Читать книгу The Broken God - David Zindell, David Zindell - Страница 8

CHAPTER TWO Danlo the Wild

ОглавлениеThe organism is a theory of its environment.

– Walter Wiener, Holocaust Century Ecologist

It took Danlo nine days to prepare for his journey. Five days he spent in his snowhut, recovering from his cutting. He begrudged every day of it because he knew that the sledding across the eastern ice would be dangerous and long. According to Soli’s stories, the Unreal City lay at least forty days away – perhaps more. Since it was already 82nd day in deep winter, he couldn’t hope to reach the City until the middle of midwinter spring. And midwinter spring was the worst season for travel. Who could say when a fierce sarsara, the Serpent’s Breath, would blow in from the north, heralding many days of blizzard? If the storms delayed his crossing too long, he might be stranded far out on the Starnbergersee when false winter’s hot sun came out and melted the sea ice. And then he and his dogs would die. No, he thought, he must find the City long before then.

And so, when he deemed himself healed, he went out to hunt shagshay. Skiing through the valleys below Kweitkel was now very painful, since every push and glide caused his membrum to chafe against the inside of his trousers. Pissing could be an agony. The air stung the exposed red tip of his membrum whenever he paused to empty himself. Even so he hunted diligently and often because he needed a lot of meat. (Ice fishing through a hole in the stream’s ice would have been an easier source of food, but he found that the fatfish were not running that year.) He cut the meat and scant blubber into rations; he sealed the rich blood into waterproof skins; he entered the cave and raided the winter barrels of baldo nuts. Into his sled went carefully measured packets of food. Into his sled, he carefully stowed his oilstone, sleeping furs, bag of flints, and bear spear. And, of course, his long, barbed whalebone harpoon. The dogs could pull only so much weight. Somewhere to the east they would finish the last of the food, and he would use the harpoon to hunt seals.

On the morning of his departure he faced the first of many hard decisions: what to do with the dogs? He would need only seven dogs to pull the sled: Bodi, Luyu, Kono, Siegfried, Noe, Atal, and his best friend, Jiro. The others, the dogs of Wicent and Jaywe, and the other families of the tribe, he would have to let loose. Or kill. After he had loaded his sled, he paused to look at the dogs staked out near their snow dens at the front of the cave. There were fifty-nine of them, and they were watching him with their pale blue eyes, wagging their tales and whining. In truth, he knew it was his duty to kill them, for how would they live without men to get their food and comfort them when they were sick or lonely? The dogs would flee barking into the forest, and they would pack and try to hunt. The wolves, however, were better hunters than the dogs; the silent wolves would track and circle them, and they would kill the dogs one by one. Or they would die of hunger, with folds of flesh hanging loosely over their bones. The dogs would surely die, but who was he to kill them? He thought it would be better for them to know a single additional day of life, even if that day were filled with pain and terror. He looked over the treetops into the sky. It was sharda, a deep, deep blue. The deep sky, the green and white hills, the smells of life – even a dog could love the world and experience something like joy. Joy is the right hand of terror, he told himself, and he knew he wouldn’t steal the dogs away from life. He nodded his head decisively. He smiled and trudged up through the powdery snow to set them free.

The last thing he did before leaving was to press his forehead against the bare rocks near the mouth of the cave. He did this because Manwe, on the twelfth morning of the world, had performed just such a gesture before setting out on his journey to visit all the islands of God’s new creation. ‘Kweitkel, narulanda,’ he said, ‘farewell.’

With a whistle to his sled dogs he began his journey as all Alaloi men do: slowly, cautiously schussing through the forest down to the frozen sea. There, beyond the beach of his blessed island, the icefields began. The gleaming white ice spread out in a great circle, and far off, at the horizon, touched the sky. It was the oldest of teachings to live solely for the journey, taking each moment of ice and wind as it came. But because he was still a boy with wild dreams, he couldn’t help thinking of the journey’s end, of the Unreal City. That he would reach the City, he felt certain, although in truth, it was a journey only a very strong man should contemplate making alone. There was a zest and aliveness about him at odds with all that had happened. He couldn’t help smiling into the sunrise, into the fusion fire glistering red above the world’s rim. Because he was hot with excitement, he had his snow goggles off and his hood thrown back. The wind lashed his hair; it almost tore away Ahira’s shining white feather. His face was brown against the white ruff of his hood. It was a young face, beardless and full of warmth and hope, but for all that, a strong, wild face cut with sun and wind and sorrow. With his long nose puffing steam and his high cheekbones catching the glint of the snowfields, there was a harshness there, softened only by his eyes. He had unique eyes, large and blue-black like the early evening sky. Yujena oyu, as the Alaloi say – eyes that see too deeply and too much.

Danlo handled the sled and guided the dogs across the ragged drift ice with skill and grace. Many times Haidar and he had made such outings, though they had never travelled very far from land. Six hundred miles of frozen sea lay before him, but he knew little of distances measured in this manner. For him and his panting dogs, each segment of ice crossed was a day, and each day rose and fell with the rhythm of eating, sledding, and sawing the blocks of snow that he shaped into a hut every night. And finally, after he had fed the dogs and eaten again himself, after he had slipped down into the silky warmth of his furs, sleep. He loved to sleep, even though it was hard to sleep alone. Often he would have bad dreams and cry out in his sleep; often he would awake sweating to see the oilstone burnt low and its light nearly extinguished. He always welcomed morning. It was always very cold, but always the air was clear, and the eastern sky was full of light, and the blessed mountain, Kweitkel, was every day vanishingly smaller behind him.

