Читать книгу The Yermakov Transfer - Derek Lambert, Derek Lambert - Страница 9

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

The kidnap plot was first conceived by Viktor Pavlov in Room 48 of the Leningrad City Court at Fontanka on December 24, 1970.

On that day two Jews were sentenced to death and nine to long terms of imprisonment for attempting to hi-jack a twelve-seater AN-2 aircraft at Priozersk airport and fly it to Sweden en route to Israel.

At the back of the courtroom, which seated 200, Pavlov listened contemptuously to the details of the botched-up scheme. When he heard the evidence of one of the accused, Mendel Bodnya, revulsion burned inside him like acid.

Bodnya told the court that he had yielded to hostile influence and deeply regretted his mistake. He thanked the authorities for opening his eyes: he had only wanted to go to Israel to see his mother.

Bodnya got the lightest sentence: four years of camps with intensified regime, with confiscation of property.

Pavlov’s contempt for the other amateurs was tempered by admiration for their brave, hopeless idealism.

The woman Silva Zalmanson in her final statement: “Even now I do not doubt for a minute that some time I shall go after all and that I will live in Israel.… This dream, illuminated by two-thousand years of hope, will never leave me.”

Anatoly Altman: “Today, on the day when my fate is being decided, I feel wonderful and very sad: it is my hope that peace will come to Israel. I send my greetings today, my land. Shalom Aleikhem! Peace unto you, Land of Israel.”

When the sentences were announced Pavlov joined the disciplined applause because he had cultivated the best cover there was – anti-Semitism. A woman relative of one of the defendants rounded on him: “Why applaud death?” He ignored her, controlling his emotion as he had controlled it so often before. He was a professional.

He watched impersonally as the relatives climbed on to the benches weeping and shouting. “Children, we shall be waiting for you in Israel. All the Jews are with you. The world is with you. Together we build our Jewish home. Am Yisroel khay.”

With tears trickling down his cheeks an old man began to sing “Shma Yisroel”. The other relatives joined in, then some of the prisoners.

Viktor Pavlov sang it too, silently, with distilled feeling, while he continued to applaud the sentences. Then the local Party secretary who had collected the obedient spectators realised that the hand-clapping had become part of the Zionist emotion. Guiltily, he snapped, “Cease applause.” Another amateur, Pavlov thought as he stopped clapping: each side had its share of them: the knowledge was encouraging.

At 11 a.m. on December 30, at the Moscow Supreme Court, after a sustained campaign of protest all over the world, the two death sentences were commuted to long sentences in strict regime camps and the sentences on three other defendants reduced.

While the Collegium of the Supreme Court was deliberating the appeals Pavlov waited outside noting the identity of a couple of demonstrators. With their permission he would later identify them to the K.G.B. at their Lubyanka headquarters opposite the toy store. They would be locked up for a couple of weeks for hooliganism and his cover would be strengthened.

The Jewish poet, Iosif Kerler, was giving interviews to foreign correspondents. The Leningrad verdict, he told them, was a sentence on every Jew trying to get an exit visa for Israel. But Pavlov knew there was no point in laying information against Kerler: the police had a dossier on him and there was nothing poetic about it. Nor was there any point in informing on the Jewess from Kiev who was telling correspondents about her son dying in Jerusalem: the K.G.B. had her number, too.

No, the information had to be new and comparatively harmless. Pavlov had an arrangement with a Jewish schoolteacher who didn’t mind a two-week stretch during the school holidays. He wore a piece of white cloth pinned to his lapel bearing in Hebrew the slogan NO TO DEATH with a yellow, six-pointed Star of David beneath it. He meant well but he was over-playing his hand; it was like laying information against a man walking across Red Square with a smoking bomb in his hand. A pretty Jewess had also agreed to serve a statutory two-week sentence. Pavlov would report that she had been chanting provocative Zionist slogans; although she had been doing nothing of the sort because, like Pavlov, she had little time for pleas and protests; Israel was strength and you didn’t seek entry with a whine. Pavlov stared at her across the crowd; she stared back without recognition; she, too, was a professional.

Among the correspondents Pavlov noticed the American Harry Bridges. Tall, languid, watchful. He had the air of a man who had the story sewn-up. He didn’t bother interviewing the demonstrators and managed to patronise the other journalists. Pavlov admired him for that; at the same time he hoped he would rot in hell.

When the success of the appeals was announced the demonstrators sang and shouted their relief. Viktor Pavlov felt no relief; now the amateurs had even lost their martyrdom. They had perpetrated an abortion: he was conceiving a birth.

* * *

Viktor Pavlov belonged to that most virulent strain of revolutionaries: those who don’t wholly belong to the cause they are fighting for. He was fighting for Soviet Jewry and he was only part Jewish.

Sometimes his motives scared him. Why, when so many full-blooded Jews advised “Caution, caution” did he, a mongrel, call for “Action, action”? What worried him most was the sincerity of his conviction. Was the scheming and inevitable brutality merely a heritage? – a family tree planted in violence? And the right of the Jews to emigrate to Israel: Was that merely a facile cause?

Passionately, Viktor Pavlov sought justification. He found it mostly in the richness of his Jewish strain of blood. So deeply did he feel it that it sometimes seemed to him that it had a different course to his gentile blood.

His great, great grandparents had been Jews born in the vast Pale of Settlement in European Russia where the Tsars confined the Jews. After the murder of Alexander II the Jews became scapegoats and Pavlov’s ancestors were exiled to Siberia to one of the mines which produced 3,600 pounds of gold loot a year for Alexander III.

The persecution of the Jews continued and Viktor Pavlov found deep, bitter satisfaction in its history. Scapegoats; they were always the scapegoats. In 1905 gangs like the Black Hundreds carried out hundreds of pogroms to distract attention from Russia’s defeat – its debacle – at the hands of the Japanese. Followed in 1911 by the Beilis Case when a Jew in Kiev was accused, and subsequently acquitted, of the ritualistic murder of a child.

