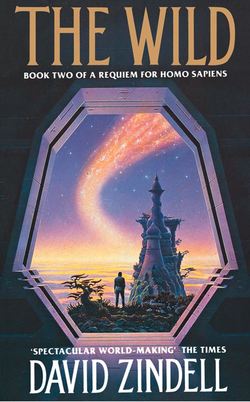

Читать книгу The Wild - David Zindell, David Zindell - Страница 9

CHAPTER FOUR The Tiger

ОглавлениеTyger! Tyger! burning bright

In the forests of the night,

What immortal hand or eye,

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?

– William Blake

The next day Danlo moved into the house. As a pilot he had few possessions, scarcely more than fit in the plain wooden chest that he had been given when he had entered the Order seven years since. With some difficulty, he tied climbing ropes to this heavy chest and dragged it from his ship across the beach dunes up to the house. He stowed it in the fireroom. There, on fine rosewood racks near the fireplace, he hung up his black wool kamelaikas to air. Out of his trunk he also removed a rain robe to wear against the treacherous weather which fell over the shore in sudden squalls or the longer storms of endless downpours and great crashing waves of water. He was content to leave most of the contents of his trunk where they lay: the diamond scryers’ sphere that had once belonged to his mother; his ice skates; his carving tools; and a chess piece of broken ivory that he had once made for a friend. But he found much use for one of the books buried deep in the trunk. This was a book of ancient poems passed on from the erstwhile Lord of the Order to Danlo’s father. Mallory Ringess, as everyone knew, had memorized many of these poems; his love of dark, musical words and subtle rhymes had helped him survive the poetry game during his historic journey into the Solid State Entity. Danlo liked to sit before the blazing logs of the fireplaces, reading these primitive poems and remembering. He spent much of his time during the first few days simply sitting and reading and meditating on the terrible fluidity of fire. Often, as he watched the firelight knot and twist, he longed for other fires, other places, other times. Just as often, though, he descried in the leaping flames the passion and pattern of his own fate: he would survive whatever tests the Entity put to him, and he would continue his journey across the stars. At these times, while he listened to the sheets of rain drumming against the windows and roof, he fell lonely and aggrieved. Only then would he search his trunk for the most cherished of all the things he owned: a simple bamboo flute, an ancient shakuhachi smelling of woodsmoke and salt and wild ocean winds. He liked to play this flute sitting crosslegged in front of the fire or standing by the windows of the meditation room above the sea. Its sound was high and fierce like the cry of a seabird; in playing the sad songs he had once composed, he sensed that the Entity was aware of every breath he took and could hear each long, lonely note. And it seemed that She answered him with a deeper music of rushing wind and thunderous surf and the strange-voiced whales and other animals who called to each other far out at sea. The Entity, he supposed, could play any song that She wished, upon the rocks and the sand, or in the rain-drenched forest, or in all the rushing waters of the world. He sensed that the Entity was preparing a special song to play to him. He dreaded hearing this song, and yet he was eager for the sound of it, like a child struggling to apprehend the secret conversations of full men. And so he played his flute through many days, played and played, and waited for the goddess to call him to his fate.

Of course, he did not really need forty days to regain his strength. He was young and full of fire and all the quickness of young life. He spent long nights sleeping on top of furs in the fireroom and longer days in the kitchen eating. In the food bins and pretty blue jars he found much to eat: black bread and sweet butter and soft spreading cheeses; tangerines and bloodfruits; almond nuts and lychees and filberts – and seeds from tens of plants and trees wholly unfamiliar to him. He found, too, a bag of coffee beans which he roasted until they were black and shiny with oil and then ground to a rich, bittersweet powder. Sometimes he would arise too early in the morning and drink himself into the sick clarity of caffeine intoxication. He remembered, then, his natural love of drugs. Once a time, he had drunk coffee and toalache freely, but he had especially loved the psychedelics made from cacti, kallantha, mushrooms, and the other spirit foods that grew out of the earth. However, as he also remembered, he had forsworn the delights of all drugs, and so he abandoned his coffee drinking in favour of cool mint teas sweetened with honey. Each day he would spend hours in the tea room sipping from a little blue cup and gazing out to sea.

One morning he remembered the keenest stimulation of all, which was walking alone in the wild. The beach outside the house and the dark green forest above were truly as wild as any he had ever seen. When his legs had hardened against the gravity of this Earth, he took to walking for miles up and down the windy beach. He left deep boot prints in the sand along the water’s edge, and sensed that no other human being had ever walked here before him. He might have fallen lonely at his isolation, and in a way he did. But in another and deeper way, it was only by being alone that he could search out his true connection with the other living things of the world. He remembered a line from a poem: Only when I am alone am I not alone. All around him – along the shore rocks and the fir trees and grassy dunes – there was nothing but other life. His were not the only tracks in the sand. At times he liked nothing better than reading the sandprints of the various animals that walked the beach with him. In the hardpack he could often make out the skittering marks of the sandpipers and the sea turtles’ deep, wavy grooves. There were the scratchy lines of the crabs and the bubbling holes of the underground crustacea buried beneath the wet sand. Once, higher up the beach at the edge of the forest, he found the paw prints of a tiger. They were wide and distinct and pressed deeply into the soft dunes. He knew this spoor immediately for what it was. Many times, as a boy, he had read the tracks of tigers. Certainly, he thought, the snow tigers that stalked the islands west of Neverness would be of a different race than this slightly smaller tiger of the forest, but a tiger was always a tiger.

If Danlo had any doubt as to the evidence of his eyes, one day he heard a lone male roaring deep in the forest. The tiger, he estimated from his throaty sound, was at least a mile away. Perhaps he was calling the she-tigers to mate with him or calling other males to share his kill. Danlo suddenly remembered, then, how certain tigers sometimes hunted men. Because he had no wish to meet a hungry tiger on the open beach, he thought to arm himself with drug darts or sound bombs or lasers. But he was a pilot, after all, not a wormrunner, and his ship carried no such weapons. He might have made a spear out of whalebone and wood, but he remembered that his vow of ahimsa forbade him to harm any animal, even a desperate tiger, even in defence of his own blessed life. The most prudent course of action would have been to keep to the house while waiting for the days to pass until his test. But this he could not do. And so in the end, on his daily walks along the beach, he began carrying a long piece of driftwood that he found. He would never, of course, use this as a club to beat against living flesh. If he encountered a tiger he would only brandish this ugly stick, waving it about and shouting like a madman in hope of scaring the beast away.

