Читать книгу The Road Out - Deborah Hicks - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER TWO

Elizabeth Discovers Her Paperback

Even before our class began on a warm morning later that same week in June, our two floor fans were already working furiously. The sun’s rays had begun to warm my ground-floor classroom past the comfort level. From the second floor came wafts of something that smelled toxic. The floors upstairs were being stripped, and it was of no consequence that the odors might be disturbing, or even unhealthy, for the children and teachers working on the floor below. An incident that generated anger and mistrust throughout the neighborhood crept into my thoughts. In the 1980s, several children had had to be carried out of the school on stretchers because of toxic fumes from a nearby paint shop. I wondered for a moment if the fumes we had to live with on this summer morning were safe for the girls, and for me. But I didn’t have much time to linger on my latest source of anxiety. The girls would be coming in soon.

I pushed back my worries and looked around, admiring the handiwork of my teaching preparations. One thing I had quickly discovered was that compared to the increasingly regimented curriculum that teachers were compelled to offer during the year, summer school was like a tabula rasa. For four glorious hours each day, a resourceful teacher could offer the reading curriculum that she felt her students needed, not the prepackaged schemes marketed to desperate school districts as the latest fix for poorly performing students. All that spring and into the early weeks of summer, I had embarked on a hunt for the perfect summer reading for a class of girls, and not just any girls. Several of my students were still getting their feet on the ground as readers. Jessica and Alicia read haltingly, and either of them could give up easily if a book seemed too hard or too long. The landscape of the girls’ lives made things different, too. How many novels for young readers feature young heroines who are poor and white, and who face anything close to the obstacles faced by my students? Today as I looked again at the bookshelves, I was sure I had finally found the book that would pull my students into its beautifully written story about a girl’s life.

The novel was written by a woman with Appalachian roots and was set in West Virginia. Ellie Farley, the young heroine of Cynthia Rylant’s A Blue-Eyed Daisy, is a pretty girl with long fair hair, blue eyes, and rotting teeth. At home, there are her four older sisters, ensconced in their teenage worlds. There is her hard-drinking father, Okey, out of work after a mining accident, and her stressed-out mother, who has shut the door on her feelings of rage and disappointment. Okey sometimes loses it in a bout of drinking. At those times, Ellie hides and cringes, while her mother absorbs Okey’s verbal rantings and occasional punches. Most of the time, however, Ellie struggles for connection, even with her damaged father. The novel chronicles “some year,” as Ellie inches closer toward her twelfth birthday.1

I felt a sense of anticipation that any book-loving teacher would recognize. For months, I had worked day and night to plan for our special summer class. For over a year, we had met after school each week, building trust and the ability to listen to one another. Now the day was ours and—even with the drippy Ohio heat and the fumes coming from upstairs—I was ready.

I straightened an old family quilt I used that summer as a cozy cushion for our meeting circle. Sometimes we sat right on the carpeted floor because the girls were so small—and so was our group. I couldn’t get Jessica out of bed to come to my summer class every morning, so often we ended up with four students who had attended my Monday afterschool class that spring—Adriana, Alicia, Blair, and Shannon—and one who hadn’t, Elizabeth. This was Elizabeth’s first time in an intensive summer class devoted so strongly to reading and talking about literature, and she wasn’t at all sure how she felt about things.

Elizabeth was the kind of girl who harbored secret feelings of anger and longing. She was a passionate girl, always in search of something. Elizabeth tended to throw herself into things headfirst, the way that later in the summer she would jump into the deep end of the neighborhood pool without knowing how to swim. She had to be fished out by lifeguards. When she fell for something she loved, she fell hard and fast. All across the school year in our weekly afterschool class, I had struggled to find books that wouldn’t provoke the word that Elizabeth hauled out for things she didn’t love: boring. It had been a rocky year for Elizabeth and for me, but now I was hopeful that Elizabeth could find herself on the pages of a novel about a working-class girl’s life. It was the very novel I would have wanted as a girl her age, a girl without a teacher like me who would struggle with a choice so simple—the choice of a novel—and yet so important.

Elizabeth.

At 9:20 that morning, Elizabeth and I sat together on the colorful patchwork quilt, talking about the novel. We sat cross-legged on my old family quilt, and Elizabeth read a passage from the book’s first section, Fall, about one season in a year of big changes for Ellie Farley.