By this time the Jewish blood that was to flow in Viktor Pavlov’s veins had been thinned. His grandmother, Katia, married a gentile, an ex-convict who helped to build the Great Siberian Railway and became a gold baron in the wild-east town of Irkutsk.

Here Pavlov’s soul-searching got waylaid. His great grandfather lived in a palace, brawling, whoring and gambling and using gold nuggets for ashtrays. He was a millionaire, a capitalist, and thus an enemy of the revolutionaries – a White Russian. Most of the Jews were Reds.

Pavlov allowed his great grandfather to retreat from his deliberations; across Eastern Siberia during the Civil War where he was finally shot by the American interventionists who were not always sure which Russians they were supporting – Reds or Whites.

Pavlov concentrated on World War I. Scapegoats again. The Tsarist government, trying to explain its shattering defeats by the Germans, blamed traitors in their midst. Jews, naturally.

Then, after the Revolution, the Jews came into their own. The Star of David in ascendancy; but too brilliantly, too hopefully, a shooting star doomed to expire. The Jews were among the leaders of the October Revolution and, with an optimism which had no historical foundation – bolstered by the Balfour Declaration in November, 1917 – they anticipated the end of persecution. They were Russians, they were Bolsheviks, they were Jews.

Even V. I. Lenin lent his support in a speech in March, 1919:

“Shame on accursed Tsarism which tortured and persecuted the Jews. Shame on those who foment hatred towards the Jews, who foment hatred towards other nations.

“Long live the fraternal trust and fighting alliance of the workers of all nations in the struggle to overthrow capital.”

Today, Viktor Pavlov thought, it was Leninism that he was fighting.

During the Civil War his grandfather, half-Jewish, a rabid Bolshevik, fell in love with a wild Jewish Muscovite who wore a red scarf and gold earrings. Illegitimately, they sired Pavlov’s father.

According to Pavlov’s father, Leonid, they had always intended to marry. But when the shooting star faded and Stalin, frightened of the Jewish power around him, began to turn on the Jews again with a ferocity unequalled by his aristocratic enemies, there came the 1 a.m. knock on the door. Pavlov’s grandfather, who looked a little like Trotsky, was away addressing a meeting of railway workers; but his wife was at home and they took her away to one of the camps which history has always provided for Jews and she died giving birth to Leonid Pavlov.

There is my motive, Viktor Pavlov thought. The origins of my hatred. More often than not, he believed it.

* * *

He was born in violence during the siege of Leningrad in World War II, the son of a teenager, Leonid Pavlov, and a peasant woman, possibly wholly Jewish, possibly not, who had found time in between dodging shells and eating stews made of potato peelings and dog meat, to make love and get married. She was killed by a German shell shortly after giving birth to Viktor.

So many records were destroyed during the siege that it was easy to register Viktor as a Russian. This grovelling hypocrisy angered him in his teens, but later it was to become his strength.

When he was ten Viktor Pavlov stopped some bullies beating up a small boy with springy black hair, rimless glasses and a dark complexion, in the school playground in Moscow.

“Why,” he demanded, grabbing the arm of the biggest bully, “are you picking on him?”

The bully, whose name was Ivanov, was astonished. “Why? Because he’s a Yid, of course.”

“So what?” Pavlov was an athletic boy with flints in his fists which commanded respect.

“So what? Where have you been? Everyone knows about the Jews – it’s in the papers. They’ve just closed the synagogue down the road. It was the centre of the black market in gold roubles and Israeli spies.”

“I didn’t know you read the papers,” Pavlov remarked. “I didn’t know you could read.”

A crowd had gathered round the two protagonists on the sunlit, asphalt playground. The original victim had vanished.

Ivanov, who had a pudding face and pale hair cut in a fringe, ignored the question. “My father’s told me about the Yids. He was in the war.…”

“So was mine.”

“He said the Jews wouldn’t fight. He says we should finish off the job Hitler started.”

“Then your father’s an idiot. I was born in Leningrad. The Jews fought well. And what about the Jewish generals?”

Dodging logic, Ivanov searched for a diversion. He stared closely at Pavlov’s intense dark features, his cap of black hair, his hawkish nose; he saw intelligence and good looks and it made him mad. “Are you a Yid?” he asked. “Are you Abrashka?”

The crowd of boys was silent. The question was a provocation, an insult; although they weren’t sure why. Why was an evrei, so different from a Kazakh, a Kirghiz, a Uzbek?

Ivanov grinned. “Prove it.”

A cold, dark anger froze inside Pavlov, like no anger he had experienced before. He wanted to batter Ivanov into insensibility; to kill him. “I’ll prove it” – he put up his fists – “with these.”

Ivanov was still trying to grin. “That’s not proof.”

“What proof do you want?”

“Show us your cock.”

Recently, there had been a scandal in the suburb about Levin the circumciser. He had performed the small operation on the penis of a baby and then gone to Leningrad for a couple of days. But there had been sepsis, so the baby’s parents took the baby to a clinic where a Jewish doctor dressed the cut and told the parents they needn’t worry. But a porter reported the case to the police.

Three weeks later, after intensive interrogation, Levin made a public address renouncing his profession. It was, he announced in a beaten voice, a barbaric ritual. He appealed to Jews all over the Soviet Union to abandon it.

Pavlov advanced on Ivanov. Ivanov backed away appealing to the others: “I bet he’s been cut.” A few sniggered, the rest remained silent because there was ugliness here they couldn’t comprehend.