The presence of tigers on this lovely beach reminded Danlo of the dark side of nature. It reminded him of the dark side of himself. All his life he had seen a marvellous consciousness in all things, in sand and trees as well as the intelligent animals with their bright yellow eyes. But consciousness itself was not all sunlight and flowers; in the essence of pure consciousness there was something other, something dangerous and dark like the swelling of the sea beneath the bottomless winter moon. All things partook of this danger. And if he was of the world, then so did he. Because he was a man, like other men, he sometimes wanted to deny this knowledge of himself. Sometimes, when he grew faithless and weak, he was tempted to see himself as a golden and godlike creature forced merely to live in the world until he might complete his evolution and make a better world – either that or transcend the darkness of rocks and blood and matter altogether. But always, when he opened the door of his house and stepped outside into the shock of the cold salt air, he returned to himself. That was the magic of all wild places. Always, at the edge of the ocean, there was a wakefulness, a watching and a waiting. All the animals, he thought – the kittiwakes and seagulls, the otters and whelks and orcas – were always calling to each other with a curious, wary excitement, waiting to touch each other with eyes or tongues or their glittering white teeth. Life always longed to envelope other life, to hold, to taste, to merge tissue upon tissue and consume other things. He saw this down in the tidepools, the way the crabs patiently used their strong claws to break open the razor clams a bit of shell at a time. He saw it in the way the great orange sea-stars clasped the mussels in their five strong arms and slowly suctioned them open, and then, with an almost sexual strategem, extruded their stomachs through their mouths in order to envelope the naked mussels inside their shells and digest them. All life trembled with a terrible love for all other living things, and sometimes this love was almost hate, not the simple loathing of a man for the dirt and gore of organic life, but rather the deep and true hate of being abandoned and lost and utterly consumed. The bone-melting ferocity with which nature was always trying to consume itself was truly an awesome thing. To be slain and eaten and absorbed by a fierce animal was the terror that all creatures must face, but being absorbed into the participation with all other life was the joy and wildness of the world. This sense of oneness with other life, he thought, was the essence of love. He saw love in the dance of the bee and flower and in the way that the algae and fungi combined to form the symbiotic lichens that grew over the rocks in bright bursts of ochre and orange. It was as if life, in its longing to love, must continually seek out other living things in order to share its nectar, its secrets, its memories, its wonderful sense of being alive.

But for a man, that glorious and doomed being halfway between ape and god, it was always too possible to fall out of love. Always, for all men and women across all the worlds of the galaxy’s many stars, there was the danger of living along the knifeblade edge between a craven terror of nature and the urge to isolate oneself from the world, ultimately to dominate and destroy it. Along this fine and terrible edge was the wildness of the soul, its nobility and passion, neither cowering nor controlling but simply living, bravely, freely, like a sparrowhawk racing along the wind. This was the challenge of the wild. But few human beings have ever dared to live this way. For it is only in accepting death that one can truly live, and for the human animal, death has always been the great black beast from the abyss to be dreaded or defeated or avoided or hated – but never looked upon clearly face to face.

If Danlo was able to see the darkness (and splendour) of life more deeply than most men, this gift had been won at great cost. As a child he had grown up within the fear of ice and wind and the cunning white bears that stalked the islands of his home. As a young man he had suffered wounds and sacrificed part of his flesh that he might face the world as a full man. And once, on a night of broken lips and blood, he had taken a vow of ahimsa. Many thought of ahimsa as merely a strict moral code that forbade people to harm other life; as a tight, silky cocoon of words and conceits that restricted one’s actions and yet allowed a man to feel superior to others. But for Danlo, ahimsa was pure freedom. Although the keeping of his vow sometimes required tremendous will, his reward was the fearlessness of life and more, the greatest reward of all, to share in its joy. There was a word that Danlo remembered, animajii, wild joy, life’s overflowing delight in itself. Along this cold, misty shore, he sensed animajii everywhere, in the red cedars and hemlock trees straight and silent as spires, in the death-cup mushrooms and earthstars, in the butterflies and spiders and waterworms, and perhaps most of all, in the great whales that dove beneath the ocean’s waves. He loved looking out to sea as the sun died and melted over the golden waters. All too often he stood frozen and helpless on soft sands as he drank in all this wild joy around him and marvelled that the Entity could have made this Earth so perfectly. The goddess, he thought, must surely know all there was to know about joy, about beauty, about men, about life.

One day, late on the forty-first afternoon of his sojourn on the planet, a distant sound far off in the heavens startled him out of his usual ritual of drinking peppermint tea. At first he thought it was thunder, not the omnipresent thunder of the crashing surf but rather that of lightning and ozone and superheated air. When he looked out the window at the heavy grey clouds hanging low over the sea, he thought that this might be the beginning of a storm. But when he listened more closely, he heard a great rolling sound more like drum music than thunder, as if the whole of the sea was booming out low, deep, angry notes that reverberated from horizon to shore. Then the terrible sound intensified, shaking the house and rattling the windows. Because Danlo remembered other windows in other places, he quickly covered his face with his hands lest the glass suddenly shatter inward. And then, a moment later, the thunder died into a whisper. Turn his head as he might, from right to left, from left to right, he could not divine the source of this whisper. It seemed to float along the beach and fall down over him from the skylights in the roof; he heard the whisper of wind whooshing down the blackened fireplace, and then a strange voice whispered words in his ear. The voice gradually grew clearer and more insistent. It filled the fireroom, and then all the rooms of the house. It was a lovely voice, sweet and feminine though coloured with undertones of darkness, passion, and a terrible pride. Only a goddess, he thought, could command such a voice. Only a goddess could speak to him, and sing to him, and recite words of beautiful poetry to him, all at the same time.

Danlo, Danlo, my brave pilot – are you ready?

Danlo stood holding his ears, but still he could hear the Entity’s voice. In acceptance of Her considerable powers, he dropped his hands away from his head and smiled. ‘I … will be tested now, yes?’

