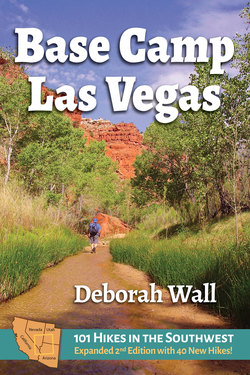

Читать книгу Base Camp Las Vegas - Deborah Wall - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеRock Rock Canyon National Conservation Area

Looking toward the Calico Hills in Red Rock Canyon. Yucca, Joshua trees, and creosote coexist in this natural landscape.

Visitors to Southern Nevada are often surprised and delighted to learn that just outside one of the most bustling cities in the world, they can easily experience such a dramatically different landscape as Red Rock Canyon. Only seventeen miles west of the teeming and intentionally artificial Las Vegas Strip is a stunning display of natural beauty, offering pockets of solitude to those who seek it. If you don’t live here or are a newcomer, not yet familiar with how lovely the outdoor West can be, Red Rock Canyon is where you should start to find out.

Tucked into the eastern edge of the Spring Mountain Range, this is a land of red sandstone and gray limestone formations, amid open landscapes, narrow canyons, mountains, and springs. The park gets about six to ten inches of moisture a year although nearby Las Vegas usually gets only three to four inches. The canyon is moist enough to host eight major plant communities, which support a generous variety of wildlife.

Here are more than six hundred varieties of plants and three hundred of animals. Look for desert bighorn sheep in the rocky and steep terrain, mule deer in the foothills and even burros as you travel along the lower-elevation trails and roads. Gray foxes, coyotes, mountain lions, and desert tortoises also live here.

Fragile and non-renewable evidence of American Indian occupation, in both historic and prehistoric times, has been protected here. There are wonderful examples of agave-roasting pits, petroglyphs, and pictographs.

October through April is the best time to hit the trails. Summer’s high temperatures can be unbearable unless you start (and finish) the trail first thing in the morning. There are no services in the park, but gasoline, convenience stores, and restaurants are available on West Charleston Boulevard, less than half an hour from the park’s entrance.

In 1990 the area was officially designated Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area; administered by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), the park contains close to two hundred thousand acres.

The BLM has designated the park’s thirteen-mile, paved, one-way scenic drive as a Backcountry Byway, recognizing its unusual level of beauty and interest. Most of the trailheads mentioned in this book are located along the byway, and are reserved for day use, which means the hours change according to the season. In October “day use” means 6 a.m.–7 p.m.; November-February, 6 a.m–5 p.m.; March, 6 a.m.–7 p.m.; April–September, 6 a.m.–8 p.m. The Red Rock Canyon Visitor Center is generally open 8 a.m.–4:30 p.m. daily. For visitor information: (702) 515-5350, or www.redrockcanyonlv.org.

Directions: From Las Vegas take Charleston Boulevard (Nevada Route 159) west. From its intersection with CC 215 (Las Vegas Beltway), continue west 5.8 miles and turn right for entrance station and Red Rock Canyon Visitor Center.

1 Calico Basin—Red Spring Interpretive Trail

Calico Basin offers a mixed grill of the Red Rock area’s best, including riparian habitat, meadows, springs, and even some cultural resources, all within the area’s signature Aztec sandstone landscape.

An easy way to taste it all is to take the Red Spring Interpretive Trail, which starts directly behind the picnic area. This will take you up a small rise and to the grassy bench above. From here the trail makes a one-half-mile loop around the perimeter of the meadow. This trail is accessible for wheelchairs and baby strollers.

A boardwalk was installed in 2005 as part of a restoration project to protect the environmentally sensitive areas. This way, visitors can still enjoy the area without disturbing the fragile plant life. Outside the boardwalk there is a fence to keep burros and horses from trampling these areas.

Calico Basin; A boardwalk was installed in 2005 to protect the Red Spring surroundings from being trampled.

