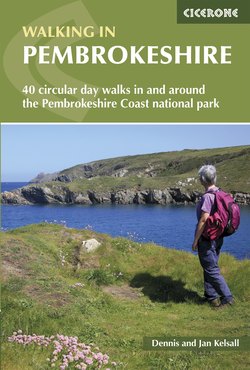

Читать книгу Walking in Pembrokeshire - Dennis Kelsall - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

The view across Cwm-yr-Eglwys bay (Walk 17)

Like the Finisterre of Galicia and the Land’s End of England, Pembrokeshire (or Pen-fro) has the same meaning for the Welsh, ‘the end of the land’. The southwestern-most tip of Wales, it presents a similar outline to the open seas as its more southerly namesakes, with ragged peninsulas reaching out towards the setting sun. Settled in the earliest times, these drawn-out strips of habitation share other things too: the roots of their Celtic culture, vividly portrayed in the enigmatic remains of ancient settlements and sacred sites; the commonality of native language and a passion for storytelling, legend and song. Pembrokeshire is a place of great dramatic beauty, where land and sea stand in hoary confrontation, with bastions of craggy cliffs pushed back behind sweeping bays, and innumerable tiny coves separated by defiant promontories.

But not everywhere is the demarcation clear. Tidal estuaries and twisting rivers penetrate deep into the heartland, where steep-sided valleys and sloping woodlands climb to a gently undulating plateau. The countryside is chequered with a myriad of small fields and enclosures bound by herb-rich boundaries of stone, earth and hedge. Even higher ground rises in the north, not true mountains perhaps in the expected sense, but bold, rolling, moorland hills from whose detached elevations the panorama extends far beyond the confines of the county’s borders.

The legacy of the past

Today, much of Pembrokeshire basks in rural tranquillity with few major roads or large towns, yet it proudly boasts a city, the smallest in the land, which grew around the memory of David, the patron saint of Wales. Predominantly, however, the county is a landscape of small villages and scattered farming settlements, their history often told in ancient churches, ruined castles and the relics of abandoned industry and transport. Even more ancient are the remnants of prehistoric earthworks and enigmatic standing stones, while clues to the past can also be found in the very names of places and landscape features.

St John’s Church at Slebech (Walk 27)

Until the beginning of the last century, Pembrokeshire was less ‘land’s end’ and more ‘gateway’, not on the periphery but rather at the hub. Before the coming of the railways it was a maritime land, connected by sea routes to Britain’s great ports, Ireland, northwest Europe and far beyond. Despite the dangers and vagaries of the sea, its unpredictable weather and rudimentary navigation, travel by boat around the coasts was relatively commonplace, and for bulky or weighty cargoes it was the only economically practical means of transport. This allowed the exploitation of Pembrokeshire’s natural resources such as slate, stone and coal, as well as its rich farming land, and many landings and coves around the coast and along the tidal inlets were once hives of industrial activity.

Over five thousand years ago there was an established trade with Ireland, bringing precious gold and copper from the Wicklow Mountains to the main centres of Bronze Age civilisation in southern Britain on Salisbury Plain. For the Celts, too, the sea was a highway, encouraging migration, the spread of ideas and the exchange of artefacts and produce. After the Romans left Britain, Christendom established itself along those very same routes and Pembrokeshire assumed an importance comparable with other notable devotional centres around the land, such as Iona off Mull and Holy Island off the Northumberland coast. Indeed, St David’s headland is one of the places from which it is claimed that St Patrick embarked on his Christian mission to Ireland in AD432, and by the early centuries of the second millennium, such had become its importance that two or three pilgrimages to St David’s had the same spiritual standing as a journey to Rome or Jerusalem.

The Vikings were less welcome visitors, but the Welsh never lost the thread of their independent culture, even with the later settlement in at least part of Pembrokeshire by the Normans. Under them, important trading ports developed such as Tenby and Pembroke, protected by great castles that sought both to establish authority over the land and define a frontier line of defence. Political quarrels with Spain and, later, France saw the strengthening of coastal fortifications, most spectacularly around the vast inlet of Milford Haven, where naval dockyards exploited one of the world’s finest natural harbours, and which Nelson considered second only to Trincomalee in present-day Sri Lanka.

