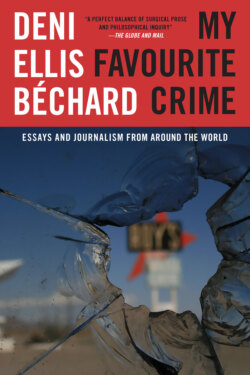

Читать книгу My Favourite Crime - Deni Ellis Bechard - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Disobedient Ancestors (2009)

ОглавлениеMy father was born in 1938 in Rivière-au-Tonnerre, Québec, a town on the north coast of the St. Lawrence and an eleven-hour drive northeast from Montréal on modern highways. There the river joins the gulf and is over 112 kilometres wide. In the early twentieth century, ferries plied the seaway during the few clement months before ice choked it and small airplanes were needed to carry men across to timber camps. Blizzards closed the coastal roads and the mail made it through in a truck with caterpillar treads, creeping along rises like a prehistoric insect.

Rivière-au-Tonnerre had plenteous cod stocks, boasted telephone lines and occasional electricity, and was managed by Robin Jones and Whitman, a family company whose founder was originally from the Channel Island of Jersey. My grandmother, Yvonne Duguay, was born in 1908, one of five sisters whose mother died when they were children. At twenty, Yvonne married Étien Boudreau, a young accountant for Les Robins, as the company was known, and the couple had two daughters and a son before Étien died suddenly of an ulcerated stomach. After several years as a widow, Yvonne married my grandfather, Alphonse Béchard, a dark-skinned fisherman from Gaspésie who had a reputation for fighting and for having once gotten drunk and blown up a large black bear with a stick of dynamite. Soon after, my aunt was born and then my father, Edwin. A year later, Alphonse decided to return to his family land and paternal fishing waters and moved them all to the south shore, to a village called Les Méchins, on the southwestern cusp of the Gaspé Peninsula, where it meets the region known as Le Bas-Saint-Laurent.

My grandmother, who lived to be 104 years old, often lamented that move to the impoverished landscape of Gaspésie, to a house without electricity or telephone or running water, on a ledge of flat land above a narrow road that threaded the ragged coast. Below was a steep descent to the shore and a series of rocky islands, where Alphonse built a salmon weir. From the house, another steep path led up to a range of mountains on which he maintained his potato fields and where my father worked from spring to fall each year until he was sixteen.

The name of the village, Les Méchins, was a bastardized version of les méchants, “the mean ones,” which some say was taken from a folktale about a bellicose giant who once lived there and terrified the Indigenous people before missionary priests drove it off; another version claims that it was the Indigenous inhabitants who needed subjugating. There, the St. Lawrence spans almost forty-eight kilometres, and for those working in the high fields on clear days, the stony face of the north coast appears from beyond water, distantly, like the moon.

• • •

My father hated Québec. He’d broken contact with his family before I was born in 1974, and I never set foot in Québec or met my father’s family until after his death, when I was twenty. Thanks to his stories, the province had occupied too great a place in my imagination, and it took me years to see it not as a land of hardship and oppression, but as the modern, secular, highly educated, and prosperous society it is today.

When I was a child, the stories he liked to tell best were those of hard work in mines or on dams, or of his travels in the Yukon and Alaska, or through Nevada and California to Tijuana. He described fights, sometimes over women, or random confrontations that sounded more like sport. Working, he’d seen a logger sheared by a frozen tree that split and spun suddenly into what he called a barber chair. At a uranium mine, each miner was obliged to drink two glasses of milk to coat the lungs before he went underground. That first week my father laughed at the free drinks and gulped them down, but he saw no pleasure on the tin-coloured faces of the older men. A couple of months later, when the occasional cough filled his mouth with coarse, sooty phlegm, the odour of milk was enough to make him gag. The desire for a better life stayed in his gut like an inexplicable hunger.

My father rarely spoke of his family in these stories, only occasionally making a brief reference to an uncle or cousin, and just as quickly he would look down, his dark eyes distant, and change the subject. From all that he told, he seemed to have lived in the company of men, and the stories he liked best were of clever men, those capable of outsmarting police or bosses on construction projects, the tough in his village who, after a few whiskeys at the local pub, would jump up and kick the ceiling with both feet for everyone’s entertainment. He told and retold his own feats: his escape from a lumber camp before the arrival of a flood, or how he won a brutal fistfight with a big German by biting his nose and holding on with his teeth until the man began to cry.

