Читать книгу My Body, The Buddhist - Deborah Hay - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеforeword Susan Leigh Foster

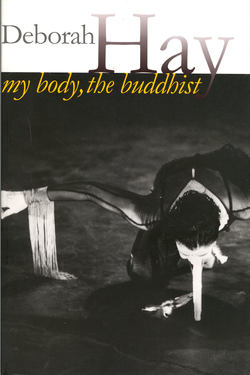

Introducing Deborah Hay’s body-as-Buddhist. Such an agile body, capable of lightning-quick transformations—floppy then precise, always deft, full of buffoonery and deadly serious in its commitment to each gesture. It gallops, swaggers, tip-toes, and falls gently backward into the embrace of space. Scrambling or gliding to standing, it grimaces. The softest leaps, the most preposterous gestures, it happily cavorts before slowing to stillness, a dynamic tranquillity. The flexibility, the unpredictability of its attitudes draw us toward it. It gazes back at those who view it with a generous invitation to be looked at.

This body, it is proposed, practices a religion renowned for its skeptical stance toward religion. It performs as teacher, oracle, and companion in the investigation, not of spirituality, but of consciousness itself. Alternately a corporeal provocateur that poses the question of consciousness and the medium through which the investigation of consciousness takes shape, the Buddhist body moves matter-of-factly through its day.

Hay has cultivated this body, discovered and rediscovered it over many years of dancing. In training to make and perform dances, she attends to the body’s changeability. She explores the ramifications of multiple, distinctive metaphorical framings of physicality. Body, in turn, has offered a kind of dialogue—probing, assessing, reacting, and instigating—in response to Hay’s various queries. Close and consistent attentiveness to this dialogue forms the basis of Hay’s regimen for learning to dance and also generates the motional matter from which her dances are made. For Hay, choreography emerges from her ongoing reflections about bodiliness.

My Body, The Buddhist documents this generative play between corporeality and consciousness and between the dance of everyday life and dance as a theatrical practice. The text’s non-narrative account of a choreographer’s daily work mingles descriptions of living, training, creating, and performing so as to illuminate the integral relation between artistic vision and the daily pursuit of that vision. Fleshing out the body’s “daringly ordinary perspicacity,” she sustains the quizzical, illusive maverickness of body even as she illumines corporeal existence through her descriptions of it.

ALTERNATIVE ARTISTRY

As a dancer with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, a participant in the Judson Dance Theater performances, an independent choreographer located in Austin, Texas, and as world-touring performer and teacher, Hay has elaborated a powerful alternative dancing practice. She is continuously upheaving our assumptions about dance and the body. She shows us how interesting stillness is, and how quickly physical commitment can change from one action, persona, or image to another. Her dances elaborate a theatricality that appears pedestrian, intimate, and casual one minute while filled with wonderment, alterity, and sumptuousness the next. Above all, her work invites us to laugh at our own seriousness and take in the dancing seriously, both at the same time. Hay’s sustained dedication to alternative choreographic values such as these is an extraordinary achievement, especially during this era of lack of support, monetary and otherwise, for the arts.

During the 1960s, when Hay came of age as an artist, art-making was one of several alternative cultural practices through which mainstream values were critically interrogated. Works by Cunningham, Paul Taylor, Eleo Pomare, and the Judson choreographers all pushed at the boundaries of acceptable dance movement and introduced alternative vocabularies and stagings for danced performance. One of the results of their efforts has been to make evident the specificity of the relationship between technical competence and choreographic vision. Unlike ballet, where standard criteria of evaluation and a universalist ideal of expertise are developed, Hay and others of her generation have proposed projects that require radically alternative sets of physical skills. Unlike modern dance pioneers such as Martha Graham and Doris Humphrey, whose vocabularies seemed to issue from pan-human psychic dynamics, choreographers from the 1960s shifted the focus away from psychological origins and toward the physical matter of dance-making. Their work demonstrates how each new choreographic project requires special skills and hence special training in order for the dancer to acquire those skills.

Hay’s work exemplifies a radical and fully realized vision of this kind of alternative training program and choreography. Many contemporary choreographers blur or obscure the ways that training inculcates aesthetic values by working with pick-up companies whose dancers acquire an amalgamation of dance styles, such as release work, contact improvisation, and ballet. Hay, instead, nurtures the relationship between her approach to dance training and performance, and she stands by its integrity. As a result, her dances look entirely unique and so do the dancers who perform them.

