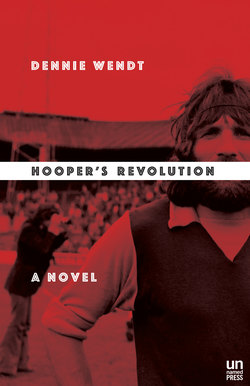

Читать книгу Hooper's Revolution - Dennie Wendt - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFOUR

“There are a great many players of solid English pedigree in the American All-Star Soccer Association” is what Danny repeated to his dad over a swifty two hours later. “So said the chairman anyway.”

“The American All-Star Soccer Association? A mouthful, innit?”

“I know how it sounds.”

His father wrinkled his brow in hard thought as he worked it out. “The...AASSA? Of the USA?”

“That’s it, Dad. The AASSA. It’s the New York Giganticos’ league. With the Brazilian and the Dutchman and all those World Cuppers they’ve signed up. A decent league, I’m told. McCoist, from that great Rangers team that won the League Cup in ’72, plays in Toronto with a bunch of Serbians. Logan down at Southside Wanderers, he got his start somewhere in Texas. And Sweet Billy Robinson—Sweet Billy Robinson, no less, Dad—he’s playing out his drunken career in Los Angeles.”

Danny’s dad’s left ear twitched, indicating a desire for another round, so Danny ordered two more and then continued: “There’s an entire team of Ukrainians in Chicago I think. Or Poles. The Butchers they’re called. Butchers. You know what the chairman told me after telling me all this?”

His dad dipped his head. He had no idea what the chairman had told him.

“‘Go have a laugh, Danny. Have yourself a laugh.’”

Danny folded his arms over his big and strong body and looked at the wall behind the bar. There was an East Southwich Albion team photograph hung there, 1971–72. The blue-shirted Royals, in their post–“Let It Be” haircuts and Elvis sideburns, looked a grim bunch, not at all happy to have their picture taken that typically overcast day at the Auld Moors. Looking at it made Danny’s heart tighten. That picture, of that barely-avoided-relegation-from-the-Third-Division version of East Southwich Albion AFC, had been the last team picture of the Royals not to contain one Danny Hooper. The next year’s team would feature a young, tall, semi-bulky center back with limp hair that hung to his shoulders like a hood, toothy smile asymmetrical and eager. They called him a center half sometimes, but he was a back in every way a player could be a back. He hadn’t grown all the way into his frame—and hadn’t yet sorted that beard—but he’d made the squad on height and potential. He hadn’t gotten in more than three or four matches that season—just didn’t have the body for it yet—but it had been a glorious campaign as far as he was concerned, the culmination of his boyhood dreams (minus a trophy). He had become a Royal, a real one, had earned first-team privileges, had run out on the Auld Moors’ lousy pitch before the club’s true followers, had taken his halftime tea with men he’d watched for years. The people of East Southwich knew him now, and he knew them. He had not reached the mountaintop, had no medals, no cups, but he could see them from where he stood. East Southwich Albion was only a year or two from promotion to the Second Division, Danny could feel it—and once you’re in the Second Division, things can happen, things can happen.

But not anymore.

His father wanted to know what team he’d be playing for in the American All-Star Soccer Association, and Danny said, “The Rose City Revolution they’re called. In a place called Oregon. They’ve a decent following, says Aldy. Out on the West Coast.”

His dad’s eyes asked, Now where in blazes is Oregon?

Danny sat still for a moment, still looking at that old team photo. He said, “It’s out by California. ‘Rose City’ is a nickname. Town’s called Portland. Apparently, they’ve taken to football.”

His father and Vic the bartender, who’d drifted down to listen, were now both wordlessly asking, You’re doing what?

“Joining the great American Experiment, I guess.”

Vic said, “I’ve seen photos of those games, Danny, in magazines and the papers. Unless the Giganticos are playing, nobody goes. Nobody’s goes, me boy. Empty seats by the mile, ’orrible kits, them plastic pitches. It’s a wasteland, Danny. A football wasteland.”

The men of the East Southwich Hoopers looked at Vic as if his job was to pour the pints. Danny said, “That may be, Vic, old man, but I’ll be making twice what I’m making now, and you know what the last thing out of Aldy’s mouth was?”

Vic said he had no idea.

“Say hi to the Pearl of Brazil.”

Nobody said a word after that, and Vic turned to pour another round.

