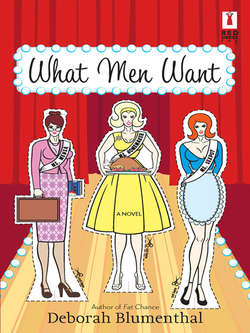

Читать книгу What Men Want - Deborah Blumenthal - Страница 7

Chapter One

ОглавлениеThere are men that you meet and forget. And then there are men who keep you up at night…like Slaid Warren.

It’s not what you’re thinking. Yes, the newspaper photo made him look like a runway model with his deep-set brooding eyes and long dark bangs swept back off his forehead. But that was all beside the point.

Slaid worked for one major New York City newspaper, and I worked for another. So the thrusting and parrying between us was professional, all business, and it took place in print and on the phone, not between the sheets—not those sheets, anyway. We weren’t lovers. We weren’t friends. In fact, we had never even met.

So, you know that I would have done whatever it took to scoop him, not only to get ahead professionally and win kudos from my colleagues, but also to enjoy the end-of-the-day phone call that inevitably followed slighting my success, thus convincing me of my triumph. It was usually brief, just a couple of sentences. But in those few seconds, I chalked up the fact that I had him in a headlock and it wasn’t where he liked to be.

“You missed the story,” he said dismissively in one of our early conversations just months after I had been given the column. Of course he started the conversation without bowing to convention and introducing himself. Unthinkable to him that someone couldn’t recognize his voice, and anyway, we had an ongoing dialogue, interrupted just to allow for new columns to appear.

“If it helps you to deal with it,” I said, leaning back in my chair and warming to his discomfort with the realization that my column had left him in the dust. He laughed heartily as though acknowledging a good joke.

“No, babe,” he said, abruptly cutting off the laughter like a motorboat engine suddenly out of power. “Dealing is not the point. I was out nailing the real story. Your column was filler.” Before I could respond, he hung up.

To backtrack, Slaid Warren and I both covered city politics. “Slaid in the City” was his column. He had me there. How could I hope to top that? Through no effort of his own, he had the good fortune to be born to parents hip enough to give him a cool, albeit weird, name. The only damage I could inflict was to write him e-mails spelling it S-L-A-Y-E-D, in keeping with that of readers who disagreed with him.

My column, I’m loath to admit, had an agonizingly mundane name, echoing a sparrow chirping: “Street Beat.” Nothing there to summon the grit and substance of a tough investigative column. Then there was my vanilla name: Jenny George. As one well-intentioned boyfriend once commented, “It sounds more like the name of a cheerleader or talk-show host than a serious reporter. Why don’t you just change it?”

Just change it? Although there are more things about me that I would change than not, my name isn’t one of them. And while a name that was heftier or more commanding—Lana Davis Harriman or Katherine Clotilde Porter III, for example—might have drawn me into public prominence faster, I love and respect my parents—imperfect as they showed themselves to be when naming their children. (Can you imagine Burt as a name for my older brother? If they had a second son, would he have been Ernie?) Anyway, it was the name they gave me and it seemed almost sacrilegious to consider changing it. Whatever.

As for the column, it had been called “Street Beat” for years, it was well read, and as my editors saw it, why mess with success? To their credit though, they weren’t interested in redesigning the paper and coming up with younger, hipper column heads like, “Thing,” or “What I Was Thinking,” that other papers presumably thought would attract younger readers because they sounded edgier. The paper was secure in its identity and fortunately it had even advanced to the point of covering music written after the “Blue Danube Waltz.”

I had put in ten years at the New York Daily before taking over the column, starting as a secretary—not an assistant, the term used more often these days—right after college. Since I showed outstanding capability in juggling the phones and discreetly giving everyone the proper messages so that their colleagues didn’t find out that headhunters were returning their calls, or worse, places like AA, I was asked to stay on after my six-month probation, sparing me the humiliation of circling ads in the Times and calling people in human resources, a name that made me think of organ banks.

I was promoted to editorial assistant, and finally cub reporter, which meant that I earned the right to go downtown to cover a press conference by the Consumer Product Safety Commission on lawn-mower safety (never mind that as an apartment dweller I had never even seen one) and up to Connecticut to report on a factory that made walking sticks. I had my shorthand to thank—or blame—plus my trusty tape recorder and my reputation for staying with a story until every source was questioned practically to death. I’m not sure if that’s because I’m tenacious about ferreting out the truth, or that I’m so insecure that I overresearch. Let’s just say that I took the old journalism adage to heart—“If your mother says she loves you, check it out.”

The column was actually something of a gift following a tense investigation of a shelter for women who were victims of domestic violence. I spent two nights in one and wrote a story exposing the failures of the system, including a lack of policing that led to boyfriends finding their way in and spending the night. Apparently the current columnist had opened the paper one morning to find an obit of a colleague who died at age fifty of a massive heart attack and immediately submitted his resignation so that he could spend more time with his family. But ultimately the decisive factor that led to my becoming a columnist with all the power that comes with it might well have been the fact that the stars were in proper alignment.

In any case, it was a prized, if competitive, job. It was a bit daunting, at first, to find myself up against some ace metro reporters, including Slaid, who had a far wider net of contacts than I did and far more experience. Being male didn’t hurt him either, plus he was slick at taking advantage of the buddy network built up through jobs at various papers and magazines, so that disgruntled insiders seemed to gravitate to him. Then once he sat down with them, he was one of the guys and always on their side, at least until he was in front of the computer screen and the story came out.

And how was I viewed? Think perky former cheerleader. In fact, I was told on my thirtieth birthday that I had the cherubic face and fawning grin of an eighteen-year-old Goldie Hawn. Not a bad thing, but needless to say, with only one year now on the job, I had a lot of catching up to do to earn credibility and authenticity.

