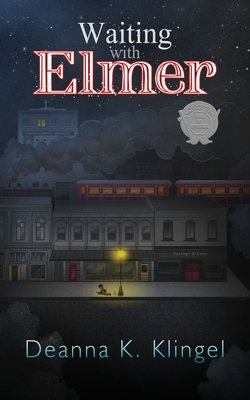

Читать книгу Waiting with Elmer - Deanna K. Klingel - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter Five

They left the park and headed up the sidewalk toward the drug store. Next to the drug store was a door Willy hadn’t noticed before. The narrow door and the ramp were painted yellow. They stepped inside into a cloud of antiseptic odors. Elmer motioned for Willy to sit down on the leather couch that had a torn hole where cotton stuffing tried to escape on a bent spring. He sat down, looked at the floor, and counted the black and white shiny tile squares. A tall lady with pink cheeks and a white cap on her head stepped through the door on silent white shoes. Willy gulped.

She’s gonna kick me out of here.

“This your friend, Elmer?”

“It is, Mary, it is. May I present Mr. Willy Sykes?” The lady held her hand out to Willy. He quickly wiped his hand off on his pants, and, disbelieving, he gave her his hand, which she pumped heartily.

“Nice to meet you, Willy. Come on in.” Willy looked at Elmer who nodded encouragement. Mary took Willy by the elbow and directed him into a small room. Everything in it was disinfected white enamel.

“Drop your pants, Willy,” Mary said cheerfully.

Willy shot her a look of alarm. “Oh, for Petey’s sake, don’t be a baby.” Willy slowly lowered his pants while keeping an eye on Mary and the long needle she was tapping. In one smooth, swift move, she turned Willy around, yanked his drawers, and poked the needle into his hip. Willy choked on his yelp. She slapped on a piece of cotton, stuck it with tape, chuckled, and said, “Off with you now. Do good in school and make Elmer proud of you.” With that she slipped out the door.

Willy let go his pants and they sagged to the floor. He rubbed the cotton, recovered, and restored his dignity.

“Next stop, the drug store,” said Elmer. “They have the book lists there and used textbooks. What class you in, Willy?”

“I don’t know. Well, I’m not sure. My last birthday I remember having, I was ten. That’s been a while, though. My Grandma, she… it’s been… a while ago.” Elmer glimpsed the ghostly shadow that passed over Willy’s face like a wisp of a haint.

“I went to school, but in lots of different towns, so I don’t know what grade I’d be if I stayed anywhere. You think that means I can’t go?”

“Absolutely not! We’ll get it sorted out soon enough. The teacher can figure out where you should be. You don’t worry about it; you just do the best you can.” They turned up the blue ramp at the drug store.

By the time they returned to the Union Mission, Elmer’s platform was piled with paper bags and Willy carried an armload of packages wrapped in brown paper and tied with string. The men at the mission gathered around the big table to see all the packages opened and admired.

Men in rags proclaimed Willy’s new pair of school pants the best-looking knickers they ever saw, and the shirts, too, all had matching buttons. Zipper, who was always barefoot, admired Willy’s almost-new shoes.

“Shiny,” he said. “Slick shoes.” Zipper’s bare feet tapped a little dance beneath the table.

Drum rubbed the new geography book with his fingers and said what fine pictures were in it.

“I’ll read it to you, if you want me to, Drum,” Willy said.

“Oh, that’s real nice, Willy. I’ll take you up on that.”

Rake told Willy to run back to town and ask Mr. Okei, the grocer, for an empty orange crate.

“It’s time you had your own furniture,” he said.

Willy helped clean up after their supper. He put his tin plate into the sink and wiped the oil cloth table covering with a wet sponge. Rake whispered to him that since he had someplace to be every morning now, he’d be allowed to use the bathtub whenever he needed. Rake handed him a bar of soap for his own personal use.

Willy placed the orange crate next to his bed. He stacked his books on its shelf. On the bottom he put his tablets, pencils, and lunch box. He placed his toothbrush, a tin of Mrs. Lyons Tooth Powder, a metal comb, and the bar of lye soap, all in a cigar box one of the men handed him and sat it all on the top of the orange crate. Elmer gave him a large canvas bag from the army surplus store. He put his new clothes in it and hung it on the end of the bed. He had his very own space. He dusted his palms against his thighs and smiled.

Then someone called out, “Lights out,” and someone else answered, “Praise God.” Willy crawled into his bunk as the room filled with night.

All the times Willy had waited in all the different towns, he rarely knew what day it was, and never what time it was. It didn’t matter. But this wait was different. Waiting for school to start, he knew exactly what day it was and what time it was. This time, the wait might be worth it. He smiled into his pillow remembering his library card tucked safely into the cigar box. The distant train whistle clung to the night breeze. Light snores wiggled through the darkness.