Hay has pursued her alternative artistic practice as both choreographer and teacher. From 1980 to 1995 Hay conducted a series of large group workshops in Austin, Texas, each meeting daily for a period of three to four months and culminating in performances of an evening-length work developed over the course of the workshop. Here again, Hay’s commitment to the intrinsic connection between learning dancing and making dances is evident. Hay organized each workshop around the exploration of a specific theme, and then allowed the dance to develop from the daily practice of this theme. Rather than instruct students in a standard repertoire of technical skills and then proceed to fashion a dance, Hay organizes both the acquisition of technique and the choreography around a focused inquiry into bodiliness.

Hay’s workshops have made the most brilliant dancers better dancers, but they have had equal relevance for people in other professions. Architects, therapists, writers, and construction workers have all participated in these annual gatherings. Here a heterogeneous alternative group of individuals gains bodily eloquence, perceptual acuity, and collective sensibilities that enrich the Austin community and the international dance world. The workshops carry forward the 1960s impulse to include all bodies in dancing, to claim that all bodies can dance, yet they deepen that impulse by requiring such a powerful commitment to the process of physical inquiry.

Hay’s alternative artistry has challenged general assumptions about what dance is, and she has also turned its critical reflexivity toward her own artistic practice. My Body, The Buddhist witnesses Hay’s willingness to examine the limits of her own artistic practice. In one instance, she recounts her abhorrence at the thought of making a dance to a specific piece of music, her sudden awareness of the strict limits this has placed on her own choreography, and her reluctant resolve to embark on the project. Rarely do we glimpse the role of this kind of instrospective reflection in the process of art-making. Hay’s staging of the dialogue between body and consciousness generously allows us to view it from many perspectives.

My Body, The Buddhist describes the development of several recent works, focusing especially on how the dances issue from Hay’s daily dialogue with body. Hay’s previous book, Lamb at the Altar: The Story of a Dance, documents the process of creating and producing a single evening-length work developed during one of her large group workshops. In it Hay recounts her responses to the distinctive physicalities of individual participants and the staging of those bodies as characters and actions. Alongside this discussion of bodies and movement, she reports the negotiations concerning a performance space, costuming, scenery, and lighting that are entailed in the mounting of any production. The juxtaposition of these different aspects of dance-making provides an invaluable perspective on how an artist lives and works in these times. My Body, The Buddhist continues this chronicle of an artist’s work, yet it looks more introspectively at the relationship between a choreographer’s daily movement practice and choreographed performance, and it illuminates the dancer’s constant and daily attentiveness to body’s articulateness.

“WHERE I AM IS WHAT I NEED, CELLULARLY”

One of the dominant and sustaining metaphors in Hay’s cultivation of physicality is her postulation of body as the ever-changing cumulative performance of seventy-five trillion semi-independent cells.* In her daily training, Hay practices sensitizing herself to the mobility and responsiveness of body as so constituted. For example, she may use as focus for herself and her students such statements as “Where I am is what I need, cellularly,” or “Alignment is everywhere,” or “What if Now is Here is Harmony.” Such instructions cultivate the differentiatedness of body—the many distinctive possibilities for physical articulation—and the attentiveness required to track and take note of the body’s inclinations. They also challenge the dancer to open up to an immense range of neuromuscular possibilities and to validate each of these new impulses. Any and all cellular initiatives are worthy of attention. They are all what the dancer “needs.”

In her daily practice of dancing and in the classes she teaches, Hay’s use of these directives summons the dancer into the creative and also critical process of moving in a new way. Hay spends much of her practice time exploring their implications and refining them for use in teaching. Each of her large group workshops has revolved around one of these directives, using it to provide the focus for daily movement investigations and for the final performance. For example:

1987: I invite being seen drawing wisdom from everything while remaining positionless about what wisdom is or looks like.

1988: I imagine every cell in my body has the potential to perceive action, resourcefulness, and cultivation at once.

1989: I invite being seen not being fixed in my fabulously unique three-dimensional body.

(For comprehensive documentation of the workshops, see the list of performance practices included in this volume.)

Koan-like in their spare summoning of full attentiveness, these statements acknowledge the constant changing of body in consciousness.

