Читать книгу Eco Living Japan - Deanna MacDonald - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHE SUSTAINABLE JAPANESE HOUSE:

PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE

Deanna MacDonald

“I do not know the meaning of ‘Green Architect.’ I have no interest in ‘Green,’ ‘Eco,’ and ‘Environmentally Friendly.’ I just hate wasting things.”

Shigeru Ban, 2014 Pritzker Prize laureate

Today, everything from coffee to skyscrapers comes with claims of sustainability, often complete with a ‘green’ label. The line between marketing strategy and truly sustainable design has diluted the concept of green building to the point where architects like Shigeru Ban, known for context-sensitive humanitarian design, distance themselves from labels seen as meaningless.

Sustainability starts not with a marketing department but in the first stages of design and follows through resourcing and production into use and eventual reuse. This should be Architecture 101 worldwide. Yet, truly sustainable architectural design is rare. This makes the projects in this book all the more remarkable. These houses embody Japan’s recent move towards (or perhaps back to) a sustainable living environment, albeit with cutting-edge technology. These are designs that work in harmony with their environment and the people who use them.

Shigeru Ban’s words echo the concept of mottainai, a Japanese term expressing regret for wasting an object or resource. Loosely translated as ‘waste not, want not’, it is at the heart of traditional Japanese building. Traditional Japanese architecture, based on the 100 percent recyclable building materials of wood, paper and tatami, has always prized and worked in response to nature. This tradition was subsumed in Japan’s modern evolution into one of the densest urban centers in the world. It never wholly disappeared.

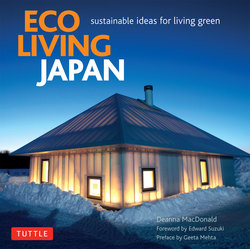

This book is about one of the most fundamental choices about how we live—our homes. Much of the world is now concerned with issues of sustainability, the environment and climate change. We all want to live in comfort and beauty. But is it possible to create a house that has beauty, functionality and sustainability? Can it be made affordable? This book offers an introduction to the unique ways Japanese design is responding to these concerns.

Pitched thatch roofs of traditional minka farmhouses.

The interaction of landscape and building in traditional Japanese architecture.

The Past

The elements of the Japanese house can be traced back to the aristocratic Shinden-style residences of the Heian era (794–1192), which were wooden post-and-lintel structures set on pillars, topped with pitched roofs and surrounded by gardens. The concept of the house evolved around the thirteenth century with the arrival of Zen Buddhism with its ethos of ‘eliminating the inessential’. A building was not just protection from the elements but an expression of the human relation to nature, with materials as unadorned and ephemeral as the world around it. Beauty and simplicity were one.

While both Shinden architecture and Zen philosophy originate in China, together they evolved into a new, distinctly Japanese aesthetic that resonates through Japanese architectural history. From the Muromachi period (1336–1572), various types of houses developed. There was the sturdy rural farmhouse, or minka, and the urban merchant house, or machiya. Aristocratic and samurai homes were built in the formal shion style, an evolution of the earlier Shinden style. As the tea ceremony grew in popularity, the ideal of the humble teahouse strongly influenced house design. The more relaxed Sukiya style, epitomized by the early Edo-era (1615–1868) Katsura Imperial Villa in Kyoto (see pages 136–7), found beauty in imperfection and ephemerality. The beauty of wabi sabi, once translated by Frank Lloyd Wright as “rusticity and simplicity that borders on loneliness”, was considered the height of sophistication. Sukiya interiors favored the unpredictability of asymmetrical modular layouts and varied materials and textures but linked all into a cohesive whole with strong lines and a muted color palette. And in all, attention to detail and craftsmanship were paramount.

These traditional Japanese houses were built from the inside out with the exterior reflecting the inner workings of the modular plan. As the European house gained a strong attachment to order and ornament, Japanese houses developed as simple flexible spaces with multiple uses and a ‘lightness’ that reflected the realities of living in an area of frequent earthquakes and Buddhist teachings of the transience of all things.

This functional approach resonated with early twentieth-century Modernists such as German architect Bruno Taut, who on visiting the seventeenth-century Katsura Imperial Villa in 1933 declared, “Japanese architecture has always been modern.” For Taut, trained in the Bauhaus with its mantras of ‘form follows function’ and ‘less is more’, Japanese architecture was a revelation: “The form and shape are not so important; the relationship with the environment is a more singular factor.”