Much later in his life, when he was less certain of his wit and lived alone in failing health, he told other stories without joy. He mentioned his family now, the less charming violence of his father, the poverty of his village, or the first time he saw electric light and indoor plumbing. He was no longer the trickster, the clever, self-sufficient adventurer who’d crossed the continent repeatedly, but an aging man recalling a boyhood in a Catholic village, haunted by a history so complex that it would take years before I could understand how it had shaped his life. He spoke of the absence of his family as if it were a mystery to him. He spoke of it with great effort, and within that mystery, behind it, in everything he said about Québec, was the Church.

• • •

Gaspésie comes from the Mi’gmaq word gespe’g, which means “the end (of the earth).” French explorer Jacques Cartier found safe harbour in Gaspé Bay in 1534 and erected a cross to claim the territory for King Francis I, but not until 1608 did Samuel de Champlain establish the first permanent settlement at the site of present-day Québec City.

As it was for the Puritans in New England, the New World seemed to the Roman Catholic Church a call from God to create a model society. But this frontier religion would have much to withstand. As a colonial and missionary faith, it strove to mitigate the perceived wildness of the Indigenous inhabitants as well as the brutality and licentiousness of the unruly profiteering colonists. If the Indigenous tribes were to be converted, the Church believed it needed to present impressively pious colonists as role models. It soon became state and government, managing daily life in villages and trading posts as well as moderating colonial relationships with Indigenous Peoples and with Europe. While thousands of seasonal French workers arrived seeking furs and cod, priests came in droves, just as serious about souls.

Yet New France failed to build as substantial a population base as New England partly because of its climate and partly because its seasonal workers lacked motivation to immigrate permanently. The educated and wealthy came only in the summer, and permanent colonists endured not only harsh winters but the military encroachment of the British and the occasional piracy from the not-yet-independent Americans. In 1758, when British General James Wolfe raided and took control of coastal settlements in Gaspésie, many of the French returned to Europe, leaving the poorest and least-educated with only the Church for guidance. In 1759, Québec City fell, and with the last naval confrontation, the Battle of Restigouche in 1760, the British had opened the way to the conquest of most of North America.

For the Church in Québec (the region that the British designated as Lower Canada from 1791 to 1841), the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries were the most difficult. From 1763 until 1774, the British attempted to assimilate the remaining French, excluding Catholics from public office and banning the recruitment of priests. British authorities wanted to promote the Church of England and stomp out popery, and only with the beginning of the American Revolution did the British see the benefit of the Church. The threat of French Canadians siding with the American revolutionaries was great, and in part because the Roman Catholic Church opposed democratic ideas, the British Parliament passed the Québec Act of 1774, which gave recognition to French law and language as well as to Catholicism. This move served both to pacify the French and to cement the role of the Catholic Church in British rule.

For those like my grandparents and great-grandparents, who lived 4,800 kilometres of blustery North Atlantic winds away from Paris, in as remote a place as Gaspésie, it was difficult to imagine that the French Revolution had so greatly shaped their lives. But while revolutionaries in Paris were reconfiguring the deck of cards, replacing the kings with images of Rousseau and Voltaire and destroying religious monuments, the priests they had exiled were arriving in Québec, determined to create what they saw as the last bastion of true Christianity. Just as it had struggled against British rule, the Church now sought to prevent the spread of nationalist and democratic ideas from France and the United States. It already had a policy of encouraging population growth, with the aim of absorbing or outnumbering other ethnic groups who had smaller families. The priests determined that the best barrier against the infiltration of French and American ideas would be large agrarian families who did not enter the merchant class and remained relatively uneducated. Until the 1840s, the Church struggled to provide priests for a population that doubled every twenty-five years and to confront a growing educated elite that aspired to leadership within Québec and espoused nationalist and liberal values, including freedom of speech. In order to stay in power, the British sided with the Church on all of these issues, and when British troops crushed the nationalist rebellions of 1837 and 1838, the Church was positioned to solidify its power.

