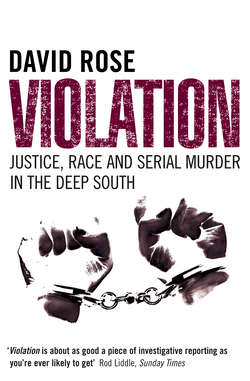

Читать книгу Violation: Justice, Race and Serial Murder in the Deep South - David Rose - Страница 6

ONE The Best Place on Earth

ОглавлениеWay down in Columbus, Georgia

Want to be back in Tennessee

Way down in Columbus Stockade

Friends have turned their backs on me.

Last night as I lay sleeping

I was dreaming you were in my arms

Then I found I was mistaken

I was peeping through the bars.

‘Columbus Stockade Blues’ (traditional)

‘We don’t take just anybody as a member,’ said Daniel Senne, the Big Eddy Club’s general manager. ‘They have to be known to the community. It’s not a question of money, but of standing, morality, personality. And they must be people who conduct themselves well in business. Integrity is important.’

We were talking in the hush of the club’s sumptuous lounge, perched on deep sofas, our feet on a Turkoman rug, surrounded by antiques. With the seasons on the turn from winter to spring, the huge stone fireplace was not in use, but there was no need yet for air-conditioning. From the oak-vaulted dining room next door came the muffled clink of staff laying tables for lunch: silver cutlery, three goblets at every setting, and crisply starched napery. The club’s broad windows provided a backdrop of uninterrupted calm. Framed by pines that filtered the sunlight, a pair of geese glided across the state line, making barely a ripple. Behind them, across a mile of open water, lay the smoky outline of the Alabama hills.

The minutes of the club’s founding meeting were framed on the wall, a single typed folio dated 17 May 1920. On that day, ten of the most prominent citizens of Columbus, Georgia, led by the textile baron Gunby Jordan II, had formed a committee ‘to perfect an organization for building a suitable club at a place to be determined … for having fish fries, ‘cues and picnics’. A postscript added: ‘Arrangements will be made at the club for entertaining ladies and children.’

The Big Eddy’s buildings had expanded since that time, but were still on the spot the founders chose, a promontory at the confluence of the Chattahoochee River and its tributary, Standing Boy Creek. In 1920, before the river was dammed, the turbulence formed where the currents came together was an excellent place to catch catfish. Anyone who ate Chattahoochee catfish now would likely suffer unpleasant consequences, thanks to the effluent swept downstream from Atlanta, but the club’s location remains idyllic. Escaping the traffic that mars so much of modern Columbus, I’d driven down a vertiginous hill to the riverside, where I followed a winding lane along the shoreline, past grand homes and jetties. Before passing through the club’s wrought-iron gates, I pulled off the road to feel the warmth of the sun. The only sounds were birds and a distant chainsaw.

Senne and his wife Elizabeth, dapper and petite, spoke with heavy French accents. They had served their apprenticeship in some of the world’s more glamorous restaurants: London’s Mirabelle and the Pavilion in New York, at a time when its regular patrons included Frank Sinatra, Bette Davis, Salvador Dalì, Cary Grant and the Kennedys.

‘If you had told me twenty years ago that this is the place to be, I would not have believed you,’ Elizabeth said. ‘But it is. They are nice people, really down-to-earth.’

Membership was strictly limited to 475 families, Elizabeth went on, and applicants must accept that their backgrounds would be carefully investigated by the board. Even in summer, the dress code was strictly observed: a jacket and tie for men, and for women, ‘no unkempt hair or wrinkled pants’.

The rules served their purpose, Daniel said. ‘It’s a good community. People take care of you.’ Just as in the 1920s, the club could count many of Columbus’s most distinguished inhabitants as members: the leaders of business, and local, state and national politicians. Former President Jimmy Carter was an honorary member for life.

In the week of my visit in March 2000, another of the city’s more venerable institutions, the Columbus Country Club, had announced the admission of its first two African-American members – both of them women who worked for the public relations departments of local corporations. I turned to Daniel and mentioned this news, then asked: ‘Do you have any black people yet in the Big Eddy Club?’

He shifted his posture awkwardly. ‘No. Not yet.’ He looked appealingly at his wife. ‘We don’t have black members, because none have applied.’

Later that day, as the light was starting to fade, I sat on the veranda of a Victorian house on Broadway, in the heart of Columbus’s downtown ‘Historic District’, with George and Vicky Williams, admiring their profligate springtime flowers. The area had once been in steep decline, but years of careful restoration had made it again a highly desirable neighbourhood. The Williamses were the first middle-class black family on their block, but Vicky said they’d encountered little overt prejudice. ‘Most of them just leave us alone.’

George, some twenty years older than his wife, was a highly decorated Vietnam veteran, and since leaving the military had built up several thriving businesses. Vicky had a university degree and worked at Columbus’s huge commercial bank, CB&T. She had lived in Columbus all her life: attended its schools; socialised widely; watched its local TV news and read its newspaper, the Columbus Ledger-Enquirer. How important did she think the Big Eddy Club was in the way the city was run?

Vicky looked at me blankly. ‘What’s the Big Eddy Club?’

Columbus, population a little less than 200,000, is Georgia’s second city, 110 miles south of the state’s capital, Atlanta. Running across it is a racial fissure, a rift with an exact geographical position, its line marked by the east – west thoroughfare known for most of its length as Macon Road. With exceptions unusual enough to be noticeable, white people – about 65 per cent of the total – live to the north, and black to the south. No longer legally segregated, they will mingle at work and use the same stores and restaurants, but in general they do not mix in their social lives, or at home. This de facto segregation still divides other American cities, on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line. But in places like Columbus it tends to be more noticeable. One of its lesser implications is the fact that a well-educated, middle-class black family has never even heard of the fine dining club where their white counterparts take their families for Sunday brunch, marry off their daughters and hold their charity balls; a place where rich and powerful people relax in each other’s company. Unbeknown to George and Vicky Williams, their near neighbours included at least one Big Eddy member, a prominent lawyer.

