Читать книгу Carry The Light - Delia Parr - Страница 9

Chapter Four

ОглавлениеA fter seven seemingly endless days, Charlene felt as if she had spent an entire week in a playground, stuck on one end of a seesaw. The neighborhood bully sat on the other end and constantly taunted her by pushing her up into the air and holding her there before jumping off again and again, slamming her hard and fast to the ground.

In reality, she had spent every waking hour for the past week at Tilton General Hospital, a bizarre playground filled with mysterious flashing and beeping equipment, where Aunt Dorothy was recovering from her little spell—a mild heart attack.

Days, when Charlene was encouraged by the promise of her aunt’s progress, were invariably eclipsed by days when the bully, aka CHF and diabetes, yanked her down from hope to fear and doubt. Other than taking time to retrieve her aunt’s living will from the bank, she had taken only one other break, the morning that two women from the Shawl Ministry had stopped by to visit her aunt and deliver a lap shawl they had made for her. Charlene was also able to grab an hour alone when Annie Parker and Madeline O’Rourke, her aunt’s closest friends, came by each afternoon, which deepened Charlene’s desire for a supportive friend of her own.

Charlene was pleased, however, that once she had called her children, both Greg and Bonnie had come to the hospital to see Aunt Dorothy, although they each had had to get right back to their homes and had been unable to stay overnight to visit longer with Charlene.

Yesterday, her aunt had stabilized enough that the doctors discussed discharging her. Now, on Friday morning, Charlene and Daniel were in Aunt Dorothy’s room for a meeting with the hospital social worker, Denise Abrams. Fortunately, her aunt’s roommate had left earlier for a test of some sort, so the group that gathered about Dorothy Gibbs’s bed had plenty of privacy.

Charlene glanced at the faces and smiled to herself. No one was under fifty. Over the past week, she had seen a multitude of doctors, nurses, technicians and aides. Most of them were young enough to be her children, and she shuddered to think that at fifty-nine, she could be a grandmother to some of them. Although they all appeared to be competent and qualified, Charlene felt more comfortable with hospital workers who had been alive long enough to know that the best way to eat a Mary Jane was to suck on it and to remember a time when a chocolate bar, with or without almonds, cost only a nickel.

Aunt Dorothy sat in her bed, obviously enjoying being the center of attention. For the first time since she had entered the hospital, her hazel eyes held a bit of sparkle again, but she still looked forlorn and bedraggled.

Her pale blue hospital gown hung loosely around her narrow shoulders. Mottled bruises surrounded the small white bandages on the back of both her hands and at the crease in her elbows. Her complexion was pasty. Her dark gray curls were flattened in some spots on her head, while unruly clumps stood up in other places, making her look as if she was wearing a broken tiara.

She was a queen held captive on her throne. An IV line snaked from the back of her hand to several bags hanging on a stainless-steel pole, and wires linked her to monitors that measured her heart rate and blood pressure. A urine bag and catheter tubing were discreetly concealed beneath sheets near the floor, and bars on both sides of the mattress gave her something to hold on to, helping her to shift more easily in bed.

Charlene stood next to the pillow, resting a hand on her aunt’s shoulder. Daniel held on to the top rail with one hand on the other side of the bed. Charlene studied him as he told her aunt about the young boys’ basketball team that was coming to camp in the state park this weekend.

The crisp white sheets on Aunt Dorothy’s bed offered a stark contrast to Daniel’s perpetual tan, acquired from a lifetime working as a park ranger. He was a stocky, well-muscled man with dark, wavy hair. He had passed on his cleft chin and love of the outdoors to their son, Greg, while their daughter, Bonnie, had inherited his fabulous blue eyes and the tendency to be reserved and not to reveal thoughts and emotions.

Standing with him, as she had done for more than forty years, Charlene realized again how physically unlike one another they were. She had often said that her figure resembled a salt-water taffy: plump from top to bottom. She had pale skin and hair she’d kept light, long after time had darkened it and later turned it white.

Her life, since she’d married Daniel, had been built around her home, her children and her church. Unfortunately, by the time the nest she and her husband shared was empty, they had become strangers who had two children in common, but little else—except that they both loved Aunt Dorothy.