Danny opened the door to his flat and walked to the kitchen. He grabbed an empty glass from a cupboard, filled it with water, leaned back against the counter, and tipped it back. He wasn’t thirsty; he just couldn’t think of anything better to do. He wasn’t even sure what he was now. He was neither thirsty nor hungry, neither angry nor sad, neither East Southwich blue nor... anything else yet. Didn’t even know what colors the Rose City Revolution wore. He felt purposeless without his club, empty without the validation of the rest of his back line, the mad blue mob behind the goal, the misguided but well-intentioned encouragement of Aldershot Taylor.

He had no mental picture of Oregon—was it named after a shape? What could an oregon be? He had no real sense of what the American All-Star Soccer Association was all about. He knew about the Giganticos—everyone knew about the Giganticos. But other than them, all he knew was that the league was a United Nations of football misfits, a circus of decaying oldsters seeking quick end-of-career paydays and free booze, young English League castoffs trying to prove Old Blighty wrong, one-eyed goalkeepers, hordes of Eastern Europeans and overrated Latin dribblers, random job-seekers from Haiti, Kenya, Korea, Australia, the odd plucky Yank. He’d seen those pictures Vic had been on about: garish uniforms and all those empty seats, acres of them. There were those pictures, and then there were the pics of a certain beloved Brazilian. Lots of those. No empty seats in those photos.

He had only ever wanted to win a championship, a trophy, a medal of some kind, any kind. Now he was out of the FA Cup, out of the English League. (Ninety-two teams, at least twenty men per team, probably more, that’s... 1,840. Round that up to two thousand. Two thousand spots in the League, and not a one for Danny, no matter how big, no matter how strong.) And off to a league that already had its trophy spoken for by the Pearl and his Giganticos.

He was alone, still trophy-less, and confused as hell as he let his sore, bruised self drop down into one of two chairs in his kitchen. He closed his eyes.

When he opened his eyes, he was no longer alone.

“That is a glorious black eye, Mr. Hooper, if I may say so.”

What the hell? Danny thought.

“Other than that small detail,” the intruder carried on, “how are you this fine English day?”

A man sat across from Danny, right there in his kitchen. Where he had come from, Danny did not know. The man wore a black suit with a thin black tie. His suit was neither in style nor a good fit for his gaunt frame and paunchy middle. The intruder had spoken with the confidence of a fitter man in a better-fitting suit.

Well, Danny thought, might just as well have a strange man in my flat. Why not? But while his thoughts swirled, he was struck dumb.

The visitor went on, unruffled by Danny’s silence: “It’s all right, my boy. I am aware that you haven’t been speaking much lately.” He paused and took a cigarette pack from his breast pocket, dislodged one, lit it, inhaled, and kept talking, easing out a genteel cloud of smoke to swirl around his head. “Talk, talk, talk,” he said, describing a parabola in the air with his cigarette. “Everyone thinks everyone wants to hear them talk, don’t they, Danny? Annoying, really. I try not to say more than I must... got it from my father. I think I heard the admiral utter approximately one nice clear thought a week. A reticent sort, and I quite admired him for it. Ah, but listen to me, Danny. Me, of all people. Going on and on. That’s what happens when you don’t talk, Mr. Hooper—I end up rattling and prattling, don’t I?” He laughed and narrowed his eyes shrewdly at Danny: “It’s a good trick you have there.”

The man was maybe ten years older than Danny. Just early thirties, Danny thought. His face was the pasty color of the usual East Southwich sky—white with hints of blue and gray, like the exhaust from a car engine begging to die, or thin milk.

Danny thought, Well, I could strike him. That would probably be the smart thing to do. Just punch him in the nose...

And as Danny had the thought, some twitch or itch or inkling triggered something in the intruder’s training or instinct or muscle memory, and the man in the suit said, “Oh, no, noooo—Danny. You don’t want to do that.” The man laughed a wheezy chuckle and said, “I should say, I definitely don’t want you to do that. You’re a far stronger specimen than I am, Danny, and such a terrific athlete. There’s little chance I’d be able to fight back. I do have a few techniques I’ve been anxious to apply on an actual subject in the field, as it were, but still—I saw what you did to that poor lad from Dire Vale, and believe me, I have a full and deep understanding of just who qualifies as big and strong in this... well... kitchen.” He looked around the space and said, “My gracious, man, do you never—”

“Who the hell are you?” Danny said in a burst of anxiety and panic and frustration.

The man laughed. “Ah, yes. How rude of me. I’ve been terrible.” He shoved his hand across the table, and said, “Danny Hooper, late of East Southwich Albion Association Football Club, you may call me...Three.”