Columbus stands amid the rolling granite landscape of what, before the boll weevil infestation of the early twentieth century, used to be Georgia’s cotton belt. In summer, the sun irradiates the city with a lacquered intensity for months on end, bringing with it a plague of bugs. Winters are pleasantly mild, although a shift in the wind can bring plummeting temperatures and even, occasionally, tornadoes. The city takes up far more room than its inhabitants need. Its low density has allowed them to cultivate generous, handsome gardens, and there are so many trees that viewed from above, from atop one of the hills on the eastern perimeter, it barely looks like a city at all, but an expanse of forest. At ground level, the foliage turns out to hide a sprawling hinterland of strip malls and snarling expressways, built to connect mazes of suburban subdivisions which on superficial inspection could be almost anywhere in America. Beyond the Victorian downtown enclave, anyone crossing a road on foot takes their life in their hands.

To the west, across the Chattahoochee, is Alabama, here represented by Phenix City, long a centre for gambling and illicit alcohol. In the 1950s the gangs of Phenix City took to murdering elected officials who were trying to clean it up, and it remains the only town in the United States where martial law has had to be imposed in peacetime. Some of those gangsters’ descendants now occupy positions of the greatest respectability in both Georgia and Alabama.

For many Americans, Columbus has a fame and importance out of proportion to its size. It was in his Columbus drugstore during the 1870s that the chemist John Stith Pemberton first mixed the ingredients for his patent soda drink, Coca-Cola. (That original formula is said to have included a stimulating ingredient which is missing from its later versions – cocaine.) To the immediate south of the city lies Fort Benning, the world’s largest infantry base, a place familiar to millions who have served in the military. Its short-haired inhabitants can often be seen in Columbus on weekends, in the dive bars and strip lounges on Victory Drive, a venue for occasional drunken shootings, and with their girlfriends at the motels clustered round the exit ramps on the road to Atlanta, Interstate 185. On my very first night in Columbus, I found myself in the Macon Road Days Inn, where some recent recruits had decided to hold a party in the room above mine. At 3 a.m. it sounded as if they were rounding off their celebrations by repeatedly throwing a heavy refrigerator against the walls and onto the floor. A few hours later, as I blearily went in search of breakfast, there were two used condoms, pale translucent jellyfish, on the concrete stairs.

In Oxford, my English home city, which has a population about two-thirds of Columbus’s, the Yellow Pages phone book entries under the heading ‘Places of Worship’ take up less than a page. In Columbus, they require fourteen, listed under a rich array of denominations: from ‘Churches, African Methodist Episcopalian’ to ‘Churches, Word of Faith’. There are five separate headings to cover the different varieties of Baptist, and seven for Methodists. In Columbus can be found many kinds of Reverend. At the fancy places, such as the imposing neoclassical First Baptist Church of Columbus on Twelfth Street, they are solemn men in silken robes. At the other end of the market is Eddie Florence, a former cop who turned to religion after a short spell in the penitentiary. Dominating his church, deep in South Columbus, on the day of my visit was a drum-kit and electric organ; the premises doubled from Monday to Friday as the office for Florence’s real estate and loans business. A plump, intense, beaming figure, he told me: ‘I don’t suppose you’ve had much opportunity to take out a mortgage from a man of God before?’

For many of Columbus’s citizens, whose behaviour, I learnt, was not always conventionally devout, Church and community are one and the same. If one only knew a person’s choice of place of worship, one would be able to assume much about his or her race, class and social standing. But Columbusites’ faith is no veneer. They give generously to charity, and their routine enquiries after one another’s health appear to express a genuine concern. As I rapidly discovered, their habit is to welcome strangers, even those armed with a notebook and difficult questions.

Its citizens may be oriented towards the world to come, but Columbus, according to Mayor Bob Poydasheff, with ‘its wonderful people and great climate, is simply one of the best places on earth – cosmopolitan but always neighbourly’. The city, states his website, is ‘in a period of unprecedented building and development, which is bringing our quality of life to new highs’. He enumerates its blessings: ‘[The] Chattahoochee Riverwalk, River-Center for the Performing Arts, Springer Opera House, Coca-Cola Space Science Center, Columbus Civic Center, our South Commons Softball Complex including a world-class softball stadium and much, much more.’

The economy, Mayor Poydasheff adds, is buoyant. For more than a century, Columbus has been quietly dominated by a small number of wealthy families. Gunby Jordan, who founded the Big Eddy Club, came from one of them. In 1919, two of these dynasts, Ernest Woodruff and William C. Bradley, bought the Coca-Cola corporation for $25 million. (In Bradley’s case, some of this money was originally derived from his father’s former slave plantation across the river in Alabama.) Their investment was to multiply several thousand times, and spread among their descendants, it has fructified Columbus. Bradley also founded the CB&T banking conglomerate. Its offshoot, the financial computing firm TYSYS, has been quartered since 2002 in a line of large, reflective buildings just north of the former textile district, and is the world’s largest processor of credit cards.

It is only in the south of the city, on the other side of its racial frontier, that the signs of twenty-first-century prosperity are less visible. There, the surfaces of the roads are potholed and pitted. There are junkyards piled with ancient cars, and meagre stores with signs done in paint, not neon. In the poorer districts, lines of low-rise public housing projects stand amid meadows of ragged grass, competing for space with wooden three-room ‘shotgun’ houses, whose squalor would not look out of place in Gaza or Soweto.

The clubs of south Columbus are different, too. The biggest, a huge, low-ceilinged cavern just off Victory Drive, belongs to the R&B singer Jo-Jo Benson, responsible for a string of hits in the sixties and early seventies, including a national pop chart number one, ‘Lover’s Holiday’. A big, bearded bear of a man, the day we met he was dressed in a vivid striped caftan. He showed me round the club and took me into his office, taking pains to check that the large-calibre revolver he kept in the drawer of his desk was still there. ‘This town is a trip,’ he said. ‘A lot of people don’t want to see you make no money or succeed. Coming here from Atlanta is like leaving earth and going to the twilight zone, or travelling back in time.

‘But this is the biggest, the nicest club in town, and I’m a public figure. A lot of people ask me why I stay. Well, I was raised in Phenix City, and more than that, I don’t want to go in for that big-city stuff – gangs and shit. At the end of the day, Columbus is a place to sleep, lay down and rest. Most of the time I don’t get no trouble.’