This structural modularity came to be based on the size of an average tatami mat (generally 90 x 180 cm, though there are local variations), considered the correct size for one person to sleep on. The size of a traditional room is measured by its number of tatami, for example, a six-mat room. Today, the floor area of modern houses is measured in tsubo, roughly the equivalent of two tatami mats. It was about the same time that Leonardo da Vinci was developing his system of human body-based proportion that the tatami mat and, by extension, the human body, became the standard for proportion and scale in the Japanese house.

This human spatial scale is part of Japanese architecture’s close relation to the landscape and nature. Often the best part of a property was reserved for gardens and the house built on the remainder. The house design offered a flexibility of space and function that allowed for a fluid relation to nature. Inside, fusuma (solid sliding doors) and shoji (translucent sliding doors) create layers of spaces that could be opened and closed at will. In fine weather, entire walls could be pushed aside, opening the house to the garden. Twentieth-century architect Antonin Raymond, who spent most of his career in Japan, wrote: “The Japanese house is surprisingly free … one opens up all the storm doors, the sliding screens and sliding doors and the house becomes as free as a tent through which air gently passes.”

The garden became part of the experience of the house, the very basis of the concept of shakkei, or ‘borrowed landscape’. An engawa corridor created an intermediary space between inside and out. On summer days, it is part of the exterior experience but in winter and at night, with doors closed, it becomes part of the interior.

Wood is the traditional building material and generations of craftsmen learned to draw out the intrinsic beauty of the material. Art historian Yukio Lippit suggests that Japan’s architectural history is closely related to its ecological history. Builders knew their forests intimately and what wood was appropriate for each task, be it structural support in a large temple or expressing the ideals of wabi sabi in the materiality of a teahouse. It is worth noting that the high point of Japanese sculpture is considered to be the medieval wooden sculpture of the Kei School, many of whose members were also builders.

And importantly, the traditional house, made of natural materials such as wood, mud, straw and paper, was 100 percent biodegradable and recyclable. Most items were reused and reshaped over time and everything, from the structural materials to tatami mats and shoji screens, would eventually become compost or fuel.

Architectural historian Azby Brown has studied the development in pre-industrial Edo Japan of multifaceted sustainable systems in everything from agriculture to house building. After a period of deforestation led to building timber shortages and erosion from clear-cutting in the early 1600s, deforestation was halted, agricultural practices were improved and conservationist policies implemented at all levels of society. Daily life was premised on a concept of ‘just enough’; nothing was wasted. Brown notes that Edo Japan’s practices presage most of the basic tenets of modern sustainable design principles: connecting design and the environment, considering the social and spiritual aspects of design, taking responsibility for the design effects throughout the entire life cycle, ensuring long-term value, eliminating waste, using natural/passive energy flows and using nature as a model for design.

This all began to change with the advent of industrialization in the Meiji era (1868–1914), which also marked the introduction of Western architecture in Japan. Government and public buildings began to be built in Western styles, though the home remained fairly traditional until 1945. Some early twentieth-century experimentation by architects such as Sutemi Horiguchi and Antonin Raymond created a few exceptional homes mingling traditional architecture with early Modernism, but at the end of the war few were interested in the forms of the past.

Cities were rebuilt quickly and apartment blocks rose. The goal was rapid, modern redevelopment. Even the traditional houses of historic Kyoto, spared from the bombs of the war, were mostly destroyed by shortsighted redevelopment that began with Kyoto Tower, part of controversial modernization leading up to the 1964 Olympics. Today, it remains a jarring site on the city skyline though it has been overtaken by ever-rising nondescript towers and the mammoth, controversial Kyoto Station, arguably the most unnecessary building in Japan, emblematic of the loss of the traditional built environment in the later twentieth century. That Japan, so famed for its architecture in tune with nature and beauty, should have completely turned away from its building traditions for cities of concrete and steel still surprises first-time visitors.

The play of light and shadow in Yasushi Horibie’s House in Tateshina (page 64).

The play of texture and surfaces in the House in Nara by Uemachi Laboratory (page 42).

