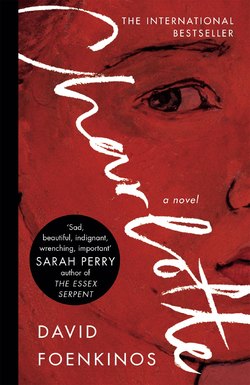

Читать книгу Charlotte - David Foenkinos - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPart Two

1

When she hears the news, Charlotte says nothing.

A violent attack of flu has taken her mother.

She thinks about that word: flu.

One word and it’s all over.

Years later, she will finally learn the truth.

In an atmosphere of general chaos.

For now, she comforts her father.

It’s all right, she says.

Mama told me about this.

She has become an angel.

She always said how wonderful it is in heaven.

Albert does not know how to respond.

He wants to believe this too.

But he knows the truth.

His wife has left him.

Alone, with their daughter.

Everywhere he goes, memories haunt him.

In every room, through every object, she is there.

The air in the apartment is the same air she breathed.

He wants to rearrange the furniture, smash it all up.

Or, better still, move to a new house.

But when he speaks to Charlotte about this, she refuses.

Her mother promised to send her a letter.

Once she is up in heaven.

So they have to stay here.

Otherwise mama won’t be able to find us, says the little girl.

Each evening, she waits for hours.

Sitting on the window ledge.

The horizon is dark, gloomy.

Perhaps that is why her mother’s letter has not found its way here.

Days pass, without any news.

Charlotte wants to go to the cemetery.

She knows every inch of it.

She walks up to her mother’s gravestone.

Don’t forget your promise: you have to tell me everything.

But still nothing.

Nothing.

This silence, she can’t stand it anymore.

Her father tries to reason with her.

The dead cannot write to the living.

And it’s better that way.

Your mother is happy, up there.

There are lots of pianos hidden in the clouds.

What he says doesn’t make much sense.

His thoughts get tangled up.

Finally, Charlotte understands there will be no letter.

She is terribly angry with her mother.

2

Now, it is time to learn solitude.

Charlotte does not share his feelings.

Her father hides in his work, buries himself in it.

Every evening, he sits at his desk.

Charlotte watches him, stooped over his books.

Piles of books, high as towers.

Mad-eyed, he mumbles all sorts of formulas.

Nothing can block his progress on the path to knowledge.

Nor on the path to renown.

He has just been given a professorship at the medical faculty in Berlin.

It is a consecration, a dream.

Charlotte does not seem very happy about it.

In truth, it has become difficult for her to express any emotion.

At the Fürstin-Bismarck school, people whisper as she passes.

They must be kind to her, her mama is dead.

Her mama is dead, her mama is dead, her mama is dead.

Thankfully, the building is comforting, with its wide stairways.

A place where pain is soothed.

Charlotte is happy to go there every day.

I took the same walk myself.

Many times, following in her footsteps.

There and back, in search of Charlotte as a child.

One day, I went inside the school.

Girls were running through the lobby.

I thought that Charlotte could still be among them.

At the front office, I was welcomed by the academic counselor.

A very affable woman named Gerlinde.

I explained to her the reason I was there.

She did not seem surprised.

Charlotte Salomon, she repeated to herself.

We know who she is, of course.

. . .

So began a long visit.

Meticulous, because every detail matters.

Gerlinde talked up the virtues of the school.

Observing my reactions, my emotions.

But the most important was yet to come.

She suggested I go to see the biology equipment.

Why?

Because none of it has changed.

It is like diving into the last century.

Diving into Charlotte’s world.

We walked through a dark, dusty corridor.

And came to an attic full of stuffed animals.

And insects spending eternity inside a jar.

A skeleton caught my eye.

Death, the ceaseless refrain of my quest.

Charlotte must have studied it, Gerlinde announced.

I was there, almost a century after my heroine.

Analyzing, in my turn, the form of a human body.

At the end, we visited the beautiful auditorium.

A group of girls was posing for the class photo.