“She was a nervous woman with a nervous laugh.”

Elizabeth read aloud from a chapter entitled “At the Dinner Table.” A narrator’s voice conveys Ellie’s anxious feelings as she sits at the family dinner table. On the one hand, there are the “silences and secrets of four teenage girls”—Ellie’s sisters. Then there is Ellie’s mother, full of hurt and angry resignation.

Elizabeth read aloud from the scene: “And though she had been welcoming with her warm arms when the girls were all small, she had withdrawn those arms more and more as the girls grew. Now Ellie couldn’t remember the last time she had been hugged by her mother.”2

Elizabeth paused for a moment. The story made her think of the house where she lived.

Elizabeth’s family lived out Perry Avenue, past Blair’s house. To get there, you turned down a small side street that dead-ended in a cul-de-sac. Beyond Elizabeth’s home was an industrial park; to its right was a weedy, overgrown lot. Elizabeth’s family owned the house, but the lot next door belonged to a slumlord who sometimes used it as a dump for old cars. Elizabeth’s world the year she was ten was the small universe of a dead-end street and a rundown two-story house packed with nine young bodies. The only way in or out was by means of the green van that her dad drove, packing everyone in to drive to and from school or other required destinations. He was still working on and off, but the family was one of the poorer ones even in a neighborhood known for its hard living.

Elizabeth’s mother had family in nearby rural Indiana, and her grandmother still lived down there. Most Sundays, the kids were packed into the green van and driven across the state border to a small country church. Elizabeth would listen to the Sunday preaching, taking careful note of how the minister was eyeing the breasts of the teenage girls. Her mother had left the country at fourteen and had gotten pregnant with her first child. Now everyone was kept under the stern, watchful eye of Elizabeth’s father and—of course—the Lord Himself.

As she read, Elizabeth must have found herself connecting with many of the things happening to Ellie. Like Ellie, she shared a bedroom with four sisters. The youngest, little Julie, was still getting potty trained and sometimes wet their shared bed. As a matter of fact, Elizabeth thought that she herself smelled like pee this morning because of Julie. And like Ellie in the novel, Elizabeth could not remember the last time she had gotten a hug from her mother. Her mother, a woman in her thirties, was pregnant again and stressed out from trying to raise the nine children she already had.

Elizabeth looked to me, as if the realization had suddenly hit her.

“Hey, the girl in the book is just like me!” she said.

She seemed surprised at the threads of connection, but also excited—as though, I thought, she had stumbled upon an unexpected treasure, something that called to her as though it were meant to be hers, as she meandered through a junk store filled with dreary old relics.

Eureka! I thought. This is it!—the kind of moment I had dreamed about when I created a reading class for girls. Here was Elizabeth, a young reader who seemed to be in her literary element. She was making strong personal connections to a novel. She was engaged and active—reading the book with a questioning and curious spirit, going back and forth between the novel’s fictional portrayal of a girl’s life and her own life.

There was just one problem: Elizabeth didn’t like the book.

“I’m sure you’re all excited about reading,” I offered hopefully as we sat on my quilt later that morning, having one of our first book group discussions that summer.

“I’m not!” shot back Elizabeth.

The idea of reading a novel about a girl like her was one big reason she didn’t care for the book.

“It’s kind of stupid,” she remarked.

Elizabeth’s observation stung a little, but I was determined to move ahead. The time felt right to dig into a character-driven novel.

“Can some of you talk about how your life connects with Ellie’s life in A Blue-Eyed Daisy?”

In the meantime, Elizabeth had embarked on a different agenda: finding the few swear words that appeared on the novel’s pages.

“And she said a cuss word that says h-e-l-l,” Elizabeth said, thrilled with her discovery.

This was, I knew, a time in Elizabeth’s life when the word hell had strong meaning. On their Sunday jaunts to the country church where her mother’s cousin did his preaching, the girls in the family learned about being saved from going to Hell. Now it was hard to get her thoughts wrapped around the kinds of things I wanted to discuss.

“That is not a cuss word!” said Alicia.

“What about my question?” I said, with more firmness in my voice. I was starting to grow irritated, or maybe just a little hurt.

