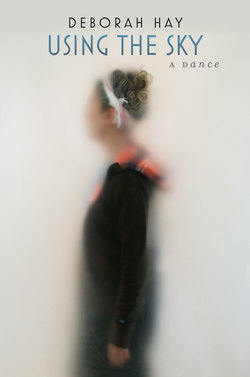

Читать книгу Using the Sky - Deborah Hay - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеforeword

The words and ideas contained in this remarkable book by Deborah Hay mark a particular period in her creative practice, from 2000 through 2015. With ample wit and wisdom, her nuanced observations illuminate her substantial contribution to dance. Autobiographical in style, Using the Sky strikes me as Deborah Hay’s most recent self-portrait. It is like the portraiture long used by visual artists as a self-referential record of their practice, in which the evolving technique, choice of palette, scale, and materials contain volumes of information for the viewer. The words of Deborah’s “self-portrait” move continuously, and her brushstrokes are as intricate as they are wildly generous.

Those fifteen years bracket a prolific body of choreographic creation, wherein heightened opportunity broadened the points of access to her work worldwide. The support and involvement of many artists played defining roles in propelling this trajectory, and it was a fertile period indeed. Yet as she describes it, this chapter of her work almost didn’t arrive.

My own curatorial perspective on Deborah Hay’s work comes out of an artist-centered background. I have learned that her singular impact is far-reaching, her use of language one of her uniquely vital tools. The title of this book, Using the Sky, I interpret as an invitation.

WHIDBEY ISLAND (SUMMER SKY)

My first encounter with Deborah Hay was in August 1999, when I found myself in an unlikely location to meet one of the originators of Judson Church and the postmodern dance movement that was spawned throughout the downtown dance scene of New York during the 1960s and 1970s. We met on Whidbey Island, in the San Juan Island chain off the coast of Washington State. Deborah was there to run her intensive Solo Performance Commissioning Project for a predetermined number of people who had signed on as participants.

I knew one of the participants—the Australian-based dancer and choreographer Ros Warby, whom I had worked with as an artistic director at the Portland Institute for Contemporary Art—and it was through her encouragement that I began to learn about the singular Deborah Hay. Ros had invited me to see the “showing” that would happen on the final day of the project.

Ros had made the trip from Australia in order to take part. There were many other dancers/movers/performers who similarly came from far off, like Deborah herself. I pulled into the gravel parking area of the Whidbey Island Center for the Arts, thinking: “Of all the places to hold a dance intensive, how on earth did she pick this one?” This is a place in the Pacific Northwest known mainly for its military base, crab fishing, timber, and rain.

Sitting inconspicuously on the floor, I was among a group of twenty-plus people in their comfortable layers and bare feet, one of the only people watching. The full majority were involved in doing. Deborah was readying them in a warm-up while offering what seemed to me unusual and random instructions. Not being familiar with her working process, I could not make sense of the words that the performers embraced with head nods and full absorption. Hay walked over to welcome me and handed me a short printed program. They would all be performing their solo adaptation of a work entitled Fire.

Not only had the performers traveled some distance to arrive at this moment, they came from vastly different performance backgrounds as well. Watching them all perform their solo adaptations simultaneously was akin to hearing numerous languages being spoken at once. I knew they were “speaking” from the same text, although the movement itself spun off into radically different results. I could not decipher what was being “said” or where to direct my attention. The experience of the work was as odd as it was captivating.

Driving Ros Warby to the ferry terminal afterward, I asked her questions about the process I had witnessed. While there had been pattern, shape, and a rich dimensionality, I could not recognize the choreographic system underpinning Fire.

NEW YORK (WINTER SKY)

I saw Fire again much later at Danspace Project in New York as part of an evening entitled Boom, Boom, Boom. This time Warby and Hay each performed her own adaptation of the material before an audience of dance practitioners and others active in the downtown art scene, where exposure to experimental work is a part of one’s daily diet. This Fire was a performance in which the diligent practice of Hay and the articulation of Warby bolted forward into a lasting and potent recognition of Deborah’s work for everyone there. I saw once more the piece that I had experienced on Whidbey Island, but with heightened resonance. This Fire remained perfectly absurd, but left a glorious charge in the air.

In my subsequent discussions with curatorial colleagues, they expressed frustration about the limited access to Deborah’s work outside of Danspace and Movement Research in New York. Deborah was highly esteemed in postmodern dance and by practitioners of improvisation, but those running dance-presenting organizations nationally had their focus elsewhere.

Deborah was part of Past/Forward, a brilliant survey of the choreographers and artists from Judson Church that Mikhail Baryshnikov had commissioned for the White Oak Dance Company. There was much anticipation at the outset; a healthy touring life and critical acclaim followed. Past/Forward amplified the legacy of the creative research and work of the Judson Church dance scene, and by design, it also brought greater awareness of the artists who had continued to create work these many decades later. As Past/Forward continued to tour the world, Deborah returned to the studio.

I began to realize how Deborah’s precisely crafted instructional phrases are woven into a “score.” Her scores are remarkable in their own right and truly “impossible” to execute if one were to assume there is a right or correct way of yielding a result. Her dances are meant to provoke what she calls a “dis-attachment” from learned techniques, in service to being in the very potential of the performance exactly while it is taking place. It likely goes without saying that this is of great value to performers themselves.

