Читать книгу Articles of Faith - David Wragg, David Wragg - Страница 13

SIX

ОглавлениеEvery part of Chel’s body hurt, from the scrapes to his face through to his burning side and battered middle, down to the sour and aching muscles of his legs. His right arm was strapped across his body, bound tight, and its shoulder throbbed with menace. Hot blood pounded against his temples like a three-day hangover. He was very thirsty.

He reeked of smoke, sweat and mule, and vague memories from the previous night floated through his wobbling mind. Flames, mostly, and blood. Firm hands, rough on his battered body, dragging him. Harsh voices and pain. The counts. The grand duke. The prince. Faces and shapes, unfamiliar, large and small. A mule. Bells.

He opened his eyes.

He was in a cramped store-room of sorts, piled with sacks and crates, with odd-pitching wooden walls. The only dim light came from a grille somewhere above, along with muted shouts and the occasional distant bell. The building around them seemed unsteady, as if it were shiftly slightly in a strong breeze. Someone beside him was snoring.

It was Tarfel, nestled beside him on a bed of lumpy sacks, still in the remains of his evening finery, soot-streaked and ragged. The prince stirred and whimpered in his sleep. He had a graze on his cheek, a nascent bruise beneath it, but looked otherwise unharmed. Chel guessed that the dark spatters on the prince’s silken shirt were from elsewhere. Chel wondered if he should let the prince sleep. He looked so pale and feeble, his mousy hair flopped over his scrawny features, his fringe puffed up on every out-breath.

Chel pushed himself to his feet and looked down at his own ruined clothes. The voluminous outer layers had been ripped away, leaving him in a dark snug tunic and trousers. He lifted his shirt to find the gash at his side bandaged, the skin around the dressing clear of crusted blood. Someone had cleaned his wounds and bound them, then left him here with the prince. That had to be a good omen. He tried to wring recollections from his brain. A woman’s voice, perhaps?

He glanced around, ignoring the complaints of his grumbling neck and shoulder. A glimmer of light along the base of one wall revealed a door. Chel tried the handle with his good hand. It was resolutely locked. With a sinking feeling, he returned to the prince.

‘Your highness? Prince Tarfel?’

Tarfel stirred, then rolled over. ‘I won’t!’ the prince said with remarkable clarity, and Chel blinked. ‘I won’t go! I don’t need lessons from those horrid old men.’

He mumbled on with decreasing coherence, before finishing with a half-garbled demand for the servants to bring fresh pillows. Chel blew the hair out of his eyes and pinched the bridge of his nose with his good hand. ‘Prince Tarfel!’

A rolling snore echoed around the store-room. Chel prodded the prince with a foot. He got no response.

Shouts echoed overhead, followed by thumps and clunks in the structure around them, then the whole building lurched into motion, rocking gently as it went. After a moment of unsteadiness, Chel collapsed onto a sack beside the prince. Of course it was a bloody boat. No smell of brine, no great lurching waves. They weren’t at sea. They must be on the river, and that had to mean Sebemir. The only questions were: where were they going, and who were they with?

Tarfel at last lifted his head, blinking in the gloom.

‘Whatever is going on?’ the prince said after a moment of dark, creaking quiet.

‘We’re on a boat, highness,’ Chel replied. ‘I think we’ve been kidnapped.’

‘Oh,’ the prince said. Then, after a moment, ‘What?’

‘Do you remember, highness? Someone tried to kill you last night, and someone else tried to kill me. Heali …’ Chel shook his head, numb at the memory. ‘The guards were gone, the Watch Commander with them, and those people in the palace weren’t Norts. Esen Basar killed his father, and I think he was trying to kill both of us. He had … he had a Nort mask, a pretend one. And … that pig-fucking beggar saved us.’ His shoulder pulsed at the memory. ‘But he ripped my arm out, and dragged us over the hills to what must be Sebemir, and now we’re locked in a cupboard on a riverboat. So I think it’s safe to assume that we’re still in trouble.’