Oh, my beautiful man – yes, yes, yes, yes! Go down to the beach where the Cathedral Rock rises from the sea. You must go out toward this rock now; you know the way.

Indeed, Danlo did know the way. Although he had not yet named the offshore rocks visible from the house, there was one rock that pushed straight up out of the water like a cathedral’s spire, a great shining needle of basalt speckled white with the gulls and other birds who nested there. Some days earlier he had tried to climb the cracked face of this rock, only to slip and fall and plunge thirty feet downward into cold, killing sea. He had been lucky not to break his back or drown in the fierce riptide. As it was, the shock of the icy water had nearly stopped his heart; it was only with great difficulty that he had managed to swim to shore. He could not guess why the Entity wanted him to return to this rock. Perhaps She would require him to climb it once more. And so, pausing only to gulp a mouthful of hot tea, he hurried to dress himself in his boots, his kamelaika and his rain robe. He vowed that if he must climb this treacherous rock again, he would not slip. And then, because he had fallen into the strange self-consciousness of remembrance, he smiled and prayed to the spirit of rocks and went down to the sea.

He made his way over the dunes and the hardpack where the sandpipers hopped along singing their high, squeaky chirrups. At the water’s edge he stood in the wet sand and looked out at this so-called Cathedral Rock rising up before him. He saw immediately that he would have little trouble hiking out to it. At low tide the sea pulled back its blankets of water to uncover a bed of rocks: twelve large, flat-topped rocks leading like a path from the shore out into the ocean’s shallows. The tide was now at its lowest, and the rocks were shagged with red and green seaweeds, a living carpet rippling in the wind. Along the sides of the rocks and in the tidepools between them were twenty types of seaweed, the kelps and red-purple Iavers, and a species called desmarestia that used poison to ward off predators. Danlo smelled the faint rotten-egg reek of sulphuric acid, salt and bird droppings and the sweet decay of broken clams. In the tidepools before him there were tubeworms and barnacles and mussels, sea-stars and crabs, anemones and urchins and clams filtering the water for the plankton larvae that they like to eat. He took in all this bright, incredible life in a glance. But he was aware of it only dimly because he had eyes only for another bit of life farther out along the rocks. From the beach, almost back at the house when he had first crested the dunes, he had espied an animal lying flat on top of the twelfth rock, the last in the pathway and the one nearest Cathedral Rock. At first he had thought it must be a seal, though a part of him knew immediately that it was not. Now that he stood with the sea almost sucking at his feet, he could see this animal clearly. It was, in truth, a lamb. It had a curly, woolly fur as white as snow. He had never seen a lamb before, in the flesh, but he recognized the species from his history lessons. The lamb was trussed in a kind of golden rope that wound around its body and legs like some great serpent. It was completely helpless, and it could not move. But it could cry out, pitifully, a soft bleating sound almost lost to the roaring of the sea. It was desperately afraid of the strange ancient sea and perhaps of something other. Although the tide was low, it was a day of wind, and the surf raged and churned and broke into white pieces against Cathedral Rock; soon the sea would return to land and drown the lesser rocks in a fathom of water.

Go out to the lamb now, Danlo wi Soli Ringess.

The godvoice was no longer a sweet song in Danlo’s ears. Now it fell down from the sky and thundered over the water. The sound of the wind and the sea was bottomless and vast, but this voice was vaster still.

Go now. Or are you afraid to save the lamb from its terror?

Danlo faced the wind blowing off the sea. Faintly, he smelled the lamb, its soft, woolly scent, and its fear.

Go. go, please go, my wild man. If you would please me, you must go.

Because Danlo’s rain robe was flapping in the wind, he bent low and snapped it tight around his ankles and knees, the better to allow his legs free play for difficult movements. Then he climbed out onto the first of the twelve rocks. Strands of thick, rubbery seaweed crunched and popped and slipped beneath his boots. With a little running jump, he leaped the distance over the tidepool to the second rock, and then to the third, and so on. He had his walking stick for balance against the slippery rocks, and his awe of the ocean for a different kind of balance, inside. The further out he went, the deeper the water grew around the base of the rocks. In little time, running and leaping against the offshore wind, he reached the twelfth rock. Of all the rocks, this was the largest, except for Cathedral Rock itself. It was fifty feet long and twenty feet wide, and it rose up scarcely five feet above the streaming tide. Above the west end of the rock, toward the sea, across a few feet of open space and dark, gurgling water, Cathedral Rock stood like a small mountain. On Danlo’s last visit here, he had leaped this distance onto the face of Cathedral Rock in his vain attempt to climb it. He had made this leap from a low, seaweed-covered shelf at the very edge of the twelfth rock. This shelf was something like a great greenish stair; it was also something like an altar. For on top of the seaweed and the dripping rock the lamb lay. To its left was a pile of driftwood, grey-brown and dry as bone. To the lamb’s right, almost touching its black nose, a dagger gleamed against the rock shelf. It had a long blade of diamond steel and a black shatterwood handle, much like the killing knives that the warrior-poets use. Danlo immediately hated the sight of this dagger and dreaded the implications of its nearness to the helpless lamb.

Go up to the lamb, Danlo wi Soli Ringess.

Out of the wind came a terrible voice, and the wind was this dark, beautiful voice, the sound and soul of a goddess. Danlo moved almost without thinking. It was almost as if the deeps of the ocean were pulling at his muscles. He came up close to the shelf; the lip of it was slightly higher than his waist. The lamb, he saw, was a young male and it was bleating louder now; each time he opened his mouth to cry out, a puff of steam escaped into the cold air. Danlo smelled milk and panic on the lamb’s breath; he was aware of the minty scent of his own. The lamb, sensing Danlo’s nearness, struggled to lift its head up and look at him. But the golden rope encircled him in tight coils, forcing and folding his legs up against his belly. Danlo reached out to touch the lamb’s neck, lacing his fingers through the soft wool covering the arteries of the throat. The lamb bleated at this touch, shuddering and convulsing against his bonds, and he lifted his head to fix Danlo with his bright black eye. He was only a baby, as Danlo was all too aware as he stroked the lamb’s head and felt the tremors of the animal’s bleating deep inside his throat.

Take up the knife in your hand, my sweet, gentle Danlo.