For twenty-nine days he travelled due east without mishap or incident. A civilized man making such a journey would have been bored by the monotony of ice and the seamless blue sky. But Danlo was not yet civilized; in his spirit he was wholly Alaloi, wholly taken with the elements of the world. And to his eyes there were many, many things to look at, not just sky and ice. There was soreesh, the fresh powder snow that fell every four or five days. When the wind blew out of the west and packed the snow so that it was fast and good for sledding, it became safel. The Alaloi have a hundred words for snow. To have a word for an object, idea or feeling is to distinguish that thing from all others, to enable one to perceive its unique qualities. For the Alaloi, as for all peoples, words literally create things, or rather, they create the way our minds divide and categorize the indivisible wholeness of the world into things. Too often, words determine what we do and do not see.

Ice and sky, sky and ice – when he awoke on the thirtieth morning of his journey, the ice surrounding his hut was ilka-so, frozen in a lovely, wind-driven ripple pattern. Farther out were bands of ilka-rada, great blocks of aquamarine ice heaved up by the contractions of the freezing sea. The sky itself was not purely blue; in places, at various times of the day, high above, there was a yellowish glare from light reflected off the snowfields. And the snowfields were not always white; sometimes, colonial algae and other organisms spread out through the top layers of snow and coloured it with violets and blues. These growths were called iceblooms, urashin, and Danlo could see the faint purple of the iceblooms off in the distance where the world curved into the sky. Kitikeesha birds were a white cloud above the iceblooms. The kitikeesha were snow eaters; at this time of the year, they made their living by scooping snow into their yellow bills and eating the snowworms, which in turn lived on the algae. (The furry, tunnelling sleekits, which could be found near any island or piece of land, also ate snow; sleekits would eat anything: algae, snowworms, or even snowworm droppings.) Danlo liked to stand with his hand shielding his eyes, looking at the iceblooms. Looking for Ahira. Sometimes, the snowy owls followed the kitikeesha flocks and preyed upon them. Ahira was always glad to sink his talons into a nice, plump kitikeesha chick, but on the thirtieth morning, Danlo looked for his doffel in vain. Ahira, he knew, was very wise and would not fly when a storm was near. ‘Ahira, Ahira,’ he called, but he received no reply. No direct reply, that is, no screeching or hooing or beating of wings. In silence, Ahira answered him. The Alaloi have five words for silence, and nona, the silence that portends danger, is as meaningful as a bellyful of words. In nona, Danlo turned his face to the wind and listened to things no civilized man could hear.

That day he did not travel. Instead, he cut snow blocks for a hut larger and sturdier than his usual nightly shelter. Into the hut he moved the food packets from the sled. He brought the dogs into the hut as well, bedding them down in the long tunnel that led to his living chamber. He made sure that there was snow to melt into drinking water and enough blubber to burn in the oilstone. And then he waited.

The storm began as a breath of wind out of the north. High wispy clouds called otetha whitened the sky. The wind blew for a long time, intensifying gradually into a hiss. It was the Serpent’s Breath, the sarsara that every traveller fears. Danlo listened to the wind inside his hut, listened as it sought out the chinks between the snowblocks and whistled through to strike at his soft, warm flesh. It was a cold wind, dead cold, so-named because it had killed many of his people. It drove glittering particles of spindrift into his hut. Soon, a layer of cold white powder covered his sleeping furs. The curled-up dogs were tougher than he, and didn’t really mind sleeping beneath a shroud of snow. But Danlo was shivering cold, and so he worked very hard to find and patch each chink with handfuls of malku, slush ice melted from the heat of his hand. After the malku had frozen in place – and this took only a moment – he could breathe more easily and settle back to ‘wait with a vengeance’, as the Alaloi say.

He waited ten days. It began snowing that evening. It was too cold to snow very much, but what little snow that the sky shed, the wind found and blew into drifts. ‘Snow is the frozen tears of Nashira, the sky,’ he told Jiro. He had called the dog closer to the oilstone and was playing tug-of-war with him. He pulled at one end of a braided leather rope while Jiro had the other end clamped between his teeth, growling and shaking his head back and forth. It was childish to pamper the dog with such play, but he excused himself from the usual travelling discipline with the thought that it was bad for a man – or a half-man – to be alone. ‘Today, the sky is sad because the Devaki have all gone over. And tomorrow too, I think, sad, and the next day as well. Jiro, Jiro, why is everything in the world so sad?’

The dog dropped the rope, whined, and poked his wet nose into his face. He licked the salt off of his cheeks. Danlo laughed and scratched behind Jiro’s ears. Dogs, he thought, were almost never sad. They were happy just to gobble down a little meat every day, happy sniffing the air or competing with each other to see who could get his leg up the highest and spray the most piss against the snowhut’s yellow wall. Dogs had no conception of shaida, and they were never troubled by it as people were.

While the storm built ever stronger and howled like a wolverine caught in a trap, he spent most of his time cocooned in his sleeping furs, thinking. In his mind, he searched for the source of shaida. Most of the Alaloi tribes believed that only a human being could be touched with shaida, or rather, that only a human being could bring shaida into the world. And shaida, itself, could infect only the outer part of a man, his face, which is the Alaloi term for persona, character, cultural imprinting, emotions, and the thinking mind. The deep self, his purusha, was as pure and clear as glacier ice; it could be neither altered nor sullied nor harmed in any way. He thought about his tribe’s most sacred teachings, and he asked himself a penetrating, heretical question: what if Haidar and the other dead fathers of his tribe had been wrong? Perhaps people were really like fragments of clear ice with cracks running through the centre. Perhaps shaida touched the deepest parts of each man and child. And since people (and his word for ‘people’ was simply ‘Devaki’) were of the world, he would have to journey into the very heart of the world to find shaida’s true source. Shaida is the cry of the world when it has lost its soul, he thought. Only, how could the world ever lose its soul? What if the World-soul were not lost, but rather, inherently flawed with shaida?

