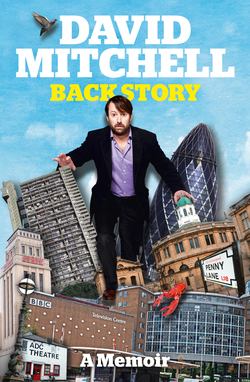

Читать книгу David Mitchell: Back Story - David Mitchell - Страница 14

Оглавление- 9 -

Beatings and Crisps

I was very happy at New College School. There were only about 130 boys, of whom 16 were choristers in the New College choir, and no girls – but when I started there, this wasn’t a down side. In fact, it was a plus. At the age of seven, I was extremely sexist.

It was ruled with charismatic and somehow witty strictness by the headmaster, Alan Butterworth, known by both boys and parents as ‘Butch’. This was not an ironic nickname for a man who was actually incredibly camp. He was incredibly butch – terrifying yet fun, like a ride at Alton Towers – a rotund bulldog of a man with a tremendous shouting voice.

But, for all his masculinity, he wasn’t unflamboyant: he drove an MG and wore immaculate pinstripe suits, brightly coloured socks and overpowering aftershave. This last could be a lifesaver, as it was often the only clue you’d get that he was lurking round the next corner with an outstretched fist. Don’t misunderstand me, he didn’t hit the boys. But you weren’t supposed to run in the corridors, so he would provide a fist for those disobeying that rule to scamper into. At the time I considered this policy very fair – and basically I still do. What I particularly liked about it was that Butch, having allowed you to smack your face against his hand, would not then rebuke you for running. The discovery of the crime, its punishment and forgiveness were simultaneous.

And, of course, when I say he didn’t hit the boys what I mean is that he occasionally hit the boys. I specifically remember his picking up Rawlinson-Winder by his hair for failing to grasp a point of Latin grammar. I hope you get a sense from that last fact not just that the man had a fiery temper but also that he was extremely comfortable with self-caricature.

He also administered the school’s official corporal punishment – known as ‘The Whacks’ – which, I was told (I was far too much of a conformist to be sentenced to it myself), involved being hit with a gym shoe made heftier by a kitchen weight wedged in the toe. The gym shoe’s name was Charlie. It is surely one of the world’s great sadnesses that billions of shoes go about their benevolent business in aid of mankind, day after day, protecting feet, providing warmth and support, unselfishly getting ducked in puddles and smeared with dog shit, and yet remain unnamed. Whereas this nasty little cunt of a shoe got lavished with affection like a pet.

Butch was as entertaining as he was intimidating and had a way of making you listen to him in school assemblies which I took for granted at the time but have realised in adult life is a gift possessed by few. His most memorable assembly, however, was entertaining in a way he wasn’t in control of.

He was obsessed with litter. It maddened him. He considered it, and I’m inclined to agree with him, as the thin end of some sort of anarchist wedge. He couldn’t understand why there was ever litter in the school playground when it was well supplied with both bins and teachers authorised to eviscerate you if you were caught dropping so much as the ‘tear here’ corner of some peanuts. So why, Butch furiously pondered, was there always a small amount of litter in evidence? Who were the anarchists among us – the apparently law-abiding middle-class nine-year-olds with a hidden desire to smash and smash and smash?

It’s a good question. I really don’t think any of us dropped litter – it was so easy not to. And yet there were always two or three bits of crap floating around the corners of the playground, usually empty crisp packets. This led to a new Butterworth theory: the crisp packets were blowing out of the bins, in a way that a Kit Kat wrapper, for example, would not. The boys were trying to obey the rules but were being beaten, not by him on this occasion, but by physics.

His solution was simple: when you put a crisp packet into a bin, it was vital that you scrunched it up first. Otherwise you were obeying only the letter and not the spirit of the anti-littering rule. I cannot over-emphasise how often the importance of scrunching was stated to us. (Certainly more often than we were told about autumn, another subject seriously over-covered by schools in my experience and of very little use in adult life. If I had stepped into the world as an 18-year-old unaware of the distinction between deciduous and evergreen trees and the hibernation or migration habits of various vertebrates, I think it would have taken a college friend about two minutes to get me up to speed – in the unlikely event that the ignorance ever became apparent. I mean, take the word ‘deciduous’ – I was taught it, I think, at the age of six, taught it again at the age of seven, ditto when eight and nine – and I’ve only used it twice since. And that’s in this paragraph, where it’s actually been very useful. Thanks, Miss Boon!)