For the next 120 years, it worked to Christianize every aspect of life in Québec. It built convents and colleges, ran schools and hospitals and charity organizations, trained thousands of new priests and created a Catholic political elite. Québec became a virtual theocracy. The Index Librorum Prohibitorum – the Church’s list of banned books – was enforced, movies censored or bowdlerized, and conservative newspapers published for the masses.

In Gaspésie, the priests struggled to preserve order during the long frustrating winters when the cod fisheries shut down and there was no work. They hung black flags before the houses of men who drank, to shame them and protect families from the threat of violence and incest. However, if a married woman went two years without having a child, the curés refused to let her say confession, insisting that childbirth was a woman’s duty and that failing to maintain this duty constituted a sin. My grandmother did her part with ten children from two marriages; some women even had families twice that size. As a result, some have claimed that the population of Québec grew more rapidly than any other in recorded history.

Whereas in Europe the Church often vied with the state for power, it became the authority in Québec, guaranteeing the docility of its people to the British in exchange for near autonomy. In resisting so much, it had grown stronger than its European counterpart. It had endured hardship, lawlessness, and revolutionary ideas as well as English colonialism, a new wave of immigration, and the encroachment of Protestantism. It created a homogenous French-speaking people from what it saw as a mongrel crowd of Acadian and Norman, French and Métis, Irish and English and Scot, and, in doing so, it preserved a spoken French more likely to resemble the language of Balzac than anything to be heard in or near Paris. Just as vessels carried men across the Atlantic, Catholicism became the vessel that would carry the French language into North America’s twentieth century.

• • •

My paternal lineage traces itself not back to France but to the island of Guernsey, another piece of land that, like Québec, the English and the French contested. The Channel Islands, however, were passed back and forth far more frequently and over many centuries before ending up under English sovereignty and serving as a buffer against attacks from the French, who briefly occupied them during both the Hundred Years’ War and the War of the Roses. Much later, James, Duke of York, sought refuge in Jersey during the English Civil War and later, upon his ascension to the throne, granted Sir George Carteret, the island’s governor, land in the American colonies that was to be named the Province of New Jersey.

The Channel Islanders had long taken interest in the New World. Skillful sailors and merchants, they had spent centuries as middlemen between the French and English, and had exploited the cod fisheries in Newfoundland since the seventeenth century. With the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1763, they found themselves in a privileged position. Many of them spoke both French and English and, as British subjects, could manage the French populations in the St. Lawrence, once again in the familiar role of middlemen. The companies of Charles Robin and the Le Boutillier brothers managed cod shipping for so long that my grandmother often spoke of her Jersey village and les Jerseys who ran it.

William Thomas Bichard (later changed to Béchard), my first ancestor to arrive from Guernsey, did so as a fourteen-year-old orphan. He debarked on May 6, 1835, and later married Ellen Henley, the daughter of a family whose ancestors had presumably fled to Gaspésie during the Irish Famine of 1740–1741. Their eldest son, Thomas, had another Thomas, who was the father of my grandfather Alphonse. Over that half-century, the Béchard family spread down the Gaspé Peninsula, many of them along the Baie des Chaleurs and into northern New Brunswick, where they mingled with Acadian refugees from the British deportations. Over the years, the Béchards gained an infusion of Indigenous blood, my grandmother and uncles occasionally mentioning their New Brunswick cousins who “walked like Indians.” Once, my grandmother, in insisting that my grandfather’s darkness did not indicate métissage, mused that she had always wondered at his lack of body hair, a trait that, according to her, was more common among Indigenous people.

Like the first French settlers of the history books, my grandfathers and uncles – sailors and fishermen and merchant marines – are portrayed in family stories as hardy travellers. In them, I have found echoes of les coureurs des bois, the Canadiens fur trappers. Québec’s eighteenth- and nineteenth-century authorities wanted its people to stay in agricultural zones and leave the lucrative trapping to the Indigenous Peoples, but les coureurs des bois refused and journeyed deep into the continent, intermarrying with the original inhabitants, learning from them the arts of voyage and survival.