Grateful for his support during the past week, Charlene glanced at the end of the bed, where Denise Adams stood next to the papers she’d brought to the meeting and stacked in neat piles on the table Aunt Dorothy used to take her meals. For a woman who spent a good part of her professional life helping patients and their families make the transition from hospital to home, the social worker had an unusually stern and rigid turn to her mouth, and the expression in her light brown eyes was pure business.

Charlene was not impressed—until Daniel and Aunt Dorothy finished their conversation and Denise started the meeting. “As you know, Dorothy, Dr. Marks feels you’re just about ready to leave the hospital,” she said in a sweet, soothing voice that immediately set Charlene at ease.

For the life of her, however, she would never get used to hearing the hospital staff refer to her eighty-one-year-old aunt by her given name. Unless requested by the patient, titles and last names, Charlene had learned, were taboo under new guidelines that were supposed to guarantee patient privacy. But no one had asked Aunt Dorothy what she preferred.

“I wouldn’t mind staying a few days longer,” Aunt Dorothy murmured, clearly reluctant to return home and resume the independent life she had always led.

“We’ve got a number of options for you and your family to consider, which is why I thought it best that we all be here together,” Denise replied. “I thought I might briefly explain what those options include. First and most importantly, we all realize you’re not quite up to living alone again.”

When Aunt Dorothy nodded, Charlene lightly pressed her fingertips against her aunt’s shoulder to offer support. She was relieved that the social worker had not come right out and said Aunt Dorothy would never live alone again.

Denise smiled. “We have several alternatives you can consider.”

Aunt Dorothy stiffened and blinked back tears. “Not a nursing home. Please. I—I never, ever want to give up my home and spend my last days in a nursing home,” she whispered.

“You really don’t need to move permanently into a long-term-care facility,” the social worker assured her, clearly avoiding the words “nursing home.” “You could benefit from a short-term stay in any one of the rehab facilities in the area, if you have the resources. While you’re there, you could consider selling your home and moving into an assisted-living facility. I could help you and your family in that regard, as well.”

Charlene, seeing the devastation and panic in her aunt’s eyes, didn’t hesitate—not even to consult Daniel. “Aunt Dorothy, you can come live with us until you’re strong enough to go home again,” she offered.

Relief flooded her aunt’s features. “I wouldn’t be in the way. Not for an instant. And I’d be good and quiet, too,” she promised, looking from Charlene to Daniel and back again.

Charlene smiled and glanced at her husband, albeit belatedly, for his approval.

He looked at her aunt, instead, and smiled. “You can live with us for as long as you like.”

The social worker frowned. “As I recall, the two of you don’t actually live in Welleswood,” she said to Charlene.

“I have my business here, but we live in Grand Mills,” Charlene replied, wondering why that should make any difference.

“Near the edge of the Jersey Pinelands,” Daniel added.

The woman’s frown deepened. “That’s a good hour away. Being that far from Dorothy’s physicians could present problems. When she experiences another episode, which seems likely given the progressive nature of her illness, there might not be time for you to bring her back here.”

“You could change doctors for the time being. People do that all the time,” Daniel suggested. “I’m sure the hospital could transfer your records to a closer facility.”

Aunt Dorothy blinked back a fresh wave of tears. “But then we’d have to change back again when I move home. That’s an awful lot of trouble for everybody.” She sighed and worried the tissue in her hands. “It seems to me the good Lord should just call me Home, but He doesn’t appear to want me yet.”

Before Charlene could comment, the social worker responded, “Perhaps a better alternative would be to hire someone to live with you at your own home, assuming you have both the room and the resources. Whether you choose a home health aide or a companion, you’d receive the help you need and be able to keep the same doctors.”

Aunt Dorothy’s face lit with interest before she dropped her gaze.

Charlene swallowed hard. Hiring anyone to live with Aunt Dorothy full-time was well beyond the elderly woman’s means, but even if it wasn’t, Charlene could not imagine letting a stranger care for her beloved aunt. “We’re family. We take care of one another,” she murmured, patting her aunt’s shoulder. “I have to come to work in Welleswood five days a week anyway, so why don’t I just move in with you, temporarily, until you’re up to living alone again,” she suggested, unable to bring herself to suggest that Aunt Dorothy would never actually be well enough to live by herself again.

