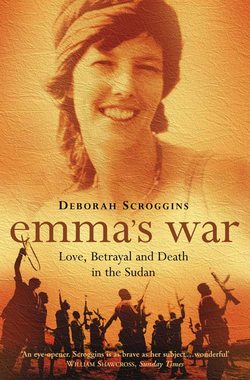

Читать книгу Emma’s War: Love, Betrayal and Death in the Sudan - Deborah Scroggins - Страница 8

Chapter One

ОглавлениеAID MAKES ITSELF out to be a practical enterprise, but in Africa at least it’s romantics who do most of the work - incongruously, because Africa outside of books and films is hard and unromantic. In Africa the metaphor is always the belly. ‘He is eating from that,’ Africans will say, and what they mean is that is how he gets his living. African politics, says the French scholar Jean-François Bayart, is ‘the politics of the belly’, The power of the proverbial African big man depends on his ability to feed his followers; his girth advertises the wealth he has to share. In Africa the first obligation of kinship is to share food; and yet, as the Nuer say, ‘eating is warring’. They tell this story: Once upon a time Stomach lived by itself in the bush, eating small insects roasted in brush fire, for Man was created apart from Stomach. Then one day Man was walking in the bush and came across Stomach. Man put Stomach in its present place that it might feed there. When it lived by itself, Stomach was satisfied with small morsels of food, but now that Stomach is part of man, it craves more no matter how much it eats. That is why Stomach is the enemy of Man.

In Europe and North America, we have to look in the mirror to see Stomach. ‘Get in touch with your hunger,’ American diet counsellors urge their clients. Hunger is an option. Like so much else in the West, it has become a question of vanity. That is why some in the West ask: Is it Stomach or Mirror that is the enemy of Man? And Africa - Africa is a mirror in which the West sees its big belly. The story of Western aid to Sudan is the story of the intersection of the politics of the belly and the politics of the mirror.

It’s a story that began in the nineteenth century much as it seems to be ending in the twenty-first, with a handful of humanitarians driven by urges often half hidden even from themselves. The post-Enlightenment triumph of reason and science gave impetus to the Western conviction that it is our duty to show the planet’s less fortunate how to live. But even in the heyday of colonialism, when Western idealists had a lot more firepower at their disposal, Africa’s most memorable empire-builders tended to be those romantics and eccentrics whose openness to the irrational - to the emotions, to mysticism, to ecstasy - made them misfits in their own societies. And the colonials were riding the crest of a wave of Victorian enthusiasm to remake Africa in our own image. If the rhetoric of today’s aid workers is equally grand, they in fact are engaged in a far less ambitious enterprise. With little money and no force backing them up, they are a kind of imperial rearguard, foot soldiers covering the retreat of a West worn down by the continent’s stubborn and opaque vitality. They may be animated by many of the old impulses, idealistic and otherwise, but they have less confidence in their ability to see them through. It takes more than an ideal, even an unselfish belief in an ideal, to keep today’s aid workers in place. Emma had some ideals, but it was romance that lured her to Africa.