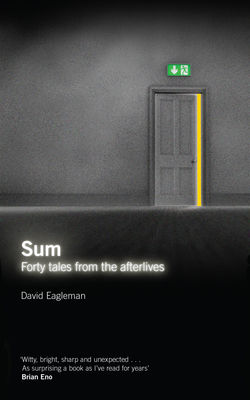

Читать книгу Sum - David Eagleman - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Mary

ОглавлениеWhen you arrive in the afterlife, you find that Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley sits on a throne. She is cared for and protected by a covey of angels.

After some questioning, you discover that God’s favorite book is Shelley’s Frankenstein. He sits up at night with a worn copy of the book clutched in His mighty hands, alternately reading the book and staring reflectively into the night sky.

Like Victor Frankenstein, God considers Himself a medical doctor, a biologist without parallel, and He has a deep, painful relationship with any story about the creation of life. He has much to say about bringing animation to the unanimated. Very few of His creatures had thought deeply about the challenges of creation, and it relieved Him a little of the loneliness of His position when Mary wrote her book.

The first time He read Frankenstein, He criticized it the whole way through for its oversimplification of the processes involved. But when He reached the end He was won over. For the first time, someone understood Him. That’s when He called for her and put her on a throne.

To understand His outpouring of feeling, you must understand the trajectory of God’s medical career. God discovered the principles of self-organization by experimenting with yeast and bacteria. He reveled in the beauty of His inventions. Once He mastered the general principles, His inventions became increasingly sophisticated. With artistic flair He sewed together the astounding platypus, the compact beetle, the weighty woolly mammoth, the glistening pods of dolphins. His skills became razor-sharp and keen, and His accurate fingers fashioned—with blinding ambitious accuracy—all the animals at the limits of His vast imagination.

But then, unwittingly, He crossed His Rubicon. He created Man: His most prized possession, His treasure, pride, showpiece, and obsession.

Unlike the other animals, who experienced each day like the one before, Man cared, sought, yearned, erred, coveted, and ached—just like God Himself.

He marveled as Man picked through the ground and formed tools. The invention of musical instruments reached God’s ears like a symphony. He watched with awe as men gathered up, erected cities, built walls. He felt His joy turn to trepidation as they began to scrap and brawl. It didn’t take long before they were invading. Wars waged as He tried to talk sense to those who might listen.

He quickly discovered He had less control than He thought. There were simply too many of them. He tried to make good things come to good people, and bad to bad, but He didn’t have the technology to implement it. The bloodshed mounted and was carried forward by the Assyrians and Babylonians; the Greco-Macedonians assailed their neighbors; the Romans began their onslaught until the sieges of Barbarians and Goths. Byzantium rose and fell in blood; the Chinese baited and pounced; Europeans flung themselves at each other. The bright colors of His ground were darkening with Man’s blood, and there was precious little He could do to stop it.

And all throughout, the voices of Man reached Him with pleas for help, entreaties for aid against one another. He plugged His ears and howled against the cries of pillaged villages, the prayers of exsanguinating soldiers, the supplications from Auschwitz.

This is why He now locks Himself in His room, and at night sneaks out onto the roof with Frankenstein, reading again and again how Dr. Victor Frankenstein is taunted by his merciless monster across the Arctic ice. And God consoles Himself with the thought that all creation necessarily ends in this: Creators, powerless, fleeing from the things they have wrought.