‘Oh,’ the prince said. Then, after a moment, ‘What?’

***

For a time, Chel slept. He woke to the sound of raised voices beyond the door. The sky visible through the grille still offered the crimson streaks of sunset. It could not have been long. The prince was snoring again beside him, and Chel nudged him with his good arm.

‘Voices.’

Tarfel stirred and sat up. His bruise had darkened.

‘Who do you think they are?’ Chel said. ‘Those that took us.’

‘Oh, they’ll be mercenaries,’ the prince said with a grimace.

‘Not Rau Rel?’

‘Of course not, partisans would have murdered me immediately. You know, “death to tyrants” and all that nonsense.’ The prince shifted uncomfortably. ‘I imagine I’m to be ransomed. Question is, who would have the gall to order my abduction?’

‘Well, considering we’ve just seen Grand Duke Reysel murdered by his own son, perhaps the usual rules don’t apply right now, highness?’

The prince put one hand on his weak chin. ‘A little patricide isn’t uncommon, especially among northern Names. Notoriously emotional bunch, prone to hysteria.’

‘Morara and Esen meant to kill you, too, highness, and make it look like the Norts were responsible. Unless … Unless …’ Chel had told no one of the confessors beneath the Nort masks, but he had announced in front of Count Esen that he knew that the Norts were false. Had he doomed all those present in doing so? Was this his fault?

Tarfel ignored him. ‘Exactly, and now I’m kidnapped! Who would dare hold the kingdom to ransom?’

‘I’m not convinced that our kidnappers and your would-be assassins were working toward the same ends, highness.’ Seeing as one lot seem to have murdered the other.

‘Since Father’s Wars of Unity ended – the first time, at least – a few outposts of resistance to his rule have lingered: the southern territories, of course, the so-called free cities of the North, that grubby lot in the south-west … But none of them would risk bringing down the fury of the crown by stealing a prince.’

‘Are you sure it wasn’t the Rau Rel?’

‘Don’t be absurd. A gaggle of mud-farmers have no coin for mercenaries, even barely competent ones. Mud-farmers, dissidents, disgraced minor nobility, barely a name to their, er, name.’ He rubbed at his elbow, bruised from impact on a vegetable sack. ‘This was one of our continental rivals. They were imperial colonies when the Taneru ruled, and now witness their impudence. They shall pay for this, the moment I am freed. I shall not forget this insult.’

Chel nodded, turning away and rolling his eyes. ‘Of course, highness.’

Tarfel’s pout froze, gradually replaced by a faraway, fearful look. ‘Our bargain stands, doesn’t it? Chel? See me to safety, I’ll see you released.’

‘On my oath, highness. And if it’s really mercenaries on the other side of the door, maybe we can make them a better offer.’

Chel crept forward, feeling every ache of the damage the previous twenty-four hours had wrought on him, and pressed his ear to the door.

***

‘… cutting it fine, boss. Any finer we’d have been wafers.’ A rumbling, gentle voice. Peeved.

‘Not my choice. We had a run-in with some of our friends of the cloth.’ Chel remembered that voice: the beggar’s growl. He rubbed his good hand over his strapped shoulder and bared his teeth. So that was his kidnapper after all.

‘Ah, hells. I thought we’d be rid of the pricks at least.’

‘They had freelancers. Half a dozen horse-archers. Mawn if I’m any judge – and I am. They butchered some local militia they must have taken to be us.’

‘Twelve hells, boss, Mawn this far east?’

‘Forget it. We’re alive, and back on track. Despite enough cock-ups to leave a convent smiling.’

‘Ah, don’t be blaming me again, man!’ A reedy voice with a strong accent. Somewhere over the southern waters, Clyden most likely. ‘Told you before, friend Spider was covering while I took care of business. It’s not my fault I get tummy trouble, I’m delicate downstairs. You know, come to think it, could be a waterborne parasite from that last crossing. You ask me, it’s a wonder that we’re not laid low more frequently, given how often—’

‘Stop eating half-pickled fucking fish for breakfast, Lemon!’