Benson led me out of the club into the parking lot, and asked me to sit in the passenger seat of his impressive grey sports utility vehicle. ‘I’ve got sound equipment worth thousands of dollars in here,’ he said. He opened the glovebox and removed an unmarked CD. ‘We recorded this last week. Ain’t finished with it yet.’ It turned out to be a romantic duet of heartbreaking sweetness and purity with another local singer, Ruby Miles. Jo-Jo’s music filled the car and brought to mind decades of Georgia gospel, blues and soul: Otis Redding, Randy Crawford, Sam Cook. For a moment he looked bashful. ‘You like it? Tell your friends.’

I made my first visit to Columbus to investigate what looked like a paradox. It was 1996, and the British newspaper that employed me, the Observer, had asked me to go to Georgia to write about the death penalty. My editors were intrigued by the fact that the state’s death row held two prisoners who had exhausted every possible appeal, but whose execution had been indefinitely delayed. The reason, it seemed, was that Georgia wanted to wait until after the Olympic Games, which were shortly to be held in Atlanta. In Britain, as in the rest of Europe, capital punishment had been abolished many years earlier, and the paper wanted me to try to find out why parts of America still found it so attractive.

I began by talking to defence attorneys in Atlanta. They all said the same thing: I should go to Columbus. While its overall crime rate was relatively low, since 1976, when a case from Georgia persuaded the US Supreme Court to reinstate the death penalty, Columbus had sentenced more men to die than anywhere else in the state. By the middle of 1996, four had been executed, all of them African-American, and eight were still on death row. At least another twelve had been condemned by Columbus judges and juries, but had won reprieves in appeals. If one worked out the number of death sentences per head of population, Columbus was one of the most dangerous places to commit a murder in the whole of the United States.

A few days later I found myself in Columbus’s second tallest building, a harsh monstrosity in white concrete which would not have looked out of place in Stalinist East Berlin, the eleven-floor Consolidated Government Center. In front of a view across the river sat Judge Doug Pullen of the Chattahoochee Circuit Superior Court, which covers the city and five neighbouring counties. It had been a hot and languorous weekend, and I knew Pullen’s reputation: criticised for his record a few years earlier by Time magazine, he had told the local media that Time’s problem was that it had yet to discover glasnost, the new policy of openness pioneered by the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, and was still a ‘lovely pink colour’. Nevertheless, his lusty enthusiasm for capital punishment took me by surprise.

‘I would guess that your experience of seeing bodies splattered and mutilated is limited,’ he said by way of introduction. ‘Unfortunately, mine is not.’ A spreading, heavy-set man with round eyes too small for his face, he moved a little stiffly. ‘In all honesty, abolishing the death penalty would have a negligible effect on crime. But the effect on the American people would be horrific. It would be symbolic, like flag-burning.

‘We like to talk tough on crime, but we’re soft. And every time you get an execution, you get people picketing, saying it’s so cruel. Phooey. The first man I prosecuted for capital murder, even if he’d been executed on his due date, it would have been nine years to the day after he committed the crime. And then he got a stay, and all the anti-death penalty people went out dancing. In my view, there should be one appeal, and one only, then that’s that: homeboy goes.’

‘What about life without parole?’ I asked.

Pullen shook his head. ‘It’s a weak sister, my friend. A horribly weak sister.’

As we talked, a big, stooped man with unusually bright blue eyes entered the room without knocking. The two of them stood, whooped, and made high fives. ‘Meet Gray Conger, my successor as District Attorney,’ Pullen said.

‘We still on for that barbecue this weekend?’ Conger asked him. Pullen replied in the affirmative. Before Pullen became a judge, the two men had worked together as prosecutors for more than twenty years: Pullen had been DA, and Conger his assistant. That was the way things had been done for decades in Columbus, they explained: an orderly progression from District Attorney to Superior Court judge meant that four of the five judges then sitting had spent most of their careers in the prosecution office.

‘They’re friends of mine, and they employed me,’ Conger said. ‘But don’t get the idea that that means I get any advantages in court. All it does is give us a smooth transition when a new DA comes in.’

‘Why do you think the city has sent so many men to death row?’ I asked.

‘I just don’t know,’ Conger shrugged. ‘Maybe it’s just that we’ve had some awful horrible murders around here.’

One thing he was sure of. ‘In deciding which cases to seek the death penalty, and in the way we work in general, race is not a factor. In the South in my time, over the last thirty years, there’s been the most amazing transformation. Southerners are very conscious of race. They go out of their way not to be accused of racial bias.’

Later that afternoon, Pullen took me in his battered Volvo down to Fort Benning, where he taught a class in criminal law and capital punishment to soldiers and police patrolmen. I still had no real idea why he was wedded so strongly to capital punishment, but there was obviously nothing confected about the strength of his feeling. ‘I love people,’ he remarked happily as we sped through the gates of the vast military base. ‘You can probably tell that. So if you hurt one of my people, I’m going to come after you.’

In the past, he said, he had received dozens of letters asking him to reconsider death sentences. ‘The strange thing was, they all seemed to come from Holland and Wales. Don’t think I can’t recognise an organised letter-writing campaign when I see it. I got news for you. My education puts me in the top 3 per cent in this country, but I couldn’t name a single city in Wales. Folks round here don’t necessarily care what folks in Wales think of them. I guess those letters came from Amnesty International or something. They should be concentrating on real human rights abuses, like in the Third World.’

Pullen’s class, in an echoing room easily big enough to contain his hundred students, was a bravura performance. ‘Let me give you a little insider tip,’ he began. ‘Our fine Attorney General, Michael Bowers, is planning to run for Governor.’

‘How do you know?’ someone asked.

‘Bowers made his intentions plain to me personally. When we met up recently’. Pullen paused, then winked: ‘At an execution.’

An Alabama state trooper, so fat he seemed almost triangular, asked how lawyers got to be judges. Pullen chuckled. ‘You may rest assured that anyone successful in defence litigation need not apply. At least not on the Chattahoochee circuit.’