In the nineteenth century, the term Canadien was used for any French-speaking North American, whether from New Orleans, Québec, or the Great Lakes. Les Canadiens were known for itinerancy, many born of Métis and Indigenous mothers, their identities as close to the bloodlines and demarcations of the original inhabitants as to the Europeans whose studied mapping had yet to reveal the continent’s interior. The American government often employed them for their skills. They served as watermen to take Lewis and Clark west. In the 1804 expedition, les Canadiens were enlisted as temporary, as engagés, in the U.S. Army Corps of Discovery. My favourite character, Pierre Cruzatte, was the principal waterman who piloted the canoes and keelboats during the long journey. He was a lover of dog meat and a fine fiddler who entertained both his own men and their Indigenous hosts with his skill. Blind in one eye and nearsighted in the other, on one hunting expedition he accidentally shot Captain Lewis in the left thigh, mistaking him for an elk.

Two hundred years later, it is easy to forget how so much history is distilled into a ramshackle village on a desolate coast in Gaspésie, a place now reasonably sedentary, though centuries earlier it was the site of endless crossings and miscegenation. In many ways the Church was both the flame and alembic in the process of homogenization. Until the end of her life, my grandmother’s piety was unflinching, her prayers and devotion constant, echoing centuries of doctrine learned from priests who themselves were taught that men do not have rights, but rather duties, and that change leads only to secular chaos and immorality. She insisted that the modern world has failed us and that someday, so that people can return to wholesome lives, we will embrace the Church again and the old ways of living.

But those old ways also bred men with grammar-school educations and a love for profanity and stories and revelry – and above all, a hatred for authority. Of everyone I have known, my father was the person who most powerfully expressed his hatred of religion, unable to speak of the village curé without rage, without at least once referring to him as “the fucking priest.”

“Those priests,” he would say, gritting his teeth when speaking of the Québec that he hadn’t visited in over a decade, “those fucking priests.”

• • •

When my father was fifteen, the only winter industry was logging on the north coast, so he lied about his age, a sixteen-year majority being required in order to join the men who would be leaving. The village priest, Curé Félix-Jean, heard what he had done and informed the company recruiters, thereby forcing my father to spend another long winter with the women and children.

“He wanted to be with the men,” my aunt told me. “He hated being trapped in the house and having to do children’s chores.”

In Les Méchins, snow arrives as early as October, and trees do not bloom until June. My father managed the farm, taking care of pigs and horses and chickens, and the next winter he finally crossed the St. Lawrence in an airplane and worked in a logging camp. The summer afterward, he was hired on a dam on Northern Québec’s section of the Canadian Shield, an immense watershed whose many hydroelectric projects now power the cities of Canada and New England. He sent 70 to 80 percent of his paycheques home so that his five younger siblings and the children of his sisters could have better educations.

By the time he was nineteen, he’d worked in a uranium mine and on a high-rise construction site alongside teams of Haudenosaunee ironworkers. Then, after his best friend fell to his death, he quit and broke contact with his family, changing his life as if the reels of two very different films had been spliced together. His youthful journey of exploration and freedom from winter and home and church was transformed into the life of a criminal. He spent the next fifteen years safecracking and carrying out armed robberies, working his way west across Canada and then south through Montana to Las Vegas and finally to Los Angeles. He robbed jewellery stores and banks, and laundered hot items and cash with the mafia, or so he claimed when he bemoaned their bad rates. Not surprisingly, there were occupational hazards to such a life, and he spent half of that time in Canadian prisons and American penitentiaries before he was deported to British Columbia. He lived there until his death at the age of fifty-six.

As sensational as his life seemed when he told it, a simple question remains, one that has long haunted me: How does a young man from a fishing village in rural Québec align himself with such ambitions? Other questions tumble from this one: What was the source of his audacity, his longing (even desperation) to escape and to erase all traces of the past, driving him to find a new place in an unfamiliar landscape? Where did that revolution occur? Even now, so many years after his death, I recall his hatred of his home, his hatred of Québec, and above all his hatred of the Catholic Church.

• • •

Curé Félix-Jean animated many of my father’s stories and many that my uncles and aunts still tell. His vigilance kept them from smoking and drinking and trysts. He especially disliked the young men of the village. Whenever he spoke with one he particularly disdained, he cleared his throat noisily, took out his handkerchief, and hung it by two corners like a veil before the face of the boy while still speaking to him. Then he spat into it, the dirty fabric jerking with its load of phlegm.

Some of my father’s stories, though, were more typical, such as his rage at being punished for having no sins to tell at his first confession.