Danlo looked down at the long knife. He looked over to his left at the heap of driftwood and dry pine twigs. And then, for the tenth time, he looked at the lamb. How had these things come to be here, on a natural altar of rock uncovered by the daily motions of the sea? And somehow his house had been stocked with furniture and furs, with fruits and coffee and bread and other foods. Most likely, he thought, the Entity must be interfaced with some sort of robots who could roam the planet’s surface according to Her programs and plans. Above all else a goddess must be able to manipulate the elements of common matter; and so even a goddess the size of a star cluster must have human-sized hands to move sticks of wood and knives and lambs, and other such living things.

Take up the knife in your hand and slay the lamb. You know the way. You must cut open his throat and let his blood run down the rock into the ocean. I am thirsty, and all streams of life must run into me.

Danlo looked down at the knife. In the uneven sunlight, it gleamed like a silver leaf. He marvelled at the perfect symmetry of the blade, the way the two edges curved up long and sharp toward an incredibly fine point. He wanted to reach his hand out and touch this deadly diamond point, but he could not.

Take up the knife, my Warrior-Pilot. You must cut out the lamb’s heart and make me a burnt offering. I am hungry, and all creatures must rush into my fiery jaws like moths into a flame.

Danlo looked long and deeply at this impossible knife. Then from the sky, the late sun broke through the clouds and slanted low over the ocean to fall over the offshore rocks, over Danlo, over the knife. The blade caught the light, and for a moment, it glowed red as if it had just been removed from some hellish forge. Danlo thought that if he touched the knife his skin would sizzle and blacken, and then the terrible fire would leap up his arm and into his flesh, touching every part of him with unutterable pain, consuming him, burning him alive.

Is it your wish to die? All the warriors of life must slay or be slain, and so must you.

Danlo looked down at this lovely knife that he longed to touch but dared not. He looked at the altar, at the trembling lamb, at the Cathedral Rock and the dark ocean beyond. He suddenly realized that he was facing west, and he remembered a piece of knowledge from his childhood. A man, he had been taught, must sleep with his head to the north, piss to the south, and conduct all important ceremonies facing east. But he must die to the west. When his moment came – when it was the right time to die – he must turn his face to the western sky and breathe his last breath. Only then could his anima pass from his lips and rejoin with the wild wind that was the life and breath of the world.

Slay the lamb now or prepare to be slain yourself.

Danlo looked down and down at this warrior’s knife. He could not pick it up. Did the Entity truly believe that he would forsake his vow of ahimsa merely upon the threat of death? In truth, he could not break this deepest promise to himself. He would not. He would stand here upon this naked rock, for a moment or forever, watching the sunlight play like fire over the knife. His life meant everything to him and yet nothing – of what value was life if he must always live in dread of losing it? He would not pick up the knife, he told himself. He would stand here as the wind rose and the dark storm clouds rolled in from the sea. He would wait for the sea itself to rise and drown him in lungfuls of icy salt water, or he would wait for a bolt of lightning to fall down from the sky and burn his bones and brain. Somehow, he supposed, the Entity must command the lightning electrical storms of angry thoughts that flashed through Her dread brain, and so when She had at last grown vengeful and wroth, She would lift Her invisible hand against him and strike him dead.

You are prepared to die, and that is noble. But it is living that is hard – are you prepared to live? If you take up the knife and slay the lamb, I will give you back your life.

As Danlo stared at the knife pointing toward the lamb’s heart, the wind began to rise. Now the clouds were a solid wall of grey blocking out the sun. The air was heavy with moisture and it moved from sea to shore. Soon the sound of the wind intensified into a howl. It tore at the seaweed carpeting the rock; it caught Danlo’s rain robe and whipped his hair wildly about his head. Like a great hand, the wind pushed against the ocean tide, aiding its rush back to the land. The waters around Danlo surged and broke against the rocks. In moments the whole ocean would rise up above the edge of his rock and soak his boots. And then he must either do as the Entity commanded or defy Her with all his will.

There was a woman whom you loved. You think she is lost to you, but nothing is lost. If you slay the lamb and make me a burnt offering, I will give you back the woman you know as Tamara Ten Ashtoreth. Slay the lamb now. If you do, I shall tell you where you may find Tamara and restore her memories.

For the ten thousandth moment of his sojourn upon this rock, Danlo looked down at the knife. He looked at his long, empty right hand. How the Entity moved the world was a mystery that he might never comprehend, but it was an even greater mystery how anything might move anything. He himself wondered how he might move the muscles of his fingers and clasp the haft of a simple knife. Were not his sinews and his bones made of proteins and calcium and the other elements of simple matter? It should be the simplest thing in the universe to move these five aching tendrils of matter attached to his hand. He need only think the thought and exercise a moment of free will. He remembered, then, that his brain was made of matter too, all his thoughts, his memories, his dreams, all the lightning electro-chemical storms of serotonin and adrenalin that fired his blessed neurons. He remembered this simple thing about himself, and the mystery of how matter moved itself was like an endless golden snake, shimmering and coiling onto itself and finally swallowing its own tail.

This is the test of free will, Danlo wi Soli Ringess. What is it that you will?

Danlo looked down at the knife glittering darkly against the blackish seaweed of the rock. He gazed at the handle, the black shatterwood from a kind of tree that had never grown on Old Earth. He gazed and gazed, and suddenly the whole world seemed to be made of nothing but blackness. The black clouds above him threw black shadows over the inky black sea. The barnacles stuck to the rocks were black, and the rocks themselves, and the pieces of driftwood which the churning waters threw against the shore. Black was the colour of a pilot’s kamelaika and the colour of deep space. (And, he remembered, the colour of the centres of his eyes.) There was something about this strange, deep colour that had always attracted him. In blackness there was a purity and depth of passion, both love and hate, and love of hate. Once, he remembered, he had allowed himself to hate all too freely. Once a time, his deepest friend, Hanuman li Tosh, had stolen the memories of the woman whom Danlo had loved. Hanuman had destroyed a part of Tamara’s mind and thus destroyed a truly blessed and marvellous thing. Danlo had hated him for this, and ultimately, it was this wild hatred that he loved so much that had driven Tamara away and caused Danlo to lose her. And now he hated still, only he had nothing but dread of this blackest of emotions. He gazed at the black-handled knife waiting on a black rock, and he remembered that he hated Hanuman li Tosh for inflicting a wound in him that could never be healed. He ground his teeth, and made a fist, and pressed his black pilot’s ring against his aching eye.