The Present

A common adage is that Japan is a country of contradictions. Contemporary Japanese cities are a tangle of skyscrapers, characterless mid-rises, wires and raised highways, and yet they still manage to charm. There is enormous waste but intense recycling. There is a great love of nature but an even greater desire to control it. Tradition is celebrated but newness is highly prized.

House building in Japan today is also full of contradictions. Japan has more architects per capita than any other country, about 3.8 times the number of architects than the USA. There is also a huge demand for new homes in Japan. This is surprising when one considers that the population is shrinking and expected to decrease by 30 percent by 2060, and that today about 17 percent of Japanese homes are left vacant; 2015 estimates suggest there are at least 8 million akiya (empty houses) in Japan. Half of all houses are demolished before 38 years (compared to 100 years in the USA). This is closely linked to the fact that houses lose 100 percent of their value after about 30 years, condos after 40 years, because insurance companies will not insure older homes. Some studies put the full loss of value as low as 15 years. It is thus not surprising that contemporary Japanese homes have been called ‘disposable’.

Land costs play a large factor. Cass Gilbert, architect of the 1913 Woolsworth building in New York, called the skyscraper “a machine for making the land pay”. This is a lesson Japan has learned well. When a home is sold, it is really the land that purchasers are buying. Usually the house is demolished, even if renovations cost less than a new home. And often more profitable multistoried apartment blocks rise in place of the destroyed single-family home, assuming the plot is large enough.

As land prices are exorbitant, most landowners have small, irregular plots. Constantly divided and subdivided as it is sold or divided among each generation, every centimeter of land is valuable, and it is not uncommon to have plots only a few meters wide or in polygonal shapes. Local building regulations are often fairly permissive. Each individual plot is considered as an entity, not as a part of a neighborhood. So clients, knowing the house will not hold long-term value or pass to the next generation, build to their tastes. In these distinct circumstances, architects are often encouraged to create something unique. Houses can take on fantastic forms and whether practical, livable, sustainable or not, often feature in the pages of design and architecture publications worldwide. They can be beautiful, whimsical or daring, yet despite the effort and costs involved, even high-end design houses are rarely built to last. Most owners put in little to no maintenance once their house is built. Why invest in a structure that can only lose value? Thus, even in sought-after neighborhoods, houses are frequently left to rot.

How did this tatekae (scrap-and-build) culture come about? On the philosophical side, scholars will point to a love of the new as embodied in Japan’s principal Shinto shrine, the Ise Jingu, which has been rebuilt every 20 years since the seventh century. Its architectural renewal remains a potent symbol of spiritual purity. The Buddhist belief of the transience of all things is also cited as a rationale.

Wabi sabi aesthetics meet Bohemian design in A1 Architects’ A1 House in Prague (page 222).

More concretely, historians point to the aftermath of the Second World War. One million people were homeless and structures were quickly and shoddily rebuilt. By the 1960s, as Japan began to recover economically, these structures were torn down and replaced, in a cycle some say continues today.

Geography also plays a part. Japan’s frequent earthquakes contribute to the sense of impermanence related to housing as traditional wooden buildings were often destroyed by a quake or in post-quake fires. The steady advance of seismic technology has led to shifting building codes. Since the Great Kanto Quake in 1923, building codes have been revamped after every major earthquake: in 1950, 1971, 1981, 1987 and, most recently, 2011.

However, most homes demolished today do meet the latest standards. Nevertheless, building companies, particularly since 2011, advertise their high seismic standards and encourage the demolition of older ‘dangerous’ houses in favor of new ‘safe’ ones. Some call this ‘fear selling’, and not necessarily based on structural safety. The highly profitable construction industry in Japan has evolved on the basis of this scrap-and-build system. Just how, and if, this system can be changed remains to be seen.

And, of course, construction comes at an environmental cost. Building in the developed world produces over 40 percent of carbon emissions worldwide and 40 percent of energy consumption. About 50 percent of raw material goes into building, and waste from the construction industry is adding to an already overburdened disposable and recycling systems.