As you travel along the boardwalk, stop and read the interpretive signs. Be sure and take time to sit quietly a while on one of the many benches along the way, listening and looking for wildlife. Because of a permanent supply of water, lush vegetation, and surrounding canyons, many animals thrive here. More than one hundred species of birds have been recorded, and the area is also home to mountain lions, kit foxes, coyotes, rabbits, ground squirrels, desert tortoises, and ringtail cats. I even had the good fortune of seeing a gray fox on one early-morning visit.

There are three springs in this vicinity. Ash Spring, Calico Spring and Red Spring provided reliable and vital water sources to humans for thousands of years. American Indians used this area and were followed by homesteaders and ranchers. As you make your way around the walkway and over to the sandstone cliffs, keep an eye out for rock art. There are two types in Red Rock Canyon, petroglyphs and pictographs. Here you will be seeing petroglyphs which have been pecked into the surface of rock, unlike pictographs, which were painted on the surface. Some of this rock art is thought to be more than five thousand years old.

Once you reach the far end of the boardwalk from where you started, you will see the waters of Red Spring itself, flowing from a small tunnel or cave. If you look carefully you will see many water-loving plants such as the stream orchid, watercress, Nevada blue-eyed grass and black-creeper sedge. The boardwalk protects not only these plants but also local inhabitants such as red-spotted toads and Pacific chorus frogs.

A few biologically sensitive species also call this area home. The Spring Mountain springsnail, Pyrgulopsis deaconi, is found only in four springs, all of them nearby. The alkali Mariposa lily, which grows in the surrounding riparian meadow, is found only in a few other places in Southern California and Nevada. The largest population in Nevada is said to be the one here.

If you visited this area before the boardwalk was installed, you might remember being able to drive almost up to the base of Red Spring, and park there. As you travel along the boardwalk it’s worth a look in that area to see how it has been transformed. The old road has been covered over and replaced with native vegetation. It’s on its way to restoration as original habitat.

Although this is an excellent place to go when your time is constrained, there are hiking trails just outside of the boardwalk area that are well worth exploring when you have more leisure. There is also a picnic area, with restrooms.

Calico Basin—Red Spring At A Glance

Best season: October–April.

Length: One-half-mile loop.

Difficulty: Easy boardwalk.

Elevation gain: Minimal.

Trailhead elevation: Thirty-six hundred feet.

Jurisdiction: Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area.

Directions: From Red Rock Canyon’s main entrance drive east on Charleston Boulevard (Nevada Route 159) for 1.4 miles. Go left onto Calico Basin Drive and drive about one mile to the signed parking area and trailhead.

2 Calico Tanks Trail

The main attraction of the Calico Tanks Trail is a large tinaja — a natural waterhole or tank weathered into native rock. But the whole hike is interesting, taking you through a vegetated canyon within a white-and-red sandstone landscape.

Unless you arrive first thing in the morning you will probably find dozens of cars in the parking area. Although the hike is one of the most popular in the park, those cars did not all bring visitors to the tank. The parking lot also serves as the trailhead for Turtlehead Peak, and this is a popular area for rock climbers as well. It is also a favorite for those who come just to take a short and easy stroll around the colorful formations, and perhaps see the remnants of a historic sandstone quarry and an agave-roasting pit.

From the parking area head north along the wide and obvious trail. After about 140 yards you will want to head left across a wash, but first it’s worth a look about twenty yards ahead at the large, square blocks of sandstone, said to weigh ten tons each. These are remnants from the quarry that operated here from 1905 to 1912.

After examining the blocks, backtrack and resume the main trail, swinging to the left of the blocks, which will take you down and over a usually dry wash. Start looking on your left for the BLM sign that marks an agave-roasting pit just a few yards off the trail. The hearts of agave, a kind of yucca which still grows hereabout, were a food highly prized by American Indians up to modern times. Continue north until you see the sign marking the right-hand turn for the Calico Tanks Trail.