Take up the knife, my wounded warrior. I am lonely, and it is only in the pain of all the warriors of the world that I know I am not alone.

One last time, Danlo looked down at the knife. He looked and looked, and then – suddenly, strangely – he began to see himself. He saw himself poised on a slippery rock in the middle of the sea, and it seemed that he must be waiting for something. He watched himself standing helpless over the lamb. His fists were clenched and his eyes were locked, his bottomless dark eyes, all blue-black and full of remembrance like the colours of the sea. And then, at last, he saw himself move to pick up the knife. He could not help himself. Like a robot made of flesh and muscle and blood, he reached out and closed his fingers on the knife’s haft. It was cold and clammy to the touch, though as hard as bone. He saw himself pick up the knife. Because he hated the Entity for tempting him so cruelly, he wanted to grind the diamond point into the rock on which he stood, to thrust down and down straight into the black, beating heart of the world. Because he hated – and hated himself for hating – he wanted to stab the knife into his own throbbing eye, or into his chest, anywhere but into the heart of the terrified lamb. The lamb, he saw, was now looking at the knife in his hand as if he knew what was to come. With a single dark eye, the lamb was looking at him, the bleating lamb, the bleeding lamb – this helpless animal whose fate it was to die in the crimson pulse and spray of his own blood. Nothing could forestall this fate. Danlo knew that the lamb was easy prey for any predator who hunted the beach. Or if he somehow escaped talon and claw, he would starve to death for want of milk. The lamb would surely die, and soon, and so why shouldn’t Danlo ease the pain of his passing with a quick thrust of the knife through the throat? It would be a simple thing to do. In the wildness of his youth, Danlo had hunted and slain a thousand such animals – would it be so great a sin if he broke ahimsa this one time and sacrificed the lamb? What was the death of one doomed animal against his life, against the promise of Tamara being restored to him and a lifetime of love, joy, happiness, and playing with his children by the hearth fires of his home? How, he wondered, in the face of such life-giving possibilities could it be so wrong to kill?

You were made to kill, my tiger, my beautiful, dangerous man. God made the universe, and God made lambs, and you must ask yourself one question above all others: Did She who made the lamb make thee?

Danlo looked down to see himself holding the knife. To see is to be free, he thought. To see that I see. As he looked deeply into himself, he was overcome with a strange sense that he had perfect will over shatterwood and steel, over hate, over pain, over himself. He remembered then why he had taken his vow of ahimsa. In the most fundamental way, his life and the lamb’s were one and the same. He was aware of this unity of their spirits – this awareness was both an affliction and a grace. The lamb was watching him, he saw, bleating and shivering as he locked eyes with Danlo. Killing the lamb would be like killing himself, and he was very aware that such a self-murder was the one sin that life must never commit. To kill the lamb would be to remove a marvellous thing from life, and more, to inflict great pain and terror. And this he could not do, even though the face and form of his beloved Tamara burned so clearly inside him that he wanted to cry out at the cruelty of the world. He looked at the lamb, and the animal’s wild eye burned like a black coal against the whiteness of his wool. In remembrance of the fierce will to life with which he and all things had been born – and in relief at freeing himself from the Entity’s terrible temptation – he began to laugh, softly, grimly, wildly. Anyone would have thought him mad, standing on a half-drowned rock, laughing and weeping into the wind, but the only witnesses to this sudden outpouring of emotion were the gulls and the crabs and the lamb himself. For a long time Danlo remained nearly motionless laughing with a wild joy as he looked at the lamb. Then the sea came crashing over the rock in a surge of water and salty spray. The great wave soaked his boots and beat against his legs and belly; the shock of the icy water stole his breath away and nearly knocked him from his feet. As the wave pulled back into the ocean, he rushed forward toward the lamb. He held the knife tightly so that the dripping haft would not slip in his hand. Quickly, he slashed out with the knife. In a moment of pure free will, he sawed the rope binding the terrified animal. This done, he stood away from the altar, raised back his arm, and cast the knife spinning far out into the sea. Instantly it sank beneath the black waves. And then Danlo looked up past Cathedral Rock at the blackened sky, waiting for the lightning, waiting for the sound of thunder.

You have made your choice, Danlo wi Soli Ringess.

Another wave, a smaller wave, broke across Danlo’s legs as he reached out his open hand toward the lamb. It occurred to him that if the goddess should suddenly strike him dead, here, now, then the lamb would still die upon this rock, or die drowning as the dark suck of the ocean’s riptide pulled it beneath the waves out to sea.

You have chosen life, and so you have passed the first test.

The lamb struggled to his feet, bleating and shuddering and pushing his nose at Danlo. He stood upon his four trembling legs, obviously terrified to jump down into the rising water. Danlo was all too ready to lead the lamb back to the safety of the beach, but he waited there a moment longer than necessary because he could scarcely believe the great booming words that fell from the sky.

I have said that this was the test of free will. If you hadn’t freely affirmed your will to ahimsa and cut loose the lamb, then I would have had to slay you for lack of faithfulness to yourself.

Once, when Danlo was a journeyman at Resa, the pilots’ college, he had heard that the Solid State Entity was the most capricious of all the gods and goddesses. The Entity, someone had said, liked to play, and now he saw that this was so. But it was cruel to play with others’ lives, especially the life of an innocent lamb. Because Danlo thought that he had finished with the Entity’s games, he bent over to coil up the golden rope lying severed and twisted against the soaking rock. He took up the rope in his hand, and then he reached out to coax the lamb closer to him.

You are free to save the animal, if you can, my warrior. You are free to save yourself, if that is your will.

Danlo reached out to touch the lamb’s nose and eyes, to stroke the scratchy wet wool of his head. Curiously, the lamb allowed himself to be touched. He bleated mournfully and pressed up close to Danlo. It was no trouble for Danlo to wrap his arm around the lamb’s shoulders and chest and pick him up. The animal was almost as light as a baby. With the lamb tucked beneath one arm and his walking stick dangling from his opposite hand, he made his way across the rock in the direction of the beach.