“We worked,” he told me. “We did nothing but work, and that fucking priest made us invent sins. We didn’t have toys. All we did were chores. We got up and fed the animals and picked up wood or worked in the fields. When was there time to sin?”

As with the English “breakfast,” the French déjeuner means “to break fast,” dé- meaning “un-” or “undo,” and jeûner “to fast.” The French have eliminated this by having un petit déjeuner, their déjeuner now meaning lunch – a nonsensical notion – whereas the Québécois call their three meals déjeuner, dîner, and souper. The first Friday of each month, my father and his sister (and eventually their younger siblings) walked over a mile to the church for mass and then home for breakfast, and then walked back to the village for school. During confession, the curé condemned sins so loudly that those who were waiting heard everything. If a young woman confessed to losing her virginity before marriage, he yelled, excoriating her in such precise terms that the entire congregation knew the place, time, man, and general mood of the deflowering.

Once, after morning confession, my father’s older sister realized that they would not have time to return home for breakfast, and not wanting to endure the ferule of the nun who taught her class, she skimped on Hail Marys to take my father home for breakfast. Curé Félix-Jean noticed and not only berated her but made her remain in penance until after school began. She and my father went the day without food and were also punished by the nun who taught their class.

The story my father told of his ultimate disillusionment occurred when he was only seven, during a Sunday Mass sometime near the end of the Second World War. In the village, a man had left his wife, and a woman her husband, and the two had moved in together into a small house not far from the church. Curé Félix-Jean was so incensed about this immorality that he preached fiercely on the sanctity of marriage and then on God’s wrath against sinners. He told the congregation that the couple should burn. They all knelt, heads bowed, as he commanded them to pray that the fire of heaven would descend and destroy the two sinners.

The image he painted was so clear, so compelling, that my father slipped from the pew where his family sat near the door and let himself out of the church, escaping the attention of the congregation. Before his mother could notice his absence, he was running to the house of the condemned couple. He crouched on the forest side and peeked into their window. The man and woman sat at the table, having breakfast and talking.

“They looked happy,” he said. “There was no fire. I kept waiting for the fire to come down and burn them, and I was worried that I was too close to the house and might get burned up too. But when the fire didn’t come, I knew that fucking priest was a fake.”

The next nine years were shaped by his determination to leave. The revelation, as simple as it was, had left him certain, he said, and free. He blamed the Church for selling out the impoverished French Canadians to wealthy industry and told me how, on election day, men in suits arrived and gave the children pop and each fisherman five dollars to let the strangers cast their ballot for them. This, too, he insisted, was the fault of the Church.

My father’s last visit to his family was in 1967, after a significant bank heist and shortly before a seven-year prison sentence of which he would serve half. Thirty years later my aunt told me how, during that stay, Curé Félix-Jean died.

“Edwin hated the curé,” she said. “We joked that maybe Edwin killed him. But that’s silly.”

• • •

In the 1960s, the Quiet Revolution released decades of pent-up desire for change, the exultant anti-authoritarian energy of the time pouring into Québec. Much of this was due to the modernization of communications and the facility with which ideas were transmitted, but the death of Maurice Duplessis in 1959 was the catalyst. Duplessis, often simply called le chef, dressed in black and ruled (this being the better word than governed) from 1936 to 1939 and 1944 to 1959 – almost twenty years in total, a period sometimes referred to as la Grande Noirceur, “the great darkness.” The Roman Catholic Church supported his programs, at one time employing the slogan, Le ciel est bleu; l’enfer est rouge – “heaven is blue, hell is red,” blue being the colour of his party and red being that of the Liberals against whom he ran.

In 1960, the province elected the liberal government of Jean Lesage, whose slogans were Maîtres chez nous and Il faut que ça change – “Masters at home” and “There must be change.” The revolution had no precise beginning or end. The desire for new ideas and freedoms already existed, though they had long been suppressed. French Canadians wanted a stronger place in Canadian society, as well as social, economic, and political advancement. Within a decade the province was transformed: institutions were secularized and nationalized, ministries created to replace Church-run institutions, private and foreign interests no longer dominated trade. The birth rate dropped to the lowest in Canada, and Francophones distanced themselves from both Canada and the Church. By the 1970s, they no longer referred to themselves as Canadiens français but as Québécois.