Encouraged by the photographer, they were goofing around.

A successful attempt to immortalize the joy of living.

I thought of Charlotte’s class photo, which I had seen before.

It was not taken in this room, but in the schoolyard outside.

It is a deeply disturbing picture.

All the girls stare into the lens.

All of them, but one.

Charlotte’s eyes are turned in a different direction.

What is she looking at?

3

Charlotte lives with her grandparents for a while.

She stays in her mother’s childhood bedroom.

This confuses the grandmother.

She gets her eras mixed up.

A child with the face of her first daughter.

A child with the same name as her second.

In the night, fearful, she gets up several times.

She has to check that little Charlotte is sleeping peacefully.

The girl grows wild.

Her father hires nannies and she does all she can to drive them to despair.

She hates anyone who tries to take care of her.

Worst of the bunch: Miss Stagard.

A stupid, vulgar woman.

Charlotte is the most badly brought-up girl she has ever known, she says.

Thankfully, on an outing one day, she falls into a crevasse.

She screams with pain, her leg broken.

Charlotte is in seventh heaven, finally rid of her.

But with Hase, everything is different.

Charlotte loves her instantly.

As Albert is never home, Hase practically lives there.

When she washes, Charlotte gets up to spy on her.

She is fascinated by the size of her breasts.

It is the first time she has seen such big ones.

Her mother’s were small.

What about hers: what will they be like?

She would like to know what is preferable.

On the apartment landing she sees a neighbor boy her own age, and asks him.

He seems very surprised.

Then finally answers: large breasts.

So Hase is lucky, but she isn’t very pretty.

Her face is a little puffy.

And she has hairs on her upper lip.

In fact, you could probably call it a moustache.

So Charlotte goes back to see her neighbor.

Is it better to have large breasts and a moustache . . .

Or small breasts with the face of an angel?

The boy hesitates again.

In a serious voice, he replies that the second solution seems better to him.

Then he walks away without another word.

After that, he will always be embarrassed when he sees the strange girl next door.

As for Charlotte, she feels relieved by this response.

Deep down, she is pleased that men do not like Hase.

She loves her too much to risk losing her.

She doesn’t want anyone to love her.

Nobody but her.

4

It is the first Christmas without her mother.

Her grandparents are there, colder than ever.

The Christmas tree is immense, too big for the living room.

Albert bought the biggest and most beautiful one he could find.

For his daughter, naturally, but also in memory of his wife.

Franziska adored Christmas.

She would spend hours decorating the tree.

It was the highlight of her year.

The tree is dark now.

As if it, too, were in mourning.

Charlotte opens her presents.

They are watching her, so she plays the role of the happy girl.

A little theater to lighten the moment.

To dispel her father’s sadness.

Silence is what hurts most of all.

At Christmas, her mother used to sit at the piano for hours.

She loved Christian hymns.

Now the evening passes without a single melody.

Charlotte often looks at the piano.

She is incapable of touching it.

She can still see her mother’s fingers on the keyboard.

On this instrument, the past is alive.

Charlotte has the feeling that the piano can understand her.

And share her wound.

The piano is like her: an orphan.

Every day, she stares at the open sheet music.

The last piece her mother ever played.

A Bach concerto.

Several Christmases will pass this way, in silence.

5

It is now 1930.

Charlotte is a teenager.

People like to say that she is in her own world.

Being in one’s own world, where does that lead?

To daydreams and poetry, undoubtedly.

But also to a strange mix of disgust and bliss.

Charlotte can smile and suffer at the same time.

Only Hase understands her, and it happens without words.

In silence, Charlotte rests her head on the nanny’s chest.

Like that, she feels listened to.

Some bodies are consolations.

But Hase no longer spends so much time looking after Charlotte.

Albert says a thirteen-year-old girl has no need for a nanny.

Does he have any idea what his daughter wants?

If that’s how it is, she refuses to grow up.

Charlotte feels ever more alone.