‘I wasn’t the only one dropping bollocks out there, man! If Loveless could hold back on fucken every pretty thing she lays eyes on, we’d—’

Chel heard the creak and thump of the outer door.

‘We were just talking about you,’ the beggar said.

‘Nothing good, I hope,’ came the reply. ‘She’s aboard, by the way. In case you were worried.’

‘Not for a moment.’

‘No doubt. She wants a word. Or equivalent.’ The newcomer chuckled at that, for no clear reason.

Chel heard the beggar growl at the others and stomp away, then the groan of the door in his wake. All seemed quiet. He shifted, trying to catch something, when the bolt thunked and the door flew open. He pitched forward into an aching heap on the boards of the hold.

A sinewy, shaven-headed man with an aquiline nose and an abundance of earrings stood over him, a nasty grin on his face. He wore a tight, sleeveless tunic, exposing arms marked with a fearsome quantity of company tattoos. ‘Hello there, fuck-nuts. Having a good snoop, were we? Hear anything good?’ He rolled him over with the toe of his boot.

Chel said nothing for a moment, feeling his body throb beneath the pressure of the boot. Two other figures were in the low room, but he was struggling to make them out from where he was pinned. ‘Only,’ he said after a moment, his voice cracked, ‘that the little one should eat less fish.’

The bald man bellowed a laugh at that, as did the woman behind him.

‘Little one? Little? I’d wear your balls for earrings if you had any, chum,’ came the Clydish voice. ‘I’ve got a fucken name.’

Chel spread his good hand, still prone. The bald man’s foot hadn’t moved. ‘We’ve not been introduced.’

The man laughed again and removed his boot, then reached down with a muscular hand and dragged Chel upward until he was sitting against the wall. ‘Fair’s fair, now. Tell the sand-crab your names, boys and girls.’ He added under his breath, ‘Not like it’ll make much difference in the long run.’

A woman stepped forward from the gloom. She was the most striking woman Chel had ever seen: maybe a hand shorter than him, with a short shock of hair, alchemical blue, and a jawline so strong it could have been sculpted from marble. She kept one loose hand on the hilt of a short sword that hung from her hip. He had to wrench his gaze away from her, worried she’d think him simple.

‘Well, you’ve met the Spider here,’ she nodded at the bald man. Spider leered at him. Her accent was soft but distinct, something foreign but eroded to little more than uncommon vowels. ‘And the large and amiable gentleman back there is Foss.’

Behind her, a shape shifted against the wall, something Chel had at first glance taken to be a pile of sacks. He was enormous: big hands, big face, wide around the middle. He looked like a small hill. His hair was tied back in a thick bundle of dark braids, and his curly black beard boasted two streaks of grey at the corners of his chin. He offered Chel an awkward smile.

‘I go by Loveless,’ the blue-haired woman went on, ‘and this fine specimen of Clydish stock is Lemon.’

The final figure bowed her head in acknowledgement. She was small and wiry, her pale skin splashed copper with freckles. A mountain of orange hair bounced above a face that was round-eyed and squarish. She still looked irked.

Tarfel shuffled out of the store’s darkness beside and above him. ‘Why are you called Lemon?’

‘Because she’s round and bitter,’ Loveless said with a straight face.

‘I’m not fucken round!’

The laughter that filled the room met a sharp end when Spider rounded on the captives, his mirth vanished. ‘Now that’s enough about us. Who the fuck are you?’

‘I am Tarfel Merimonsun, Prince of—’

‘Oh, do shut up, princeling,’ Loveless said. ‘We know who you are, you blithering pillock. Why do you think you’re here?’

‘About that,’ Chel said, still sitting against the wall. His shoulder pulsed. He wondered if it had been Loveless who strapped him the night before. Perhaps it had been Lemon. Or maybe the other one they’d referred to?