Pavlov hit him first with his left, then with his right, dislodging a tooth. Ivanov fought back strongly but he couldn’t match the inexorable determination of his opponent, his controlled ferocity. He got home blows in the face and stomach but they had no visible effect on Pavlov who kept coming at him. Pavlov bloodied Ivanov’s nose, closed one eye, buckled him with a punch in the solar plexus. Ivanov went down and stayed down whimpering.

Pavlov stood over him. “So you want to see my cock? Then you shall see it and lie there while I piss all over you.”

Pavlov unbuttoned his fly and took out his penis, foreskin intact. But he was saved from degrading himself by the appearance of a teacher. He buttoned himself up, standing defiantly beside his fallen opponent.

They were both punished for fighting but no reference was made to the reason for the fight. The teacher seemed to understand Ivanov’s attitude; likewise he understood Pavlov’s reaction to the suggestion that he might be a Jew.

This was Pavlov’s private shame: that he had taken the suggestion as an insult. He resolved to find out more about his mongrel heritage and asked his father: “Am I a Russian or a Jew?”

They were sitting in the small wooden house in the eastern suburbs of Moscow drinking borsch soup, mauve and curdled with dollops of cream, and black bread, which Viktor rolled into pellets. His father, although still a young man, was almost a recluse, hiding his Jewishness, earning a meagre living doing odd jobs and keeping his nose clean. Although in his death throes, Stalin was still on the ram-page.

His father stopped drinking his soup. “Why do you ask?”

Viktor told him what had happened in the playground.

His father looked worried. “Why fight about a thing like that?”

“I don’t know. Why should I be so angry because he suggested I was a Jew?”

His father leaned across the table, prodding the air with his spoon. “Listen, boy, you are a Soviet citizen. You are registered as one. I am a Soviet citizen, too. Forget anything you may know about your ancestors.” He paused. “About your mother even. This is a great country, perhaps the most powerful country in the world. Be proud to belong to it. Don’t sacrifice your life for the sake of the martyrs.”

Looking at his father’s wasted features, Viktor knew that, although he spoke truths, he lied. Subsequently he wondered if the decision to fight for Zionism was made then. Out of perversity, out of contempt – not fully realised at the time – for paternal weakness; out of his own shame.

From the boy he had protected in the playground he learned about Israel. It was once called Palestine and it was populated by people who had come from Egypt thousands of years ago. They read the Bible, worshipped their own God, their land was destroyed by the Romans and they spread all over the world. With them they took their traditions, their Bible, their customs, their diets, their suffering. Throughout history, the boy told his saviour, the Jews had been persecuted and in the holocaust they had been slaughtered by the million by the Nazis.

Viktor envied the boy his birthright; but he couldn’t understand his acceptance of his plight.

Pavlov’s Jewishness continued to bother him in his early teens; but it was still only a needle, not the knife it was to become. There were summer camps and sports and girls to distract him; he was emerging as a scholar with a keen mathematical brain and the school had high hopes for him at university.

It wasn’t till he reached the age when young men seek a cause – when, that is, he became a student – that Viktor Pavlov took the first steps that were to lead him on the path to high treason in the year 1973.

* * *

He was nineteen and sleeping with a passionate Jewish girl, a little older than himself, in the Black Sea resort of Sochi. He was at a Komsomol summer camp, she was staying in one of the town’s 650 sanatoriums. Her passion and expertise gave him much pleasure; but her fervour had a long-term quality to it and he expected trouble if he broke up the affair, from her brother, a wiry young man with a lot of muscle adhering to his prominent bones, the face of a fanatic and a premature bald patch which looked like a skull-cap.

One sleepy afternoon, with the sun throwing shoals of light on to the blue sea, Viktor and the girl, Olga Soliman, walked up the mountain road to Dagomys, the capital of Russian tea, 20 kilometres from Sochi. They drank tea on the porch of a log cabin, ate Kuban pies, then headed for the woods. Their love-making had a heightened lust to it on a bed of pine-needles with the sun casting leopard-spots of warmth on their bodies. Such was the aphrodisiac quality of the open air, the sun, the pinewoods, that Viktor was quicker than usual. But, anticipating him, so was Olga.

She pointed at his sex shrinking inside its little fleshy hood. “I shouldn’t let you touch me with that,” she said. “Why don’t you have it cut off?”

It was a joke and Viktor laughed. But it was also the truth and a part of him hated the joke.

“Too late now,” he said. “Perhaps I should have the whole thing cut off.”

She nuzzled him, biting his ear. Her skirt was around her waist and her big, brown-nippled breasts were still free. She said: “Don’t ever do that. I’ve got a lot of use for that.” In the long years to come, she implied. And yet, Pavlov thought, with the sun dappling his skin, and the smell of her in his nostrils, I love her. Knowing at the same time that he didn’t, not in the absolute, permanent sense. Love was an emotion he could control. He wasn’t so sure about hate.

Arm in arm, they walked down the mountain road to Sochi where, it was claimed, the mineral waters of Matsesta could help patients suffering from heart diseases, neuroses, hypertension, skin diseases and gynaecological disorders. There wasn’t much that Sochi couldn’t alleviate and the brochures asserted that 95 per cent of all those seeking treatment left the resort considerably improved or cured. But Viktor Pavlov wasn’t among them. His disease went back centuries and no one had ever touched upon a cure.

When they arrived at the Kavkazskaya Riviera sanatorium which took Intourist guests and was therefore prestigious, Olga’s brother, Lev, was waiting for them.

He looked at Viktor with fraternal menace. “Had a good time?” Olga’s parents were also staying at the sanatorium and the view was that Viktor Pavlov was already one of the family and should make it legal.

“Pleasant,” Olga said. “But exhausting.” Allowing the implication to sink home before adding: “It was a long walk.” She smiled contentedly – possessively, Viktor Pavlov thought.