“There’s this boy that kissed her,” said Alicia. “Harold, his name was Harold.”

“Oh, my gosh!” said Elizabeth, her long arms making a tiny movement upward, like a young sparrow about to flap its growing wings.

The thing that meant the most to Elizabeth that summer was the door of friendship that had been opened to her by our group’s sweet-faced Alicia. Before this happened, Elizabeth didn’t have a best friend in school. She felt alone and disconnected in the world. At home were her eight siblings, ranging in age from a toddler in diapers to a girl in her teens, and Elizabeth’s stressed-out mother. But everything had changed with her discovery of a friendship that seemed fated to happen. One afternoon we had gone on a fieldtrip to a local bookstore so that each member of my class could pick out a book to call her own over the summer. Elizabeth chose an illustrated copy of The Secret Garden, and with the book came two necklaces with charms. It seemed only natural to her that one of the charms should go to Alicia.

“Like the book said, Ellie was getting kissed,” said Alicia. “And a long time ago when I was little there was this stupid idiot boy that tried to kiss me. I smacked him and punched him and told my mom. But he kept on doing it, so I kicked him and I kept on beating him up, and he finally stopped.”

Elizabeth said, “The only part that would’ve stopped him is to kick ’im where it hurts. That’s what I say.”

“No, you don’t do that,” said Alicia.

“Uh huh, I would do it,” said Elizabeth.

“Are there other ways that Ellie’s life experiences or her feelings connect with your life?” I asked.

Blair sat opposite Elizabeth and Alicia on our quilt. She thought about the bedroom she shared with her grandma, her little niece, and sometimes one of her half sisters. The teenage boys, her half brothers, came in and out of the room at night when they wanted to watch television, and this kept Blair awake. She could picture the room she wanted, with a big bed and Pooh Bears on the wall.

“Ellie’s life is like mine because she is sad all the time,” she said.

Alicia was still only nine, and she looked every bit the part of our group’s little girl. She had worked herself into a serious case of the giggles over the kissing scene in A Blue-Eyed Daisy. But when Blair spoke, Alicia’s face softened into an expression that seemed older.

“Why are you sad all the time?” she asked.

“Because I’m tired of sharing a room with my sisters,” said Blair. “And my dad—like she has a father that drinks a lot—my dad’s a drunk and a smart-aleck.”

I thought about the word that Blair used: dad. I had a hard time attaching it to the factual details of her biological father. He had been little more than a passing moment in her mother’s quest for alcohol, drugs, and, I suppose, love, to the extent that love could be distinguished from desperate need and desire. Every time Blair thought about the man she called Dad, she felt angry and confused.

“And he never stops drinking,” she said.

“If I was Ellie, and I had a father that drank and a mother that argued,” said Adriana, “I would call the police. Ellie needs better parents. Parents that are nice, that don’t get drunk and argue with each other.”

Adriana lowered her eyelids, as though her vision were turning inward. “I bet Ellie wants a nice house with absolute no parents and quiet and . . . and a big swimming pool. The reason I say that is that is what I need.”

I thought of the novel and its story about a girl who struggled for a relationship with her damaged and defeated father. “Is what you want different from what Ellie wants?” I said.

“I want it to be no parents,” Adriana replied. “And the reason is—I hardly get to see my real dad. He doesn’t come to see me because he’s too busy up his stepkids’ butt. My mom and stepdad argue all the time in front of me, which they’re not supposed to.”

Adriana let out a small laugh. “This one time my mom and my stepdad were arguing, and my mom threw the coffeemaker on my stepdad. And it broke.”

“My mom beats the crap out of my dad!” said Alicia in her young voice.

“My mom is like hers,” said Blair, looking sideways at Adriana, seated to her left. “Because her mom breaks things over her stepdad’s head, and my mom breaks telephones over my dad’s head.”

“What’s it like for you to read a book with a character who reminds you of yourself in certain ways?” I said. “What does it feel like when you’re reading?”

“Weird,” Blair replied.

“What does weird mean?”

“Crazy,” she said, as if this second word explained everything.

“Why do you want us to read all boring books?” said Elizabeth. She had been unusually quiet during our discussion. Now she seemed downright sulky. And there it was again, the word that Elizabeth loved to throw out at such moments.

“Well, they don’t seem boring to me,” I confessed.