By this time, my father had embarked on his decade of crime. While he was learning safecracking and pulling armed robberies, Québec was becoming polarized, separatism was taking hold, and the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) was growing. Operating out of Montréal and trained in Palestine, terrorist cells intended to start a Marxist-Anarchist revolution and establish independence and a workers’ society. Between 1963 and 1969, an average of one bomb was planted in Québec every ten days. The FLQ targeted businesses, banks, armoured cars, McGill University, and the homes of wealthy English families. They destroyed a statue of Queen Victoria and set off a bomb in the Montréal Stock Exchange, injuring twenty-seven people. A group of FLQ members were even apprehended on a mission to destroy the Statue of Liberty. The only similarity between this episode of history and my father’s life is the FLQ’s bank holdups, though I’m pretty sure the perpetrating members didn’t run off to casinos afterwards.

In October 1970, what was to be termed “the October Crisis” occurred. The FLQ kidnapped James Cross, the British trade commissioner in Montréal, and, five days later, Pierre Laporte, Québec’s popular Minister of Labour and Immigration. The Québec government requested the help of the Canadian Armed Forces, and Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau proclaimed the War Measures Act. Civil liberties were suspended and hundreds arrested. Troops lined sidewalks and roofs, and tanks roamed the streets. In an arena, three thousand students gathered in favour of the Front de libération du Québec, chanting F-L-Q. Columnist, politician, and future premier of Québec, René Lévesque, wrote his approval of the government’s response in the Journal de Montréal: “L’armée occupe le Québec. C’est désagréable mais sans doute nécessaire aux moments de crise aiguë.” (“The army has occupied Québec. It’s unpleasant but probably necessary in times of acute crisis.”)

The day after the War Measures Act was invoked, the FLQ killed Pierre Laporte and left his body in a car trunk near Montréal. James Cross was later released, and in return his kidnappers were allowed to leave the country. Several of the FLQ’s leaders were exiled to Cuba. Around that time, my father’s own period of chaos and uncertainty came to an end, and after incarceration for a bank burglary in Hollywood, he was deported back to Canada.

History and his untraceable journeys leave me trying to understand his ideals. He wanted success, to live like the wealthy English, but this longing grew in absentia from the culture that had created it, and lasted well after that culture had changed. When he spoke of Québec, he did so with distaste, telling me that it was poor and violent, that priests ran everything, though he sometimes admitted that it was no longer the same. He’d seen it changing when he’d last visited his family during Expo 67.

In the final year of his life, he told me many stories, among them one about two brothers splitting wood in his village. One brother would set a piece on the block and the other would split it. They had been working for a while when, just as the axe was coming down, the first brother put his hand under the blade, yelling “Stop.” The axe took his hand off and embedded itself in the wood. The brother later claimed that the face of Christ had appeared to him in the wood grain, more perfect and beautiful than any image he’d seen in church. The curé himself went to look at the wood. After prying the axe loose, he washed the blood off, but saw nothing. The brother died from loss of blood, and at his mass Curé Félix-Jean spoke of the beatitude that carried him away, Jesus having called him to his breast.

Telling the story, my father sounded distant, dreamy even, as if he believed it, as if the story and the act of telling a story, of imagining, still had power over him, and then his tone changed.

“I grew up with that guy,” he reflected gruffly, but quietly, as if afraid to undermine his story. “He didn’t seem any better than the rest of us.”

• • •

History forgives. Reading through records of the past, I have found a gradual absolution, a few explanations for centuries of hardship and brutality. Framed by these stories and in the light of so many lives and years and changes, humanity seems less disconnected and therefore less mysterious, and yet the mystery of individuality remains, despite our insignificance.

My mother once told me that in the first year she and my father were together, they lived out of a van and drove across Canada, and finally through Québec. They followed the southern coast of the St. Lawrence, passing through one community after another until they reached his village. He had grown a large beard and said he would be unrecognizable to his family, and yet he refused to stop. Hearing this story, I tried to sense how he had felt seeing his home, the coast of his youth, the village where he grew up and where his mother lived – and not stopping.