After the seminar, Pullen took me to dinner in a barbecue restaurant downtown. As we consumed a small pork mountain, I asked him about one of the cases that had attracted those letters from Holland and Wales, a capital murder he’d prosecuted in 1976. The defendant had been a mentally retarded man named Jerome Bowden, an African-American aged twenty-four. The body of his victim, Kay Stryker, a white woman of fifty-five, was found in her house, knifed and beaten, several days after her death. Afterwards, the police searched the home of her sixteen-year-old neighbour, Jamie Graves, and found an old pellet gun, its butt stained with her blood, together with her jewellery. Graves admitted burgling her home, but claimed she was killed by his friend Bowden. In return for his help, he was sentenced to life rather than being given the death penalty.

Bowden soon heard the police were looking for him. He walked up to a squad car he saw in the street, and asked if he could be of help. He was arrested on the spot, and less than two months after the murder, he stood trial. Pullen’s case rested on Bowden’s confession. He tried to retract it on the witness stand, saying he hadn’t been in Stryker’s house at all, and that a police detective had promised ‘to speak to the judge’ to save him from the electric chair in return for his signature. At the start of the hearing, Pullen had exercised his right to strike prospective jurors, so removing all eight African-Americans from the panel and ensuring that Bowden was tried only by whites. They did not believe him, and found him guilty on the second day of the trial.

In Georgia, as in many American states, capital trials consist of two phases. The first is the ‘guilt phase’, when the jurors have to decide guilt or innocence; in the event of a guilty verdict, they will go on to the ‘sentencing phase’, when it becomes their responsibility to decide whether a murderer should live or die. Here Bowden’s attorney, Samuel Oates, begged the jury not to impose the death penalty, arguing that his client was of low intelligence and had a ‘weak mind’.

Pullen dismissed this suggestion, arguing that it had been cooked up ‘so someone can jump up and say, “Poor old Jerome, once about ten years ago his momma told somebody he ought to see a psychiatrist.” He is not a dumb man, not an unlearned man … He certainly knows right from wrong.’ In his view, Bowden was ‘a defendant beyond rehabilitation’, for whom death was the only possible sentence, because he had been sent to prison – for burglary – before. He held up a photograph of Stryker’s body. ‘How do you take a three-time loser who would take a blunt instrument and beat a harmless fifty-five-year-old woman’s head into that? You can look through the holes and see the brains.’

In the nineteenth century, slavery’s apologists had justified human bondage by equating black people with animals. Appealing to the jury to decree the death of a mentally retarded teenager, Pullen invoked this tradition: ‘This defendant has shown himself by his actions to be no better than a wild beast – life imprisonment is not enough. Why? Because he has killed. Because he has tasted blood.’ It would take courage for the jury to vote to have Bowden put to death, Pullen averred; much more courage than giving him a life sentence. But ‘it took more courage to build this great nation, and it will take more courage to preserve it, from this man and his like’.

Almost ten years later, in June 1986, Bowden had lost his every appeal, and his last chance lay with Georgia’s Board of Pardons and Parole. However, evidence had now emerged that Pullen had overstated Bowden’s mental capabilities. In fact he had an IQ of fifty-nine, and was well within the clinical parameters of mental retardation.

Bowden’s pending execution became a cause célèbre. The international music stars Joan Baez, Peter Gabriel, Lou Reed and Bryan Adams signed a petition to stop the killing, and sang at a protest concert in Atlanta. A flurry of last-minute legal petitions bought a few days’ stay of execution, but on 23 June the Pardons and Parole board decided that he had indeed, in Pullen’s phrase, ‘known the difference from right and wrong’ at the time of Kay Stryker’s murder. The following morning, Bowden was led into the death chamber, his head and right leg shaved. The prison warden held out a microphone to carry his last words to an audience of lawyers, reporters and officials.

‘I am Jerome Bowden and I would like to say my execution is about to be carried out,’ he said. ‘I would like to thank the people of this institution. I hope that by my execution being carried out it will bring some light to this thing that is wrong.’ His meaning was ambiguous, but most observers thought he was referring to his own electrocution. Then he sat down in the electric chair. There was a short delay when the strap attaching a leather blind to hide his face from the audience snapped, and had to be replaced. But when the executioner threw the switch, the chair functioned smoothly. Eighteen months after Bowden’s death, the Georgia legislature passed a new statute barring state juries from sentencing the mentally retarded to death.

Pullen told me he still slept easy over Bowden’s execution. ‘I never heard Jerome Bowden was retarded until Joan Baez had a concert in Atlanta and said he was retarded. Jerome Bowden was no rocket scientist, but he knew words like “investigation” and “detective” and was kind of articulate. On death row, they said he was a deep thinker in Bible class. He was fit to execute.’

When we left the restaurant, it was already late. The cicadas were out in force, their strange chorus loud enough to overcome the noise of the distant traffic. We strolled back towards Pullen’s car, the shadows of the historic district’s houses shifting under a blurry moon. Not far from the Government Center, Pullen stopped.

‘This is the site of the old courthouse. This is where they seized a little black boy and took him up to Wynnton, right by where the library is now. He wasn’t more than twelve or thirteen and they shot him thirty times. The son of the man who led that mob grew up to become a judge. Kind of interesting, isn’t it?’

I left town next day intrigued but also bewildered, and with no real answers as to why Doug Pullen and his colleagues had such a passion for putting men to death. But notwithstanding Gray Conger’s protestations, I was beginning to suspect that if there was a place where the ‘amazing transformation’ in race relations that he claimed to have witnessed had been least effective, it was within the criminal justice system.

In police stations, prosecutors’ offices and the criminal courts, societies attempt to deal objectively with their most traumatic events. But the horrifying nature of those events sometimes makes objectivity impossible to achieve, and creates opportunities for ancient hatreds and primeval fears to reassert themselves. Stories about crimes and criminal trials, writes the British historian Victor Gatrell, permit ‘a quest for hidden truths, when obscure people have to articulate motives, interests, and buried values and assumptions … They expose fractured moments when people were in exceptional crisis, or observers were moved to exceptional passion.’ They may say more about the way societies function than any number of broader surveys.

Before I left Georgia on that first visit I drove out to DeKalb County, at the foot of Stone Mountain, the great, bald dome of granite where giant sculptures of Confederate leaders have been carved into the rock face. I was there to see Gary Parker, an African-American attorney and former state Senator who’d spent most of his career doing criminal defence work in Columbus. Parker, a tall, slim man of forty-six whose hazel eyes seemed to brim with energy, had fought some famous legal battles, both civil and criminal, against tough odds. ‘In Columbus,’ he said, ‘usually there’s only two blacks in the courtroom. Me and the defendant.’