Follow this spur trail which will take you up a small drainage surrounded by scrub oak, manzanita, and pinyon pines. If you take this hike in late March or early April you might be treated to the showy, bright pink bloom of the western redbud, a small tree that is a member of the pea family. There are only a handful in the canyon but they are a spectacular sight to see.

This hike is a good one for all ages except young children. There is cliff exposure in a few areas, while uneven terrain and elevation gain make it is too strenuous for little ones. Most of the trail is exposed to the sun, so this can be a warm walk, but there is shade to be found along the route, except at the tank itself. Along the way look off to the side of the trail, for areas with fine sand that captures the tracks of chipmunks and birds.

A hiker takes a break to admire the Calico Tanks.

As you continue up the canyon in the steeper sections, you will find hand-placed sandstone steps. There are a few areas you will need to do some route finding but it would be hard to get lost, for the right way is always up the main canyon.

The water level in the tank fluctuates greatly depending on rainfall. I have never found it completely dry, though I have never been there in summer. There is plenty of room to walk around the sandstone shoreline to the left, which affords a comfortable place to sit by water’s edge. Be careful traversing the slope, though, for I have seen people lose their footing and slide in.

Another reason to watch your step is to preserve the easily damaged shoots of water-loving vegetation, especially in springtime and on the south shore. This waterhole is critical to the survival of the park’s wildlife, but not good for humans; don’t drink it or enter the pond.

Seasoned hikers looking for more adventure can head to the southeast corner of the pond and scramble twenty feet or so up a sandstone cliff. From here you can see the visitor center and the first parking area of the Calico Hills, which you passed on the way to the trailhead. If you travel farther, you can even get good, far-reaching views of Las Vegas. There are plenty of high drop-offs in this area, so only those who are sure-footed should hike here.

Calico Tanks At A Glance

Best season: October–April.

Length: 2.5 miles roundtrip.

Difficulty: Moderate.

Elevation gain: 450 feet.

Trailhead elevation: 4,310 feet.

Warnings: Cliff exposure, rock scrambling.

Jurisdiction: Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area.

Directions: From Red Rock Canyon’s main entrance, drive about 2.6 miles on the 13-mile Scenic Drive to the Sandstone Quarry parking area on right.

3 White Rock Hills/La Madre Spring Loop

This circle will take you around the perimeter of the White Rock Hills with excellent views of the surrounding La Madre Mountains. You’ll see several agave-roasting pits and possibly bighorn sheep.

Furthermore, it’s an unusually versatile trail with the opportunity for side trips to several springs. The entire loop is a bit long for children but there are no dangerous drop-offs if you stick to the main trail. Since it’s a loop hike you can start in either direction but I recommend counterclockwise, which feels a little less strenuous because you’ll encounter most elevation gain early in the hike, while you are still fresh.

From the signed trailhead, walk north. Look on your left, up a small rise, for a roasting pit. Little more than a century ago American Indians still used such pits to cook the hearts of agave plants, which grow in the surrounding hills and are marked by tall flowering stalks. Unfortunately this pit isn’t well defined because people have trampled on it, but you can still see the faint mound shape, and the blackened rock and ash on the ground. This hiking route passes several more roasting pits in the Willow Springs area.

The trail is well worn and easy to follow except in a few places during the first one-half mile where it crosses a few small washes. Ordinarily there are obvious paths across the drainages, but after a heavy rain or flood you might have to scout upstream to find the trail on the other side.

Along the trail you will be in a pinyon-juniper plant community which includes scrub oak, Mormon tea, manzanita, Mojave yucca, and prickly pear cactus. In spring you’ll see wildflowers. Keep an eye out for scrub jays and rock wrens.

From the trailhead it is a steady ascent of about 590 feet over about a mile and one-third, to a saddle, which marks the highest elevation of the hike. Vegetation becomes dense compared to that around the trailhead; up here pinyon pines and junipers grow higher than a person’s head, and even provide some shade.