The economist Richard Coup has called Japan’s scrap-and-build housing industry an “obstacle to affluence”. The cycle means that buying a house is not an investment as it is in most developed countries. This economic factor also makes it even more difficult to convince builders to invest in more sustainable homes. Yet, there are those who are willing to try. Every project in this book is exceptional and represents the growing number of forward-thinking homeowners, designers and craftspeople who are placing their architectural bets on a more sustainable future. The projects explore innovative and beautiful houses in Japan and abroad that push design and technology in new and old ecological directions.

Chapter 1 considers how bringing nature into the home can make it a healthier, happier and more sustainable living environment. From Yasushi Horibe’s framing of nature in the House in Tateshina to the link between house and landscape in Uemachi Laboratory’s House in Nara, all projects suggest that nature offers answers to green building issues.

Chapter 2 considers how traditional Japanese architecture is helping reinvent the houses of the twenty-first century. Lessons on how to live more sustainably are taken from a myriad of sources, from the architecture of the Ainu people (Kengo Kuma’s Même Meadows) and an Edo-era aristocratic villa (Edward Suzuki’s House of Maples in Karuizawa) to a rural farmhouse (Lambiasi + Hayashi’s Mini Step House).

Chapter 3 looks at ‘smart’ houses that aim to make the home as resource-efficient as possible through innovative high- and low-tech design, from Atelier Tekuto’s experiments with modern materials to create energy efficiency in the A-Ring House to the passive energy principles of Key Architects’ House in Karuizawa.

Chapter 4 looks at repurposed buildings and renovation projects that demonstrate how old buildings anywhere can be recreated as contemporary, stylish and sustainable, from a dilapidated merchant townhouse in Kyoto turned luxury residence to an old rural farm house given a new life for a young family.

Chapter 5 looks outside Japan for buildings inspired by Japan’s eco traditions, from a townhouse in urban Toronto to a forest retreat in Norway and a wabi sabi house in Prague.

The Future

Today, particularly since the disasters of March 2011, an ever-growing interest in sustainable living has made environmental design one of the most discussed topics in Japan. Designers, architects and homeowners are reappraising the naturally ‘green’ qualities of historic Japanese architecture and exploring how it can work with emerging sustainable technology. With this unique mix of past and present, tradition and technology and love of fine craftsmanship and innovation, Japan is in many ways a natural leader in eco architecture. The houses and ideas presented in this book suggest just how Japan could become an international model of sustainability.

Yet, to expand these ideas from individual projects to society at large, political will, far-sighted legislation, corporate compliance and economic investment are needed. Voluntary standards and certification schemes to measure sustainability in the built environment, such as LEED (Leadership in Engineering and Environmental Design) in the USA, BREEAM (Building Research Establishment’s Environmental Assessment Method) in the UK and CASBEE (Comprehensive Assessment System for Built Environment Efficiency) in Japan, all attempt to guide builders into good practices. None are mandatory but grow in influence.

The upcoming 2020 Olympics in Tokyo are expected to bring environmental issues forward. The 1964 Olympics in Tokyo were considered a watershed, transforming post-war Tokyo into a model of modern urbanism, albeit a 1964 model. Many hope 2020 will be just as transforming, readdressing Tokyo’s unsustainable development of the past decades. There are proposed plans to reduce car traffic by completing ring roads, to improve the visual landscape by burying the tangle of wires that hover over almost every street and even to remove the elevated highways from above Nihonbashi, the center of historic Tokyo, that were built in the rush to prepare for the 1964 Games, and to increase the use of renewable energy in Tokyo from 6 to 20 percent by 2020.

Many of the houses in this book are built with modern materials and techniques, yet all express some aspect of the traditional dynamics of Japanese architectural space and sensibilities. This desire to connect to a more sustainable past to build a more sustainable future is growing, particularly among younger generations who have grown up in dense urbanism and for whom old ways are intriguingly new. But as society turns green, will the wider construction industry follow? Japan builds some of the most advanced, seismically sound buildings in the world. Can it start to build some of the most sustainable? With a built heritage that is a model of sustainability, a recent history that is not and a new generation concerned for the future, Japan has choices to make. As shown by the projects, houses and homeowners in this book, Japan has the tools needed to lead the way internationally to a more sustainable built environment. The question remains, will it?

Traditional Ainu architecture meets high-tech construction in Kengo Kuma’s Même Meadows (page 116).