In thinking about this, I slowly began to understand that his journey was not a return, but rather an extension of his flight and quest. In this, he greatly resembled the historical figures who preceded him: the travellers, the sailors and hunters who left France and voyaged to other lands in hopes of riches, who gave up their homes and families, many of them never to return – and whose children continued to journey: to the Francophone cultures of the Great Lakes, to Oregon or California or Maine, down along the Mississippi to la Nouvelle-Orléans, or west among the Métis of Manitoba.

More and more, he has seemed emblematic of a certain past and less of an anomaly. He loved to swear and tell stories, and in both activities I see the presence of an older Québec. The profanity there responds to the Church, an eighteenth-century expression of frustration and a form of resistance against the oppressive clergy – Québec French uses expletives derived from religious terms: tabarnak and câlisse and ciboire and ostie and crisse (corresponding to tabernacle, chalice, ciborium, host, and Christ), among many others. The Québécois take not only the Lord’s name in vain, but all of his utensils and trappings and family as well.

Reading books of French Canadian folktales, I found hints of my father’s humour and adventures in the deeds of the trickster, Tit-Jean, “Little John,” who fooled the devil on numerous occasions while being devilish himself. The more I read, the more I wondered how many of his stories were inventions or exaggerations inspired by those old tales. Though he’d tried to cut himself off from his past, it had lived more fully within him than he realized: his journeys and words were echoes of resistance.

The model for my father was precisely the sort of man the Church had spent centuries trying to tame and on which it had nonetheless depended for its spread. Missionaries followed trade, trying to domesticate the very people who opened the path for them. They needed the brave and self-sufficient voyageurs, and so wanted those men to need them in return. French Canadian stories and profanity are the negotiations of an older culture with a new repressive authority, the traces of who a people were before or have always been, and the encoding of old values and narratives into new expressions. The trickster becomes all the more necessary when faced with such authority. He is a reminder of the people’s strength, one of those who stands against the rich and thumbs his nose at the puritanical. The heroes of Québec’s Wild West, its coureurs des bois, could not be so easily forgotten.

Gradually, I have come to understand that my father’s working man’s humour was that of the trickster who wagered the world on his wits. The seductive daughter of the idle and obese rich man returned in his stories as models and actresses in casinos and at resorts. The devil himself was recast as a diabolic pimp paring his fingernails beyond the glitter of the dance floor. And the harsh priests found themselves embodied in stern policemen and prison wardens and bank owners. The trickster, the handsome criminal, eyes impassive behind sunglasses, straightened his tie before picking up a gun.

• • •

Until the end of my father’s life, he and I lived in a state of almost perpetual conflict. Years later, when listening to me describe my childhood, my aunt once said that Québec had changed, but my father had not – that he’d raised us as if still living in Québec before the days of the Quiet Revolution. He hated school, and our greatest conflict grew from this: his insistence that I quit when I was fifteen and my insistence that I continue.

The themes of the talks and conflicts between my father and me lasted until the final weeks of his life. He wanted me to drop out of college and live with him. He was now using heroin regularly, and he told me that he hoped to end his life in this way. In his voice, I heard the desperation for escape and change that must have always been there for him, his need to leave and be set free, far from whatever haunted him. He asked me to research religions and tell him what they said about suicide and the afterlife, about what was next and whether it was good. The North American traveller thinks of riches and a new life, and my father was still dreaming of a better place, just one beyond this world.

We often talked all night. He told stories and then asked what I’d learned about Buddhism or Hinduism. When I would share what I’d read, he would interrupt to say, “Drop out of college. You don’t need an education. Education is useless. I never needed one. Come work with me. We’ll go fishing.”

“I can’t,” I told him, and continued to explain the beliefs of each distant culture, their punishments and heavens.

Shortly before Christmas he shot himself up with heroin and drank a glass of antifreeze. Two years later, I found the strength to return to Vancouver to get his ashes and his few remaining possessions. There was a single plastic suitcase with a nylon and acrylic jacket and a pair of jeans and a few shirts. In the jacket’s inside pocket were three pieces of paper: a recipe for homemade beer written on several notepad sheets, in a woman’s neat hand; the corner of a page torn from Playboy advertising a calendar with a photo of Miss January, a naked blond arched back onto her shoulders; and a pamphlet from a church, with a New Testament verse and a place to sign one’s soul over to Jesus – signed by my father.