Her best friend is now spending more time with Kathrin.

A new pupil in the school, and already so popular.

How does she do it?

Some girls have the gift of making others love them.

Charlotte is afraid of being abandoned.

The best solution is to avoid becoming attached.

Because nothing lasts.

She must protect herself from potential disappointments.

But no, that’s ridiculous.

She can see what’s happening to her father.

By separating himself from other people, he has become a gray man.

So she encourages him to go out.

During one dinner party, he finds himself talking to a famous opera singer.

She has just made a record, and it’s wonderful.

All over Europe, people are praising it.

She also sings in churches: sacred music.

Albert is tongue-tied, intimidated.

The conversation is full of silences.

If only she was ill, the doctor would know what to say.

Alas, this woman is in sickeningly good health.

After a while, he stammers that he has a daughter.

Paula (that’s her name) is charmed by this.

Chased constantly by admirers, she dreams of a man who is not an artist.

Kurt Singer, the dashing Opera House director, idolizes her.

He wants to give up everything for her (his wife, in other words).

His wooing borders on harassment.

For months, he has been promising Paula the earth.

A neurologist too, he helps women with nervous problems.

To cast a spell on her, he even tries hypnosis.

Paula starts to yield, then pushes him away.

One night, coming out of a concert, Kurt’s wife suddenly appears.

Desperate, she throws a vial of poison at Paula.

Poison that she probably thought about swallowing.

A tragic love story.

This incident leaves Paula weak.

She decides it is time she got married.

To put an end to this exhausting situation.

In this context, Albert seems to her like a refuge.

Anyway, she prefers the surgeon’s hands.

Albert tells Charlotte about his meeting with Paula.

Thrilled, she insists that he invite her to dinner.

It would be such an honor.

He obeys.

On the evening in question, Charlotte wears her best dress.

The only one she likes, in truth.

She helps Hase prepare the table and the meal.

Everything must be perfect.

At eight o’clock, the doorbell rings.

Eagerly, she rushes to open it.

Paula gives her a big smile.

You must be Charlotte, says the opera singer.

Yes, that’s me, she wants to reply.

But no sound emerges.

The meal passes in an atmosphere of muted joy.

Paula invites Charlotte to see her in concert.

And afterward, you can visit my dressing room.

You’ll see, it’s very beautiful, Paula adds.

Backstage is the only place where the truth exists.

She speaks softly, her voice so fine.

There is nothing diva-like about her.

On the contrary, there is a delicacy to her gestures.

Everything is going wonderfully, thinks Albert.

It’s as if Paula had always lived here.

After dinner, they beg her to sing.

She approaches the piano.

Charlotte’s heart is no longer beating—it is pounding.

Paula leafs through the sheet music next to the piano.

Finally she chooses a Schubert lied.

And places it over the Bach.

6

Charlotte cuts out every article about Paula.

It fascinates her, that one person can be so loved.

She loves hearing the applause in the concert hall.

She is proud that she knows the artist personally.

Charlotte basks in the audience’s enthusiasm.

The noise of admiration is fabulous.

Paula shares with her the love she receives.

She shows Charlotte the flowers and the letters.

All of this takes the form of a strange consolation.

Life becomes richer, goes faster.

Suddenly everything seems frenetic.

Albert asks his daughter what she thinks of Paula.

I simply adore her.

Well, that’s perfect, because we’ve decided to get married.

Charlotte throws her arms round her father’s neck.

Something she hasn’t done for years.

The wedding takes place in a synagogue.

Raised by her rabbi father, Paula is a true believer.

Judaism has had little importance in Charlotte’s life.

One might even say: none at all.

Her childhood is based around an absence of Jewish culture.

In the words of Walter Benjamin.

Her parents lived a secular life.

And her mother loved Christian hymns.

At thirteen, Charlotte is discovering this world that is supposedly hers.

She observes it with that easy curiosity we have for things that seem distant to us.

7

Albert’s new wife moves to 15 Wielandstrasse.