‘The Spider asked you a question, Andriz piss-pot.’ Spider was still very close to him, and Chel could see the top of a freakish knife jutting from his belt. ‘Who are you, and what the fuck are you doing here?’

‘Vedren Chel, of Barva. I’m sworn to the prince.’

‘Chel?’ Loveless said. ‘What does that mean?’

‘I’m not sure it means anything. Do names always mean something?’

‘Oh, dear little scab-face, names mean everything.’

Lemon had wandered closer. ‘Got any nicknames? Any monikers or noms de guerre?’

‘Any what?’

‘Ah, come on, man. All our noms are de guerre these days. What do other people call you?’

Chel thought of the various names he’d been called over the last few years. ‘Chel.’

Tarfel pushed back into the conversation. He looked vexed at being excluded. ‘His sister calls him “Bear”!’

That got more sniggering. ‘You don’t look much like a fucking bear,’ Spider said. ‘More like a shit-eating rat. Are there rat-bears?’

‘I think there are in Tokemia,’ Lemon said.

Chel swung his sore head toward the prince. ‘Thank you, highness.’

Tarfel had the decency to look abashed, then a thought crossed his features before Chel’s eyes. ‘You’re not Rau Rel, are you?’ the prince said to the room.

More laughter. ‘No, princeling,’ Loveless said. ‘We’re mercenaries.’

Delight spread across Tarfel’s face. ‘See, Chel? Which company?’

The mercenaries exchanged cautious looks.

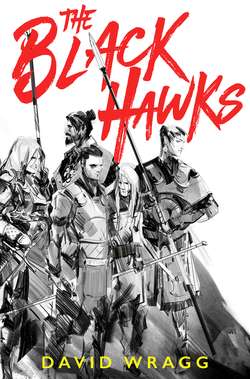

‘Black Hawk Company,’ Lemon said after a slight hesitation.

‘I’ve not heard of that one. How many strong are you? Two thousand? Five?’

Lemon looked around the room. ‘The second one.’

‘Five thousand?’

Lemon coughed. ‘Aye, well, we’re an incipient venture. Up-starting, if you will. Old hands, new pennant.’

‘Could I, by any chance, make you an offer?’ the prince said.

‘Only if you offer to fuck off back into that store and stay quiet until Kurtemir.’

Chel saw the big man, Foss, stiffen at that. He guessed that their destination was not intended to be divulged.

Spider was back at his ear, and this time the knife was in his hand. ‘The Spider notes with disappointment that you still haven’t answered his question. Why are you here, sand-crab rat-bear?’

Chel’s mouth felt suddenly dry, and he swallowed. ‘If you don’t know, I sure as snake-shit can’t tell you.’

‘He’s here because I want him here.’ No one had heard the door open this time, but there the old beggar stood, head ducked below the low lintel. He walked slowly into the hold and into the light. His rag-bundle clothes were streaked in grime: dust, soot, blood and who knew what else, his hair hanging in great ashen strings before his face. ‘Get to your duties. We’re not away clean yet.’

Foss gave him a sharp glance. ‘The river dock closed as we left it,’ he said in a low voice. ‘A sail?’

‘Not yet,’ the beggar said, then turned to the rest of the hold. ‘Was I mumbling? Get to it! Not you, Lemon – you’ll be keeping our friends company for now.’ Lemon started to protest, but he held up a hand. ‘You need the practice. The rest of you, out.’

As the other mercenaries shuffled out, the beggar marched to a water basin in the corner of the hold. He reached down and dragged his rotten clothes over his head, discarding layers of rags at his feet, then leaned forward and dunked his head. Chel watched through narrowed eyes as he splashed the water over himself, washing away coats of filth, then stood again, water cascading over his bared torso. Chel’s good hand was back on his ruined shoulder. Who was this brutal old bastard who had done him such damage?

