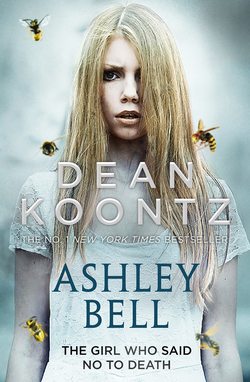

Читать книгу Ashley Bell - Dean Koontz, Dean Koontz - Страница 20

13 Young Again in Grief

ОглавлениеON THE DRIVE HOME FROM THE HOSPITAL, through the alien night, Murph and Nancy shared an awful, solemn silence. The mutual quiet became so oppressive, so suffocating, that several times one or the other tried to slash it away with words, but both were rendered incoherent and emotionally bewildered by the loss that seemed to lie in their future. The unthinkable loss.

With greater success in retail and real estate, they had moved from the bungalow three years earlier, into a two-story pale-yellow stucco house with sleek modern lines. They still lived in that part of Corona del Mar known as the Village, no longer three blocks short of the Pacific but only one and a half. From the roof deck, from one upstairs room, and from the front terrace on the ground floor, they had an angled view of the ocean that lay beyond the end of the east-west street.

Murph had been proud that two surf rats—as he still thought of himself and Nancy—could remain in touch with their beach roots and nevertheless earn a major piece of the California dream. That night, however, the house meant nothing to him, and in fact it seemed cold and unfamiliar, as if by mistake they had let themselves into a residence owned by strangers.

He and Nancy had always been understanding of each other, always available to each other, uncannily in sync in all circumstances. He assumed they would sit together at the kitchen table, the lights low, maybe in candlelight, and together work their way through the horror and the pain of what had befallen them.

As it turned out, neither of them was ready for that. As if the shock, still building force hour by hour, had not only cast them off their moorings, but also had washed them far back in time, both chose to revert to the coping mechanisms of their youth. No doubt they would come together soon, but not yet.

Nancy went into the ground-floor powder bath, snared the box of Kleenex from the counter, dropped the lid of the toilet with a bang, and sat down as from her came the most wretched sounds of grief that Murphy had ever heard issue from anyone. When he spoke to her and tried to enter the half bath, she said, “No, not now, nooo,” and pushed the door shut in his face.

Feeling helpless, useless, he stood listening to her despairing sobs, to the thin shrill animal sounds of utter desolation that tore from her between desperate ragged breaths. She sounded like a child, racked as much by fear as by misery. Her heartbreak sharpened his own until he could not stand to listen to her a moment longer.

If Nancy reverted to childhood in her grief, Murphy fell back into the angry rebellion of adolescence. He took a six-pack of cold beer from the refrigerator and carried it up to the roof deck. He wanted to punch someone, anyone, just punch and punch until he was exhausted and his knuckles were swollen. He wanted someone to pay—to suffer and be chastened—for the unfairness of Bibi’s cancer. But there was no one to hold responsible, nor anyone to comfort him, not in a world where what will be will be. Instead, he sat in a redwood lounge chair, opened the first can of Budweiser, and chugged it as he stared over his neighbors’ roofs, over the few lights along the last width of the bluff, stared out into the vast night sea, which lay black under a moonless sky, black under a higher blackness salted with icy stars, its presence confirmed only by the rhythmic rumble of the breakers punishing the shore. Halfway through the second beer, he began to cry. Weeping only fueled his anger, and the angrier he became, the harder he wept.

He wished they had gotten another dog after Olaf died. Dogs needed no words to console you. Dogs were the ultimate practitioners of the therapy of touch. Dogs knew and accepted the hard realities of life that human beings could not acknowledge until those obvious truths were exhaustively described with words, and even then there was often more bitter acknowledgment than humble acceptance.

Dogless, perhaps soon to be childless, after only two beers, Murphy felt lost. If he had tried to go downstairs to his wife at that moment, he would not have been surprised if he’d been unable to find his way off the roof deck.

With a crisp metallic sound, the ring-pull peeled open the third can.