For most of a day and a night, like a thallow circling in search of prey, he skirted the track of this terrifying thought. If, as he had been taught, the world were continually being created, every moment being pushed screaming from the bloody womb of Time, that meant that shaida was being created, too. Every moment, then, impregnated with flaws that might eventually grow and fracture outward and shatter the world and all its creatures. If this were so, then there could be no evolution toward harmony, no balance of life and death, no help for pain. All that is not halla is shaida, he remembered. But if everything were shaida, then true halla could never be.

Even though Danlo was young, he sensed that such logical thinking was itself flawed in some basic way, for it led to despair of life, and try as he could, he couldn’t help feeling the life inside where it surged, all hot and eager and good. Perhaps his assumptions were wrong; perhaps he did not understand the true nature of shaida and halla; perhaps logic was not as keen a tool as Soli had taught him it could be. If only Soli hadn’t died so suddenly, he might have heard the whole Song of Life and learned a way of affirmation beyond logic.

When he grew frustrated with pure thought, he turned to other pursuits. He spent most of three days carving a piece of ivory into a likeness of the snowy owl. He told animal stories to the dogs; he explained how Manwe, on the long tenth morning of the world, had changed into the shape of the wolf, into snowworm and sleekit, and then into the great white bear and all the other animals. Manwe had done this magical thing in order to truly understand the animals he must one day hunt. And, too, because a man must know in his bones that his true spirit was as mutable as ivory or clay. Danlo loved enacting these stories. He was a wonderful mimic. He would get down on all fours and howl like a wolf, or suddenly rear up like a cornered bear, bellowing and swatting at the air. Sometimes he frightened the dogs this way, for it was no fun merely to act like a snow tiger or thallow or bear; he had to become these animals in every nuance and attitude of his body – and in his love of killing and blood. Once or twice he even frightened himself, and if he had had a mirror or pool of water to gaze into, it wouldn’t have surprised him to see fangs glistening inside his jaws, or fur sprouting all white and thick across his wild face.

But perhaps his favourite diversion was the study of mathematics. Often he would amuse himself drawing circles in the hard-packed snow of his bed. The art of geometry he adored because it was full of startling harmonies and beauty that arose out of the simplest axioms. The wind shifted to the northwest and keened for days, and he lay half out of his sleeping furs, etching figures with his long fingernail. Jiro liked to watch him scurf off a patch of snow; he liked to stick his black nose into a mound of scraped-off powder, to sniff and bark and blow the cold stuff all over Danlo’s chest. (Like all the Alaloi, Danlo slept nude. Unlike his near-brothers, however, he had always found the snowhuts too cold for crawling around without clothes, so he kept to his sleeping furs whenever he could.) It was the dog’s way of letting him know he was hungry. Danlo hated feeding the dogs, not only because it meant a separation from his warm bed, but because they were steadily running out of food. It pained him every time he opened another crackling, frozen packet of meat. He wished he had had better luck spearing fatfish for the dogs because fatfish were more sustaining than the lean shagshay meat and seemed to last longer. Though, in truth, he loathed taking dogs inside the hut whenever their only food was fish. It was bad enough that the hut already stank of rotten meat, piss, and dung. Having to scoop out the seven piles of dung which every day collected in the tunnel was bad indeed, but at least the dung was meat-dog-dung and not the awful smelling fish-dog-dung that the dogs themselves were reluctant to sniff. Nothing in the world was so foul as fish-dog-dung.

On the eighth morning of the storm, he fed them their final rations of food. His food – baldo nuts, a little silk belly meat, and blood-tea – would last a little longer, perhaps another tenday, that is, if he didn’t share it with the dogs. And he would have to share, or else the dogs would have no strength for sled pulling. Of course, he could sacrifice one of the dogs and butcher him up to feed the others, but the truth is, he had always liked his dogs more than an Alaloi should, and he dreaded the need for killing them. He whistled to coax the sun out of his bed and prayed, ‘O Sawel, aparia-la!’ But there was only snow and wind, the ragged, hissing wind that devours even the sun.

One night, though, there was silence. Danlo awakened to wonoon, the white silence of a new world waiting to take its first breath. He sat up and listened a while before deciding to get dressed. He slipped the light, soft underfur over his head, and then he put on his shagshay furs, his trousers and parka. He took care that his still sore membrum was properly tucked to the left, into the pouch his found-mother had sewn into his trousers. Next, he pulled his waterproof sealskin boots snug over his calves. Then he crawled through the tunnel where the dogs slept, dislodged the entrance snowblock, and stepped outside.

