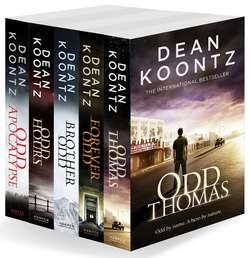

Читать книгу Odd Thomas Series Books 1-5 - Dean Koontz, Dean Koontz - Страница 42

CHAPTER 33

ОглавлениеAFTER CLOSING THE LEVOLOR AT THE window, leaving the lights off, I went to the bureau, which was near the bed. In this one room, everything could be found near the bed, including the sofa and the microwave.

In the bottom drawer of the bureau I kept my only spare set of bed linens. Under the pillowcases, I found the neatly pressed and folded top sheet.

Although without a doubt the situation warranted the sacrifice of good bedclothes, I regretted having to give up that sheet. Well-made cotton bedding is not cheap, and I am mildly allergic to many of the synthetic fabrics commonly used for such items.

In the bathroom, I opened the sheet on the floor.

Being dead and therefore indifferent to my problems, Robertson could not be expected to make my job easier; however, I was surprised when he resisted being hauled out of the tub. This wasn’t the active counterforce of conscious opposition, but the passive resistance of rigor mortis.

He proved to be as stiff and difficult to manage as a pile of boards nailed together at odd angles.

Reluctantly, I put a hand to his face. He felt colder than I’d expected that he would.

Perhaps adjustments needed to be made in my understanding of the events of the previous evening. Unthinkingly, I had made certain assumptions that Robertson’s condition didn’t support.

To learn the truth, I had to examine him further. Because he had been lying facedown in the tub when I’d found him, before I’d turned him over, I now unbuttoned his shirt.

This task filled me with loathing and repugnance, which I had anticipated, but I wasn’t prepared for the abhorrent sense of intimacy that spawned a slithering nausea.

My fingers were damp with sweat. The pearlized buttons proved slippery.

I glanced at Robertson’s face, certain that his gaze would have refocused from some otherworldly sight to my fumbling hands. Of course his expression of shock and terror had not changed, and he continued staring at something beyond the veil that separates this world and the next.

His lips were slightly parted, as though with his last breath he had greeted Death or had spoken an unanswered plea.

Looking at his face had only made my heebie-jeebies worse. When I lowered my head, I imagined that his eyes tracked the shifting of my attention to the stubborn buttons. If I had felt a fetid breath exhaled against my brow, I might have screamed, but I wouldn’t have been surprised.

No corpse had ever creeped me out as badly as this one. For the most part, the deceased with whom I interact are apparitions, and I am spared too much familiarity with the messy biological aspect of death.

In this instance, I was troubled less by the scents and sights of early-stage corruption than by the physical peculiarities of the dead man, mostly that spongy fungoid quality that had marked him in life, but also by his extraordinary fascination—as revealed in his files—for torture, brutal murder, dismemberment, decapitation, and cannibalism.

I undid the final button. I folded back his shirt.

Because he wore no undershirt, I saw the advanced lividity at once. After death, blood settles through the tissues to the lowest points of the body, giving those areas a badly bruised appearance. Robertson’s flabby chest and sagging belly were mottled, dark, and repulsive.

The coolness of his skin, the rigor mortis, and the advanced lividity suggested that he had not died within the past hour or two but much earlier. The warmth of my apartment would have accelerated the deterioration of the corpse, but not to this extent.

Very likely, in St. Bart’s cemetery, when Robertson had given me the finger as I’d looked down on him from the bell tower, he had not been a living man but an apparition.

I tried to recall if Stormy had seen him. She had been stooping to retrieve the cheese and crackers from the picnic hamper. I had accidentally knocked them from her hands, spilling them across the catwalk ...

No. She hadn’t seen Robertson. By the time she got up and leaned against the parapet to look down at the graveyard, he had gone.

