Читать книгу Sterilization of Carrie Buck - David Smith - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

During October of 1927, Charles A. Lindbergh was in the final days of a sweep through all forty-eight states, completing a hero’s tour for his solo, nonstop, transatlantic flight. On the 19th, a rainy Wednesday, Lindbergh’s plane appeared out of a cloudy southwest sky and touched down at Logan Field in Baltimore, Maryland. Struggling from the plane, he was covered with a slicker to protect him in the open car and his triumphant parade through the downtown streets of the city began.

Ticker tape and drizzle mixed in the air as office workers craned their necks from windows to catch a glimpse of the “Lone Eagle,” America’s latest hero. The News in Lynchburg, Virginia reported that the crowds in Baltimore pressed so closely to the automobile in which Lindbergh was riding that police had difficulty keeping the way open.

October 19, 1927 was also a cloudy day in Lynchburg itself. At the State Colony for Epileptics and Feeble-minded, another historic event was occurring.

For this one, there would be no ticker tape and no parade.

There would be no celebration.

But the surgery performed that day at the hospital on the heights above Lynchburg would influence human history as surely as Lindbergh’s flight across the Atlantic.

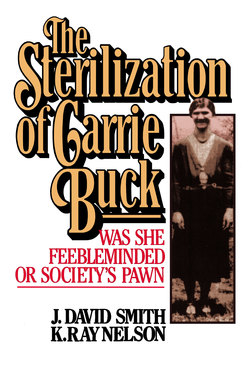

On that same early autumn day in 1927, a young woman named Carrie Buck was being sexually sterilized. Without her understanding of what was being done to her, or her agreement to allow the surgery, her capability to have children was taken away.

The operation to sterilize Carrie Buck came following the United States Supreme Court’s decision earlier that year, upholding the right of Virginia to impose sterilization upon any person judged to be mentally defective.

Carrie Buck was the subject of the test case leading to that decision.

Fifty years later, when reporters questioned how she’d felt, Carrie would reply, “They just told me I had to have an operation, that was all.”