Danny relaxed for a moment in the face of this preposterous announcement, relieved at the thought that he could either be dreaming or have been transported to some alternate reality that would soon cease to be, and he would soon be back on the training ground at the Auld Moors, rolling his eyes at something that had just escaped Aldy Taylor’s mouth or trying to decipher an instruction from Mumble McCray.

“I see,” Danny said. “Your name is... Three.” Danny walked to the sink, refilled his water glass and took a sip from it. “Go on, then, Three. Explain.”

Three attempted a smile, but it came unnaturally and only made Danny more certain that he was a weaselly character, an untrustworthy annoyance. “I reckon you’ve opened your mind to the many reasons I may be here in your flat, and you have yet to demonstrate a commitment to physically attacking me. This is a relief for obvious reasons, but it also paves the way for us to come to an agreement upon the circumstances which will hold when I leave your residence, my dear man.”

“Maybe I will attack you. If you keep on talking like that. I’m a dangerous and unstable person. I’ve proved that much, haven’t I?”

“You may be all of that, but I don’t believe you’ll attack me. Not in my heart do I believe such a thing.” He placed his hand across his breast.

“Explain yourself... now,” Danny uttered, clenching his fists.

“Of course, of course. All business.” Three waved his cigarette again. “Let us indeed cut the pleasantries just a bit short. I, Danny, am in possession of your plane ticket to America.”

Danny winced as if he’d been hit. “What? Who the hell are you?”

“Yes, yes! Now I have you! Very good, Danny! Everyone comes around in time, in time. And you’re a quick one! Well, I’m hardly surprised. Most of the athletes are quick, in one way or another. Very good. Now then, Danny, I have arrived at the point in the proceedings where I explain that I work for the Queen. The Queeeeeen, Danny. I do love saying it. Her Majesty. Her Royal Highness. The Crown. I work for England, laddie. Actually, I work for the United Kingdom—the whole bloody thing. Grrrrrrrreat Brrrrrrritain.” He rolled his r’s. “I am, in point of fact, here this very day on your behalf, to protect you, Danny, and those many millions like you.”

“Listen—” Danny ventured, but found himself cut off.

“And here’s where you come in, dear boy. You are going to help us protect the great British we—the greatest empire the world has ever known—from some genuinely bad doings. And the Americans too. You’ll be protecting them as well. And the Western world, really.”

It occurred to Danny that this man was mad. And then he really thought it through, and right at that moment, he realized that the fringe benefit of Three’s bothersome presence and inability to shut his piehole was that Danny, for the first time in his post–East Southwich Albion existence, cared about something other than the reality of being an ex-member of East Southwich Albion. For this Danny was grateful. He leaned toward Three, put an elbow on the table, formed his hand into the obvious sign for give me a cigarette, and Three smiled. Soon, they were both smoking.

“Now,” Three said, “football in America—soccer... I can barely even say the word—awful, awful word—is as foreign as passable curry and decent ska. Yes, all right, it has slight followings here and there, in the ethnic pockets, but mostly, Danny, people over there hate it. Simply hate it. They think it’s a Commie sport. Collectivist, you know. All that passing. And all those short shorts and high stockings and strange names and no hands. The Americans, most of them anyway, just don’t trust it. And draws... tied games... they just hate ties. They’ve banished them, actually, the Yanks have. Did you know that? Ah, but you’ll see, you’ll see. In any event, football—soccer—isn’t at all American and they don’t bloody like it.”

Danny smoked and waited.

“Well, Danny, do you know what abhors a vacuum, other than nature, of course?”

Danny gave Three the same look he’d given that Dire Vale winger right before he probably ended his career.

Three said, “All right then, I’ll tell you: Communism.”

Communism? Danny thought. This is about Communism? Communism abhors a vacuum? Since bloody when?

“That’s right, Danny. Communism. While almost all of America, including its government, the CIA, the FBI, and every home-on-the-plains sheriff with a nice big gun, has been ignoring the world’s game, even as the world’s game carries on right under their noses, would you like to hazard a guess who hasn’t?”

Danny scarcely followed. “Who hasn’t what?”

“Who hasn’t been ignoring the American All-Star Soccer Association? The bloody Communists, Danny! The Red Menace! The whole league is a den of Marxist iniquity.”

“All right then,” Danny burst out. “That’s it! That is bloody it.” Danny stood abruptly and reached for Three’s collar. “Time to go back to whatever hospital you’ve escaped from.”