The man before him had jet-black hair and skin the colour of sand, and was nowhere near as aged as Chel had thought. His body was sharp-edged and thickly muscled, and criss-crossed with more scarring and tattoos than Chel had ever seen on a single human. His upper arms cascaded with markings, some no doubt Free Company, but none Chel could distinguish or recognize. What kind of man could serve in that many companies anyway? An alarming collection of knives belted at the man’s waist glittered in the lantern light.

The beggar turned back to the hold, and at last Chel saw his face in the dim light. He was prow-faced, his nose a sharp, brutal beak, his dark and heavy features following in its wake. He seemed surprised that Chel and Tarfel were still there. He looked like a furious eagle.

He pinned Chel with a glare. ‘Got something you want to call me?’ Then he grinned, short and sharp. ‘Lemon! Get those fuckers locked away.’ With that, he scooped up a shirt and strode for the door.

A moment later the hold was empty, but for the disconsolate, muttering Lemon. ‘Aye, right. Practice, is it? Fuck’s sake, like I had any fucken alternative. Would he have me shit my breeches on duty? I ask you.’

Tarfel had already wandered back into the store in anticipation of being bolted away. Lemon checked over Chel’s bandages and strapping, while he lay piled where Spider had left him.

‘The tall one,’ Chel said. ‘With the nose. He’s the brains?’

‘The brains? Maybe the spleen, or wherever bile comes from. Right, you’ll live. Now get yourself back in there, wee bear, or ancestors-take-me I’ll fuck you right up with a hammer.’

Chel looked up at her. Buried in the matted fur and leather of Lemon’s outfit was an array of ironmongery, small hammers, axes and picks. ‘Are you a miner?’

She half smiled. ‘Once, maybe. In a sense.’

‘It doesn’t work, you know.’ It was Tarfel, from within the store’s gloom. ‘Your name, I mean.’

‘Oh aye?’

‘Lemons. They’re not bitter, they’re sour. That’s different.’

‘You’re telling fucken me! I’ve been telling those half-wits forever! Oh, but it’s all “Ah Lemon, what’s the difference, you’re a shite-heap either way”.’

Chel sensed an opening. Lemon seemed grateful to have someone to talk to. ‘They don’t sound like they’re very nice to you.’

Lemon frowned. ‘Are you joking? They’re the best bunch of bastards I ever rode with. Not that they know the value of an education, mind.’

‘You’re educated?’

‘I may not have attended a fancy Hacademy, but knowledge is power, wee bear, as the powerful know. Like me.’ She jabbed a thumb at herself. ‘For example, these folk we saw earlier today.’

‘Who? The prince and I didn’t really—’

‘Hush and listen, this could save your life some day.’

‘Oh?’

‘Aye, “oh”. See, thing is, most people, they don’t get hit by arrows much.’

‘That so?’

‘Indeedy. So, if and when they do, they don’t know what to do. They think that’s it, and they should just keel over, curl up their toes, back to the ancestors.’

‘Whereas …?’

‘Ah, you can fight on with an arrow in you! You can fight on with a dozen, like a fucken pin-cushion. I knew a fella, a Clydish man, mark you, not like one of you northern piss-sheets, fought on with sixteen arrows, two spears and a sword in him. Carried on for hours, cracking heads and ripping limbs.’

‘And he lived?’

‘Well, no, but he didn’t lie down and die at the first blow, did he?’

‘So what’s the big secret? If you’re hit by an arrow, don’t die?’

‘Aye. That’s the secret: don’t die. Now budge your skinny arse, before I help you along.’ She gave a meaningful wave with a fat-headed hammer, and Chel began to drag himself back into the store. The door closed behind them, and Lemon bolted it.

‘Hey, Lemon?’

‘What do you want, bugger-bear?’

‘What about the big guy? He got any names?’

‘Oh, Rennic? Hundreds. More than the rest of us combined.’

‘And what do you call him?’

‘We call him boss.’