Moments later, when I opened the front door of the church and encountered Robertson ascending the steps, Stormy had been behind me. I had let the door fall shut and had hustled her out of the narthex, into the nave, toward the front of the church.

Before going to St. Bart’s, I’d seen Robertson twice at Little Ozzie’s place in Jack Flats. The first time, he had been standing on the public sidewalk in front of the house, later in the backyard.

In neither instance had Ozzie been in a position to confirm that this visitor was a real, live person.

From his perch on the windowsill, Terrible Chester had seen the man at the front fence and had strongly reacted to him. But this did not mean that Robertson had been there in the flesh.

On many occasions, I have witnessed dogs and cats responding to the presence of spirits—though they don’t see bodachs. Usually animals do not react in any dramatic fashion, only subtly; they seem to be totally cool with ghosts.

Terrible Chester’s hostility was probably a reaction not to the fact that Robertson was an apparition but to the man’s abiding aura of evil, which characterized him both in life and death.

The evidence suggested that the last time I’d seen Robertson alive had been when he’d left his house in Camp’s End, just before I had loided the lock, gone inside, and found the black room.

He had haunted me since, and angrily. As though he blamed me for his death.

Although he’d been murdered in my apartment, he must know that I hadn’t pulled the trigger. Facing his killer, he’d been shot from a distance of no more than a few inches.

What he and his killer had been doing in my apartment, I could not imagine. I needed more time and calmer circumstances to think.

You might expect that his pissed-off spirit would have lurked in my bathroom or kitchenette, waiting for me to come home, eager to threaten and harass me as he had done at the church. You would be wrong because you forget that these restless souls who linger in this world do so because they cannot accept the truth of their deaths.

In my considerable experience, the last thing they want to do is hang around their dead bodies. Nothing is a more poignant reminder of one’s demise than one’s oozing carcass.

In the presence of their own lifeless flesh, the spirits feel more sharply the urge to be done with this world and to move on to the next, a compulsion that they are determined to resist. Robertson might visit the place of his death eventually, but not until his body had been removed and every smear of blood had been scrubbed away.

That suited me fine. I didn’t need all the hullabaloo associated with a visitation by an angry spirit.

The vandalism in St. Bart’s sacristy had not been the work of a living man. That destruction had been wrought by a malevolent and infuriated ghost in full poltergeist mode.

In the past, I’d lost a new music system, a lamp, a clock radio, a handsome bar stool, and several plates during a tantrum by such a one. A short-order cook can’t afford to play host to their kind.

This is one reason why my furnishings are thrift-shop rejects. The less that I have, the less I can lose.

Anyway, I looked at the lividity in Robertson’s flabby chest and sagging belly, quickly made the aforementioned deductions, and tried to button his shirt without looking directly at his bullet wound. Morbid interest got the best of me.

In the soft and livid chest, the hole was small but ragged, wet,—and strange in some way that I didn’t immediately grasp and that I didn’t want to contemplate further.

The nausea crawling the walls of my stomach slithered faster, faster. I felt as if I were four years old again, with a dangerously virulent case of the flu, feverish and weak, staring down the barrel of my own mortality.

Because I had enough of a mess to clean up without reenacting Elvis’s historic last spew, I clenched my teeth, repressed my gorge, and finished buttoning the shirt.

Although I surely know more than the average citizen about how to read the condition of a corpse, I am not a specialist in forensic medicine. I couldn’t accurately determine, to the half hour, the exact time of Robertson’s death.

Logic put it between 5:30 and 7:45. During that period, I had searched his Camp’s End house and explored the black room, had driven Elvis to the chief’s barbecue and subsequently to the Baptist church, and had cruised alone to Little Ozzie’s house.

Chief Porter and his guests could verify my whereabouts for part of that time, but no court would look favorably on the claim that the ghost of Elvis could provide me with an alibi for another portion of it.

The extent of my vulnerability became clearer by the moment, and I knew that time was running out. When a knock at the door eventually came, it would most likely be the police, sent here by an anonymous tip.