The sky was brilliant with stars; he had never seen so many stars. The lights in the sky were stars, and far off, falling out into space where it curved black and deep, points of light swirled together as densely as an ice-mist. The sight made him instantly sad, instantly cold and numinous with longing. Who could stare out into the vast light-distances and not feel a little holy? Who could stand alone in the starlight and not suffer the terrible nearness of infinity? Each man and woman is a star, he remembered. Many stars, such as Behira, Alaula, and Kalinda, he knew by name. To the north, he beheld the Bear, Fish, and Thallow constellations; to the west, the Lone White Wolf bared his glittering teeth. Two strange stars shined in the east, balls of white light as big as moons, whatever moons really were. (Soli had told him that the moons of the night were other worlds, icy mirrors reflecting the light of the sun, but how could this be?) Nonablinka and Shurablinka were strange indeed, supernovae that had exploded years ago in one of the galaxy’s spiral arms. Danlo, of course, understood almost nothing of exploding stars. He called them simply blinkans, stars which, from time to time, would appear from nowhere, burn brightly for a while and then disappear into the blackness from which they came. In the east, too, was the strangest light in the sky. It had no name that he knew, but he thought of it as the Golden Flower, with its rings of amber-gold shimmering just beyond the dark edge of the world. Five years ago, it had been born as a speck of golden light; for five years it had slowly grown outward, opening up into space like a fireflower. The various golden hues flowed and changed colour as he watched; they rippled and seemed alive with pattern and purpose. And then he had an astonishing thought, astonishing because it happened to be true: Perhaps the Golden Flower really was alive. If men could journey past the stars, he thought, then surely other living things could as well, things that might be like flowers or birds or butterflies. Someday, if he became a pilot, he must ask these strange creatures their names and tell them his own; he must ask them if they ached when the stellar winds blew cold or longed to join the great oceans of life which must flow outward toward the end of the universe, that is, if the universe came to an end instead of going on and on forever.

O blessed God! he prayed, how much farther was the Unreal City? What if he missed it by sledding too far north or south? Haidar had taught him to steer by the stars, and according to the stories, the Unreal City lay due east of Kweitkel. He looked off into the east, out across the starlit seascape. The drift ice and snowfields gleamed faintly; dunes of new snow rose up in sweeping, swirling shapes, half in silver-white and half lost in shadow. It was very beautiful, the cold, sad, fleeting beauty of shona-lara, the beauty that hints of death. Now the midwinter storms would blow one after the other, and snow would smother the iceblooms, which would die. And the snowworms would starve, and the sleekits – those who weren’t quick enough to flee to the islands – would starve, too. The birds would fly to miurasalia and the other islands of the north, because very soon, after the storms were done, the harsh sun would come out, and there would be no more snow or ice or starvation because there would be nothing left to starve.

Later that day, at first light, he went out to hunt seals. Each hooded seal – or ringed or grey seal – keeps many holes open in the sea ice; the ice of the sea, east and west, is everywhere pocked by their holes. But the holes are sometimes scarce and irregularly spaced. Snow always covers them, making them hard to find. Danlo leashed his best seal dog, Siegfried, and together they zigzagged this way and that across the pearl grey-snow. Siegfried, with his keen nose, should have been able to sniff out at least a few seal holes. But their luck was bad, and they found no holes that day. Nor the next day, nor the day after that. On the forty-third morning of his journey, Danlo decided that he must sled on, even though now he only had baldo nuts to eat and the dogs had nothing. It was a hard decision. He could stay and hope to find seals by searching the ice to the north. But if he wasted too many days and found no seals, the storms would come and kill him. ‘Ahira, Ahira,’ he said aloud, to the sky, ‘where will I find food?’ This time, however, his doffel didn’t answer him, not even in silence. He knew that although the snowy owl has the most far-seeing eyes of any animal, his sense of smell is poor. Ahira could not tell him what to do.

And so Danlo and his dogs began to starve in earnest. Even though he had eaten well all his life, he had heard many stories about starvation. And instinctively, he knew what it is like to starve – all men and animals do. When there is no food, the body itself becomes food. Flesh falls inward. The body’s various tissues are burnt like seal blubber inside a sac of loose, collapsing skin, burnt solely to keep the brain fresh and the heart beating a while longer. All animals will flee starvation, and so Danlo sledded due east into another storm, which didn’t last as long as the first storm, but lasted long enough. Bodi was the first dog to die, probably from a stroke fighting with Siegfried over some bloody, frozen wrappings he had given them to gnaw on. Danlo cut up Bodi and roasted him over the oilstone. He was surprised at how good he tasted. There was little life in the lean, desiccated meat of one scrawny dog, but it was enough to keep him and the remaining dogs sledding east into other storms. The snows of midwinter spring turned heavier and wet; the thick, clumpy maleesh was hard to pull through because it froze and stuck to the runners of the sled. It froze to the fur inside the dogs’ paws. Danlo tied leather socks around their cracked, bleeding paws, but the famished dogs ate them off and ate the scabs as well. Luyu, Noe, and Atal each died from bleeding paws, or rather, from the black rot that sets in when the flesh is too weak to fight infection. In truth, Danlo helped them over with a spear through the throat because they were in pain, whining and yelping terribly. Their meat did not taste as good as Bodi’s, and there was less of it. Kono and Siegfried would not eat this tainted meat, probably because they no longer cared if they lived or died. Or perhaps they were ill and could no longer tolerate food. For days the two dogs lay in the snowhut staring listlessly until they were too weak even to stare. That was the way of starvation: after too much of the flesh had fallen off and gone over, the remaining half desired nothing so much as reunion and wholeness on the other side of day.

‘Mi Kono eth mi Siegfried,’ Danlo said, praying for the dogs’ spirits, ‘alasharia-la huzigi anima.’ Again, he brought out his seal knife and butchered the dead animals. This time he and Jiro ate many chunks of roasted dog, for they were very hungry, and it is the Alaloi way to gorge whenever fresh meat is at hand. After they had finished their feast, Danlo cut the remaining meat into rations and put it away.

‘Jiro, Jiro,’ he said, calling his last dog over to him. With only the two of them left, the little snowhut seemed too big.

Jiro waddled closer, his belly bulging and distended. He rested his head on Danlo’s leg and let him scratch his ears.

‘My friend, we have had forty-six days of sledding and twenty-two days of storm. When will we find the Unreal City?’