Manorbier Castle (Walk 2)

The 19th-century heralded a period of massive and fluctuating change. The industrial upsurge elsewhere in Britain created a seemingly insatiable demand for raw materials, which immediately provoked a dramatic upsurge in quarrying and mining right around the coast. But hard on its heels came the development of the railways and the advantage of coastal access rapidly diminished in favour of places served by the new arteries. Quarries such as Porthgain and the coal mines of the upper Daugleddau quickly boomed but then declined, unable to compete with the previously unimaginable speed, ease and low costs of rail transport. But, while much of this corner of Wales was ignored, the early railways found in Pembrokeshire the quickest route from London to the western seaboard. It created a link from the first landfall with suitable harbour facilities for Irish and transatlantic shipping, whereby passengers, mail and cargo could reach London in the shortest possible time.

Under the engineering genius of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, new ports were built at Neyland and Goodwick. But even here the hoped-for prosperity was short-lived, an economic disappointment repeated during the latter part of the 20th century when the oil industry’s ambitions for the development of the Haven declined. Yet the people of Pembroke are nothing if not resilient; liquefied natural gas now rivals oil as the main import to the Haven terminals, surrounded by a new generation of developing light and high tech industries.

The national park

Remaining quiet and unhurried, Pembrokeshire is largely uncrowded by either residents or visitors, and has been spared much of the adverse consequence of the urban and industrial developments of recent decades. The unspoilt magnificence of its coastline, almost 200 miles (320km) of cliffs, bays, beaches and inlets, was recognised in its unique designation as a coastal national park in 1952. Only the industrial areas lining the Haven, and a short stretch abutting the Irish ferry terminal at Goodwick, were excepted. Many of Pembrokeshire’s other areas of outstanding beauty and important natural habitat were incorporated too: the Preseli Hills, the Gwaun Valley and the higher tidal reaches of the Daugleddau. But outside the park boundaries the countryside is not to be ignored either, for there is an abundance of natural woodland, hidden valleys and pleasant riverside to explore.

Forest covers the lower slopes of Foel Cwmcerwyn (Walk 20)

Pembrokeshire’s coast

For the rambler, Pembrokeshire is nothing short of pure delight. Long-distance walkers will already know it for its 180-mile (290km) Coastal Footpath, arguably one of the finest routes in Britain. But its ready accessibility and serpentine geography ideally suit it for those with more modest ambitions too, and many of the most beautiful and dramatic sections provide splendid part- or full-day excursions. From a gentle 1-mile stroll to a more challenging 12-mile hike, there is something for everyone in walks that follow the tops of precipitous cliffs or delve into secluded sandy coves. Examples of just about every type of coastal feature are explored, from cavernous blowholes to natural bridges, from solitary stacks to evidence of glacial erosion. Indeed, almost the whole geological history of the coast is revealed from the very earliest pre-Cambrian rocks exposed around St David’s to the sand dunes and shingle banks still in the process of creation today.

Stackpole Head (Walk 4)

For the most part undisturbed by large settlement, wildlife of one kind or another is an ever-present distraction. Wildflowers carpet the coastal fringe, and animals such as badgers, foxes and rabbits are commonplace. There are plenty of other small mammals too, while adders and lizards can occasionally be found sunning themselves on the rocks. These are food for the many predatory birds that patrol the cliffs; kestrels and buzzards hover and wheel in the sky, and the peregrine falcon is once again nesting at sites along the coast. Chough and raven are everywhere, as is the ubiquitous pigeon, but it is the seabirds that understandably command the greatest attention. In spring and early summer during the breeding and feeding season, inaccessible cliffs around the coast – as well as the offshore islands such as Ramsey, Skomer, Skokholm and Grassholm – attract countless birds. Umpteen species, both resident and visiting, can be seen, and include gannet, fulmar, Manx shearwater, storm petrel, shag, cormorant, kittiwake, tern, guillemot, puffin and, of course, the razorbill, which the national park has adopted as its emblem.