We talked about the city and his work there long into the evening. I was about to leave when he took a pull on his menthol cigarette and paused, as if debating whether to say what was on his mind. Outside the windows of his spacious, homely den, thickets of trees cast dusky shadows. Recently, he told me, he had left Columbus for good, unable to bear an atmosphere that he had begun to find intolerably oppressive.

‘Sometimes I think something really bad happened in Columbus,’ he said quietly. ‘That there’s some terrible secret from the past. Like a massacre or something. I keep on expecting someone to go digging foundations at a construction site and find a mass grave. Raised as I was in the South, images of lynching come to mind all the time, and there have been times when I’ve sat in court there and felt as if I was witnessing a lynching in my lifetime. I don’t know what it was, but something happened there. It’s like a curse.’

I got up to go. I knew I had come nowhere near to understanding Columbus’s paradoxes and mysteries. I suspected that their solutions must lie deep in the city’s history, and in the way it had been remembered and set down, and had thus helped form contemporary outlooks and mentalities. I also knew I’d be back.

Most of the remains of antebellum Columbus are to be found in Wynnton, the neighbourhood Doug Pullen had mentioned at the end of our evening. It was once known as the ‘millionaires’ colony’, and its placid exclusivity dates back to the time when Columbus was first laid out in 1828, and its richer citizens began to construct their homes there, on the slopes of Wynn’s Hill, a safe distance from the downtown stews and factories springing up by the side of the Chattahoochee. They were joined by cotton planters from the surrounding countryside, who saw in Wynnton the ideal location for an urban retreat. Their Palladian temples and mansions decked with Louisiana-style wrought-iron tracery were once at the heart of a social whirl that is said to have rivalled more famous centres of Old South, slave-holding glamour, such as Charleston, Richmond and New Orleans. There were lavish picnics, barbecues, marching bands and orchestras, full-dress hunts and glittering balls.

As late as the 1970s, Wynnton remained a kind of Arcadia, writes the Columbus journalist and author William Winn. His nostalgic description carries more than a whiff of Gone with the Wind: ‘Nearly every house, however modest, has a lawn, and every spring Wynnton is ablaze with pink and white azaleas, the neighbourhood’s particular glory.’ Later, the district was to become synonymous not with colourful flowers, but with rape and murder. But until then ‘it had always been a calm, peaceful neighbourhood, almost entirely free of crime except for an occasional cat burglar. Generations of black nurses rolled perambulators containing generations of white children down the shady sidewalks, and every June the air became so redolent with the fragrance of magnolias and fading gardenias it almost made one dizzy.’

The economic strength of Columbus has long enabled it to wield disproportionate political influence in Georgia, and the torrid months that preceded the South’s secession from the United States were no exception. By 1859, just thirty-one years after the time when it lay on the ragged American frontier, the city is said to have contained eleven churches, four cotton factories, fourteen bars, forty-five grocery stores, four hotels, thirty-two lawyers, three daily newspapers and a magnetic telegraph office. Cotton spun in Columbus could be taken by paddle steamer down the Chattahoochee all the way to Apalachicola on the Florida Gulf Coast, a distance by river of almost five hundred miles. In May 1853, the closing of a last ten-mile gap saw the completion of the Muscogee-Southwestern railroad. ‘It was then that a great railroad jubilee was held in Columbus,’ writes the local historian Etta Blanchard Worsley. ‘Mayor J.L. Morton mingled water from the Atlantic Ocean with the waters of the Chattahoochee, typifying the union of Savannah and Columbus.’ In the whole of what was about to become the Confederate States of America, the industrial production of Columbus was second only to that of Richmond, Virginia.

In the 1860 census, the population of Muscogee County (including Columbus, its suburbs such as Wynnton and the surrounding rural districts) was made up of 9,143 whites, 165 free blacks and 7,921 slaves. It was on this human property that the city’s wealth depended, as its civic leaders recognised. As the abolitionist movement gathered strength in the North and Midwest, the lawyer Raphael J. Moses argued as early as 1849 in favour of leaving the Union in order to protect the right to own slaves. Five years later, America’s first secessionist journal, the Corner Stone, began publication in Columbus. Another early supporter of secession was the local attorney Henry Lewis Benning, later to become the Confederate General whose name is still borne by the military fort. In 1859 he warned that if Lincoln were elected President, all who resisted the end of slavery would be summarily hanged by the ‘Black Republican Party’. Immediate secession was the only way to escape the ‘horrors’ of abolition. ‘Why hesitate?’ Benning asked. ‘The question is between life and death.’

As the political temperature rose, individuals suspected of abolitionist sympathies faced violent retribution. In December 1859, William Scott, the representative of a New York textile company, was run out of Columbus by a vigilante committee, which claimed he displayed ‘more interest in the nigger question than in the real object of his visit’. Like the French aristocracy before the Revolution, Georgia’s whites had been seized by a grande peur. Their terror of a slave insurrection was fuelled by the distant memory of Nat Turner’s bloody revolt in Virginia in 1831, and the recent raid by the Christian radical John Brown on the federal armoury at Harpers Ferry in the same state, planned as a means of arming a putative slave rebellion. In the wake of the raid, which had been crushed by the future Confederate general Robert E. Lee, the 1859–60 session of the Georgia Assembly enacted harsh new measures against free blacks, who were seen as potential focuses for discord. Blacks from outside the state were forbidden to enter it on pain of being sold into slavery, and any current free black resident found ‘wandering or strolling about, or leading an immoral, profligate course of life’ could be charged with vagrancy and also sold. It was thenceforth forbidden for a master to free his slaves posthumously in his will, making slavery in Georgia somewhat less escapable than in ancient Rome.