The dog began licking his bleeding paws, licking and whining. Danlo coughed and bent over the oilstone to ladle out some hot dog grease melting in the pot. It was hard for him to move his arms because he was very tired, very weak. He rubbed his chest with the grease. He hated to touch his chest, hated the feel of his rib bones and wasted muscles, but everyone knew that hot grease was good for coughing fits. It was also good for frostbite, so he rubbed more grease over his face, over those burning patches where the dead, white skin had sloughed off. That was another thing about starvation: the body burnt too little food to keep the tissues from freezing.

‘Perhaps the Unreal City was just a dream of Soli’s; perhaps the Unreal City does not exist.’

The next day, he helped Jiro pull the sled. Even though it was lighter, with only twelve food packets stowed among the ice saw, sleeping furs, hide scraper, oilstone, it was still too heavy. He puffed and sweated and strained for a few miles before deciding to throw away the hide scraper, the spare carving wood and ivory, and the fishing lines. He would have no time for fishing now, and if he reached the Unreal City, he could make new fishing gear and the other tools he might need to live. He pulled the lightened sled with all his strength, and Jiro pulled too, pulled with his pink tongue lolling out and his chest hard against the leather harness, but they were not strong enough to move it very far or very fast. One boy-man and a starved dog cannot match the work of an entire sled team. The gruelling labour all day in the cold was killing them. Jiro whined in frustration, and Danlo felt like crying. But he couldn’t cry because the tears would freeze, and men (and women) weren’t allowed to cry over hardships. No, crying was unseemly, he thought, unless of course one of the tribe had died and gone over – then a man could cry an ocean of tears; then a true man was required to cry.

Soon, he thought, he too would be dead. The coming of his death was as certain as the next storm; it bothered him only that there would be no one left to cry for him, to bury him or to pray for his spirit. (Though Jiro might whine and howl for a while before eating the meat from his emaciated bones. Although it is not the Alaloi way to allow animals to desecrate their corpses, after all that had happened, Danlo did not begrudge the dog a little taste of human meat.)

‘Unreal City,’ he repeated over and over as he stared off into the blinding eastern snowfields, ‘unreal, unreal.’

But it was not the World-soul’s intention that Jiro eat him. Day by day the sledding became harder, and then impossible. It was very late in the season. The sun, during the day, burned too hotly. The snow turned to fareesh, round, granular particles of snow melted and refrozen each day and night. In many places, the sea ice was topped with thick layers of malku. On the eighty-fifth day of their journey, after a brutal morning of pulling through this frozen slush, Jiro fell dead in his harness. Danlo untied him, lifted him into his lap and gave him a last drink of water by letting some snowmelt spill out of his lips into the dog’s open mouth. He cried, then, allowing himself a time of tears because a dog’s spirit is really very much the same as a man’s.

‘Jiro, Jiro,’ he said, ‘farewell.’

He placed his hand over his eyes and blinked to clear them. Just then he chanced to look up from the snow into the east. It was hard to see, with the sun so brilliant and blinding off the ice. But through the tears and the hazy glare, in the distance, stood a mountain. Its outline was faint and wavered like water. Perhaps it wasn’t a mountain after all, he worried; perhaps it was only the mithral-landia, a traveller’s snow-delirious hallucination. He blinked and stared, and he blinked again. No, it was certainly a mountain, a jagged white tooth of ice biting the sky. He knew it must be the island of the shadow-men, for there was no other land in that direction. At last, perhaps some five or six days’ journey eastward, the Unreal City.

He looked down at the dog lying still in the snow. He stroked his sharp grey ears all the while breathing slowly: everything seemed to smell of sunlight and wet, rank dog fur.

‘Why did you have to die so soon?’ he asked. He knew he would have to eat the dog now, but he didn’t want to eat him. Jiro was his friend; how could he eat a friend?

He pressed his fist against his belly, which was now nothing more than a shrunken bag of acid and pain. Just then the wind came up, and he thought he heard Ahira calling to him from the island, calling him to the terrible necessity of life. ‘Danlo, Danlo,’ he heard his other-self say, ‘if you go over now, you will never know halla.’

And so, after due care and contemplation, he took out his knife and did what he had to. The dog was only bones and fur and a little bit of stringy muscle. He ate the dog, ate most of him that day, and the rest over the next several days. The liver he did not eat, nor the nose nor paws. Dog liver was poisonous, and as for the other parts, everyone knew that eating them was bad luck. Everything else, even the tongue, he devoured. (Many Alaloi, mostly those of the far western tribes, will not eat the tongue under any circumstances because they are afraid it will make them bark like a dog.) He made a pack out of his sleeping furs. From the sled he chose only those items vital for survival: the oilstone, snowsaw, his bag of carving flints, and bear spear. He strapped on his skis. Into the east he journeyed, abandoning his sled without another thought. In the Unreal City, on the island of the shadow-men, he could always gather whalebone and cut wood to make another sled.

In his later years he was to remember only poorly those next few days of skiing across the ice. Memory is the most mysterious of phenomena. For a boy to remember vividly, he must experience the world with the deepest engagement of his senses, and this Danlo could not do because he was weak of limb and blurry of eye and clouded and numb in his mind.