It was nearly dark now, and the sky was shrouded over with the darkest of clouds. He felt the gravity of this Earth pulling heavily at his legs, pulling at his memories, perhaps even pulling at the sky. On the horizon, far out over the black sea, bolts of lightning lit up the sky and streaked down over the water like great glowing snakes dancing from heaven to earth. The whole beach fell dark and electric with purpose, as if the birds and the rocks and the dune grasses were awaiting a storm. Danlo smelled burnt air and the thrilling tang of the sea. Certainly, he thought, it was no time for standing beneath trees or dallying upon a wave-drenched rock. Although there was as yet no rain, there was much wind and water, which made the footing quite treacherous. In his first rush back to the beach, another wave washed over him, and he slipped on the wet seaweed; it was only his stick and his sense of balance that kept him from being swept off the rock. Encumbered as he was, his leaping along the pathway of the twelve rocks back to the beach required all his strength and grace. All the while, the lamb shuddered in his arm. Twice, he convulsed in a blind, instinctive struggle to escape. Danlo had to clasp him close, chest pressing against chest so that he could feel the lamb’s heart beating against his own.

In the falling darkness it was hard to see the cracks and undulations of the twelve rocks and harder still to hear, for the wind blew fiercely, and the rhythmic thunder of the waves was like a waterfall in his ears. And farther out, the long, dark roar of the sea drowned out the lesser sounds: the harsh cry of the gulls, the lamb’s insistent bleating, the distant song of the whales, the mysticeti and belugas and the killers who must swim somewhere among cold, endless waves.

With every step Danlo took along this natural jetty of rocks, the lamb bleated louder and louder as if he could hardly wait to feel the sand beneath his cloven hooves and bound up the beach toward the safety of the dunes.

When they finally jumped down from the last rock and stood on the hardpack by the water’s edge, Danlo decided that he couldn’t let the lamb run free after all. Instead he twisted the golden rope between his fingers and fashioned a noose which he slipped over the lamb’s head. Using the rope as a lead, he led the lamb up the beach. A quarter of a mile away, his lightship was like a black diamond needle gleaming darkly against the soft dunes. And beyond his ship, where the headland rose above the beach and the dunes gave way to the deep green forest, was his little house. In the gloom of the twilight, he could just make out its clean, stark lines. He had a vague, half-formed notion of sheltering the lamb in the house’s kitchen, at least for the night. He would feed the lamb soft cheeses and cream, and then, perhaps, in the morning he would go into the forest to look for the lamb’s flock. He would return the lamb to his mother and save him from the fate that the Entity had planned for him. This was his plan, his pride, his will to affirm the life of a single animal pulling at the golden rope in his hand and bouncing happily along by his side.

It was in among the grasses of the low dunes, with the house so close he might have thrown a rock at it, that they came upon the tiger. Or rather, the tiger came upon them. One moment Danlo and the lamb were alone together with the rippling grass and the wind-packed sand, and a moment later, upon a little ridge between them and the house, the tiger suddenly appeared. Danlo was the first to see it. His eyes were better than those of the lamb, although his sense of smell was not as keen; but with the wind blowing so fiercely from the sea, neither he nor the lamb could have caught the tiger’s scent. And so Danlo had a moment to look at the tiger before the lamb noticed what he was looking at and bleated out in panic. The tiger crouched belly low to the sand, the long tail held straight out and switching back and forth through the sparse grass. She – Danlo immediately sensed that she was female – fixed her great glowing eyes on them, watching and waiting. And Danlo looked at her. Although he knew better than to stare at a big cat (or any predator), for a single moment he stared. Something about this particular tiger compelled his attention. She was a beautiful beast some nine feet in length and twice or thrice his own weight. In the tense way that she waited she seemed almost afraid of him, yet she was not at all eye-shy for she continued to stare, never breaking the electric connection of their eyes. He decided immediately that there was something elemental and electric about all tigers, as if their powerful, trembling bodies were incarnations of lightning into living flesh. In the tiger’s lovely symmetry and bright eternal stare there blazed all the energies of the universe. The tiger’s face was a glory of darkness and light: the broken circles of black and burning white that exploded out from a bright orange point centred between her brilliant eyes. For an endless moment, Danlo stared, falling drunk with the intoxicating fire of the tiger’s eyelight. Then something strange began to happen to him. He began to see himself through the tiger’s eyes. He looked deeply into the twin yellow mirrors glowing out of the twilight, and he saw himself as a strange and fearful animal. Strange because he stood on two legs and brandished a long black stick, and fearful because he stood much taller than the tiger, and more, because his dark blue eyes faced forward in a brilliant and dangerous gaze of his own. He, like all men, had the eyes of a predator, and through the coolness of the early evening air, the tiger saw this immediately. The tiger saw something else. Although it was unlikely that she had ever encountered a man before, she must have looked within her own racial memories and relived the ancient enmity between feline and man. She must have remembered that although man killed lambs and other animals for food, once a time, it was the lions and tigers and other big cats of Afarique who had hunted man.