At the saddle you will find a spur trail on your left, marked by a cairn. Sure-footed adults willing to do some rock scrambling can take this path up the sandstone bluff to points commanding spectacular views of the La Madre Mountain range to the north and west. These are great places to take a break and enjoy a snack, giving you more time to take in the views. Bighorn sheep frequent this area, so be on the lookout for movement in the steep parts of the landscape.

The White Rock Hills route takes hikers through a pinyon-juniper plant community which also includes Mojave yucca and prickly pear cactus.

Once you backtrack down the spur to the saddle, the trail gradually descends into La Madre Spring Valley and the west side of the White Rock Hills. After about one and one-half miles you will reach a junction where the route turns left onto an old gravel road. But for an excellent side trip, go right instead, and follow the road less than a mile to La Madre Spring, which flows perennially.

The spring feeds a shallow pond, about the size of a large, portable wading pool, which was created by a dam built in the 1960s. Surrounded by Baltic rush, bulrush, reeds and other water-loving plants, it is beloved by area wildlife including bighorn sheep and mule deer. You can sometimes see them of a morning or evening.

If you’re skipping the side trip, or after returning from it to the junction, follow the old road about one-half mile to Rocky Gap Road — main route to Pahrump in days of yore — and go left. Continue down the gravel road for about one-half mile to the Willow Springs Picnic Area.

A little below the parking area, look for the sign marking the point where the trail leaves the road and heads east. A little more than two miles farther along, you’ll see another spur trail on your left that brings you down to White Rock Spring. There is a bench where you can relax, watch for wildlife and listen for birds before heading up the trail a mere one-tenth mile to the parking area where you started. That’s one of the nicest and most unusual features of this hike. How many other opportunities are there to hike six miles, yet end the hike well rested?

White Rock Hills/La Madre Spring Loop At A Glance

Best Season: October–April.

Length: Six-mile loop.

Difficulty: Moderate.

Elevation gain: 885 feet.

Trailhead elevation: 4,875 feet if starting at upper White Rock Spring Trailhead.

Warning: Flash flood potential in washes.

Jurisdiction: Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area.

Directions: From Red Rock Canyon’s main entrance, follow the 13-mile Scenic Drive for 5.7 miles and go right. Follow this access road 0.5 miles to parking area. The trailhead for doing the loop in a counterclockwise direction is on the north side of the parking area.

4 La Madre Spring Trail

This route takes you directly to a perennially flowing, spring-fed stream and a small pond, manmade in the 1960s. Although many visit this spring as a side trip from the White Hills Loop Trail, this is a different, shorter route through sandstone and limestone hills.

It’s a good hike for children, with no drop-offs or obstacles along the main route. Very young hikers, though, might struggle keeping balance on the uneven, rocky surfaces. And because it’s very rocky in places, everybody will be more comfortable in sturdy-soled hiking boots instead of lighter-tread sneakers or trail-running shoes.

From the Willow Springs Picnic Area, which serves as the main parking area for this hike, walk up the rough, gravel Rocky Gap Road. This road was once called the old Pahrump Highway or the Potato Road, and was a major route to Pahrump for about fifty years starting in the early 1900s.

After one-half mile you will cross Red Rock Wash (usually dry, but a major drainage). After crossing the wash continue up the road about 130 yards and you will see the sign that marks the official La Madre Spring trailhead on your right.

From the signed trailhead head up the now-abandoned jeep road which will bring you high on the west bank of Red Rock Wash. You will be in a pinyon-juniper plant community which in this area includes scrub oak, Mormon tea, sagebrush, manzanita, Mojave yucca and prickly pear cactus.

About one-half mile after leaving Rocky Gap Road you will come to a signed junction. To the right is the White Rock Loop Trail that circles north around the White Rock Hills and back to the Willow Springs Picnic Area, about six miles in total. For the La Madre Spring hike, however, you continue straight ahead.

Travel about three-tenths miles farther and you will see an obvious and wide spur trail on the right. This fifty-yard side trip takes you to an old house foundation. I paced it out to be about fifty-five by thirty feet. There are still some remains of the old floor tile; very strong glue has held it in place through about four decades of desert heat and cold.