Every morning he slid one ski ahead of the other, crunching through the frozen slush in endless alternation; every night he built a hut and slept alone. He followed the shining mountain eastward until it grew from a tooth to a huge, snow-encrusted horn rising out of the sea. Waaskel, he remembered, was what the shadow-men called it. As he drew closer he could see that Waaskel was joined by two brother peaks whose names Soli had neglected to tell him – this half ring of mountains dwarfed the island. He couldn’t make out much of the island itself because a bank of grey clouds lay over the forests and the mountains’ lower slopes. It was at the end of his journey’s ninetieth day that the clouds began clearing and he first caught sight of the City. He had just finished building his nightly hut (it was a pity, he thought, to have to build a hut with the island so close, no more than half a day’s skiing away) when he saw a light in the distance. The twilight was freezing fast, and the stars were coming out, and something was wrong with the stars. At times, during flickering instants when the clouds billowed and shifted, there were stars below the dark outline of the mountains. He looked more closely. To his left stood the ghost-grey horn of Waaskel; to his right, across a silver, frozen tongue of water that appeared to be a sound or bay, there was something strange. Then the wind came up and blew the last clouds away. There, on a narrow peninsula of land jutting out into the ocean, the Unreal City was revealed. In truth, it was not unreal at all. There were a million lights and a thousand towering needles of stone, and the lights were burning inside the stone needles, burning like yellow lights inside an oilstone, yet radiating outward so that each needle caught the light of every other and the whole City shimmered with light.

‘O blessed God!’ Danlo muttered to the wind. It was the most beautiful thing he had ever seen, this City of Light so startling and splendid against the night time sky. It was beautiful, yes, but it was not a halla beauty, for something in the grand array of stone buildings hinted of pride and discord and a terrible longing completely at odds with halla.

‘Losas shona,’ he said. Shona – the beauty of light; the beauty that is pleasing to the eye.

He studied the City while the wind began to hiss. He marvelled at the variety and size of the buildings, which he thought of as immense stone huts flung up into the naked air with a grace and art beyond all comprehension. There were marble towers as bright as milk-ice, black glass needles, and spires of intricately carved granite and basalt and other dark stones; and at the edge of the sound where the sea swept up against frozen city, he beheld the glittering curves of a great crystal dome a hundred times larger than the largest snowhut. Who could have built such impossibilities, he wondered? Who could cut the millions of stone blocks and fit them together?

For a long time he stood there awestruck, trying to count the lights of the City. He rubbed his eyes and peeled some dead skin off his nose as the wind began to build. The wind cut his face. It hissed in his ears and chilled his throat. Out of the north it howled, blowing dark sheets of spindrift and despair. With his ice-encrusted mitten, he covered his eyes, bowed his head, and listened with dread to the rising wind. It was a sarsara, perhaps the beginning of a tenday storm. Danlo had thought it was too late in the season for a sarsara, but there could be no mistaking the sharpness of this icy wind which he had learned to fear and hate. He should go into his hut, he reminded himself. He should light the oilstone; he should eat and pray and wait for the wind to die. But there was no food left to eat, not even a mouldy baldo nut. If he waited, his hut would become an icy tomb.

And so, with the island of the shadow-men so near, he struck out into the storm. It was a desperate thing to do, and the need to keep moving through the darkness made him sick deep inside his throat. The wind was now a wall of stinging ice and blackness which closed off any light. He couldn’t see his feet beneath him, couldn’t get a feel for the uneven snow as he glided and stumbled onward. The wind cut his eyes and would have blinded him, so he squinted and ducked his head. Even though he was delirious with hunger, he had a plan. He tried to ski straight ahead by summoning up his sense of dead reckoning (so-called because if he didn’t reckon correctly, he would be dead). He steered straight toward the bay that separated the mountain, Waaskel, from the City. If it were the World-soul’s intention, he thought, he would find the island. He could build a hut beneath some yu trees, kill a few sleekits, rob their mounds of baldo nuts, and he might survive.

He skied all night. At first, he had worried about the great white bears that haunt the sea ice after the world has grown dark. But even old, toothless bears were never so desperate or hungry that they would stalk a human being through such a storm. After many long moments of pushing and gliding, gliding and pushing, he had neither thought for bears, nor for worry, nor for anything except his need to keep moving through the endless snow. The storm gradually built to a full blizzard, and it grew hard to breathe. Particles of ice broke against the soft tissues inside his nose and mouth. With every gasp stolen from the ferocious wind, he became weaker, more delirious. He heard Ahira screaming in the wind. Somewhere ahead, in the sea of blackness, Ahira was calling him to the land of his new home. ‘Ahira, Ahira!’ He tried to answer back, but he couldn’t feel his lips to move them. The blizzard was wild with snow and death; this wildness chilled him inside, and he felt a terrible urge to keep moving, even though all movement was agony. His arms and legs seemed infinitely heavy, his bones as dense and cold as stone. Only bone remembers pain – that was a saying of Haidar’s. Very well, he thought, if he lived, his bones would have much to remember. His eye sockets hurt, and whenever he sucked in a frigid breath, his nose, teeth, and jaw ached. He tried each moment to find the best of his quickness and strength, to flee the terrible cold, but each moment the cold intensified and hardened all around him, and through him, until even his blood grew heavy and thick with cold. Numbness crept from his toes into his feet; he could barely feel his feet. Twice, his toes turned hard with frostbite, and he had to stop, to sit down in the snow, bare each foot in turn, and thrust his icy toes into his mouth. He had no way to thaw them properly. After he had resumed pushing through the snowdrifts, his toes froze again. Soon, he knew, his feet would freeze all the way up to his ankles, freeze as hard as ice. There was nothing he could do. Most likely, a few days after they were thawed, his feet would run to rot. And then he – or one of the City’s shadow-men – would have to cut them off.