Charlotte’s life is turned upside down.

The apartment, long used to emptiness and silence, is transformed.

Paula brings the cultural life of Berlin into their home.

She invites celebrities.

They meet the famous Albert Einstein.

The architect Erich Mendelsohn.

The theologian Albert Schweitzer.

This is the zenith of German domination.

Intellectual, artistic and scientific.

They play the piano, they drink, they sing, they dance, they invent.

Life has never seemed so intense.

There are now little brass plaques on the ground outside this address.

These are Stolpersteine.

Tributes to the victims of the Holocaust.

There are many of them in Berlin, especially in Charlottenburg.

They are not easy to spot.

You must walk with your head down, seeking memories between the cobblestones.

In front of 15 Wielandstrasse, three names can be read.

Paula, Albert and Charlotte.

But on the wall, there is only one commemorative plaque.

The one for Charlotte Salomon.

During my last visit to Berlin, it had vanished.

The building was being renovated, under scaffolding.

Charlotte erased for a fresh coat of paint.

Sanitized, the house façade looks like a movie backdrop.

Immobile on the sidewalk, I stare at the balcony.

Where Charlotte posed for a photograph with her father.

The picture was taken around 1928.

She is eleven or twelve, and the look in her eyes is bright.

She already looks surprisingly like a woman.

I dally for a moment in the past.

Preferring to look at the photograph in my memory rather than the present.

Then, finally, I make a decision.

I weave between the ladders and the workmen and go upstairs.

To the second floor, outside her apartment.

I ring Charlotte’s doorbell.

Because of the construction work, the place is empty.

But there is a light on in the apartment.

As if someone’s there.

There must be someone there.

And yet I hear no sound.

It’s a large apartment, I know.

I ring again.

Still nothing.

While I wait, I read the names listed above the doorbell.

Apparently the Salomons’ apartment has been turned into offices.

The company headquarters of Dasdomainhaus.com.

A firm that develops websites.

I hear a noise.

Footsteps coming closer.

Someone hesitating, then opening the door.

A worried-looking woman appears.

What do we want?

Christian Kolb, my German translator, is with me.

He takes his time before speaking.

Dot dot dot is always in his mouth.

I ask him to explain why we are here.

French writer . . . Charlotte Salomon . . .

She slams the door in our faces.

I stand there stunned, immobile.

I am only a few feet from Charlotte’s room.

It’s frustrating, but some things should not be forced.

I have plenty of time.

8

Charlotte is enriched by the discussions she hears.

She starts reading: a lot, and with passion.

Devours Goethe, Hesse, Remarque, Nietzsche, Döblin.

Paula thinks her stepdaughter is too withdrawn.

She never invites friends home.

Charlotte becomes possessive with her stepmother.

During parties, she follows her around like a shadow.

Cannot bear other people to spend too long talking to her.

She wants to give Paula something special for her birthday.

She spends whole days searching for the ideal gift.

Finally, she finds the perfect powder compact.

All her pocket money goes toward it.

She is so pleased with her find.

Her stepmother will love her even more.

The evening of the birthday, Charlotte is on tenterhooks.

Paula opens her present.

She is very happy with it.

But it is one gift among many.

She thanks everyone with equal sweetness.

Charlotte falls to pieces.

She is crushed by the disappointment.

Driven crazy.

She rushes over to grab back the compact.

And hurls it on the floor, in front of all the guests.

Silence descends.

Albert looks at Paula, as if it is up to her to react.

The singer is coldly furious.

She accompanies Charlotte to her room.

We’ll talk about this tomorrow, she says.

I’ve ruined everything, thinks Charlotte.

In the morning, they see each other in the kitchen.

Charlotte starts babbling excuses.

She tries to explain what she was feeling.

Paula strokes her cheek, to comfort her.

Glad that Charlotte is finally able to put words to her malaise.

Paula remembers the joyful adolescent she met.

She doesn’t understand what it is that troubles her so much now.