Off the main trail there is another short spur trail on the left where you can find another foundation about the same size.

Continuing up the main route about four-tenths miles you will arrive at the official end of the trail, marked by an interpretive sign. From here look down the embankment and you will see the pond and dam surrounded by Baltic rush, bulrush and other water-loving plants. La Madre Spring itself is located upstream.

A small dam creates a little pond, a haven for water loving plants. This area is frequented by mule deer and desert bighorn sheep in early mornings and evenings. La Madre Spring is upstream.

This is a lovely place to have lunch or just relax on the wide flat areas and listen for birds. Desert bighorn sheep and mule deer are often seen here in mornings and evenings.

Although this ends the official hike you can continue upstream on a well-worn, yet narrow path within a pretty canyon, and about one-half-mile farther will come to the remains of an old miner’s cabin. This area was privately owned until 1975 when the Bureau of Land Management acquired it.

Along the way you will have to do many stream crossings but need not get wet, for the stream is usually only a couple of feet wide. The most pleasant part of hiking upstream is the sound of the water as it flows through the constricted drainage under a thick, low canopy of vegetation.

La Madre Spring Trail At A Glance

Best season: October–April.

Length: 3.6 miles roundtrip from Willow Springs Picnic Area.

Difficulty: Moderate.

Elevation gain: 715 feet.

Trailhead elevation: 4,580 at Willow Springs Picnic Area or 4,804 at official trailhead.

Warning: Flash flood danger.

Jurisdiction: Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area.

Directions: From Red Rock Canyon’s main entrance, take the 13-mile Scenic Loop Drive for about 7.5 miles. Go right and drive 0.6 miles, parking on the right at Willow Springs Picnic Area. If you have a high-clearance, four-wheel-drive vehicle you can drive 0.6 miles farther to the official trailhead.

5 Children’s Discovery Trail and Lost Creek

This is a loop trail with the opportunity to take a short side trip to a seasonal waterfall in Lost Creek Canyon. Besides the waterfall, it accesses a creek, an agave-roasting pit, pictographs made by American Indians, and interesting plant life. With appealing elements for adults and children alike, it makes an ideal introductory hike.

The trip is easy but one must actually hike. Strollers and little ones’ legs don’t work well here because of uneven, rocky terrain, sandstone steps, stream crossings and slippery rocks near the water. Small children need to be in a child-carrier pack of some sort.

From the parking area, take the trail at the far right, well marked as the Children’s Discovery Trail. After less than five minutes you will cross the broad Red Rock Wash. This is usually a dry stream, but if you happen to find a good flow of water here, or even if it rains when you visit, save this hike for another day. This wash is a major drainage, so flash flooding is common, and it is possible to walk across the wash dry-footed, yet be unable to return safely just a few minutes later.

On the other side of the wash, the trail narrows and begins an easy ascent up rocky terrain interspersed with smooth sandstone steps, into a plant community of manzanita, shrub live oak, juniper, and pinyon pines.

For the next quarter-mile the area contains important cultural resources — fragile and non-renewable evidence of prehistoric occupation. This area is known to have provided a seasonal camp for American Indians.

Look for the sign indicating the location of an agave-roasting pit, sometimes called a prehistoric kitchen, near a large pinyon pine. The native people created such pits by burying the basketball-sized hearts of the agave plant, along with rocks heated in a fire, which cooked this favorite food slowly and thoroughly. Vanishing elsewhere, the pits are still common around Red Rock Canyon.

You will find a signed spur trail on the right, to Willow Springs Picnic Area; the side trip is less than a mile one way. Continuing on the main loop, on your right you will notice sandstone cliffs that have many overhangs. Keep an eye out above and around these because sometimes you can see desert bighorn sheep, especially in the early morning.

There also are a few pictographs in this area. They are very faint so it might take you a while to spot them. But they’re worth looking for, as pictographs are not common in our area. Unlike petroglyphs, the more common but equally irreplaceable form of rock writing, pictographs are painted. Pictographs tend to weather away, and both kinds are easily damaged by the touch of human hands, boots, etc.