But back to Slaid. Be assured that I would never denigrate a colleague needlessly. He was known to be trustworthy to a fault, at least judging from the fact that months back he had spent a few weeks locked up in prison for refusing to turn over his notes after he interviewed a mafia don following the murder of a member of a rival family. It led to a juicy column and his refusal to cooperate with a police investigation on the grounds that New York’s shield laws protected journalists from turning over their notes and revealing their sources.

I don’t believe for a minute that Slaid withheld his notes—as some of my more mean-spirited colleagues have flippantly suggested—because he knew he could count on his buddies from the six o’clock news to make a show of hanging out supportively at the prison 24/7, guaranteeing that his popularity would soar, not to mention bringing him hearty fare like pasta alfredo and osso bucco from Little Italy so that he would be spared the ordeal of subsisting on prison food. That wasn’t such a really big deal. After all, he didn’t get to drink the Pinot Grigio or the Barolo. They were confiscated; I know that for a fact.

But watching him on TV, I realized that he oneupped me in another, more fundamental way. As he was interviewed coming out of prison (and the hype! You’d think he’d served twenty years and a wrongful conviction was overturned), he stops and turns to stare directly into the camera’s eye, speaking softly, in a controlled, almost wounded kind of way—like an Italian film star in a noirish setting. No one could miss the fact that his deep-set eyes and shadow of a beard, combined with the upturned collar on his worn sport jacket, gave him that soulful bedroom look that I know he was going for. And what did he say? Would you believe he quoted James Madison? “‘Popular government without popular information or the means of acquiring it is but a prologue to a farce or a tragedy.’”

Bravura performance. The erudition coupled with the intensity of his look. Little me, on the other hand, would try and fail at impersonating the lost, waifish air of a Daryl Hannah type. Instead, I’d look vulnerable and helpless. Instead of alerting viewers to the fact that my incarceration was part of a distressing new pattern of attack on the freedom of the press, I would merely look distraught as though I was weathering the flu. I’d undoubtedly say something rambling and incoherent because I hadn’t slept well due to the hard beds and thin mattresses, the claustrophobic sizes of the cells and the overcrowded conditions. My hair would be twirled up in a ponytail so that it didn’t droop like seaweed because of the absence of Aveda Sap Moss shampoo or Kiehl’s Silk Groom (do they let you take those things to jail?)—my lifelines to vibrant hair. And without Nars Orgasm blush and Chanel lip gloss, I’d look merely washed out, not sultry columnist wronged by the system.

So instead of reporting it, Slaid Warren was the news for a good week after that, and as I learned, spending time in the big house, especially for holding such high moral values, can really up your Internet-chatter quotient, not to mention boosting future book advances. If I didn’t know better, I would have guessed that Slaid had arranged it, maybe even sleeping with the judge (who was divorced and not half-bad-looking, even in her muumuu-size black robe) to set the whole thing up.

But these days, praise the Lord, Slaid was out, a free man—free to take himself to movie premiers and hang out at all-night celebrity-backed restaurant openings that were destined to be covered in the next day’s papers where he was photographed snuggling one fetching model or another and generally cavorting with the A-list.

And while we had very different types of social lives and went our separate ways, we both seemed to have similar instincts when it came to sniffing out a good story, leading to columns that were often breaking the same news.

The problem was we were more than just rivals in our columns; we had become rivals in our lives, elevating one-upmanship to a spectator sport for readers, not to mention the sword sharpening that went on privately between us, on the phone.

What do I mean?

When I wrote about the mayor using workers under city contract to renovate playgrounds to work in his Fifth Avenue town house, Slaid had a similar column as I guessed he would. So I was lucky enough to know someone who worked for the construction company. I topped him by offering obscure details about the particular style of moldings that the mayor was installing (egg and dart) and added another juicy detail—he had them working overtime so they could finish the job in time for his annual Christmas bash. (Catered by a company headed by a friend of a friend. I held off describing the canapés that he ordered, baja ceviche, crab rangoon and caviar d’aubergine, among others, and the cranberry Stoli martinis, juicy details to foodies, but really a bit beside the point.) That phone call was a memorable one too.

“Egg and dart?”

I didn’t say anything.

“What the hell is egg and dart?”

“Ask one of your interior-design sources,” I said.

“Why would I know people like that?”

“Aren’t you gay?” I asked, expertly choking back the laughter welling up in my throat.

“Fuck,” he said, hanging up.

Then there was the column I wrote about a writer at Slaid’s paper who was caught fabricating a news source in a story that he covered without ever going to the scene. Story after story ensued as if the paper was so guilt-ridden that it felt it had to purge itself repeatedly, in print.

I ended my column:

News about newsmakers is replacing the real news, inadvertently turning liars and cheats into media stars and future authors of tell-all books. Can’t TV-news types find more reputable people to interview? Can’t Slaid Warren drop his long columns about soul-searching over lunch at Vong and instead find someone gifted, talented or at least more illuminating to lunch with for his column? It’s time to leave the fate of bad journalists to the editors and publishers who hired them and move on to the real news.

“So why didn’t you write about your lunch with heads of state instead of wasting trees to write about my column?” he said, putting me on the spot.

“You’re too sensitive,” I said, yawning. “Didn’t your mother ever tell you not to take things so to heart?”

“It happens to be a major scandal among serious journalists. I guess that fact passed you by.”

“I got it,” I said, “about eight million words ago. Give it up.”

“Sweetheart,” he said, getting to his famous exit line. “I didn’t get where I am by giving up.” He hung up and there I was holding the phone once again after the line went dead. I pressed redial and he picked up on the first ring.

“Slaid?”

“Yeah.”

“Just one more thing,” I said. Then I hung up.