In this manner, always facing the wind that was killing him, or rather, always keeping the wind to his left, to the frozen left side of his face, by the wildest of chances, he came to land at the northern edge of Neverness. A beach frozen with snow – it was called the Darghinni Sands – rose up before him, though in truth he could see little of it. A long time ago morning had come, a grey morning of swirling snow too thick to let much light through. He couldn’t see the City where it loomed just beyond the beachhead; he didn’t know how near were the City’s hospices and hotels. Up the snow-encrusted sands he stumbled, clumsy on his skis. Once, he clacked one ski hard against the other and almost tripped. He checked himself by ramming his bear spear into the snow, but the force of his near fall sent a shooting pain into his shoulder. (Sometime in the night, while he was thawing his toes for the third time, he had set his poles down and lost them. It was a shameful lack of mindfulness, a mistake a full man would never make.) His joints clicked and ground together. He made his way over the wind-packed ridges of bureesha running up and down the length of the beach. Little new snow had accumulated on the island; the wind, he knew, must have blown it away. The bureesha was really bureldra, thick old ribs of snow too hard for skiing. He would have taken his skis off, but he was afraid of losing them, too. He peered through the white spindrift swirling all around him. It was impossible to see more than fifty feet in any direction. Ahead of him, where the beach ended, there should be a green and white forest. If he were lucky, there would be yu trees with red berries ready for picking. And stands of snow pine and bonewood thickets, birds and sleekits and baldo nuts. From somewhere beyond the cloud of blinding snow, Ahira called to him. He thought he could hear his father, the father of his blood, calling, too. He stumbled on in a wild intensity of spirit far beyond pain or cold or the fear of death. At last he fell to the snow and cried out, ‘O, Father, I am home!’

He lay there for a long time, resting. He didn’t really have the strength to move any further, but move he must or he would never move again.

‘Danlo, Danlo.’

Ahira was still calling him; he heard his low, mournful hooing carried along by the wind. He rose slowly and moved up the beach toward Ahira’s voice. Closer he came, and the sound drew out, piercing him to the bone. His senses suddenly cleared. He realized it wasn’t the voice of the snowy owl at all. It was something else, something that sounded like music. In truth, it was the most beautifully haunting music he had ever imagined hearing. He wanted the music to go on forever, on and on, but all at once, it died.

And then, at the head of the beach, through the spin-drift, he beheld a fantastic sight: a group of six men stood in a half-circle around a strange animal unfamiliar to Danlo. Strange are the paths of the Unreal City, he reminded himself. The animal was taller than any of the men, taller even than Three-Fingered Soli, who was the tallest man he had ever seen. He – Danlo could tell that the animal was male from the peculiar-looking sexual organs hanging down from his belly – he was rearing up on his hind legs like a bear. Why, he wondered, were the men standing so close? Didn’t they realize the animal might strike out at any instant? And where were their spears? Danlo looked at the men’s empty hands; they had no spears. No spears! he marvelled, and even though they were dressed much as he was, in white fur parkas, they wore no skis. How could these shadow-men hunt animals across snow using neither spears nor skis?

Danlo approached as quietly as he could; he could be very quiet when he had to be. None of the men looked his way, and that was strange. There was something about the men’s faces and in their postures that was not quite right. They were not alert, not sensitive to the sounds or vibrations of the world. The animal was the first to notice him. He was as slender as an otter; his fur was white and dense like that of a shagshay bull. He stood too easily on his legs. No animal, Danlo thought, should be so sure and graceful on two legs. The animal was holding in his paw some kind of stick, though Danlo couldn’t guess what an animal would be doing with a stick, unless he had been building a nest when the men surprised him. The animal was staring at Danlo, watching him in a strange and knowing manner. He had beautiful eyes, soulful and round and golden like the sun. Not even Ahira had such large eyes; never had Danlo seen eyes like that on any animal.

He moved closer and drew back his spear. He couldn’t believe his good luck. To find a large meat animal so soon after his landfall was very good luck indeed. He was very hungry; he prayed that he would have the strength to cast the spear straight and true.

‘Danlo, Danlo.’

It was strange the way the animal stood there watching him, strange that he hadn’t fled or cried out. Something had cried out, though. He thought it must be Ahira reminding him that he was required to say a silent prayer for the animal’s spirit before he killed him. But he didn’t know the animal’s name, so how could he pray for him? Perhaps the Song of Life told the names of the Unreal City’s strange animals. For the thousandth time, he lamented not hearing the whole Song before Soli had died.

Just then, one of the men turned to see what the animal was staring at. ‘Oh!’ the man shouted, ‘oh, oh, oh!’

The other men turned too, looking at him with his spear arm cocked, and their eyes were wide with astonishment.

Danlo was instantly in shock. He could finally see that Soli had told the truth. The shadow-men’s faces were much more like his own lean, beardless face than the rugged Alaloi faces of his near-fathers. And here was the thought that shocked and shamed him: what if the animal were imakla? What if these beardless men knew the animal was imakla and may not be hunted under any circumstances? Wouldn’t the men of the City know which of their strange animals was a magic animal and which was not?

‘No!’ one of the men shouted, ‘no, no, no!’

Danlo was ravenous, exhausted, and confused. Because of the wind and the spindrift stinging his eyes, he was having trouble seeing. He stood with his spear held back behind his head. His whole body trembled, and the spearpoint wavered up and down.

Many things happened all at once. Slowly, the animal opened his large, mobile lips and began making sounds. The man who had shouted, ‘Oh!’ shouted again and flung himself at the animal, or rather, tried to cover him with his body. Three of the others ran at Danlo, shouting and waving their arms and hands. They grabbed him and wrenched the spear from his hand. They held him tightly. They were not nearly so strong as Alaloi men, but they were still men, still strong enough to hold a starved, frightened boy.