They were standing in the lobby of the sanatorium, breathing cool, remedial air.

Lev said: “I have bad news for you.” He held a long mantilla envelope with the words Moscow University on it.

Olga took the envelope. “Why bad news?”

Lev Soliman grimaced. “Is it ever any other?”

They were all three at the University studying different subjects.

“You’re a pessimist,” Olga told her brother.

“I am a realist.”

“To hell with your realism.”

But her fingers shook as she ripped open the envelope with one decadent, pink-varnished fingernail.

She read the letter slowly. Then she began to shiver.

“What is it?” Viktor asked.

“What’s the good news?” her brother asked.

She re-folded the letter, replacing it in the envelope. “I’ve been expelled from the university,” she said.

They were silent for a moment. Then Viktor demanded: “Why?” He paused because he knew the answer. “You were doing well … your examination marks were good.”

Lev Soliman turned on him. “Don’t pretend you don’t know. Don’t be too much of a hypocrite, a half-caste. She has been expelled because she is a Jew.”

* * *

When they returned to Moscow, Viktor Pavlov told Lev Soliman that he thought he should quit university.

They were walking through Gorky Park, filled this late-summer day, with guitar-strumming youths, picknicking families, lovers, union soldiers and sailors. Bands played, rowing boats patrolled the mossy waters of the lake, the ferris wheel took shrieking girls to heaven and back again.

“Why?” Lev asked. “Your guilt again?”

“Perhaps.” They stopped at a stall near a small theatre and bought glasses of fizzy cherry cordial. They were close now, these two, close enough to exchange insults without malice. “I feel like a traitor.”

“Don’t,” Lev Soliman said. “Feel like a hero.”

“What the hell are you talking about?”

“I’ll tell you.” Lev pointed at the ferris wheel. “Let’s take a ride. No one can overhear us up there. Not even the K.G.B.”

The wheel stopped when they were at its zenith and they looked down on Moscow glazed with heat; the gold cupolas of discarded religions, the drowsy river, the fingers of new apartment blocks. Lev Soliman pointed down at the pygmy people in the park. “Good people,” he said. “A great country. Make no mistake about that.”

“I don’t,” Viktor told him. “I was born in Leningrad. Any country that can come back after losing twenty million is a great country. But not so great if you’re a Jew, eh?”

“But you’re not.”

A breeze sighed in the wheel’s struts; the car perched in space, swayed slightly.

Pavlov said: “I am a Jew.”

“That’s not what it says on your papers.”

“You can’t blame me for that. There are thousands of Jews registered as Soviet citizens through mixed marriages.”

Lev shrugged. “Maybe. But you’re a more convincing case. All your family records destroyed in Leningrad. Perhaps your mother was pure Russian.”

“She was a Jewess.”

“That’s not what your father told the authorities. And he’s registered as a Soviet citizen, too. So you see, your case is pretty clear-cut.”

Viktor twisted round angrily, making the car lurch. “What are you getting at?”

“Simply this.” Instinctively Lev looked around for eavesdroppers; but there were only the birds. “You can be far more useful to the movement than anyone with Jew stamped on his passport.” He gripped Viktor’s arm. “There is a movement within the movement. That’s where you belong.”

* * *

One month later Lev Soliman was expelled from the University. His one-room apartment was searched under Article 64 – “betrayal of the Motherland”. He was taken to the Big House and interrogated. A fortnight later he was transferred to a mental institution. Viktor saw him once more two years later; by that time he was insane.

* * *

Lev Soliman left Viktor Pavlov with the embryo of an underground movement that had its origins in April, 1942, when the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee of the Soviet Union (JAC) was founded. In those days the Russians needed the Jews to help fight the Nazis and to spread propaganda to the four corners of the world to which the Diaspora had taken them.

For the first time since the Jewish sections of the Communist Party, the Yevsektsia, were disbanded in 1930, Soviet Jewry had in JAC an officially-sanctioned organisation. Its journal was called Unity and Lev Soliman’s parents were among its contributors.

JAC was, of course, another shooting star spluttering in the darkness of prejudice. The Jews thought that, by co-operating with the Soviets in defeating Hitler, they were also constructing a peaceful future in Russia. In 1943, when JAC emissaries Mikhoels and Feffer went on a tour of Jewish communities in the U.S.A., Britain, Canada and Mexico, Joseph Stalin personally wished them well.

Such was the hope of a new understanding between Russians and Jews that Zionist leaders even suggested a meeting between Chaim Weizmann and Stalin. Churchill was asked to get them together at Yalta in 1945; but Churchill turned down the idea: Churchill knew better.

All this time the Solimans worked joyously for the cause and the future of their son, Lev.

The Allies finally beat the Nazis and the Soviet attitude towards JAC began to cool: the Black Years of Stalin’s Jewish purges were beginning. On January 13, 1948, Solomon Mikhoels, director of the Moscow Yiddish State Theatre and one of the two emissaries who had spread the word to the world in 1943, was murdered in Minsk. He was a personality and he was emerging as the leader of Russian Jewry.

The murder was followed by the liquidation of the Committee. Lev Soliman’s parents were charged under Articles 58/10, part 2, to ten years in strict regime camps on charges of “belonging to a Jewish nationalist organisation and spreading nationalist propaganda”. Lev was looked after by the state.

When Kruschev came to power the Solimans were pardoned and the family was reunited in Moscow. Lev continued his education, winning a place at Moscow University.

But JAC had left its scars on him. He despised naïveté, he trusted no one. Organised protest served a function, but to Lev, it had a whine about it, a recognition of Soviet supremacy. Caution, caution. Lev Soliman spat on caution.

He gathered around him half a dozen young fanatics who believed that violence was the only honourable solution. Like other extremists throughout the world they didn’t necessarily represent the beliefs of those they fought for. But this didn’t bother them; they regarded the patient resolve of Soviet Zionists as weakness and they operated clandestinely treating both orthodox Zionists and Russians as the enemy.