Danlo remembered this too. He remembered it with a gasp of cold air and the hot shock of adrenalin and the sudden quick pounding of his heart; in a stream of dark and bloody images called up from his deepest memories he remembered the essential paradox of his kind: that man was a predatory animal who had once been mostly prey. He remembered that he should have feared this tiger. On the burning veldts of Afarique, two million years ago in the primeval home of man, the fiercest predators on the planet had been everywhere: in the tall grasses and in caves and hiding behind the swaying acacia trees, always watching, always waiting. The tiger was the true Beast of humankind, the avatar of Hell out of the dark past. The tiger was a killer – but also something else. For it was the big cats, in part, that had driven human beings to evolve. For millions of years the tiger and the leopard had chased men and women across the grasslands, forcing them to stand upright and pick up sticks and stones as weapons of self-defence. Out of fear of darkness and bright pointed teeth, man had found fire and had made blazing torches with which to frighten these meat-eaters and keep them at bay. The constant evolutionary pressure to escape nature and its most powerful beasts had driven human beings to create spears and baby slings and stone huts, ultimately to build cities and lightships and sail out to the stars. Looking out across the darkening dunes at the tiger, Danlo marvelled at the courage with which his far fathers and mothers and all his ancestors had come down from the trees and faced the big cats, thus turning the possibility of extinction into evolution, death into life. In the short moment that he met the tiger eye to eye – while the innocent lamb still pawed the sand and trotted along unaware – Danlo saw the entire history of the human race unfold. And the deeper he looked into the black, bloody pools of the past, and into himself, the more clearly he saw the tiger’s burning face staring back at him. The darkness falling slowly over the beach did little to obliterate this vision. As the light failed over the dunes and the dark forest disappeared into the night, still he could see the tiger watching him. He remembered how tigers loved the night, how they loved to roam and roar and hunt at night. It came to him suddenly that in this love of walking alone beneath the stars, tigers were the true architects of man’s fear of the dark. All history, all philosophy had sprung from this fear. Darkness, for man, was death – whether the endless death of being enclosed in a wood coffin or the sudden death that came flashing out of the night in an explosion of hot breath and tearing claws. Man had always dreaded darkness and thus worshipped light; the ancient philosophers of the human race, in their beards and their fear, had made a war between light and dark, good and evil, spirit and matter, life and death. This urge to separate form from function, the sacred from the profane, was the fundamental philosophical mistake of mankind. Human beings, in their mathematics and their lightships, in their evolution into the universe, had only carried this mistake across the stars. And human beings, though they might explode the stars themselves into billions of brilliant supernovas, would never vanquish darkness or the terrible creations hidden in the folds of the night.

As Danlo stared forever at the tiger across a hundred feet of darkening beach, these thoughts blazed through his brain. The wind roared in from the sea, carrying in the sound of thunder, and he fell into a keen awareness of the night-time world. Above him were black clouds, black sky, the omnipresent blackness of the universe. Danlo realized then how much he had always hated (and loved) dark places. Yet strangely, like any man, he had always felt the urge to open the door to the darkest of rooms and see what lay inside. Or open the door to his house and see what is outside, in the night. And here, now, on this desolate beach, there was only a tiger. He looked at the tiger’s bright golden eyes blazing out of the darkness, and he remembered a line from the Second Hymn to the Night: You are the messenger who opens mysteries that unfold forever. He knew that the tiger would always be a mystery to him, as he was to himself.

And now the night was opening this mystery, beginning to reveal it in all its glory. Now, over the ocean, the storm was beginning to break. In sudden crackling bolts appearing out of nowhere, lightning played in the sky, connecting heaven to earth. It illuminated the beach in flashes of light. For a moment, the tiger and the lamb and the other features of the world were revealed in all their splendour, and then the dunes and the rocks and the sand vanished back into the night. During this brief moment of illumination, while tiger’s orange and black stripes burned with a strange numinous fire, reality was charged with such a terrible intensity that it seemed almost too real. With each stroke of lightning there was a moment of dazzle and then darkness. Danlo had a deep sense of knowing that there was something behind this darkness, all vivid and white like the lamb’s snowy fleece, but he could not quite see it. The lightning broke upon the beach, suddenly, mysteriously, and he marvelled at the way light came from darkness and darkness devoured light. In one blinding moment he saw that although tigers were truly creatures of darkness, this lovely tiger who waited for him on the darkling dunes had everything to teach him about the true nature of light.

When the tiger finally sprang, it was as if she had been waiting a million years to be released from a secret and unbearable tension. She flew forward in an explosion of colours, all orange-gold and black and streaked with white, and attacked in a series of violent leaps that carried her hurtling across the beach. Her paws hardly touched the sand. Although Danlo had had almost forever to decide how to meet the tiger, when she finally struck he had little time to move. In truth, he had nowhere to run, for there was nothing but grass and sand all around him, and even if the tiger hadn’t blocked the way to the house, he could never have reached its safety before the tiger reached him. Still, he thought that he should try to run, if only to lead the tiger away from the lamb. He should save the lamb; if he and the lamb ran in opposite directions, then the tiger might catch only one of them in her claws. It didn’t occur to him, at first, that the lamb was the tiger’s intended prey, not he. But when he decided to drop the rope and the lamb screamed out in terror, he knew. The tiger, in her astonishing dash across the beach, was no longer looking at Danlo. Her golden eyes were now fixed straight ahead on the lamb. Danlo immediately moved to place his body in front of the lamb, but it ruined his plan by springing suddenly to the left and thus entangling Danlo’s legs in the rope. His feet slipped on the soft sand even as the tiger bolted toward them. For a moment, as he stared at the tiger’s wild eyes and the powerful, rippling muscles that flowed like rivers beneath her fur, he remembered how, as a boy, he had once stood beneath an icy forest and watched as his near-father, the great Wemilo, had slain a snow tiger with nothing more than a simple spear. He remembered this clearly: the silence of the winter woods, the clean white snow, the tremendous power of Wemilo’s thrust as his spear found the heart place and let loose a waterfall of blood. But he had no knife, no spear, no time. In a second, the tiger would be upon him. There was nothing he could do. All his instincts cried out for him to devise some clever plan to flee or fight, and it nearly killed him to wait there in the sand as helpless as a frozen snow hare. But then it came to him that there was always a time to just stand and die, and he was afraid that his time had finally come. For surely the tiger would kill him in her lust to get at the lamb. He thought to raise his walking stick as a last defence, but against the power and ferocity of her attack, it would be worse than useless. The most he might accomplish – and only with perfect timing – would be to ram the sandy point of the stick into her lovely yellow eye. But this would not discourage her; it would only enrage her and cause her to fall into a killing frenzy, thereby dooming both him and the lamb. And more, such an injury could blind the tiger on one side. The wound might bleed and fester; ultimately, it might cause the tiger to sicken and die. He knew that he could never do such a deed. He remembered his vow of ahimsa then, and he realized that even if he had hated the tiger, he could never have harmed such a marvellous beast.

The tiger sprang through the air directly at the lamb, and he loved her: her rare grace, her vitality, her wild joy at following the terrible angels of her nature. The tiger, in her moment of killing, was nothing but energy and joy, animajii – the joy of life, the joy of death.