I didn’t quite know how to convert this kind of “process-based” information into a curatorial/presenting framework engaging the interests of audiences. How might I enlist audiences to support dance that is not like the dance they think they know, but possesses a new singularity and resonance?

In hindsight, I was beginning to ask audiences to do what Deborah Hay was asking performers to do: explore the possible discovery of something exceptional by dis-attaching from what had already been learned through previous experience.

In 2003 Deborah contacted me to revisit an earlier invitation. She was interested in translating her choreographic practice onto “professional dancers,” some of whom were also acknowledged choreographers. Her choice to select and invite highly accomplished artists for the work was a marked departure. Rather than perform the piece herself, she would be applying her experimentation and ideas through their individual capacities and technique. Danspace had agreed to commission it, and I was more than happy to commit my organization’s support early on. The project was called The Match.

The dancers whom Deborah had initially envisioned formed the quartet of The Match: Ros Warby, Wally Cardona, Chrysa Parkinson, and Mark Lorimer. In 2004 The Match premiered at Danspace, the organization that had long served as Deborah’s artistic home in New York City. The Match illuminated to beautiful effect her nonlinear provocations when placed in collision with the achieved techniques held to by each of the dancers. It was evident that their collective approach ensured that the process itself was as useful to their practice as it was to Deborah’s. Through destabilizing/unhinging the experiential structures that these exceptionally proficient bodies had powerfully in place, something sublime and Other emerged for all of them. The Match was profoundly expressive, a spectacular moment acknowledging the depth of Hay’s practice. After the premiere there was resounding agreement that this was a major work of art. Later that year Deborah Hay received the 2004 Bessie Award.

PORTLAND, OREGON (AUTUMN SKY 2004)

I presented the solo adaptations of The Match as part of the 2004 Time-Based Art Festival at the Portland Institute for Contemporary Art, and as at Deborah’s premiere in New York, the audiences were riveted. Fortuitously, I was hosting a group of artistic directors and dance curators from France during that year’s festival, and they were all immensely interested in Deborah Hay after they saw the performance. At lunch the next day they excitedly pressed me about where she came from and how it was possible that they didn’t know her work when they knew so much about so many other American choreographers. It occurred to me to compare Deborah Hay to the American painter Georgia O’Keeffe, who had also chosen to leave New York and its attendant ambitions, for the desert landscapes of the Southwest, in order to “be able to work.”

MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA (SPRING SKY 2008)

I invited Deborah’s piece If I Sing to You to the Melbourne International Arts Festival, where I was then serving as the artistic director. By then her work had widely penetrated into Europe, where important dance festivals and artistic directors (Montpellier in France and Dance Umbrella in the United Kingdom, for example) had invited The Match, and her mobility was increasing. Deborah was now receiving commissions and well-warranted acknowledgment. The circulation of her ideas had broadened, and her explorations with exceptional professional dancers had continued to deepen. The project had been commissioned by William Forsythe through his own dance company, another hugely respected artist propelling Deborah’s ideas to a larger audience, within a relationship that continues to this day.

If I Sing to You had no music (there would be some vocalizations generated by the dancers into individual, spontaneous songs). The lighting was diffused, without dramatic embellishment or color, and the scene design was the stage itself and a white floor surface. The running time was approximately one hour and twenty minutes, with no intermission. All of the cues were determined by the movement changes of the performers, which they would decide in situ. The dancers were all female, and they were responsible for selecting either a male or female costume for each performance. Deborah had one rule about costuming—both genders had to be represented onstage—and this varied with each performance.

As with Fire in New York (and with The Match everywhere it went), the audience at the opening night of If I Sing to You was palpably rapt. Its success was a result of the sheer honesty of Deborah’s practice remaining utterly on course.

LOS ANGELES (SPRING SKY 2015)

Deborah completed a residency in Los Angeles through the organization I now run, called Center for the Art of Performance at UCLA. Not surprisingly, her interest lay in exploring new language for describing dance itself. Her approach involved the invention of various word games and interactions with artists, dancers, and a more general audience. She was busy with new epiphanies, and her experimentation revealed many layers to be mined further. I can only anticipate that wherever her new revelations lead, her powers will be formidable in every direction toward which her practice bends.

I recently asked her about her keen interest in language, and she responded: “What my body can do is limited. This is not a bad thing because how I choreograph frees me from those limitations. Writing is then how I reframe and understand the body through my choreography.”

Being freed from limitations is what I have witnessed and experienced in Deborah’s entire body of work, which stands as a gift to those who are engaged in her orbit. Deborah is in complete possession of the skills and disposition to upend restraints. Most typically she has set her sights on those restraints from which artists in particular draw. But perhaps all of us more generally can examine the assets of what we have spent years perfecting, illustrating, and maintaining and consider them anew. Perhaps in doing so we can in some way be liberated from the limitations that our own maturing skills unconsciously present to us later on.

Using the Sky is indeed a generous invitation to draw from Deborah’s accumulated observations a departure point from what we already know, so that we can arrive in places we may otherwise never have imagined.

Kristy Edmunds