One of the men holding him – remarkably, his skin was as black as charred wood – said something to the animal. Someone else was shouting, and Danlo couldn’t make out what he said. It sounded like gobbledygook. And then, still more remarkably, the animal began to speak words. Danlo couldn’t understand the words. In truth, he had never thought there might be languages other than his own, but he somehow knew that the animal was conversing in a strange language with the men, and they with him. There was a great yet subtle consciousness about this animal, a purusha shining with the clarity and brilliance of a diamond. Danlo looked at him more closely, at the golden eyes and especially at the paws that seemed more like hands than paws. Was he an animal with a man’s soul or a man with a deformed body? Shaida is the way of the man who kills other men. O blessed God! he thought again, he had almost killed that which may not be killed.

‘Lo ni yujensa!’ Danlo said aloud. ‘I did not know!’

The animal walked over to him and touched his forehead. He spoke more words impossible to understand. He smelled of something familiar, a pungent odour almost like crushed pine needles.

‘Danlo los mi nabra,’ Danlo said, formally giving the animal and the men his name. It was his duty to trade names and lineages at the first opportunity. He tapped his chest with his forefinger. ‘I am Danlo, son of Haidar.’

The black man holding him nodded his head severely. He poked Danlo in the chest and nodded again. ‘Danlo,’ he said. ‘Is that what they call you? What language are you speaking? Where did you come from that you can’t speak the language of the Civilized Worlds? Danlo the Wild. A wild boy from nowhere carrying a spear.’

Danlo, of course, understood nothing of what the man said, other than the sound of his own name. He didn’t know it was a crime to brandish weapons in the City. He couldn’t guess that with his wind-chewed face and his wild eyes, he had frightened the civilized men of Neverness. In truth, it was really he who was frightened; the men held him so tightly he could hardly breathe.

But the animal did not seem frightened at all. He was scarcely perturbed, looking at him in a kindly way and smiling. His large mouth fell easily into a kind of permanent, sardonic smile. ‘Danlo,’ he repeated, and he touched Danlo’s eyelids. His fingernails were black and shaped like claws, but otherwise his exceedingly long hands were almost human. ‘Danlo.’

He had almost killed that which may not be killed.

‘Oh, ho, Danlo, if that is your name, the men of the City call me Old Father.’ The animal-man placed his hand flat against his chest and repeated, ‘Old Father.’

More words, Danlo thought. What good were words when the mind couldn’t make sense of words? He shook his head back and forth, and tried to pull free. He wanted to leave this strange place where nothing made sense. The shadow-men had faces like his own, and the animal-man spoke strange, incomprehensible words, and he had almost killed that which may not be killed and therefore almost lost his soul.

Shaida is the cry of the world when it has lost its soul, he remembered.

The man-animal continued to speak to him, even though it was clear that Danlo couldn’t understand the words. Old Father explained that he was a Fravashi, one of the alien races who live in Neverness. He did this solely to soothe Danlo, for that is the way of the Fravashi, with their melodious voices and golden eyes, to soothe and reflect that which is most holy in human beings. In truth, the Fravashi have other ways, other reasons for dwelling in human cities. (The Fravashi are the most human of all aliens, and they live easily in human houses, apartments, and hospices so long as these abodes are unheated. So human are they, in their bodies and in their minds, that many believe them to be one of the lost, carked races of man.) In truth, the men surrounding Old Father were not hunters at all, but students. When Danlo surprised them with his spear, Old Father had been teaching them the art of thinking. Ironically, that morning in the blinding wind, he had been showing them the way of ostrenenie, which is the art of making the familiar seem strange in order to reveal its essence, to reveal hidden relationships, and above all, truth. And Danlo, of course, understood none of this. Even if he had known the language of the Civilized Worlds, its cultural intricacies would have escaped him. He knew only that Old Father must be very kind and very wise. He knew it suddenly deep in his aching throat, knew it with a direct, intuitive knowledge that Old Father would call buddhi. As Danlo was to learn in the coming days, Old Father placed great value on buddhi.

‘Lo los sibaru,’ Danlo said. Unintentionally, he groaned in pain. All the way up to his groin, his legs felt as cold as ice. ‘I’m so hungry – do you have any food?’ He sighed and slumped against the arms of the men still holding him. Speech was useless, he thought. ‘Old Father’ – whatever the incomprehensible syllables of that name really meant – couldn’t understand the simplest of questions.

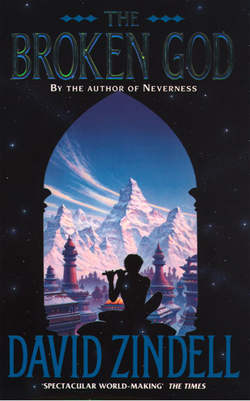

Danlo was beginning to fall into the exhausted stupor of starvation when Old Father brought his stick up to his furry mouth and opened his lips. The stick was really a kind of long bamboo flute called a shakuhachi. He blew into the shakuhachi’s ivory mouthpiece. And then a beautiful, haunting music spread out over the beach. It was the same music Danlo had followed earlier, a piercing, numinous music at once infinitely sad yet full of infinite possibilities. The music overwhelmed him. And then everything – the music, the alien’s strange new words, the pain of his frozen feet – became unbearable. He fainted. After a while, he began to rise through the cold, snowy layers of consciousness where all world’s sensa are as hazy and inchoate as an ice-fog. He was too ravished with hunger to gain full lucidity, but one thing he would always remember: astonishingly, with infinite gentleness, Old Father reached out to open his clenched fist and then pressed the shakuhachi’s long, cool shaft into his hand. He gave it to him as a gift.

Why? Danlo wondered. Why had he almost killed that which may not be killed?

For an eternity he wondered about all the things that he knew, wondered about shaida and the sheer strangeness of the world. Then he clutched the shakuhachi in his hand, closed his eyes, and the cold dark tide of unknowing swept him under.