The cliffs are a superb vantage point for watching Atlantic grey seals, which appear at many places along Pembrokeshire’s coast throughout the year. They are most numerous during late spring and early autumn, when large numbers arrive to give birth to their pups. The rocky beaches of tiny isolated coves or the dark recesses of sea caves serve as nurseries, which echo to the melancholy cries of the white pups awaiting their mothers’ return. You might also see some of the coast’s less-common visitors such as porpoises or dolphins and, if you are really lucky, perhaps a minke or orca whale.

An unspoilt hinterland

Away from the coast the walking is equally fine and there is just as much to see. Bold in profile and totally unspoilt, the Preseli Hills impart a wonderful sense of remoteness. Yet they are easily reached and on a fine day offer relaxed walking that is hard to beat. The views extend from one end of Wales to the other, and the mountains of Ireland can be visible across the sea. Although lacking the rugged summits of Snowdonia or the English Lakeland hills, the tops are broken by enigmatic craggy outcrops, jumbled heaps of fractured rock that when half hidden by tendrils of swirling mist would not appear out of place in some alien planetary landscape. More mystery and conjecture is evoked by the numerous burial mounds, earthworks and cairns that litter the slopes, vestiges of civilisations that spanned 3000 years, from the time when the pyramids were built in Egypt until the Romans arrived in Britain in AD43.

Less well known – but equally fascinating – the tidal reaches of the Daugleddau have their own special magic. An abundance of birdlife is attracted by the rich mudflats exposed at low water, with many birds arriving to overwinter in the relative shelter of the estuary. Ancient oak woods cloak the valley slopes and harbour a lavish variety of flowers almost throughout the year. Largely deserted today, the woodland conceals clues to the industrial and social history of the settlements that sprang up along the river’s banks.

The waterway once teemed with barges and small boats, a trading route from the heart of the county to the open sea. But the area was busy in its own right too, for just below the surface are extensive coalfields that were exploited from as early as the 16th century. Many of the seams are of high-quality anthracite that was exported as far afield as Singapore, but although the industry persisted into the last century there is hardly any trace left today. Overgrown dells and abandoned trackways, or rotting piers backed by a handful of cottages are now almost the only visible evidence of a once thriving industry.

The Eastern Cleddau below Minwear Wood (Walk 26)

Above the tidal limit, Pembrokeshire’s rivers run fast and clear, often through narrow gorges where man’s only exploitation has been to manage the centuries-old woodland cloaking the steep slopes. With a wealth of native species such as birch, ash, holly, hazel and oak, their continuity has been preserved by coppicing, selective felling and natural regeneration. Relatively undisturbed by human activity and providing shelter and food, these are havens for all manner of wildlife. Blackbird, wren, chiffchaff, nuthatch, chaffinch, goldfinch, blue and great tits, and green and spotted woodpeckers are just some of the birds you might see. Squirrels and small rodents scurry about and foxes and badgers are fairly common, although you need to be there at dusk to catch sight of Mr Brock.

Ancient woodland is to be found elsewhere too, perhaps most notably in the north at Pentre Ifan and Ty Canol, areas noted for the ferns and lichens that grow in abundance among the hillside boulders and upon the trunks of the trees. Although rivers and streams are plentiful, there are no significant natural lakes in the county. However, since its opening in 1972, the Llys-y-frân Reservoir has established itself as a splendid substitute, attracting an ever growing diversity of wildlife as well as providing a fine recreational facility while also meeting the water supply needs of the area.

One of the great delights in wandering through Pembrokeshire is to savour its quiet, narrow lanes. The herbal splendour found along the cliff paths and in the woods is repeated here and the banks and hedges are packed with interest throughout the year. Bramble, gorse, heather, hazel, blackthorn and honeysuckle abound, and there is an almost continuous succession of flowers sprouting from the crevices and beneath the bushes. Violet, primrose, lesser celandine, bluebell, campion, wood anemone, herb robert, foxglove, tormentil, stitchwort and the ever-present parsleys; the list is almost endless.