From this febrile milieu sprang the Columbusite US Senator Alfred Iverson. ‘Slavery, it must and shall be preserved,’ he proclaimed in a speech in 1859, going on to argue that the only way to achieve this end was to form an independent confederacy. By the end of 1860, after Lincoln’s victory in the presidential election, the second Georgia Senator, Robert Toombs, who owned a plantation south of Columbus and later became the Confederacy’s Secretary of State, had also backed secession. On 23 December, the night South Carolina became the first state to leave the Union, Columbus celebrated with a torchlight procession, bonfires and fireworks. The city had already spawned several companies of a paramilitary ‘Southern Guard’, which joined the march in their freshly designed uniforms, rifles at their shoulders. J. Harris Chappell, aged eleven, a future President of Georgia College, wrote to his mother: ‘I think nearly all the people of Columbus is for secession as they are wearing the cockade. There are several small military companies one of which I belong to … the uniform is red coats and black pants. Lenard [sic] Jones is captain. I’m a private. Tommy’s first lieutenant. Sammy Fogle has got the measles.’

Georgia’s Ordinance of Secession passed the State Constitutional Convention on 21 January 1861, to be greeted in Columbus with a mass meeting of citizens, another torchlight procession, and the firing of cannon salutes. The common people shared the zeal of the small, slave-owning elite. The State Governor, Joe Brown, was warning them that if Lincoln were to free the slaves, blacks would compete for jobs with poor whites, ‘associate with them and their children as equals, be allowed to testify in court against them, sit on juries with them, march to the ballot box by their sides … and ask the hands of their children in marriage’. (Georgia’s laws against miscegenation were not struck down by the US Supreme Court until 1967.) In the first months of the war that began that April, Columbus sent eighteen companies to the front – 1,200 men, more than a fifth of its pre-war white population.

The war both blasted and, at least for a time, enriched Columbus. One family, that of the pioneering entrepreneur Colonel John Banks, whose seventh- and eighth-generation descendants were still occupying the magnificent Wynnton mansion known as The Cedars in 2006, lost three sons. As they fought what increasing numbers came to perceive as a ‘rich man’s war’, ordinary Confederate soldiers not only died in combat, but fell prey in vast numbers to malnourishment, cold and disease. N.L. Atkinson, who lived on the Alabama side of the Chattahoochee, wrote in a letter to his wife, ‘this inhuman war is putting our whole country in mourning’. But while its youth fought and fell at Gettysburg, Antietam and Manassas, Columbus’s industry boomed. By 1862, the Eagle textile mill was running non-stop, and producing two thousand yards of worsted for uniforms each day, as well as cotton cloth for tents, thread, rope and rubberised fabric. The city’s ironworks rapidly expanded, to become the Confederacy’s second-largest source of swords, pistols, bayonets, artillery pieces, steam engines, boilers and ammunition. The newly established Confederate Navy Yard made a gunboat 250 feet in length.

Of the industrial quarter that was the scene of this feverish activity, not a trace remains. As the war reached its closing stages, the Union’s Major General James Harrison Wilson was ordered to sap the Confederacy’s resistance by striking at its last centres of manufacturing. Having dealt with the cities of Selma and Montgomery in Alabama, his force of thirteen thousand reached the west bank of the Chattahoochee on 16 April 1865 – a week after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. Neither Wilson nor the ragtag of militia units defending Columbus had received this news; they were likewise unaware that Lincoln had been murdered on 14 April. After a short battle on the Alabama shore, the Yankees swarmed across the Fourteenth Street bridge and took the city that Wilson had called ‘the door to Georgia’ in just over an hour. Next day, Wilson ordered that ‘everything within reach that could be made useful for the continuance of the rebellion’ must be destroyed. Mills, foundries, warehouses and military stockpiles were put to the torch, together with three gunboats, which drifted for miles down the river in flames. While the Union army went about its work, civilian mobs looted stores and small businesses. Even respectable, well-dressed women were said by one witness to have participated: ‘They frantically join and jostle in the chaos, and seem crazy for plunder.’ As Wilson moved on towards Macon on 18 April, leaving only a small garrison, Columbus was ‘a mass of flame and coals’.

For many years, Columbus’s business and political elites have gently looked down on their counterparts in the parvenu state capital to the north, Atlanta, which was still a featureless rural tract when Columbus was building its grid of downtown streets. Perhaps their superior attitude stems in part from their ancestors’ differing response to Yankee-inflicted devastation. While Atlanta complained about its treatment at the hands of General William Tecumseh Sherman during his notorious march to the sea, Columbus got on with building new factories. Most of the imposing red-brick buildings downtown date from the late 1860s and seventies. One of them is built on the site of its predecessor, the Eagle mill. Above its mullioned arches, a banner in brickwork picks out the legend ‘Eagle and Phenix’. Within a month of Wilson’s fire, the iron foundries were open again for business. Louis Halman, formerly the proprietor of a sword works, retooled his charred and shattered premises and began, symbolically enough, to manufacture ploughs.

Impressive as this physical rebuilding was, in the period after the South’s defeat, Columbus also engaged in a process of psychic reconstruction. In common with other communities whose long-term material suffering was much more severe, an important part of the city’s attempt to come to terms with its role in America’s bloodiest war was its adoption of a narrative myth – the legend of the Lost Cause. On the one hand, this was a way of making the past seem acceptable. At the same time, it contained the ideological seeds for the region’s defining social characteristic far into the twentieth century – white supremacy.

There is a line in William Faulkner’s play Requiem for a Nun which has become a cliché in writing about the South: ‘The past is never dead. It’s not even past.’ Faulkner meant it to apply to the enduring consequences of an individual’s actions, not the influence of history – and in any case, the past affects the present in regions other than the states of the former Confederacy. But ultimately the past doesn’t die because it is remembered, and memory, as historians have recently begun to understand, is a potent influence on contemporary events, an analysis that seems especially true of the American Civil War. ‘Americans have needed deflections from the deeper meanings of the Civil War. It haunts us still; we feel it, but often do not face it,’ writes the Amherst professor David Blight. Instead of a titanic struggle over principle, America preferred to remember the war through ‘pathos and the endearing mutuality of sacrifice among soldiers’, so that ‘romance triumphed over reality’. The consequence, Blight concludes, has been ‘the denigration of black dignity and the attempted erasure of emancipation from the national narrative’.