Even the lamb, he saw, knew a kind of joy. Or rather, the lamb was wholly alive with the utter terror to save his own life, and this sudden nearness of mortality was really the left hand of joy. As the tiger fell upon him, the lamb screamed and shuddered and jerked in the direction of the ocean in his blind urge to run away. Danlo, who had finally fought free of the rope binding them, tried to come to his aid. He too leaped toward the lamb. But the explosive force of the tiger’s strike knocked him aside as he collided with her. There was a shock of bunched muscles and bone, a rage of orange and black fur and slashing claws. Danlo smelled the tiger’s fermy cat scent and caught wind of her hot bloody breath. Her glorious face, all open with fury and gleaming white fangs, flashed in front of his. The lamb screamed and screamed and tried to leap away dragging the golden rope behind him. Then the tiger sank her claws into his side as she pulled him to the ground, and the terrible screaming suddenly stopped. The lamb fell into a glassy-eyed motionlessness, offering no more resistance. Again, Danlo leaped at the tiger, grabbing the loose skin at the back of her neck and trying to pull her off the lamb. He sank his fingers into her thick fur, and he pulled and pulled. The tiger’s deep-throated growls vibrated through her chest; Danlo felt the great power that vibrated through her entire body. Through the brilliance of another flash of lightning, he saw the tiger open her jaws to bite the lamb’s neck. He remembered then how Wemilo had once been mauled by a snow tiger. Once in deep winter, Danlo’s found-father, Haidar, had brought Wemilo all broken and bloody back to their cave, and Wemilo had told an incredible story. Even as Haidar had held a burning brand to Wemilo’s face to cauterize his wounds, this great hunter had claimed that at the supreme moment of his ordeal, with the tiger tearing at him, he had felt neither fear nor pain. He said that he had fallen into a kind of dreaminess in which he was aware of the tiger biting open his shoulder but did not really care. The laying bare of his shoulder bones, he said, seemed almost as if it were happening to someone other than himself. And now, above the beach as the lightning flashed, as Danlo pulled vainly at two handfuls of quivering flesh, this tiger was about to make her kill, and Danlo could only hope that the lamb had entered into the final dreamtime before death. All his life he had wondered what lay beyond the threshold of that particular doorway. Perhaps there was joy in being released from life, a deep and brilliant joy that lasted forever. Perhaps there was only blackness, nothingness, neverness. Danlo wondered if he himself might be very close to following the lamb upon her journey to the other side, and then at last the tiger struck down with her long fangs. Her teeth were like knives which she used with great precision. She bit through the lamb’s neck, tearing open the throat with such force that Danlo felt the shock of tooth upon bone run down the whole length of the tiger’s body. Blood sprayed over the tiger’s face and chest, and over Danlo who still clung desperately to the back of the tiger’s neck. The lamb lay crushed beneath the tiger’s paws, and his dark eye was lightless as a stone. Danlo should have let go then and tried to run, but the tiger suddenly jumped up from her kill and whirled about. With a single great convulsion of muscles, she whirled and rolled and roared, trying to shake Danlo loose. She drove him straight back to the sand. The force of their fall knocked his breath away. If the sand hadn’t been so soft, the tiger might have broken his back. For a moment, Danlo was pinned beneath her. The tiger’s arching spine drove back into his belly and chest nearly crushing him. There was blood and fur in his mouth, and he could feel the tiger’s powerful rumblings vibrate deeply in his own throat. And all the while the tiger roared and snapped her jaws and clawed the air. She continued to roll, spinning along the beach until she pulled Danlo off and found her feet. She crouched in the sand scarce three feet away. Her breath fell over Danlo’s face. He, too, was now crouching, up on one knee as he held the bruised ribs above his belly and gasped for air. He waited for the tiger to spring. But the tiger did not move. During a flash of lightning, she found his eyes and stared at him. It lasted only a moment, this intense, knowing look, but in that time something passed between them. She stared at him, strangely, deeply, and at last she found her fear of the mysterious fire that she saw blazing in Danlo’s eyes. She turned her head away from him, then. She stood and turned back toward the lamb who lay crumpled in the sand. With her teeth, she took him up by his broken neck as gently as she might have carried one of her cubs. The lamb dangled from her teeth, swaying in the wind. Without a backward glance, she padded off up the dunes toward the dark forest beyond, and then she was gone.

For a while Danlo knelt on the beach and watched the heavens. He faced west, looking up at the black sky, listening to the wind and decided to say a prayer for the lamb’s spirit. But he did not know the true name of the lamb; on the islands west of Neverness there are no lambs, nor any animals very much like lambs. Without a true name to tell the world, Danlo could not pray properly, but he could still pray, and so he said, ‘Ki anima pela makala mi alasharia la shantih’. He touched his fingers to his lips, then. His hands were wet with the lamb’s fresh blood, and he opened his mouth to touch his tongue. It had been a long time since he had tasted the blood of an animal. The lamb’s blood was warm and sweet, full of life. Danlo swallowed this dark, red elixir, and thanked the lamb for his life, for giving him his blessed life. Soon after this it began to rain. The sky finally opened and founts of water fell down upon the beach in endless waves. Danlo turned his face to the sky, letting this fierce cold rain wash the blood from his lips, from his beard and hair, from his forehead and aching eyes. He scooped up some wet sand and used it to scour the blood off his hands. As lightning flashed all around him and the storm intensified, he watched the lamb’s blood run off him and wash into the earth. He thought the rain would wash the blood through the sand, ultimately down to the sea. He thought that even now the lamb’s spirit had rejoined with the wind blowing out of the west, the wild wind that cried in the sky and circled the world forever.

That night, when Danlo returned to his house, he had dreams. He lay sweating on a soft fur before a blazing fire, and he dreamed that a tall grey man was cutting at his flesh, sculpting his body into some dread new form. There was a knife, and pain and blood. With a sculptor’s art, the tall grey man cut at Danlo’s nerves and twisted his sinews and hammered at the bones around his brain. And when the sculptor was done with this excruciating surgery and Danlo looked into his little silver mirror, he could not quite recognize himself, for he no longer wore the body of a man. All through this terrible dream that wouldn’t end, Danlo stared and stared at the mirror. And always staring back at him, burning brightly with a fearful fire, was the face of a beautiful and blessed tiger.