Three ducked—calmly, as if he’d done this kind of thing many times before—and reached for a satchel on the floor by the table. “Calm yourself, lad.” He removed a manila envelope inscribed with Danny’s name and handed it over. “Inside you’ll find your plane tickets, a Rose City Revolution match programme, and a little stipend.”

Danny stood holding the envelope, still in a position to take a lunge at Three, and Three still looked at Danny as if an attack might be forthcoming. But Danny took a few breaths, reminded himself what happened last time he let rage guide his actions, and sat back down.

“The Russians are using the AASSA as a Cold War communication channel, my son,” Three said as Danny reviewed the contents of the manila envelope. “They’ve loaded up all these teams with Hungarians, Bulgarians, Croats—the Chicago team used to be called the Ukrainians, for Christ’s sake. The Chicago Ukrainians. There’s a team called Red Star Toronto that’s as Serbian as they sound, and the Colorado Cowhands are a front for a Romanian organization that pretends to be raising funds for orphanages—the rot really has set in, Danny. They pass if off as cultural exchange if anyone notices at all. Red Star Toronto. Honestly. It’s like they’re not even trying to conceal themselves. Of course that’s Canada, but still and all. And don’t even ask about the Cubans in Miami. Cubans in Miami. Do you know how much Cubans care about football?”

Danny had taken Three’s question as rhetorical, but Three lingered for an answer. “Do you know?”

Danny had never heard of any Cuban footballing achievement or even of a Cuban league, so he ventured a timid, “Well, let me hazard a guess, Three. Not very much?”

“Not very much? How about not at all? Castro almost played for the New York bloody Yankees, Danny—all he cares about is baseball. I’d lay money your East Southwich boys could beat the Cuban national team nine times out of ten. But you run out a team of Gonzalezes, Garcias, and Hernandezes with ‘Florida’ on their kit and Americans think they’re watching Latin football. The few that care, of course. Which isn’t many. The Flamingos of Florida Professional Soccer Club is Havana’s U.S. office, for Christ’s sake, and no one’s paying it any mind down there, Danny. No one.”

Three took a deep drag on his cigarette, as if to calm himself down. “All right then,” Danny said. “Let’s say I’m following. I’m in no great hurry, mind, but cut to the punch.”

“We’ve connected with a few of the smart ones over there, who you’ll soon meet, dear boy, but you say ‘football’ to most Americans and they think you’re talking about something else. You say ‘soccer’ and their eyes just go blank. They fall asleep at the very sound of the word. It’s like an instinct. Pavlov’s dog. ‘Soccer’: sleep. Remarkable phenomenon.” He tapped the ash of his cigarette into Danny’s water glass. Danny winced at the affront, but Three said, “These Communists are bloody brilliant. I’m impressed. We all are.” He gave Danny a stern servant-of-the-people frown and said, “Danny, your country needs you. And, well, you need to get out of the country. So... to put a fine point on it... you’re going over to, well, to fight Communism.”

Danny got up, got himself another glass of water, returned to the table, pushed the ashy glass toward Three.

“From what I’m told, the Rose City Revolution is already full of Englishmen,” Danny said. “What’s this got to do with me? Just use one who’s already there.”

Three smiled, knowing he was making progress. He looked directly at Danny, sucked in hard on the shrinking butt of his cigarette, and said, “The Soviets are vicious, godless, barely human, and awfully frightening, but they’re smart. Here’s what they’ve worked out: football is the most important game in the world. It’s the most important anything in the world. More people love football than love Jesus or Muhammad Ali or Buddha or the Rolling Stones, and a lot of the people who love all of those things love football more. If you want to send a message, and you want to reach the biggest possible audience, you send it through football.”

Danny had never thought of this, but he knew it was true; he was surprised to find himself agreeing with Three.

“And if you want to plan something—something big—through football... or anything else,” Three continued, “you plan for it to happen in America. That’s the arithmetic.”

This Danny thought was less obvious, and Three noticed.

“Come on, think about it: you can mix and match nationalities as you can nowhere else on Earth, you can humiliate the Yanks on their turf, and if you pull it off in New York City... the media of the world is right there, just waiting for a big story. And if they can pull off something big enough, the message will be that the Soviets are winning. That they can sneak anything they want right under the Americans’ noses, that they can do... anything... they... want.”

Danny shuddered. He hated thinking it, but he thought Three might be onto something.

“The message to the entire planet will be that the future is bloody Communist.” He stubbed out his cigarette. Danny could tell that Three was proud of his little presentation, that it was well rehearsed and he’d done it just as he’d hoped.

“But what do they want to pull off, exactly?” Danny asked.