Based on the literature she had read, and what the doctors had told her, the progressive nature of CHF—combined with the complications of aging and diabetes—meant that Dorothy Gibbs would probably never be self-reliant again. But pointing that out now, when her aunt was so vulnerable, just didn’t feel right to Charlene.

She looked over at Daniel again. “You could come and stay with us for weekends, couldn’t you?”

He winked at Aunt Dorothy. “Why not? You’re still my best girl, aren’t you?”

“I can’t ask you two to uproot yourselves like that,” Aunt Dorothy argued, but her voice was soft and unconvincing.

“You didn’t ask. We offered,” Charlene countered, grateful for her husband’s support.

“I’ve been promising you all winter that I’d come take a look at that backyard of yours once spring came and clear it out for you,” Daniel added. “It would probably be a whole lot easier for me if I had a few weekends where I could work in the yard without driving back and forth.”

Aunt Dorothy batted her lashes at him and smiled demurely. “I haven’t had anyone over for Easter brunch for years. Not with the yard so overgrown. It’s lovely to think we could have brunch by the creek again this year. Do you think Greg and Bonnie could come, too?”

“The kids aren’t coming home for Easter this year, remember?” Charlene prompted, to remind her aunt that they had talked about this when Greg and Bonnie had visited her.

“Greg and Margot are spending the holiday with her parents and Bonnie is going to Spain as a chaperone with the Spanish club at her school,” Daniel added. “Charlene and I will be there, though. I can’t promise to have the yard cleared out by then, but I’ll try.”

“You’re such a strong man. I just know you’ll have my yard looking better than it ever did by Easter,” Aunt Dorothy said confidently.

Watching her husband and aunt chatting, Charlene blinked hard. Aunt Dorothy was actually flirting with Daniel, and he was absolutely beaming!

“I think you’ve found a wonderful solution.” The social worker smiled proudly, as if the idea had been hers. “I’ll speak to Dr. Marks this afternoon. From what he told me earlier today, our patient might even be able to go home tomorrow,” she offered. Then she packed up her papers and left.

“My house keys are in my purse. You took that home with you, didn’t you?” Aunt Dorothy asked as she took a fresh tissue from the box beside her bed.

“As a matter of fact, I still have it in the trunk of my car. I wasn’t sure if you’d need anything in your purse or not.”

Her aunt smiled. “Good girl. Instead of staying here all day, why don’t you go to my house and air it out a bit? You could move a few things around to make up the spare bedroom for you and Daniel to use while you’re staying with me. Just stick anything in your way up in the attic or anywhere else you find room. I’m afraid there isn’t much in the refrigerator, either, except for a few old leftovers that probably need to be tossed out.”

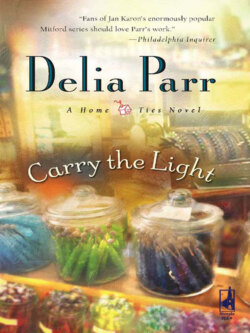

She paused to mop her brow with the tissue. “Unless you need to get to Sweet Stuff. You haven’t been at your store all week.”

“The store is fine. Ginger King offered to work full-time for me this week so I could be here with you. I’ll get your house ready, instead,” Charlene reassured her.

“What about you, Daniel?” her aunt asked.

“I’m afraid I have to get back to work. I’m on duty this weekend, but I can start on that yard of yours next weekend,” he promised.

“Well, go on, then,” Aunt Dorothy said, waving them both away. “You two have important things to do.”

After a round of hugs and kisses, Charlene walked to the elevator with her husband. “Thank you,” she murmured as they waited side by side for the elevator.

He nodded, but kept his gaze on the arrows over the elevator. “Sure. Nothing else made much sense.”

The down arrow lit up, a bell sounded and the elevator doors opened. “It won’t be for long,” Charlene offered as they stepped into the empty elevator, saddened to think Aunt Dorothy’s days on this earth were nearing an end.

He shrugged and pressed the button for the lobby.

“Maybe it might do us both some good to spend a little time apart during the week,” she said, giving voice for the first time to the fear that the indifference that had marked their marriage these past few years might be too great to overcome.

He let out a long, deep sigh. “If that’s what you want,” he said hoarsely.

And her heart trembled.

Maybe that’s what he wanted, too.