In the Lost Cause account of the Civil War, partially created and vividly expressed in Columbus, slavery, racial oppression and the struggle against them have all but disappeared. The Confederate soldiers’ courage and independence were to be celebrated, but not the realities of the ‘peculiar institution’ – slavery – they had happened to be defending. If slavery were to be mentioned at all, it was to be as something decent and necessary, grounded in mutual respect.

Histories of Columbus by authors from the city are steeped in the different aspects of this myth. For Nancy Telfair, a local journalist whose History of Columbus, Georgia was published in 1928 and recently reissued, the only principles involved in secession and the war were ‘states’ rights’ to determine whether or not to permit slavery, and the prerogative of owners ‘to assert their rights to equality and the protection of their property’. It simply did not occur to her that the fact that this property happened to consist of human beings made it different from bales of cotton or farmland. According to Telfair (her real name was Louise Jones DuBose), slavery was merely ‘a characteristically Southern industry’ destroyed by the war.

Etta Blanchard Worsley’s Columbus on the Chattahoochee was published in 1951, at an early stage of the modern civil rights era, when Georgia’s African-Americans were fighting in court for the right to vote and other basic liberties. Like Telfair’s, her book was published by the Columbus Supply Company, and taught in the city’s schools. Both works can still be found on the shelves of Columbus’s libraries. The Reverend Joseph Wilson, father of the US President Woodrow Wilson, had argued that bondage was an ‘ameliorative’ institution, which could improve the spiritual welfare of slaveholders and slaves alike. Echoing his logic, Worsley characterises slavery as ‘part of the evolutionary process of the civilisation of the African tribes’. There might, she adds, have been isolated examples of abuse by ‘low-class overseers’. In general, however, ‘there had been the kindliest feelings between the whites and the Negroes … the tie that bound the slave to the master with whom he was closely associated was one less of law than of mutual need, confidence and respect’. As for abolition, it was but a ‘fanatical demand’ orchestrated mainly by Northern Quakers, peddled by means of ‘inflaming editorials’, and ‘little did it help for the South to plead for conciliation. The agitation went on for forty years.’

If Worsley is indignant about the end of slavery, Sterling Price Gilbert, long a member of Georgia’s Supreme Court and arguably the most distinguished jurist Columbus has produced, is both egocentric and mawkishly sentimental. In his 1946 memoir A Georgia Lawyer, he writes of the liberation of his own family’s property:

The earliest recollection that I have of my home takes me back to the age of about three … Our cook and her son, Anderson, who was the yard boy and who had ‘looked after’ me were leaving. I had a strong attachment, almost love, for Anderson. He had been my bodyguard and my playmate. My heart was filled with sorrow, and I cried because he was leaving me. I went to the road with him and his mother. I can remember standing with feet apart, in the middle of the road, with tears streaming down my face, waving goodbye to my two friends. Every hundred yards or so, they would turn round and wave.

Justice Gilbert does not ask why his father’s chattels, given a choice for the first time in their lives, had elected to leave.

Telfair, Worsley and Gilbert were all writing in the twentieth century, but the Lost Cause legend had emerged much earlier, and Columbus played a direct and significant role in its formation. On 12 March 1866, less than a year after Wilson’s raiders torched the city’s factories, Miss Lizzie Rutherford, her cousin Mrs Chas. J. Williams and their friends in the Soldier’s Aid Society of Columbus began what was to become a totemic institution, Confederate Memorial Day. Mrs Williams, the daughter of a factory and railroad magnate, was married to a soldier who had, as Worsley writes, ‘served bravely in the war’. She composed ‘a beautiful letter’, which she had distributed to women, newspapers and charitable organisations throughout the South. Williams proposed

to set apart a certain day to be observed from the Potomac to the Rio Grande, and be handed down through time as a religious custom throughout the South, to wreath the graves of our martyred dead with flowers … Let every city, town and village join in the pleasant duty. Let all alike be remembered, from the heroes of Manassas to those who expired amid the death throes of our hallowed cause … They died for their country. Whether or not their country had or had not the right to demand that sacrifice is no longer a question for discussion. We leave that for nations to decide in the future. That it was demanded – that they fought nobly, and fell holy sacrifices upon their country’s altar, and are entitled to their country’s gratitude, none will deny.

Here was the core of Lost Cause mythology, what Blight describes as ‘deflections and evasions, careful remembering and necessary forgetting’, defined in a few sentences, as candid as they were succinct. If the true reason for the war was too painful to contemplate, then let it be dropped from discourse. Instead of asking whether all the devastation, loss and sacrifice had been justified, let them be venerated by the South’s revisionist history.

The seed sown in Columbus flourished and multiplied. By the end of the 1860s, there was barely a town which did not observe Mrs Williams’s ritual, with newly constructed memorial monuments, sometimes built in the greatly expanded cemeteries, as its focus. Similar observances began to be held in the North. Underlying them was a rhetoric of national reconciliation, of brotherhood renewed, in which Mrs Williams’s plea that the causes of the bloodshed be ‘no longer a question for discussion’ was accepted wholeheartedly. As the New York Herald put it in an editorial on Memorial Day 1877, ‘all the issues on which the war of the rebellion was fought seem dead’.

The only people written out of the script, in Columbus as elsewhere, were the former slaves. To them, in a Georgia stained by murder, exclusion, organised intimidation and a legal system of segregation that became more oppressive by the year, the issues for which the war had been fought did not seem dead at all. For black freedmen, reconciliation was possible only through submitting to white supremacy almost as completely as they had done before the torchlight parades and salutes that had heralded the war.

The Lost Cause legend did not die with the gradual entrenchment of civil rights, nor with the rise of a South where African-Americans have begun to serve as judges and elected politicians, and to gain access to business and social circles that were once impenetrably closed. In Columbus, hidden signs of a vision of the Confederacy as something heroic, a bulwark against the North’s alien values, lie as if woven into the streets. The local TV station, its logo reproduced on signs and billboards, is called WRBL – W-Rebel. It took a strike by black students in the 1980s to get the authorities at the local college (now Columbus State University) to see that to use ‘Johnny Rebel’ as the mascot for sports teams, black and white alike, and to ask them to parade before games to the strains of the Confederate anthem ‘Dixie’, was, at least for African-Americans, unacceptable.