“I know, that’s the problem,” shot back Elizabeth. She had come alive again within our group. Her hazel eyes flashed; her long, skinny torso straightened upward.

I started to explain: “It’s hard for me to understand what you like because—”

“We don’t want your kind,” said Elizabeth, before I could finish my thought.

It was my kind of book she didn’t want. And there was a reason for this: my sentimental novel about a girl’s coming of age couldn’t hold a candle to the paperback that Elizabeth and her best friend, Alicia, had discovered on their own.

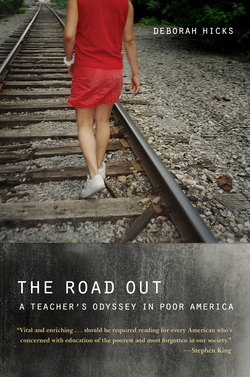

It was found in a cardboard box of paperback giveaways, donated by someone from outside the girls’ community. From the moment Elizabeth discovered the book, she knew it was meant to be hers. The Final Nightmare was an old-fashioned ghost story, the third in the House on Cherry Street series about a summer rental house with a dark past. In the stories—written by the husband-and-wife team, Rodman Philbrick and Lynn Harnett—eleven-year-old Jason, his mom and dad, and his four-year-old sister Sally moved into an old gabled house for the summer. Almost right away, the house began to assert its haunted nature.

The spirits haunting the house revealed themselves only to Jason and Sally—the children. This was in part because at the book’s narrative center was the ghost of a child, Bobby, who had died when an evil nanny, Miss Everett, chased him with such malice that he crashed through a second-floor banister and fell to his death. The nanny’s spirit still reigned as an evil witch. Little Bobby also roamed the house, his child-voice aimed mostly at young Sally.

The morning following my attempt to lead the book group, Elizabeth and Alicia lay sprawled on the carpet with pillows to cushion their elbows. In front of them on the floor was the paperback with its torn front cover. The two girls took turns reading pages, though Elizabeth read faster. She read aloud like she spoke—fast and with an edgy tone in her voice. Alicia listened closely. Young Jason had gone upstairs to the attic to investigate some inexplicable things about the summer house on Cherry Street.

I stepped into the attic.

I gasped in surprise. And instantly bent over coughing as the dust flowed down my throat. But I didn’t care.

The attic was a wreck!

The walls were totally smashed in. There were big holes in the floor.

And Bobby’s rocking chair was still there!

The little rocking chair was the only thing that wasn’t smashed to bits—everything else was broken or damaged.

Even my parents would have to believe the house was really haunted when they saw this!

I was about to yell for my dad. Then I heard something move behind me. A rustling, sneaky sound in the shadows.

The back of my neck tingled.

I was slowly turning around to look when a horrible voice spoke right by my ear. A creaky, raspy voice of the undead.

“You!” it shrieked. “It’s all your fault! I’ll get you! I’ll get you for good!”3

It was not surprising to me that Alicia chose to read the paperback book that she and Elizabeth had discovered in the box of secondhand giveaways. Alicia had lost crucial ground in reading that year. Near the end of the summer before, just months before she was to enter fourth grade, Alicia moved across the river to Kentucky. There was some hint of family trouble, but none of this was spelled out for teachers such as me. Later I would be able to fill in some of the pieces—the street drugs, her mother’s falling out with an older churchgoing generation, the desperate need for housing. But mostly what I saw were their effects. In late spring of the school year, Alicia had moved back to Cincinnati, looking lost and reading far behind peers such as Elizabeth. The Final Nightmare was at just her reading level, and she read even its fast-paced action and campy dialogue slowly—word by word.

Elizabeth was in a different place. She was already a stronger reader, and she had been part of my weekly class during the school year. Across the school year she had changed so much as a reader that I knew that summer reading could be a turning point for her. Also, I felt a teacher’s sense of urgency, because already Elizabeth was beginning to lose her attachment to school. This was strange and troubling to me, because earlier that same year she had started to find herself in the world of books.

The previous winter, when our ritual of talking about fiction was interrupted by the clang and hiss of an old radiator letting out its steamy heat, I had decided to introduce Kate DiCamillo’s sweetly moving and sentimental novel Because of Winn-Dixie.4 Set in a working-class locale in rural Florida, the novel featured themes familiar to Elizabeth. Its young heroine, India Opal, lived with her single dad in a trailer. India Opal was motherless and she felt alone, but her fate changed one day when she befriended a mangy dog in the local Winn Dixie grocery store.