This was the nucleus of subversion to which Lev Soliman introduced Viktor Pavlov. The nucleus of which Pavlov was soon to become leader.

* * *

In the autumn of 1962 Pavlov began to construct his cover. He already possessed Soviet nationality but he had to establish impeccable references. The secret police knew about his father; therefore they knew there was at least a strain of Jewish blood in him. So, with the approval of the K.G.B., he worked with the Jewish underground movement publishing samizdat newspapers, smuggling subversive literature out of the country – and informing on his colleagues.

Within a year he was an established agent provocateur in the student movement. He won a brilliant degree in mathematics and went to Leningrad to study computers to make himself invaluable to a country backward in such refinements.

There he met a girl who, at the age of eighteen, had been made a Heroine of the Soviet Union. Viktor Pavlov welcomed her as the means to make his cover unassailable.

Anna Petrovna was the spirit of Russia, the rose of Siberia. Her bravery was the inspiration for a legion of Komsomols to head east, to built cities in the frost, to tap the hostile territories of their wealth.

As a student geologist, Anna Petrovna had flown to Arctic Siberia in an eight-seater AN-2 with two young men. To her, the snow-covered taiga of the north, inhabited by reindeer and primitive tribesmen was a storehouse of precious stones – emeralds, amethysts, topaz, jasper, sapphires, garnets. But it was diamonds that fascinated her.

With a magnifying glass in one hand, she crawled beside a frozen river for two months, averaging a mile a day, searching for kimberlite, the blue-grey earth that advertises the presence of diamonds.

After the first month she couldn’t stand up straight. Towards the end of the second, when the wilderness was briefly thawing and she was paddling on raw knees in slush, she was on the point of giving up. One day she reached a spine of hills and gazed down on a plain patched with snow beneath a mauve haze. Idly, she stooped and picked up a handful of mud, straightening up painfully. The mud was blue-grey.

For a week she and the two young men dug. One bright morning they gazed down the shaft and saw a shiny blue light at the bottom. It was the first diamond chimney in the area and they called it “Blue Flash”.

Anna Petrovna and Viktor Pavlov met one evening at the White Nights club in Leningrad and fell in love; she unreservedly, he deeply and passionately but with a sliver of calculation in his soul, the chip of ice that never melted.

The marriage was popular. Such a fusion of talent; such a union of Russian beauty – he with his strong brown face and cap of glossy black hair, she the Siberian with her cool, glittering good looks – the sort of face that beckons from Aeroflot brochures. The wedding was honoured with a photograph in Komsomolskaya Pravda and a story that speculated on the handsome geniuses the couple would produce.

* * *

They spent their honeymoon in Siberia beside Lake Baikal – the Holy Sea, the Northern Sea, the Rich Sea. So right for their union with all its bizarre superlatives. Here Genghis Khan once camped in the heart of the territory of Marco Polo, Strogonoff, Yermak, Godunov, Kuchum. The deepest lake in the world, 400 miles long and 50 miles wide in places, filled by 336 rivers and emptied by only one, the Angara. Populated by fresh-water seals, omul and bright green sponges with which peasants clean their pots. Covered in winter by nine-foot deep ice which splits with a crack like thunder, tormented by storms and earthquakes which once, long ago, broke up the Gypsy Steppe on the eastern shore killing 1,300 people in the fissures, geysers and flood waters.

But today the waters were becalmed with floating islands of blossom like reflections of clouds and the only awesome sight was a ruff of white mountains in the distance.

They gazed upon it all from a rumpled bed in a guest house at Listvyanka. He very dark and hirsute beside her white body.

“Viktor Pavlov,” she said, “I love you. I’ll always love you.

“And I love you, Anna Petrovna, Heroine of the Soviet Union.”

“Does that bother you?” She stroked his chest, his flat belly, his sex.

“No, why should it?”

“It’s bothered other men.…”

“To hell with other men.”

“It upset them that I was made a heroine. That I crawled on my hands and knees for two months like some crazy cleaning woman.”

“It doesn’t bother me. They must have been very weak men.”

“They were. Stupid men. You’re the strongest man I’ve ever known. I felt your strength the first time we met.” She kissed him. “Like some inner force. Like a secret.”

“We all have secrets,” he said. “You do – your lovers, your deepest thoughts. Even what you’re thinking when you look out there.” He pointed at a bed of pink blossom drifting past the window. “We even keep secrets from ourselves.”

She shook her head so that her soft fair hair fell across her face. “I haven’t any secrets. Just the silly ambitions of any girl. A few meaningless men before the right one, the only one.” She pressed herself against him. “What’s your secret, Viktor Pavlov?”

He didn’t answer.

She held his arms down on the bed, staring at him with her blue eyes in which he could see sunlight and snow. “You frightened me a little.”

“I can’t imagine you being frightened of anyone.”

“Promise me you’ll always be faithful?” She thought about it. “Even when you go with other women – you’ll be faithful?”

“I’ll always be faithful,” he lied.

“And there will be other women?”

“No other women,” he told her, because that wasn’t the nature of his infidelity. I shall betray everything you cherish, he thought. He pressed his face against her firm white breasts.

“I’m glad,” she said, stroking his hair. “I was trying to be sophisticated. Men going with women and staying faithful to their wives. I wouldn’t like that.”

“Only you,” he said.

“We’ll go well together, you and I. We love the same things.”

“Ah yes,” he said. “The same things.” Thinking that in a way it was true.

“Viktor?”

“Yes?”

“I’m right, aren’t I?”

He kissed her, fondling her breasts, and, when he was hard again, made love with desperation.