On the shelves of the city’s bookstores I found the Lost Cause legend reproduced in an entire literary sub-genre of works such as The South Was Right, by James and Walter Kennedy, published in 2001. Railing against Northern historians’ ‘campaign of cultural genocide’, it maintains that the true story of the War Between the States is that ‘the free Southern nation was invaded, many of our people raped and murdered, private property plundered at will and their right of self-determination violently denied’.

Always lurking beneath Georgia’s surface, the strange and anachronistic wounded anger expressed by such discourse burst into the open in a protracted political struggle in the first years of the twenty-first century. In early 2001 I spent several weeks in Columbus, and daily studied the Ledger-Enquirer’s letters page. The State Assembly was debating a proposal to replace the Confederate battle flag as the official flag of the state, on the grounds that African-Americans saw it as a symbol of servitude and oppression; just as pertinently, transnational corporations which would otherwise have been investing in the state were expressing their reluctance unless the flag were changed. Not the least bizarre aspect of the debate was the fact that far from representing historical continuity, the Stars and Bars had only been readopted in 1956, as part of the state’s militant response to the US Supreme Court’s attempt to desegregate education. But to change the flag again, the Ledger-Enquirer’s incensed correspondents claimed, would be an intolerable act of vandalism.

‘The issue over the state flag is not altogether about heritage or hate or slavery. It is all about the blacks trying to force the white southerners to remove all symbols of the Confederacy from their sites, and they do not have the right to do that. If they choose to live in the South, they WILL have to look at it. Keep the flag flying!’ wrote Mr Danny Green. ‘The Confederate emblem should remain. There is [sic] no racial problems I know of. We gave blacks the right to ride in the front of the bus. Let’s not give them everything they want,’ added J.R. Stinson. A Mr Raymond King was more extreme: ‘Where does it end? It’s OK for a terrorist [sic], Jesse Jackson, to be revered as some kind of saint … but it’s not OK for us to honour our great Southern heritage. Bull! As far as I’m concerned, it’s the African-Americans that are full of hate because people like me will not bow down and give them a free ride in life.’

In 2001, the flag-reform measure passed. Almost two years later, a Republican candidate for State Governor named Sonny Perdue ended many decades of Democrat stewardship after making a pledge to restore the Confederate flag the central plank of his campaign.

I bought a copy of The South Was Right and took it home to England. It was only there, as I browsed one afternoon, that I noticed that someone had left a business card inside it, hidden between two pages. ‘National Alliance’, read a heading on the front, above a logo made up of a cross and oak leaves. ‘Towards a New Consciousness, a New Order; a New People’. Further details, complete with numbers for ‘Georgia hotlines’ and an address for a website, were printed on the reverse:

We believe that we have a responsibility for the racial quality of the coming generations of our people. That no multi-racial society is a healthy society. That if the White race is to survive we must unite our people on the basis of common blood, organize them within a progressive social order, and inspire them with a common set of ideals. That the time to begin is now.

I returned to Columbus in the autumn of 1998, two years after my first trip. This time, and for many subsequent visits, some of which lasted several weeks and others just a few days, my enquiries had a focus: the city’s most notorious series of crimes – the serial killings known as the ‘stocking stranglings’.

In the late 1970s, a time when Jimmy Carter’s arrival in the White House was being said to mark the emergence of a new, racially harmonious, post-civil rights ‘sunbelt’ South, the fabric of the city was rent by seven exceptionally horrible rapes and murders. The victims – the youngest fifty-nine, the oldest eighty-nine – were all white women who lived alone, and all were strangled, most with items of their own lingerie. All but one had lived in the neighbourhood of Wynnton, and some were members of the city’s highest social echelons. From an early stage, while he still rampaged without apparent hindrance, the Columbus authorities had been convinced that the perpetrator was black.

In the course of my research, I found myself keen to know more about the Big Eddy Club, the exclusive private social club on the banks of the Chattahoochee. The membership lists were confidential. But former staff told me that five of the women murdered by the strangler had been members or frequent visitors, together with many of the public officials whose job it became to capture and punish the man responsible for their deaths.

It took time, and the assiduous cultivation of local contacts, before I was able to acquire an invitation to venture beyond the big iron gates bearing the legend ‘B.E.’ that guard the entrance to the club’s driveway. My lunch, as the guest of a delightful, politically liberal couple who made me promise not to jeopardise their social standing by thanking them in print, was adequate, if not exceptional – a salmon filet with wilted greens, slightly overdone, and a chocolate torte with mixed berries for dessert. It would not have won a Michelin star, but on the other hand, I had been living amid the fast-food and chain restaurants of Columbus, and it was the tastiest meal I had eaten for weeks. The service – from a pair of young black waiters – was efficient and polite, without being over-attentive. As for the surroundings, as one gazed through the dining room’s panoramic windows at the scene of utter tranquillity, it was difficult to imagine that Columbus had a long history of violence.

After coffee in the lounge, I picked up my coat and made ready to leave. Elizabeth Senne, the maîtresse d’hôtel, saw me from the passageway and hurried over, detaining me at the door. She seemed awkward, agitated. ‘Please don’t make anything of the fact we haven’t got black members,’ she said, ‘and they do come as visitors. Really, they are very welcome.’ She touched my arm confidentially. ‘I think perhaps it’s the joining fee: it’s a lot to pay if you’re not sure you’re going to fit in.’

‘How much is it?’ I asked.

‘I can’t tell you that. But you know, most of the members are old families, and although newcomers are very welcome, there is a distinction. There is one guy who worked his way up from selling insurance. And although he’s seventy now, he’s still a newcomer. So maybe they sense that. You know what I mean?’

The joining fee, I discovered later that day, was $7,500. On her veranda that same evening, I described the club to my African-American friend Vicky Williams, and mentioned Elizabeth’s closing remarks. Vicky laughed, surprised at the way some people chose to spend their money, then came up with an alternative hypothesis. Mrs Senne, of course, was an employee: she could not be held responsible for following the club’s policies. But Vicky said, with a bitter little shrug, ‘It’s like, you’re a reporter, and you’re good at getting people to tell you their stories, and maybe you can tell when they’re lying. That’s how it is as a black person, when you encounter racism. People can seem ever so nice, but sometimes, you can smell it.’