Until then, Elizabeth had been all resistance to the strange notion of reading about a fictional character whose life echoed her own. But things changed for her with this new novel, and once she got into it she couldn’t put the book down. She gave the book a rating of five stars, the highest number possible. Elizabeth was starting to feel differently about reading. She was beginning to realize that she could be a girl who enjoyed books.

“I'm the only one in my family who likes school,” Elizabeth remarked one February afternoon in my afterschool class for the girls.

Once she knew what her heart wanted, Elizabeth was not a girl to be easily deterred.

But in Elizabeth's regular language arts classroom, another kind of change was stirring. Earlier that year the girls had spent up to an hour each day reading books that I helped acquire for their morning instruction. Now reading literature had been overshadowed by practice sessions for the end-of-grade test. In March, the students would take their yearly proficiency test; fourth grade was a benchmark year. Everything seemed to ride this one performance. Teachers would be judged on the results. Students would be deemed proficient or not, though no one seemed sure what this would mean in terms of retention. One thing was known: Failure to achieve a proficient score in reading would result in a recommendation for remedial summer school classes. None of the girls wanted to have the dreaded letter sent home.

Boredom was a feeling that Elizabeth knew well, but now her boredom seemed tethered to an even stronger feeling: anger. One morning in late February, Elizabeth sat fuming over the latest practice test. The theme for the morning's run-through was Johnny Appleseed, a topic that could just as easily have been plucked out of one of my schoolgirl workbooks. The story was stupid, Elizabeth felt. The students in her class had been given a reading selection about Johnny Appleseed. First they had been asked to compose a journal entry, “Your Day as Johnny Appleseed.” Now they were being asked to write a factual report based on the reading selection.

“This is boring,” Elizabeth said as she confronted the paper in front of her. “This sucks,” she added, her rage threatening to unhinge her. She found the whole thing maddening, but the exercise was still casting its shadows of uncertainty. Her worst fears were confirmed when she got her paper back, red-inked with the ominous words: Not Passing. Elizabeth exploded. She wrote STUPID in bold, oversized letters, leaving her own mark on the idiot report. Inwardly, she was beginning to have doubts that she could make it through the needle's eye of the March test.

In January 2002, the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act had been signed, cementing the effects of an accountability movement that was already sweeping through public schools across America. Nothing in the bill spoke to the role of literature in the teaching of reading. In fact, the language of NCLB made testing, not curriculum, the new mantra of education. “Measurement is the gateway to success,” said President George W. Bush, of the bill he made a centerpiece of national educational reform. The narrowing of the curriculum was an unintended consequence, the effect of trying to reduce complex and imaginative thinking about books to a single-shot test with multiple–choice answers. Teachers in the poorer schools found themselves scrambling to get their students to bubble in the right choices, something that came naturally to students who had grown up with parents talking to them about books. Students such as Elizabeth were novices; they had more trouble figuring out the language game of the test. What Elizabeth truly needed was guidance in the basic process of finding herself in books that featured richly developed characters and literary themes. But this kind of teaching was becoming harder and harder to justify, because it was difficult to quantify in scientific terms.

“There's something wrong with me” was Elizabeth's understanding of the whole testing business.

A paradox was starting to reveal itself to me, and it had to do with the ways that reading was swept into the currents of the accountability movement. The rhetoric of the accountability movement in public schools was all about change. But from what I could see from my vantage point as a teacher, little had changed since my days in a school serving the children of North Carolina factory workers and farmers. The accountability movement had frozen into place the same inequalities that shaped my experiences in school. If anything, students like Elizabeth, those who could most benefit from reading novels and talking about literature, were now even more unlikely ever to get that kind of rich liberal arts education. For her, the pervasive focus on test preparation was squeezing out a nascent love for books and learning that could have helped her achieve the success that everyone wanted. It was not fair to Elizabeth, who had taken the first quivering steps toward becoming a real reader. So when summer came, I was even more determined to help her find her way into a work of fiction about a girl's life. It didn't occur to me that she had already found herself in a book, and that it wasn't my book—or my kind of book.