When they were finished he glanced out of the window and saw a fishing boat drifting by, a breeze catching its sail. There was an illusory permanency about that moment and he always remembered it.

* * *

From 1962–67 Viktor Pavlov consolidated his position. He worked hard and became Russia’s leading authority on computers. He was given an apartment on Kutuzovsky Prospect in Moscow fit for a hero and heroine.

Before they left Leningrad he found, hidden in a bookshop opposite the Gostiny Dvor, a slim booklet printed by the old Yiddish publishers, Der Emes, containing the Hebrew alphabet. He kept it locked in his desk; later he obtained a Hebrew textbook.

But it was a period of frustration. There were now twelve members of his group of revolutionaries calling themselves the Zealots. But, short of planting bombs and reviving the rabid-Semitism of the Black Years, they found nothing positive to do. Pavlov raged inwardly. Caution, caution! His marriage suffered and Anna, not understanding, not knowing that he was a Jew, found consolation in her work taking her to the jewelled wastes of Siberia.

It wasn’t until 1967 when, in six days, the Israelis routed the Arabs, and the desire to settle in the Promised Land flamed across the Soviet Union, that the ultimate plan began to take shape in the minds of Viktor Pavlov and the Zealots.

* * *

The Jews were on the rampage bombarding authority with appeals. The Presidium of the U.S.S.R. Supreme Soviet, the Secretary-General of the United Nations, the International Red Cross, the Knesset, the Commission on Human Rights, UNO, premiers, editors, enemies, friends.

Viktor Pavlov who had studied the fluctuating history of Zionism in Russia regarded their efforts with good-natured cynicism.

The movement pre-dated world Zionism. In 1884, fourteen Jews from Kharkov landed in Jaffa and, even before World War I, most of the forty settlements in Palestine were founded by Russian Jewry.

When the Bolsheviks came to power in October, 1917, the movement seethed with excitement. But, as always, the excitement was short-lived. On September 1, 1919, the Cheka occupied the offices of the Zionist Central Committee in Leningrad, confiscated all documents and 120,000 roubles, arrested Committee members and banned the Chronicle of Jewish Life. Next day Zionist leaders were arrested in Moscow.

The harassment subsequently took a zig-zag course. Imprisoned Jews were released; others were arrested; seventy-five delegates to a convention in Moscow were accused of counter-revolutionary activities – peroxylin slabs of guncotton were said to have been found in the Zionist Central Committee offices – and thrown into Butirki jail.

In 1921 the pressure eased. In 1922 it stiffened again. Fifty-one members of the popular wing of the Zionists were arrested and accused of seeking help from reactionary elements ranging from Lloyd-George to the Pope.

Arrests continued on a vast scale. The Russians wanted to get rid of a few expendable trouble-makers and, in return for statements that their activities were anti-Soviet, some were allowed to go to Palestine.

By 1928 thousands of Jews were in prisons and camps. They were beaten, tortured, starved, thrown into solitary confinement. By 1929 all the Hechalutz collective farms preparing Jews for conditions in Palestine had been liquidated. Between 1925–26, 21,157 Jews managed to get out of Russia: between 1931–36, only 1,848 made it to Palestine.

In 1934 the last outpost of underground Zionism, the Moscow Central Executive Committee of Tzeirei Zion and the Union of Zionist Youth, was destroyed. Its members were jailed and the Government presumed Zionism dead.

It was reincarnated at the beginning of World War II when the Soviet Union annexed tracts of Eastern Europe, increasing its population by two million Jews, predominantly Zionist. Hundreds of thousands of them were promptly sent to forced labour camps.

In June, 1941, the Germans invaded Russia, slaughtering any Jews they encountered, and, years later, the Russians built a playground over the site of one of their massacres at Babi Yar.

Then came the formation of JAC. Hope followed inevitably by disillusion.

After the war Stalin supported the creation of the State of Israel because he thought it heralded the break-up of British power in the Middle East; Russia was one of the first powers to recognise the new country in 1948. But, after Stalin’s death in 1953, the policy changed: the Americans held the influence in Israel and the Soviet Union decided to undermine Western power by supporting the Arabs.

Inside Russia, Krushchev turned on the dead dictator Stalin, denouncing his butchery. Viktor Pavlov remembered the impact of the Khrushchev speech in his schoolroom. He also remembered that it made no mention of Stalin’s persecution of the Jews.

During Krushchev’s reign the terror inside the Soviet Union relaxed. When he was deposed and Leonid Brezhnev and Alexei Kosygin finally came to power, Premier Kosygin announced in Paris on December 3, 1966, that “as far as the reunification of families is concerned, if some families wish to meet or if they want to leave the Soviet Union, the road is open to them and there is no problem in this.…” On December 5 his statement was published in Izvestia.

It launched a flood of applications for exit visas to the OVIR.

Between June 5–11, 1967, Israel smashed the Russian-equipped armies of Egypt, Syria and Jordan and on June 10 the Soviet Union broke diplomatic relations with Israel; the Soviet attitude to Jewish emigration hardened once more.

On August 5 Viktor Pavlov chanced upon a copy of Sovietskaya Latvia in which Zionism was likened to the Mafia. He liked the comparison.

* * *

The plot assembled in several phases. In 1967 it was merely concerned with getting the Jews out of Russia. At a party in 1969, one year before the Leningrad skyjack trial, it assumed a more definite shape.

The party was at Pavlov’s Moscow apartment on Kutuzovsky in the complex of blocks where foreign diplomats and journalists lived, guarded at the gates by militiamen and bugged by the K.G.B. Many residents regarded the hidden microphones as a joke; about two committed suicide every year. The Pavlov’s got the apartment because the complex was one of the best in town and it was salutory for foreigners to see the pride of Soviet man and womanhood crossing the shabby courtyard.

