stromboli shrouded in smoke and promise another canto of ‘Childe Harold’.

And yet Byron, if he ever had been, was no longer the ‘Childe’ and in that simple truth lay a world of future misunderstandings. One of the most moving aspects of his last year is the way his letters and actions reveal a gradual firming of purpose, a steady discarding of the conceits and fripperies of his Italian existence, a unifying of personality, an alignment at last of intelligence and sensibility – a growth into a human greatness which mirrors the development of his literary talents from the emotional and psychological crudity of ‘Childe Harold’ into the mature genius of ‘Don Juan’.

For anyone interested in poetry it is in that last masterpiece that the real Byron is to be found, but it was not the Byron that Trelawny had come to Italy in search of. Even before the Hercules had left Leghorn he was airing his reservations in letters to Roberts and Claire, but the fact is that his unease in Byron’s company was as long as their friendship itself. Eighteen months earlier, in January 1822, Trelawny had come looking for Childe Harold and found instead a middle-aged and worldly realist. He had come to worship and found a deity cynically sceptical of his own cult. ‘I had come prepared to see a solemn mystery,’ he wrote of their first meeting in the Palazzo Lanfranchi, ‘and so far as I could judge from the first act it seemed to me very like a solemn farce.’45

One of the great truisms of Romantic history is that Byron was never ‘Byronic’ enough for his admirers but this failure to live up to expectations seems to have constituted a more personal betrayal for Trelawny than it did for other acolytes. In trying to explain this there is a danger of ignoring the vast intellectual gap which separated the two men, yet nevertheless something is needed to account for the resentment which, even as they set off together, he was stoking up against Byron. Partly, of course, it was the bitterness of the disappointed disciple, but there was something more than that, something which Romantic myth and twentieth-century psychology in their different ways both demand to be recognized – the rage of the creature scorned in the language of one, of childhood rejection in the more prosaic terminology of the other.

The moment words are put to it they seem overblown and lame by turns but it is impossible to ignore the evidence of a lifetime’s anger. No iconoclast ever had such a capacity for hero-worship as Trelawny and, of the long string of real or imagined figures who filled the emotional vacuum of a loveless childhood, Byron was the earliest and the greatest. In among the fantasies that Trelawny published as his Adventures, there is a description of his first meeting with the mythical De Ruyter, the imagined archetype and amalgam of all Trelawny’s heroes. It gives a vivid insight into what he had sought in Byron when he first came to Italy. ‘He became my model,’ he wrote,

The height of my ambition was to imitate him, even in his defects. My emulation was awakened. For the first time I was impressed with the superiority of a human being. To keep an equality with him was unattainable. In every trifling action he evinced a manner so offhand, free, and noble, that it looked as if it sprung new and fresh from his own individuality; and everything else shrunk into an apish imitation.46

This kind of hero, however, was not a role that the thirty-five-year old Byron, with his anxieties over his weight or the thickness of his wrists, had either the inclination or temperament to fill. The helmets and uniforms in his luggage are reminders that, even in his last year, the exhibitionist in him was never entirely stilled, but the irony and self-mockery with which he treated himself in his poetry was now equally, if humorously, turned on his ‘corsair’. Trelawny, he memorably remarked, could not tell the truth even to save himself. In another variant on this he suggested that they might yet make a gentleman of him if they could only get him to tell the truth and wash his hands.

For a man who was probably only too familiar with Trelawny’s battle against his father’s pet raven, this was a dangerously cavalier attitude to take to the child of his poetic imagination. ‘The Creator’, as Claire had warned Byron in her first letter to him before they met, ‘ought not to destroy his Creature.’47 For a man, also, who in Pisan lore had been responsible for the death of Claire’s Allegra, this was doubly true. Byron was too careless, however, to see the trouble he was laying down. On board the Hercules a mixture of his own tolerance and Trelawny’s presumption kept relationships cordial, but it was a deceptive calm. ‘Lord B. and myself are extraordinarily thick,’ Trelawny wrote edgily to his friend Roberts in a letter from Leghorn.

We are inseparable. But mind, this does not flatter me. He has known me long enough to know the sacrifices I make in devoting myself to serve him. This is new to him, who is surrounded by mercenaries. I am no expense to him, fight my own way, lay in my own stock, etc … Lord B. indeed does everything as far as I wish him.’48

It was a sad delusion but it was enough to preserve the peace of the voyage. At the toe of Italy the Hercules turned east, through the Messina Straits and towards Greece. Their first destination was the port of Argostoli on Cephalonia, one of the Ionian Isles under British control. As they passed through the untroubled waters between Scylla and Charybdis, Byron complained of the tameness of life. His boredom was premature. His and Trelawny’s lives were moving to their distinct but inseparable crises. ‘Where’, Byron had mused at Leghorn, ‘shall we be in a year?’ It afterwards seemed to Pietro Gamba, Teresa Guiccoli’s brother, ‘a melancholy foreboding; for on the same day of the same month, in the next year, he was carried to the tomb of his ancestors.’49 On 2 August 1823, the Hercules entered the approaches to Argostoli. Byron had just nine months to live: Trelawny, nearly sixty years to vent his feelings against the man who had first created and then wearied of him.