Again and again in the evenings of that summer, confused and exhausted after the day of teaching, I returned to the question of why Elizabeth, Alicia, Blair, and so many of my girls were so much in love with their stories of ghosts and horror. A small literary movement was occurring in my summer class, in subtle ways that, when added together, created a collective feeling for books. Adriana's mother still had the copy of Pet Sematary that her Grandma Fay had lent her, just before she died. On a slow, warm night that summer, Adriana had watched the movie with her mother—for the third time. Elizabeth got to watch the occasional scary movie in her crowded living room, after she helped put the youngest to bed. Blair sat up late into the night, listening to her half sister read from the Stephen King books she bought at Walmart. Adriana felt certain that the basement of her apartment building was haunted. A girl had been raped down there. And Alicia was sure that there was a real ghost in her grandmother's house, for the young man who had once lived there had shot himself.

The young girls in my reading class were not alone. Horror fiction had become rampant in popular culture, so much so that parents and teachers had begun to voice concern about the images of maiming and psychopathic mayhem flooding the popular book and movie market. These movies—Final Destination, The House of 1,000 Corpses, Slash, 13 Ghosts—were geared to a ravenous audience of horror fans, many of them still in their teens. Such trends had led to a flurry of writing about the subject by literary and film critics, cultural scholars, and even psychoanalysts.

One explanation offered for the feeling that my girls experienced when reading scary books is the notion of a psychic safety valve. Fans of horror and ghost stories can experience a thrilling read, and yet know that in the end they will be safe. This can be cathartic—like screaming bloody murder on a roller coaster ride, then walking off with tears of laughter streaming down your face.

But this wasn't the only explanation for the strange appeal of horror. Every reader of fiction searches for the threads that can connect her inner life to the landscape she inherits. And these threads of connections need not be real—or not something you can see or touch in the everyday world. Fiction's special appeal is that it can take us out of this world and help us connect with what can only be seen through the imagination's inner eye. Part of the beauty of ghost stories was that they were not real. Crazy, weird, and Elizabeth's favorite word, boring—this is how my students felt about reading a realistic novel. The gray world of ghosts and horror stories felt more familiar and strangely, more soothing, than the harsh light of a realistic novel.

Elizabeth wasn't yet ready for novel about a girl who was “just like her.” Could I bring myself to enjoy the kind of book that she loved?

Later on the morning of June 27, I sat with Elizabeth on my family quilt, and we talked about books. By that time, the temperature inside our borrowed summer classroom had started to rise. The late morning air felt heavy and wet with humidity. The toxic-smelling fumes from upstairs were getting to me. By eleven that morning I was already feeling exhausted and confused about how I should work with Elizabeth. But curiosity—a desire to understand what I don't know—was always one of my strongest motivations as a teacher. So I tried to get to the bottom of Elizabeth's feelings about reading. Like everything else, she was passionate about her books.

“So do you like to read?” I asked Elizabeth, who was looking smug, like a young queen on a royal carpet.

“Heck, yeah. Whoo!” replied Elizabeth.

It wasn't exactly the response I had expected. Since our book group discussion earlier that morning, Elizabeth had seemed lost in a preteen sulk.

I probed a little further: “What books do you think we could read in our summer class?”

“The books you're going to order—NOW!”

I knew exactly which books Elizabeth meant: the House on Cherry Street series. Elizabeth was as stubbornly committed as any girl could be to reading the ghost stories.

“And what else?” I asked, still hoping to plant seeds for the kind of literature I preferred, such as A Blue-Eyed Daisy.

“Zip!” she replied.

The House on Cherry Street books were out of print but available on Amazon at cheap prices—as low as a dollar each. I sat down that night at my computer and ordered as many cheap copies as I could find. It was a small gesture on my part, but word spread quickly. Maybe summer reading wouldn't be so boring after all. It was clear what Elizabeth wanted to read, and engagement of any kind seemed more urgent than my concerns that the girls’ paperbacks were less character-driven or literary than my novels. I was starting to lose Elizabeth, and she was only ten years old. Where would we be years from now, in adolescence, if she could not form a stronger attachment to school? It was time for Elizabeth to find herself once again in books, even if it was the improbable world of ghost stories and horror fiction that took her there.