The Pavlovs’ guests that evening included scientists, mathematicians, geologists, Yevtushenko the poet, a ballerina from the Bolshoi and some of the staff of the prestige magazine Novy Mir.

Pavlov was talking to Professor David Gopnik, associate member, Ukranian Academy of Sciences, department chief, Donetsk Computing Centre. They talked in symbols and electrical pulses, boring other guests so that finally they were isolated in a corner of the lounge.

Gopnik, a thin, bespectacled man with a low forehead contradicting popular beliefs about intelligence, said casually: “I tried to get out again today.”

Pavlov looked at him with surprise. “Get out of where?”

Gopnik looked equally surprised. “Out of Russia, of course. They turned me down again.”

“I didn’t realise you were a Jew.”

Gopnik grinned. “Feed me back through a computer and you’d end up with Moses.” He glanced around the other guests, voluble with Soviet champagne and Stolichnya vodka bought at the dollar shop on the first floor of the block. “And I’m not the only one here. A few of your guests are the product of mixed marriages. One or two have changed their names. Comrade Goldstein doesn’t get very far in Soviet society.”

“You’ve done all right,” Pavlov commented.

“Only because they need my brains.” Gopnik took a sliver of toast smeared with caviar and a glass of champagne from a tray carried by Pavlov’s hired waitress. “My brains are my misfortune. Without them I might be in Jerusalem today.” He stared at Pavlov knowingly. “Is there, by any chance, any Jewish blood in you, Comrade Pavlov?”

Pavlov hadn’t been asked the direct question since his student days. To deny it was treachery, blasphemy; like betraying your mother to the secret police. To confirm it was sticking a knife in the cover he had prepared for seven years. The K.G.B. knew of the diluted Jewish strain through his father, nothing more. As far as they were concerned he had proved himself an exemplary Soviet citizen willing to rat on any Zionist.

Pavlov said: “Would you like to see my passport?”

Gopnik said: “That won’t be necessary.” He licked some black spawn from his fingers. “It was very brave of you to invite a Jew to such a distinguished gathering.” He signalled to the waitress to bring him more champagne. “But, of course, you and your wife are somewhat privileged. And, of course, you didn’t know I was a Jew.”

His voice was loud with alcohol; Pavlov glanced around the lounge, with its contemporary furniture, its glassware from Czechoslovakia, its new TV set, to see if anyone was listening. “Perhaps we could meet tomorrow?” he suggested.

“Why? So that you can tell me the truth without fear of being overheard?”

Which was precisely what Pavlov had in mind. “Just to have a chat,” he said, listening to his own duplicity.

“What is there to talk about?”

“Perhaps I can help you.”

“And perhaps you can put the K.G.B. on to me.”

Pavlov spoke quietly and intensely wanting to grip the man by his lapels. “The K.G.B. already know everything about you. They’ve interrogated you, haven’t they?”

Gopnik shrugged. “Perhaps you might like to tell them that I’ve been spreading seditious propaganda.”

“Listen,” Pavlov said. “Meet me tomorrow. I promise I’ll tell no one.”

“The promise,” Gopnik asked, “of a Russian or a Jew?”

“A promise,” Pavlov said.

Gopnik looked at him uncertainly, swaying slightly. “Where?”

Pavlov smiled at last. “Outside Lenin’s tomb. Where else?”

Anna came across and took Viktor’s arm. She looked pale and elegant in a black cocktail dress bought in London during a geological conference. “Come and join the party,” she said. “Enough computerised conversation.” To Viktor she whispered: “You are being very rude, darling.” She led him away to a group of scientists and Pavlov wondered if any of them were Jews in disguise.

* * *

This phase of the plan, inspired unknowingly by David Gopnik, developed brilliantly during the evening and Pavlov became so elated that he hardly heard what anyone was saying. The guests put it down to vodka which was probably a contributory factor.

“Don’t you think you’ve had enough,” his wife whispered as he tossed back a glass of firewater. “You’re getting very flushed.”

In reply he took another glass from the tray. Anna stalked angrily across the room to join Yevtushenko’s audience.

Pavlov’s first thought was: If I could get the top Jewish brains to emigrate it would hit the Russians hard.

He oiled the thought with more vodka.

Then he thought: Why generalise? Why not deprive the Soviet Union of the nucleus of one branch of science?

He was talking to an assistant editor of Novy Mir who, with a Molotov cocktail of champagne and vodka under his belt, was giving his personal opinion of the literary merits of Daniel and Synyavsky. “Just my opinion,” the editor said, looking furtively around. “Just between you and me. Understand?” He prodded Pavlov in the ribs.

“Of course,” Pavlov said conspiratorially. “I understand.”

Supposing I could get all the Jewish nuclear physicists to emigrate?

Adrenalin and vodka raced in his veins.

“… and that’s my opinion of Pasternak.” The Novy Mir editor said challengingly.

Pavlov said: “I agree.” With what? “I’ve been to his grave. No one looks after it. Did you know that?”

The editor looked bewildered. “Fancy that,” he said.

What if I persuaded a team of Jewish nuclear physicists capable of making a hydrogen bomb to emigrate?

“Solzhenitzyn,” the editor whispered. “A great writer.”

Pavlov countered with: “What about Kuznetsov?”

But, of course, the Soviets would never grant nuclear physicists exit visas. The idea was crazy. Unless.…

The editor was still deliberating over Kuznetsov. His brain worked laboriously and his tongue was thick in his mouth. “Ah,” he managed, “Kuznetsov, a fine writer but …”

Unless I found a way to force their hand.

His mind raced with the possibilities; but it got nowhere, not that night.

The Novy Mir editor abandoned the enigma Kuznetsov. The flushed guests began to leave.

Tomorrow, Pavlov thought as he shook their hands automatically, I must reaffirm my faith with David Gopnik.