Students in Hay’s classes spend anywhere from forty minutes to three hours experimenting individually and collectively with one such directive as the generative principle and conscious focus for dancing. Throughout their exploration, Hay speaks very little. Rather than stipulate or enforce a specific way of doing things, Hay encourages students to investigate on their own, and interactively with others, the myriad movements the directive inspires. As the convener of this group exploration, Hay offers occasional new perspectives from which to continue exploration. If, for example, they are investigating “Alignment is everywhere,” Hay might suggest the following ways of “playing” such a postulation:

There is no one way alignment is everywhere looks or feels.

The whole body at once is the teacher.

Thank heaventz for the choice to play what if alignment is everywhere.

Your teacher inspires mine.

It doesn’t matter if it is true or not. Just notice the feedback when you play it.

Your practice informs my practice.*

Hay reminds students that they are teaching themselves by attending rigorously to the body’s impulses. No body’s responses will look the same. Each body can inspire others. All bodies can and should delight in the marvelousness of practicing dancing.

Compare this approach to dance training with a generic college-level dance class in either ballet or modern dance. Such a class stresses the body’s ability (and inability) to conform to specified shapes at a given time. The technically proficient body is one that accurately and efficiently responds to the specifications. Embedded in each shape and limited to each temporal phrasing is a hierarchization of body parts, a valuing of parts in relation to a whole, through which the aesthetic ideal is conveyed. The dancer works to master these shapings and timings and, through the process, learns what the body can and cannot do. The body succeeds or fails, becomes recalcitrant or insufficient. It functions in reactive response to the will being exerted over it.

Hay’s approach, in contrast, constructs body as a site of exploration to which the dancer must remain vigilantly attentive. Body does not succumb to the dancer’s agency—striving, failing, mustering its resources to try again. Instead it playfully engages, willing to undertake new projects and reveal new configurations of itself with unlimited resourcefulness. Students receive no approval or criticism for engaging in these explorations, nor do they learn to hate the body for its inadequacies. Rather, they orient toward body as a generative source of ideas. Their reward comes less from mastering specific skills and more from the sense of the body unfolding as a site of infinite possibilities.

The choreographic form of Hay’s dances coalesces out of the exploration of these same directives. (Her renowned trilogy The Man Who Grew Common in Wisdom developed from the three images for 1987, 1988, and 1989 cited above.) Increasingly attentive to what the directive suggests, Hay and her students refine movement into similar shapes, repeatable actions, and identifiable phrases. For her large group dances, Hay coordinates the individual contributions of all participants, tuning them to the emerging score for the evening-length piece. For her solo pieces, Hay often extracts impulses from these variegated responses, sequencing them to suit a single body’s ability to elucidate the directive’s shaping of physicality. While developing one of her dances, Hay may enact distinct images that specify a shaping or quality of motion. But in taking on a shape or phrase, she is not evaluating body’s conformance to an ideal aesthetic. Rather, she works to open all parts of the body—all seventy-five trillion cells to the image, and at the same time she tunes to the dialogue between body and image, listening for what each might say to the other.

Hay distinguishes between the practice of exploring the directives and choreography in this way:

They are two different animals. The practice is like the conscious heartbeat of the dance. The choreography is simultaneously the conscious choices I am making within the form.*

While practicing the directive, Hay makes certain choices and decisions, some of which she retains in subsequent practices so as to build an established sequence. She does not mold patterns of movement in order to express an image, but instead, selects from her dialogue between body and image impulses that most vividly reflect and amplify her experience of working with the image.

Once the movement material has been choreographed so that it congeals in a reliably repeatable sequence of actions, Hay re-infuses the performance of the choreography with focus on the directive. Using the choreographic form as a kind of stable reference, she reanimates each action with consciousness of the practice that produced it. Earlier in her career, Hay worked with several such images in the making and performing of each piece, moving from one to the next as the choreography progressed. Over a ten-year period of conducting large group workshops, she reduced and distilled her practice of images to a single meditation directive that now presides over and and focuses each evening-length work. Throughout the creative process of practicing, training, making, and performing dances, Hay continues to listen to the dialogue between body and idea. It is this cyclical listening process that My Body, The Buddhist documents so effectively.