For Albert, his daughter’s reaction is a manifestation of jealousy.

Nothing more.

He refuses to see the depth of her suffering.

His work takes up all his attention; he is an important doctor.

He is making major discoveries in the treatment of ulcers.

His daughter’s tantrums are not his priority.

Paula continues to worry.

She thinks Charlotte should be told everything.

The truth.

What truth? Albert asks.

The truth . . . about her mother.

She insists.

No one can build their identity on such a lie.

If she finds out that everyone has lied to her, it will be awful.

No, Albert replies, we must say nothing about it.

Then adds: her grandparents are adamant.

They do not want her to know.

Paula suddenly understands.

Charlotte often goes to stay at their house.

The pressure is incessant.

They never let anyone forget that they have lost their daughters.

Lotte is all that’s left to them, they moan.

When she returns from staying with them, Charlotte is somber.

Her grandmother loves her very deeply, of course.

But there is a dark power to her love.

How can that woman look after a child?

That woman whose two daughters killed themselves.

9

Paula agrees not to reveal anything to Charlotte.

As that is the family’s wish.

But she sends a scathing letter to the grandmother.

“You are the murderer of your daughters.

But this time you won’t have her.

I am going to protect her . . .”

Devastated, the grandmother withdraws into herself.

The past she attempted to bury is coming back in waves.

She lets the successive tragedies overwhelm her.

There are her two daughters, of course.

But they are only the culmination of a long line of suicides.

Her brother too threw himself in a river, because of an unhappy marriage.

A doctor of law, he was only twenty-eight.

His corpse was exhibited in the living room.

For days on end, the family slept close to the tragedy.

They didn’t want to let him leave.

The apartment would be his tomb.

Only the stink of decomposition put an end to the exhibition.

When they came to pick up her son, the mother tried to stop them.

She could accept his death, not his absence.

Not the absence of his body.

She sank into insanity.

Two full-time nurses were hired.

To protect her from herself.

As would later happen to Franziska, just after her first suicide attempt.

So history would repeat itself.

Repeat itself endlessly, like the refrain of the dead.

The grandmother remembers such difficult years.

When she had to constantly watch her own mother.

She would speak to her sometimes to soothe her.

This seemed to calm her down.

But inevitably she started mentioning her son again.

She said he was a sailor.

That was why they didn’t see much of him.

And then suddenly the reality would hit her in the face.

It would bite, hard.

And she would scream for hours.

After eight years of mental exhaustion, she finally succumbed.

Perhaps the family would be able to find a semblance of peace.

But it wasn’t over for Charlotte’s grandmother.

No sooner was their mother in the ground than her younger sister committed suicide.

Inexplicably, unforeseeably.

At eighteen years old, she got up in the night.

And threw herself in the icy river.

Just as the first Charlotte would do later.

So history would repeat itself.

Repeat itself endlessly, like the refrain of the dead.

The grandmother had been paralyzed by her sister’s death.

She had not seen it coming—and nor had anyone else.

She had to get away, fast.

Marriage was the best option.

She became a Grunwald.

And quickly had two daughters.

. . .

A few years passed, strangely happy.

But the black march began again.

Her brother’s only daughter committed suicide.

And then it was her father’s turn, and then her aunt’s.

So there would never be any escape.

The morbid atavism was too powerful.

The roots of a family tree gnawed at by evil.

And yet she never would have thought her own daughters contaminated.

Nothing suggested it during their happy childhood.

They ran all over the place.

Jumped, danced, laughed.

It was unthinkable.

Charlotte, then Franziska.

Shut away in her room, the grandmother continues to mourn her dead.

The letter lying on her lap.

Soaked with tears, the words blur, distort.

What if Paula was right?

After all, that woman sings like an angel.

Yes, what she says is true.

Everyone around her dies.

So she must be careful.

Protect Charlotte.

She will see her less often, if it’s better that way.

Her granddaughter will no longer come to stay here.

That is the essential thing.

Charlotte must live.

But is that even possible?