“That’s what we’d like to know, lad. They’re planning something in America. It’s 1976. The bicentennial. They just can’t get enough of celebrating being rid of us, you know. Still prattling on about it two hundred years later. Anyway, my boy, we believe Graham Broome may know what it is. We think he’s one of them. Used to get away with calling himself Labour and getting worked up every time the coal miners went on strike. I’m not talking about ‘Graham Broome hated Edwin Heath.’ I’m talking about a serious mover and shaker in left-wing circles, anti–Vietnam War, the whole monty. We believe he’s helping them somehow. Somehow you’ve got to help us work out.”

“Everyone hated the Vietnam War,” Danny said.

“You’re not thick, Danny. You know what I’m on about. We have intelligence that Broome has helped pass information from a Bulgarian playing for the Seattle Smithereens to the Montreal Communards. That’s what the team used to be called—the bloody Communards. Anyway, from there the trail goes cold. We’re not even sure he knows he’s doing it—they may have just found a sympathetic ear and they’re using him, they’re using poor Graham Broome. We need you there. We need to know their plan.”

Danny stood up from the table. He towered over Three, and he could see he frightened the besuited bureaucrat. Danny said, “Why me? Two thousand players in the Football League. Why me?”

“We’ve been watching you, Danny. You’re perfect. You’re single. We need a single lad. We couldn’t take a First Division player—too conspicuous. And we’d like someone whose game is distinctly English but who has an appreciation for the Continental and even Latin games—you’re going to have to mingle with players from all over the world, players who don’t think your English accent automatically makes you a world champion. Aldy Taylor tells us you’re a sucker for that Dutch Total Football claptrap—you’ll fit in over there. And you’re smart. A clever lad. In a good way.”

“And what if I say no?”

Three sighed. “If you stay in this country, you won’t be happy with how you stay in this country. And now we know what you can do to another man in the space of a second or two. We may need that.”

Danny didn’t know which of the two sentences to respond to first, but before he decided, Three decided for him: “I’ve seen that look before, and that look is Would you really? and the answer, my dear boy, is I’m fighting international Communism. If making you pay for what you did to that little Welshman would help in even the slightest, smallest, most miniature way, then yes. Yes, yes, and yes.”

“All right then,” Danny said.

Three dropped his cigarette to the tile floor of Danny’s flat and said, “That’s what I came to hear.” He reached across the table to shake Danny’s hand. Danny reached back. The men shook.

“I will call you in your hotel then in your Portland flat whenever I need to speak with you. No matter what you hear, if it sounds like something—anything—to you, it will surely sound like something to us. Tell me everything. If you ever have anything to report that feels too sensitive to say over the telephone, you’ll tell me your hamstring’s shot. Should I hear that, I’ll reel off a series of league scores that make up a number that you’ll use to call me from a pay phone. Do you understand?”

Danny said nothing.

“Do you understand me?”

“I get it, I get it,” he murmured.

“Now, listen. I can appreciate what we’ve done to your life. Two days ago you were stepping out on that pitch thinking you were about to help your boyhood club advance to the Fifth Round of the FA Cup, now... all of this. But your country really does need you—and besides, Communist Graham Broome thinks you’re the missing piece for his side. He thinks with you there he can get the Revolution all the way to the Bonanza Bowl.”

“The what?”

Three laughed. “Erm, yes, well—that’s what they call their big final over there. The Bonanza Bowl. I know, I know. But the Americans do love a catchy name and a grand spectacle. It always gets a pretty good crowd of curiosity seekers. Scheduled for New York this year. The Giganticos will be there, of course.” He sized Danny up and said, “Listen, son, go on over there, help us stop this sinister plot, whatever it is, and try to win yourself something. Get to the Bonanza Bowl. You’ll be a hero times two by summer’s end.” Three looked at Danny and said, “For club and country, hmm, old boy?”

Danny raised an eyebrow and said, “For club and country.”

Three turned, grabbed his satchel, and walked himself to the door. “Talk soon, Hooper. Travel well, my boy.” He closed the door and left Danny in the half-dark silence of his flat.

Danny closed his eyes, shook his head, considered crying. His mind was both blank and overcrowded with everything that had been crammed into it over the last few days. The FA Cup. The chairman. Aldershot Taylor. America. Three. The Rose City Revolution. Oregon. The Russians. The Giganticos. The Pearl himself. Then he opened his eyes and stood up.

“The Bonanza Bowl,” he muttered. “The Bicentennial Bonanza Bowl even. What a load of rubbish.”