But scrunching trumped even autumn. ‘Why oh why,’ Alan Butterworth would scream, ‘will you boys not learn the simple technique of scrunching up a crisp packet as you throw it away!? If you don’t get it soon, I shall have to ban crisps from the school premises,’ he threatened. He was saying this because the stray, apparently unscrunched packets were continuing to blow around in the small wind eddies in the playground’s corners, alongside the dead leaves of the more littering sort of tree; he was assuming, not unreasonably, that we were all too stupid to obey this simple instruction, that the dense, untrained, anarchic schoolboys were always too light-headed from their crisp-induced mid-morning carb and salt rush to remember about the scrunching after they’d poured the last delicious potatoey shards down their young throats. In his view, it was a level of idiocy unequalled in his long career of working with unformed brains.

So, one day, he decided to do a practical demonstration. He brought a crisp packet into assembly. It was quite incongruous to see it in his signet-ringed hand, like watching the Queen brandishing a ketchup bottle. The packet was empty – he never told us who had eaten the crisps. He held the packet aloft before vigorously scrunching it between both hands and placing the neat and unaerodynamic ball on the table in front of him. We then stood to sing a hymn.

If you’ve eaten crisps in the last few decades, you’ll know what happened next. During the hymn, the plastic packet gradually but determinedly unscrunched itself until it lay flat on the table. It stayed there for a few moments before drifting gently onto the floor. The problem with his scrunching instructions was humiliatingly laid bare – as was the towering arrogance of a man who had been banging on for years about this apparently simple solution to the littering problem without once trying it out himself. He was so sure of himself that the first time he ever attempted to scrunch up a crisp packet was in front of the whole school.

Now, there’s confidence for you. And foolishness. It’s like a metaphor for the First World War: the folly and the leadership rolled into one. He didn’t mention the flattened-out packet after the hymn. The official line was that the simplicity of the plan had been brilliantly demonstrated by the headmaster. But that’s not what the other teachers’ faces were saying.

He ran a terrific school, though – and it was terrific largely as a result of his labours. He’d been headmaster for over 25 years when I arrived, and his techniques clearly worked – the school’s academic reputation was excellent and, more importantly, it was an institution with high self-esteem.

That’s quite a trick to pull off for a small provincial prep school which was neither big enough nor rich enough to win at games. Somehow the boys at New College School were made to feel clever and significant. The staff seemed to have a swagger about them too which, when I think about it, was remarkable. It’s not a brilliant job, teaching in a small prep school. We do not, sadly, live in a society that values teaching very highly as a profession. We live in a society that pretends to, but gives the big money to footballers and bankers (and more to comedians and actors than they are probably worth, I’m very happy to admit, but personally I’m in it for the disproportionate praise).

But, even where teaching is valued as it should be, teachers from small independent prep schools are probably the least revered. Those little seats of learning have neither the sense of sacrifice of the state sector nor the glamour of the major public schools. But most of the staff at New College School seemed bright, interesting, fun, well-motivated and had been there years. Butch was clearly doing something right, even if it was mainly spotting clever and engaging people who weren’t very ambitious.

Whenever I think about the odd alchemy – the combination of planning, tradition, flexibility, inflexibility and luck – that it takes to make a functional institution, I think of New College School. And I worry that institutions like that are less likely to exist in Britain now. We don’t seem to live in a society where excellence in small but achievable aims is respected – where a man like Alan Butterworth, a very bright and charismatic Oxford graduate, would be willing to devote his entire career to making one small school as good as it could be.

Don’t get me wrong, I know being a prep school headmaster isn’t the same as founding an anti-malaria charity. But that’s sort of the point: it wasn’t saintly, neither was it glory-seeking. It was a modest, realistic goal. He didn’t want to run a bigger school or to make the school that he did run bigger. He just wanted consistency, and from that he derived contentment – or at least I hope he did. He certainly did some good, albeit only to the male children of fee-paying parents.