Читать книгу The Man Who Folded Himself - David Gerrold - Страница 7

ОглавлениеThe Author Who Folded Me

Robert J. Sawyer

You ask most of today’s science-fiction writers what author first got them hooked on the genre, and they’ll say Asimov, Clarke, or Heinlein.

Not me.

For me, it was David Gerrold.

The very first adult science-fiction novel I ever read was, by coincidence, David’s very first solo novel, Space Skimmer.

It was the summer of 1972, when I was 12. My dad went to the local bookstore to buy me a couple of books to take to camp. He knew that I liked Star Trek reruns, and so he wanted to get me a science-fiction novel—even though he himself didn’t read SF. He asked a clerk for recommendations, and was handed Space Skimmer —solely because the author had written an episode of Star Trek.

I devoured that book, with its Escher spaceships and massive protagonist, and still think very fondly of it—after all, it hooked me on the genre for life.

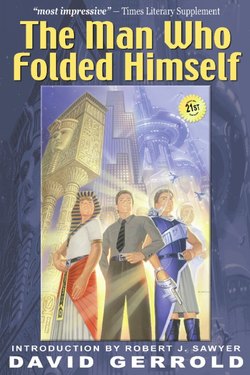

Two years later, I made my first trip to Bakka, Toronto’s then-new science-fiction specialty store, and there I found another Gerrold novel, freshly out in paperback after a successful run in hardcover. The cover painting—then and now—gave me the creeps: a young man’s face, eyes wide in horror, creased into neat squares as if it had been folded up, with tiny naked men hanging off the eyelids and lower lip, and cavorting in his hair.

The book, of course, was The Man Who Folded Himself—the same novel you’re holding in your hands right now. It was new then, and thanks to BenBella, it’s new again. The symbolism is almost too perfect: I feel as though I’m wearing Gerrold’s timebelt, handing that wonderful, wonderful book back to my younger self. What a delicious paradox it would have been to have seen a copy of this edition back when I was a teenager, with an introduction by me written thirty years later.

The Man Who Folded Himself makes you think like that: about timelines doubling back, about the future altering the past, about growing up to be who you were meant to be, about destiny.

Of course, I re-read the novel in order to write this introduction. I admire it even more now, as a middle-aged man, than I did as a teenaged boy; I found myself nodding over and over in understanding when elderly characters late in the book kept saying to younger ones, “You’re too young.”

Still, re-reading this book was also a bit disconcerting.

Why? Because David Gerrold’s fingerprints are all over me. I can see where my own style—short paragraphs, lots of em-dashes, pages of introspection with nothing external happening—came from. It’s David’s style. I owe him, and this tour de force, more than I ever realized.

David Gerrold was born in Chicago in 1944, but he grew up in Southern California. I first got to know him online, in 1990, on the CompuServe science-fiction literature forum, but we didn’t actually meet physically until five years later.

(Fan-boy confession: I know the exact moment, because, just like Daniel Eakins, the viewpoint character of The Man Who Folded Himself, I keep a journal. We met on Friday, August 25, 1995, at a Tor Books party at the World Science Fiction Convention in Glasgow, Scotland. And although I think I kept a cool outward demeanor, inside I was freaking out; I’d met lots of authors whose books I’d admired before, but this guy standing in front of me had written words that Captain Kirk and Mr. Spock had said!)

David’s Star Trek connection, by the way, goes much deeper than just the episode the bookstore clerk was alluding to when he handsold Space Skimmer to my dad, although there’s no doubt that David will always be best known to Trekkers for writing “The Trouble With Tribbles.”

But David also wrote two fascinating nonfiction books about the series, wrote by far the best episode of the animated Star Trek (called “Bem”), was an extra in Star Trek: The Motion Picture, and was instrumental in shaping Star Trek: The Next Generation (a version of Trek that conformed much more to David’s insightful analysis of what the show should be, as outlined in his 1973 The World of Star Trek, than to anything Gene Roddenberry ever articulated).

Reinventing Star Trek has occupied a lot of David’s career. There’s no doubt that his Star Wolf novels are his very successful attempt to do just that. But there’s also much more to him; indeed, what’s astonishing is just how versatile a writer he is.

For instance, David also wrote one of the great novels of artificial intelligence, called When HARLIE Was One (1972; a reissue is forthcoming from BenBella). He’s also the author of a wonderful action-adventure series—thirty years in the making, and still going strong—collectively known as The War Against the Chtorr.

And he was story editor for the first season of The Land of the Lost, the most intelligent Saturday-morning science-fiction show ever. It premiered in 1974, boasting scripts by Larry Niven, Ben Bova, Theodore Sturgeon, and, of course, David himself (David’s varied TV credits led to him teaching scriptwriting at Pepperdine University for many years).

Robert A. Heinlein’s juveniles were obviously an influence on David; his tribbles are clearly a loving homage to the Martian flatcats from The Rolling Stones. So it’s no surprise that he has written some superior juveniles of his own, most recently the trilogy Jumping off the Planet (2000), Bouncing off the Moon (2001), and Leaping to the Stars (2002).

David finally got his long-overdue Hugo and Nebula Awards, for his autobiographical 1994 novelette “The Martian Child” (a novel version was published in 2002). And I do mean long overdue: he started garnering Hugo and Nebula nominations with his very first works, but the actual prizes eluded him for decades. Indeed, The Man Who Folded Himself was nominated for both the Hugo (SF’s People’s Choice award) and the Nebula (the field’s Academy Award for Best Novel of 1973)—but it lost both awards to Arthur C. Clarke’s Rendezvous with Rama.

Now, Rama is a fine book, and it may have deserved the Hugo—but David should have got the Nebula. See, the Hugo is for the fan favorite of the year, and Rama, Clarke’s first novel since 2001: A Space Odyssey, certainly was that. But the Nebula is a peer award, given by writers to writers; it’s us tipping our hats to one of our own, acknowledging a work that pushed the envelope, that improved the field, that represented the best damned thing any of us had done in the past year.

Rendezvous with Rama was a lot of fun, but it was hardly groundbreaking (indeed, in its steadfast refusal to have any sort of characterization, it was a throwback to the hard SF of a quarter-century earlier). But The Man Who Folded Himself did change things. Not only was it the first truly original time-travel novel since H. G. Wells invented the subgenre back in 1895, but it’s also quite innovative in structure (go back when you’ve finished reading it and count the number of characters that appear in the book).

Moreover, The Man Who Folded Himself is rigorous in its extrapolation and absolutely unflinching in its characterization—the book is brutally frank about sex and narcissism, and deeply explores questions of sexual orientation. As it happens, David himself is gay, but his heterosexual love scenes—here, and in When HARLIE Was One and the Chtorr book A Season for Slaughter—are among the best in the genre. Just goes to show you what a good writer he is.

Re-reading this book, knowing all the things I know about David now that I didn’t when I first encountered it—that he’s a tireless fundraiser for the AIDS Project Los Angeles; that for all his counterculture Californian youth, he’s a fiercely proud American; that he’s a single dad to a wonderful (and now grown) adopted son—I see the pain and honesty and truth that he wrung out of his very soul and put into The Man Who Folded Himself.

You’ll see it, too. All you have to do is turn the page.

Robert J. Sawyer won the Nebula Award for Best Novel of 1995 (for The Terminal Experiment). His latest novel is Humans , the second volume of his “Neanderthal Parallax” trilogy from Tor. Visit his website at SFwriter.com.