Gorse covers the hillside above Pwllgwaelod (Walk 17)

Things to take along

Whether following the coast, wandering the hills or exploring the valleys and woods, the walking everywhere is superb and will invariably reveal something unexpected along the way. Unless you really are an expert it is a good idea to take along pocket flower and bird field guides, and a small pair of binoculars will prove invaluable, especially along the coast.

Getting there

Pembrokeshire is easily accessible by road and, in some cases, rail, with national services running to Tenby, Pembroke Dock, Milford Haven, Haverfordwest, Fishguard and Cardigan. The nearest airports serving the region are Cardiff, Birmingham and Liverpool, where you can hire a car. Accommodation (whether it be camping, bed & breakfast or hotels), restaurants, cafés and pubs throughout the region are generally welcoming and of a high standard, providing good value for money.

Getting around

Pembrokeshire’s roads are generally quiet and parking is rarely a problem, but where there is no formal car park, please ensure your vehicle is not causing an obstruction. All the main access points along the coast are served by excellent bus services, with other routes extending into the Preseli Hills and the Gwaun Valley. The walks described in this collection are all circular, but local transport offers the possibility of turning some of them into shorter one-way routes. Please use the buses where you can, as this will help sustain the case for further improvements and keep the lanes enjoyable for walkers, cyclists and horse riders. Timetables and information are available at local Tourist Information Centres and from the Greenways website (see the information section in Appendix B), but note that some routes operate a reduced service from October until the end of April.

Terrrain and weather

Nowhere is the walking overly demanding, but be aware that, particularly along some sections of the coast, paths can make successive steep climbs and descents, which can be tiring if you are unused to strenuous routes. The Pembrokeshire climate is generally mild, and even the middle of winter can produce delightful days when the shining sun warms the air. But snow does lie from time to time on the Preseli Hills, and mist and cloud can cause navigational difficulties there for the inexperienced. Wind and rain may occur at any time but, providing you are equipped with suitable weatherproof clothing, need not spoil your enjoyment. However, take care, especially along the cliffs, which are sometimes slippery underfoot and where unexpected gusts can force you off balance. Walking boots offer the best protection for your ankles on rough ground, and gaiters help to keep your feet dry. As with all country walking, paths may be muddy during and after wet weather, and lush summer vegetation often makes trousers more appropriate than shorts.

Tides

On some of the walks you need to be aware of how the tide will run during the course of the day. Beaches may have coves that are cut off as the tide rises, and if you venture down you need to keep an eye open as the water comes in. However, three walks exploring the upper reaches of the Daugleddau are affected too: from Cresswell Quay, Landshipping Quay and Little Milford Wood. Details of the sections affected are given within the appropriate chapters, and you can get information on tide times from local Tourist Information Centres or by consulting the national park’s free newspaper Coast to Coast.

A changing countryside

Inevitably, nothing is static; the line of a footpath may change, forest areas are felled and replanted, signs may alter and, even in the countryside, there can be development. Over the years rangers from both Pembrokeshire’s national park and County Council have performed sterling work in improving the network of paths and tracks; replacing stiles with gates, installing bridges, re-opening lost routes and tackling the never-ending cycle of vegetation control. However, should you encounter a problem, please help by reporting it to the relevant organisation. You will find contact details in Appendix B.

Using this guide

This collection of walks includes something for everyone, from novices to experienced ramblers. None of the walks demand technical skill and, in good weather, pose few navigational problems. However, when venturing onto the higher ground of the Preseli Hills, competence in the use of map and compass is important, particularly in poor weather. Pembrokeshire’s network of public footpaths and tracks is extensive and signposts and waymarks are generally well positioned to confirm the route.

However, on farm and moorland away from the coast, the line of the path on the ground might not always be obvious. It is therefore recommended that, in addition to the route description and map extracts within the book (taken from the Ordnance Survey 1:50,000 Landranger series), you also consult the relevant Ordnance Survey Explorer Outdoor Leisure map. These are produced at a scale of 1:25,000, and show the terrain in greater detail, including field boundaries.

Each walk is headed with key facts that provide essential information about the walk, including the distance and approximate time as well as details of useful facilities such as refreshments, toilets and parking. More general information about the area can be found in Appendix B.