Over the years, Hay’s investigation of bodiliness has resulted in remarkably distinctive dances. In Voilà (1995), for example, the dancer performs a twenty-five minute solo full of startling non sequiturs that nonetheless cohere around a dream she recounts several times during the dance. She then reiterates fragments from the dance as accompaniment to her recitation of a description of each movement’s intended meaning. In this diagnosis of the dance as part of the dance, movement’s meaning explodes into a marvelous profusion of semiotic possibilities. Hay’s analysis of each move shows it to signify both more and less than its conventional usage. Exit (1995), in contrast, elaborates on the dancer’s focus, on the ability of body and face to project a sense of moving into past or future over a seven-minute cross from one side of the stage to the other. The stunningly simple structure generates multiple resonances around the word exit.

Hay’s script of Voilà, included in this volume, provides a wonderful documentation of the diverse images contained within the choreography, and the changes to their meanings that result from sequence and context. It also challenges as it expands our notions of how to notate dance by calling attention to many of the ways that movement can be described and characterized. Having witnessed the dance first in silence, viewers then re-view the dance accompanied by verbal description, all phrased in the past tense, even though the speaking dancer performs them at the same moment she describes them. Viewers see movements from the dance isolated and explained, as if the spoken text revealed what the choreographer was “really” thinking. Yet the descriptions emphasize very different aspects of the movement, and their sequence is preposterously nonlogical. Hay refers to some of her actions in terms of their kinesiological components: “An arm poised el-shaped in front of her face. The wrist hung loosely.” Other times, she emphasizes the metaphors movement can evoke: “She was a cartoon, playing horse and rider, but serious about the rules.” A glass of water she is drinking turns suddenly into a microphone and then into a horse’s tail. The varieties of description, the non sequiturs, and the use of past tense all unsettle the relationship between speech and action, underscoring the absurdity of the attempt to label movements, and ironizing the role of the choreographer as originator of movement’s meaning.

At the same time, the talking creates a space full of conjectures and conjurings. It supports the dancer’s restless exploration, the trying out and on of images. Both the dancer and the description mean differently at different moments. The viewer soon realizes that there is no real or deepest interpretation of the action, no message to be consumed. Calling attention to the relationship between location of iteration, whether spoken or danced, and its meaning, Hay’s full-blooded irony plunges viewers into the experiencing and enacting of events while retaining a reflexive distance from them. Voilà stages a series of “what ifs” that encourages viewers to savor the process of meaning-making. In so doing, they may just learn that where they are is what they need.

SACRED DANCING

With respect to her own performances and also to dancing in general, Hay comments that the label “sacred dancing” is redundant. Dancing is always and already sacred in the way that it conjoins body and consciousness. Issues concerning religion and spirituality have permeated Hay’s work for many years. In her writing she makes references to an eclectic group of religions including Christian, Buddhist, Hindu, and Jewish traditions. In her dancing she elaborates strong connections to the spiritual practices of yoga and the martial arts. Yet Hay’s gestures toward religious experience have little to do with institutionalized worship or with New Age spiritual quests. Instead, she finds the sacred in looking at the daily through the lens of a cultivated physicality that is not being used in the service of anything else.

How does she look at the daily? and how does she maintain focus on physicality? As part of her training, Hay projects the existence of an observer who is watching her exploration of bodily cellular consciousness. Hay further projects a second observer who watches the first. Hay’s moving body is thus watching itself moving and watching itself watching itself. Many theories of consciousness do not permit body to be consciously aware of its own activities while in motion. Many forms of prayer and meditation, even Buddhist meditation, encourage practitioners to sit and be still. In defiance of this opposition between action and reflection, Hay asserts the possibility of a consciously aware and critically reflective corporeality.

The best way to understand Hay’s “sacred” dancing is to watch her dance or to participate in one of her courses. For those who want to imagine or remember her performance, My Body, The Buddhist offers a reading of body equivalent to her dances. That is to say, Hay’s writing, never sentimental or nostalgic for a body that words only diminish, compartmentalize, or capture, crafts words with the same playful investigativeness that she implements in her choreographic process. This staging of a meditation on bodiliness, in all its devotion and doubt, deepens our understanding of dance and dance-making. Like her workshops, however, My Body, The Buddhist also makes the experience of physicality available to readers from many different walks of life, inviting them to share the dance.

_____________

*Hay recently revised the figure up from fifty-three trillion cells, in keeping with the latest scientific tallies on the body’s cell count. She reminisces: “When I began this practice in 1970 I was using the image of 5 million cells. That is how time has changed the body!!” Personal communication.

*Hay explains that “These coaching directives formed during my experiences dancing with large groups of untrained dancers dancing.” Personal communication.

*Personal communication.