About one half-mile from the trailhead take the unmarked spur trail on your right, towards narrow Lost Creek Canyon. You will need to make a couple of minor crossings over the creek. The trail also passes by a ponderosa tree, an unusual sight at this relatively low elevation. Because of the water and cooler temperature, a handful of ponderosas grow not only here but also in nearby Pine Creek Canyon. If you are unsure which of the large pines are ponderosas, smell the bark; its scent resembles that of vanilla.

Continue up the sandstone steps, which will bring you under the wedge where two giant boulders have fallen against each other, forming a roof over the trail for a few feet. The trail ends about fifteen yards from here inside a box canyon, highlighted by Lost Creek Falls. About fifty feet high, the falls are seasonal; the best time to see them is usually January through March.

On your return from Lost Creek Falls side trail, continue down the Discovery Trail and you will come to a wooden boardwalk. This walkway and deck serve a higher purpose than merely keeping your feet dry. This is a riparian restoration area, and the boardwalk protects all sorts of plants from getting trampled, including wild grapes, horsetails, watercress, grasses and rushes. It also protects critical habitat for the southeastern Nevada springsnail.

From the viewing deck you can see Lost Creek as it flows under the willows, which form a broad canopy over the creek. Benches are built into the walkway, making this a good place to stop for a while and listen to the gentle sounds of the creek and the local birds, who like this spot as much as we do.

Children’s Discovery Trail At A Glance

Best season: October–April.

Length: 0.75-mile loop.

Difficulty: Easy to moderate.

Elevation gain: Two hundred feet.

Trailhead elevation: 4,460 feet.

Warnings: Flash flooding, uneven footing along rocky trail.

Jurisdiction: Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area.

Directions: From Red Rock Canyon’s main entrance, take the 13-mile Scenic Drive for about 7.5 miles and go right toward Willow Springs Picnic Area. Drive 0.2 miles and park on left at signed trailhead.

6 Ice Box Canyon

Ice Box Canyon is always picturesque, especially from January through March when you’ll probably see the seasonal show of cascades, deep pockets of water, and possibly waterfalls among the colorful sandstone bluffs.

Of course, the moisture that makes those months so agreeable also brings the danger of flash flooding. On any canyon hike, get an up-to-date weather forecast before hitting the trail.

Although it’s up to you how far you travel within the canyon, officially it is a two-and-one-half mile roundtrip with an elevation gain of a few hundred feet. You will encounter rocky and slippery terrain, so hiking boots with good treads and ankle support, never a bad idea, are especially in order here.

From the trailhead take the signed path and within minutes you will reach Red Rock Wash, a major drainage. The wash is about sixty yards across and during or directly after rain, can become a raging torrent. If rain threatens, yet the wash looks dry, do not be tempted to cross, for you might not be able to return safely if the weather isn’t bluffing.

As you make your way across the drainage, look for the sandstone steps on the far side, which will take you up onto the natural bench. Travel along the obvious trail and after about two-tenths miles from the trailhead you will come to a signed junction. The trail to the right is called the Spring Mountain Youth Camp Trail, though the camp is now located elsewhere. It leads hikers over to the Lost Creek area. The one going left is Dale’s Trail which leads to the Pine Creek area. For the Ice Box Canyon hike head straight, toward the mouth of the canyon.

As you continue you will find a plant community of scrub oak, desert willow, pinyon pine, and manzanita. There are quite a few social trails along the way, which can be confusing, but staying on the most-worn path and continuing up canyon will take you where you need to go. Some spur trails lead to the base of the steep cliffs and are used primarily by rock climbers. There are more than seventy climbing routes in this canyon alone, and more than two thousand in the park.

You might see white-tailed antelope squirrels, cottontails, jackrabbits, kit foxes, coyotes, or even a bobcat on this hike. Once inside the canyon look along the walls and you might see desert bighorn sheep. Birds here include Gambel’s quail, mourning doves, white-throated swifts, and cactus wrens.

