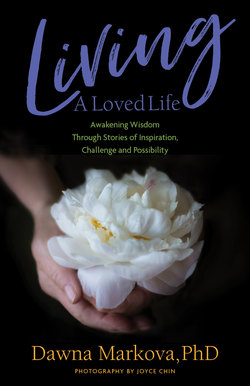

Читать книгу Living A Loved Life - Dawna Markova PhD - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPretending I’m Not Pretending

In high school, I perfected the art of the shrug. The thing I said the most often was, “I’m bored.” I had skipped a grade twice in elementary and middle school, and, at fifteen, the last thing I wanted was to stand out as special in any way. I was a flat-chested senior who still hadn’t gotten her period. I figured out how to dumb myself down by simplifying my vocabulary and putting enough wrong answers on tests so that I could maintain a C average. But I was bored, bored all the way down to my bone marrow. All I wanted was to be left alone under the blankets with a flashlight or in my school locker, reading anything and everything I could find.

I decided my salvation would come in college. My mother and father both thought it was a waste of time, but I convinced them that I’d just be moping around the house and driving them crazy if I didn’t go. They finally agreed, but only if I studied something that could lead to finding a husband: nursing would be best because it would expose me to a lot of doctors. Teaching was second-best, because I’d at least learn how to prepare for motherhood. Morton Barron, my high school counselor, suggested that, since I had a straight C average, the only safe school that I could get into was Syracuse University. I followed his “guidance,” because at least it would take me away from boredom.

Of course, first I had to take the College Board exams. Unfettered by the need to dumb myself down, I surfed right through the waves of questions easily. A few weeks later, Morton Barron called me back into his office to ask how I had managed to cheat on the College Boards. I had no idea what he was talking about, so I just shrugged. He explained that I had earned virtually perfect scores on all the tests and that no girl with a straight C average could do that. He insisted I take them again. A week after I did so, he called me back and said the results were exactly the same. Maybe I hadn’t cheated, he conceded, but it was too late to apply to a better school, perfect scores or not. My mother became concerned that no prince would want a wife who was smarter than he. My father looked around the 721-acre campus of Syracuse with its tens of thousands of diverse students and knew his little princess was going to be lost.

Which I was, of course. Lost, and still bored, bored, bored. In education classes, they taught me how to draw Easter bunnies and put swabs of cotton on their backsides. But in sophomore year, my mind broke open like buds on a spring cherry tree. I didn’t “take” classes, I consumed them: anthropology, biology, cognitive psychology, neurology, philosophy. After three years devouring the undergraduate curriculum, I applied for a grant to an experimental master’s/doctoral program at Columbia. I was admitted. I knew my parents wouldn’t pay for such a “waste of time,” so I got a job taking care of the fifth graders no one else wanted to teach in a Harlem elementary school to pay my tuition.

I didn’t think teaching had anything to do with my Promise. I just assumed it was a way of earning enough money to pursue the questions that nagged me more than my mother. Why couldn’t my father learn to read when he was such a brilliant leader? Why was I so miserable at learning to throw a softball or swim even though I could master Latin with ease? The kids I was teaching were another riddle. They came to school with rat bites on their cheeks, but my grandmother had taught me that each one of them mattered to the world in a very specific way. I assumed they were all riddles. I noticed that Myron did best when he bounced a basketball while saying the alphabet but spaced out when looking at written words on a page. Jason hated phonics, but he could focus his eyes on a whole paragraph, read it silently, and then draw what it was about. Charlene could read only if she was in a rocking chair or pacing around the room.

None of the classes I was taking at Columbia helped me to understand these differences. I was taught how to classify, recognize, and treat pathology. This would have been useful if I wanted to help these kids get sick, go crazy, or grow up dumb, but never once did I ever hear a professor describe what a healthy human mind is, how it learns, or how one mind can communicate effectively with another.

Just as my grandmother had predicted, inspiring life-giving forces were also available to me. In the spring of my last year, I took a course at NYU with a brilliant neuroscientist named E. Roy John. He considered himself a quantitative electroencephalographist. Whatever that was, he reminded me most of a very tall dessert cactus, a night-blooming cereus, that produces immense white blossoms every June. In Roy’s case, the blossoms opened when he placed little electrodes all over a person’s skull and hooked them up to electroencephalographic equipment he had invented. I stood next to him and watched in awe as a child’s brain lit up in its own unique way. He had developed a mechanism to actually watch a human think and learn! I knew that what I was seeing would change the way I thought and taught for the rest of my life.

One by one, I brought the kids from Harlem to the lab and we hooked each one up. I suggested specific things for them to think about. Myron’s brain lit up when he imagined doing kinesthetic activities such as running. It spaced out, however, when he thought about writing or reading. Jason’s brain lit up imagining writing or drawing but spaced out with auditory tasks such as speaking or music. Miranda’s spaced out imagining running or dancing but lit up when she thought about talking or singing. Both Roy and I were stunned. Child after child gave us more corroboration that, although each brain’s structure was similar, each one was energized by a different method of processing information.

One night, while listening to a concert of “Rhapsody in Blue” by George Gershwin, it dawned on me that brains functioned just like musical instruments. Instruments all used vibration to produce sounds, but some did it with wind, some with strings. You played some by bowing strings, others by strumming. What if all human brains produced “thought,” but in different sequences or patterns of visual, auditory, and kinesthetic input to perform the act we call “thinking?” What if knowing which sequence a child innately used would help each of those “difficult, unteachable, disabled” kids in Harlem “play” the music we call learning?

This understanding was more of an uncovering than a discovering. It has continued to fascinate, obsess, and magnetize me for fifty-five years. But I also realized that making sure each child I came in contact with knew specifically how he or she mattered was even more important. I hung a sheet of newsprint for each child I taught on the battered walls of my Harlem classroom and put his or her name at the top. A half hour before the final bell rang each day, I asked them to stand in front of any paper and write one way that particular student had made their day better. By the time the bus arrived, each sheet of newsprint was full. At the end of the school year, I typed up the contents of each child’s newsprint pages. I told them my grandmother’s Promise story, and I then read each of their papers aloud to the whole class.

Three decades later, Charlene somehow found me. She wrote to say that she was the first in her family to graduate both high school and college. Hanging next to her diplomas, she had framed that paper reminding her of the Promise she carried in the world.