After about one mile the trail descends steeply into the boulder-filled drainage, which will serve as your route if you choose to continue. But this makes a good turnaround point if you have children along or others unprepared for some difficult rock scrambling. Those up to the task will not only get a good workout but also drink great gulps of the canyon’s beauty.

It is a jumble of color with different-textured rocks from rough and jagged to slippery and water worn. There is no ideal route and you will have to find what works best for you. Be aware that many rock scramblers fall to their deaths each year. The most useful rule to avoid being one such is remembering that it’s easier to go up a given slope than to descend safely. Before going up, figure out how to come down.

Excellent rock scrambling skills can get you into Ice Box Canyon’s upper reaches. A hiker is seen on a high cliff.

Ice Box Canyon At A Glance

Best season: October–April.

Length: 2.6 miles roundtrip.

Difficulty: Moderate.

Elevation gain: Three hundred feet.

Trailhead elevation: 4,285 feet.

Warnings: Rock scrambling in canyon. Flash flooding.

Jurisdiction: Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area.

Directions: From Red Rock Canyon’s main entrance, take the 13-mile Scenic Drive about 8 miles to the well-signed trailhead, located on the right.

7 Pine Creek Canyon

Pine Creek Canyon has much to offer a desert hiker, including a seasonally flowing creek, the remains of a homestead from the 1920s, dense vegetation, and plenty of opportunities to explore the upper canyon.

Children who can handle the distance will like this hike, but there are drop-offs in one segment. I wouldn’t recommend allowing them into the upper reaches, because that requires too much rock scrambling.

From the parking area follow the well-defined trail south, down the bank and into Pine Creek Wash. Here the plants include blackbrush, Mojave yucca, and cholla cactus. The trail then heads west toward the escarpment, and soon scrub oak, willow, and juniper join the habitat.

Look closely within the juniper trees and you will find plenty of desert mistletoe, a parasite with scale-like leaves and berries. Although the plant sucks nutrients and water from the host plant, sometimes killing it, the berries are a treat for some birds, especially the phainopepla.

To the south you will see the tops of trees marking Pine Creek itself. It’s worth taking one of the many spur trails that lead over to its banks. Here you will find a riparian habitat mostly made up of willow and cottonwood trees. The creek area also supports old-growth ponderosa pines, pretty rare at this elevation.

Pine Creek is a seasonal stream, but waters vegetation that lasts all year.

Back on the main route, continue west toward the prominent red-capped monolith named Mescalito, which separates the canyon upstream. Along the way look for whitetail antelope ground squirrels, cottontails, jackrabbits, and wild burros. On the cliffs you might even see desert bighorns.

About three-quarter miles from the trailhead look on the left, for an unsigned, yet well worn spur trail. This will take you up a small rise where you will find the foundation of an old homestead. Back in 1920, Horace and Glenda Wilson settled in this scenic spot. They built a two-story house with fireplace, and planted an apple orchard and garden.

In 1928 they sold the property to businessman Leigh Hunt. They stayed on as caretakers for eight more years, then moved to Las Vegas. Once abandoned, the house fell victim to vandalism. In 1976 the Nevada Division of State Parks acquired the place.

There is still a lone apple tree in the grassy meadow west of the foundation, but it doesn’t seem to bear fruit. An obvious path heads south through the meadow and over to the creek. If there has been rain recently, the path pools with water and it will be hard to avoid getting your feet wet. Don’t wander off the trail, as there are very fragile plants throughout this area.

Once you have explored the homestead, return to the main trail. If you have kids along, an old hollow tree, on the left side of the trail, is perfect for a child to stand in. Continue on and soon you will come to a signed left turn. This marks the start of the hike’s loop portion, which is only nine-tenths miles.

After you go left to begin this loop, it crosses the Pine Creek drainage and then makes a gradual ascent up its south side. After about one-tenth mile the trail forks and for this hike you will go right. (To the left is the Arnight Trail, a moderate hike which connects to the Oak Creek Canyon Trail at the parking area, a walk of one and seven-tenths miles from this junction.)

As you continue up the trail you will be in one of the most vegetated areas of the hike. Canyon grapes are very prolific here. As you reach the highest elevation of the hike you will be at almost the same level as the tops of the ponderosa trees. There are some drop-offs along this area so watch your footing. In a couple of places the trail is hard to follow so you might need to do some route finding.

The trail soon loses elevation and then loops around to the north where it crosses back over the creek and hooks up to the main trail for your return to the trailhead.

Those who can handle some demanding rock scrambling can travel up the forks on either side of Mescalito. Both are worth exploring but the south fork is easier to negotiate.

The monolith called Mescalito towers over a meadow in Pine Creek Canyon.

Pine Creek Canyon At A Glance

Best season: October–April.

Length: Three miles with optional extension.

Difficulty: Moderate.

Elevation gain/loss: Three hundred feet.

Trailhead elevation: 4,053 feet.

Warning: Washes subject to flash floods.

Jurisdiction: Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area.

Directions: From Red Rock Canyon’s main entrance, take the 13-mile Scenic Drive 10.2 miles to the well-signed parking area and trailhead, on the right.

Low clouds at Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area.

8 First Creek Canyon

The First Creek trail presents a little of everything people like about Red Rock Canyon, including open desert landscapes, riparian areas, a seasonal stream, and spectacular views of the sandstone Wilson Cliffs. Furthermore, it’s an easy trail to access, for it doesn’t lie on the one-way scenic loop.

From the trailhead start your trek west along the obvious well-worn path. For the first mile or so vegetation mainly consists of Joshua trees, banana yuccas, cholla cactus, and blackbrush. You might be lucky enough to see wild burros, coyotes, kit foxes, whitetail antelope ground squirrels, jackrabbits, or cottontails; you’ll surely see evidence of their presence. You’ll doubtless see a few lizards darting about, mostly the zebra-tailed, side-blotched, and desert spiny varieties.

About one mile from where you started, the trail veers right and tops an embankment of the First Creek drainage. There are a few spur trails along here that lead down into the creek bed, but most are pretty steep. Keep going, and you’ll come to the main trail down — a much easier route.

Once in the drainage there are some boulders to sit on and enjoy the surroundings. If there has been rain recently, head upstream a short distance and you will be treated to a waterfall. Keep an eye out for hummingbirds, white-throated swifts, cactus wrens, mourning doves, nighthawks and Gambel’s quail. Pacific chorus frogs and red-spotted toads also make homes here. Canyon grapevines grow profusely up many of the embankments and you will also find a variety of water-loving rushes and sedges. Flanking the streambed are willows, cottonwoods and single-leaf ash trees.

You won’t travel too far within the drainage until you are confronted with dense vegetation, but this lush riparian area is a pleasant place to just relax a while.

Once they have seen the creek bed and waterfall, most hikers return to the trailhead. But those seeking more can continue west into First Creek Canyon. Along the way you will be entering the 24,997-acre Rainbow Mountain Wilderness Area which runs up and over the escarpment. This wilderness area is jointly managed by the BLM and the U.S. Forest Service.

As you continue up the canyon, the trail gets faint and harder to follow and eventually you’ll have to do some rock scrambling. Within the canyon the vegetation changes dramatically due to more water and a cooler environment. Utah serviceberry, desert snowberry, and manzanita thrive here, and there are even Gambel’s oaks and ponderosas scattered throughout.

First Creek Canyon At A Glance

Best season: October–April.

Length: Two to three miles roundtrip with opportunities to extend.

Difficulty: Easy to moderate.

Elevation gain: Three hundred feet.

Trailhead elevation: 3,645 feet.

Warning: Flash flood danger in canyon.

Jurisdiction: Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area.

Directions: From Red Rock Canyon’s main entrance head south on State Route 159 (Charleston Boulevard) about 4.2 miles. Parking area is on the right.

A riparian setting along First Creek.