* * *

His wife was lying in bed waiting for him. She wore a pink cotton nightdress. She looked warm and sleepy and unheroic.

“Viktor,” she said, as he undressed clumsily, “you were very bad tonight.”

“I know.”

“I’ve never seen you drunk before.”

He fumbled with his shoelaces, sitting on the edge of the bed. “It doesn’t often happen.”

“Why tonight? Was there a reason?”

“Not particularly. It doesn’t matter. Everyone else was drunk.”

He was naked, searching for his pyjamas. “They’re under the pillow,” she told him. He climbed into bed, his legs heavy, and gazed at the spinning ceiling.

“Who was that man you were talking to?”

“Which man?”

“The man you were stuck with in the corner for nearly an hour.”

“His name’s Gopnik. He’s one of the best men on computers in the Soviet Union.” He closed his eyes but even the darkness lurched.

“Is he Jewish?”

He opened his eyes. “What if he is?”

She looked surprised. “Nothing. I just wondered if he was.”

He knew the drink was talking and he knew he must stop it. “You made it sound as if he was a leper.”

She was bewildered. “I didn’t mean to. I’ve nothing against the Jews. I just don’t understand why they want to leave Russia.”

The answers struggled to escape, but he fought them. He said: “Because they believe they have a land of their own.”

“But they’re more Russian than they’re Jewish.”

He wanted to shout “I’m a Jew” and see the shock on her face. “Not now,” he managed. “I’m too tired. Too drunk.” He reached for her. “Turn the other way. The smell of vodka must be foul.”

Obediently, she turned and he slipped his arms around her. She felt warm and soft, still smelling faintly of perfume. He cupped one breast in his hand. We’re good together, he thought. And yet I have to destroy our happiness.

“Viktor,” she said, “I’m frightened.”

But he was asleep.

* * *

The sky was pale blue this October morning with the sunlight finding the gold cupolas of the Kremlin and the sapphires in the frost on the cobblestones of Red Square.

The eternal queue was shuffling into the tomb, made of slabs of polished dark-red porphyry and black granite, to pay homage to Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, the man who gave them what they had.

Gopnik was waiting beside the queue wearing a shabby overcoat and a woollen scarf. He looked very vulnerable, Pavlov thought.

He greeted Pavlov almost shyly. “I believe I was rude last night. I’m sorry – I’m not used to alcohol. As you know we don’t drink too much.”

Pavlov patted him on the shoulder. “That’s all right. You had just had a disappointment.”

They walked beside the Kremlin walls, which enclosed so much beauty and so much intrigue, until they reached the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Alexander Gardens. The eternal flame was pale in the cold sunshine.

Gopnik pointed at it. “I, too, fought.”

“For what?”

“I sometimes wonder,” Gopnik said.

They drove in Pavlov’s black Volga to the Exhibition of Economic Achievements. A vast park with 370 buildings, models of sputniks and space ships, industrial exhibits, shops and cafés. A few brown and yellow leaves still hung on the branches of the trees.

They toured the radio-electronics building first to give credence to their visit. Then they sat on a bench with dead leaves stirring at their feet.

Pavlov said: “You know why I wanted to see you?”

“To tell me you’re a Jew. You didn’t have to.” Gopnik paused to light a cigarette. “Don’t take any notice of what I said last night. You have more sense than me.”

“Not necessarily. But I have my reasons. But I couldn’t allow you to leave Moscow thinking I was a hypocrite.” He smiled faintly. “A Judas.” He dug his hands into the pockets of his grey Crombie. He was conscious of his clothes, the deep shine to his black shoes, the elegant cut of his trousers. He asked: “How long have you been trying to get out of Russia for?”

Gopnik opened a cardboard case and consulted several sheets of paper headed Ukranian Academy of Science. “Like most people,” he said. “Since June, 1967.”

“How many times have you tried?”

“Twenty.” Gopnik ran his finger down the list. “The Director of the Department of Internal Affairs … The Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the U.S.S.R. … the Prosecutor General of the U.S.S.R. … the Chairman of the Commission of Legal Provisions of the Council of Nationalities, Comrade Nishanov … the editor of Literaturnaya Gazata, Comrade Chakovsky.…”

He paused for breath. “You see, I’ve tried.”

“Yes,” Pavlov said, “you’ve tried.”

“My story is the same as that of any Jew with brains. You can see the Russians’ point – ‘Why give your brains to the enemy?’ “

“Why do you want to go?” Pavlov asked.

“Why? You ask why?”

“Russia’s a good country if you accept their laws, if you live as a Russian. There’s not much anti-semitism these days, only anti-Zionism. Jews are getting places at universities if they toe the line like everyone else.”

“Perhaps,” Gopnik said thoughtfully, “you’re not a Jew at all. If you were you’d understand. The persecutions of the past, the attitudes of the present – they all count. But they’re not the end-all of it. I want to go to Israel because it is my land.” He paused. “Because it is written.”

Pavlov stood up. “Then you shall go.” He began to walk towards the car scuffing the leaves with his bright toe-caps. Unconsciously, he was taking long strides, hands dug in the pockets of his coat.

Gopnik hurried beside him, scarf trailing. “What do you mean?” His voice was agitated. “I don’t want any trouble. None of us want trouble.”

Pavlov walked quicker as if deliberately trying to distress Gopnik. He spoke angrily. “You don’t want trouble? What the hell do you expect to achieve without trouble? The Jews didn’t want trouble in Germany.…”

Gopnik panted along beside him. “You don’t understand. If we cause trouble we’re lost. The pogroms would start again. Back to the Black Years. The way things are we’re winning. More and more Jews are being allowed to leave. Soon, perhaps, we’ll all go.”

“All three million?”

“They don’t all want to go. But the policy’s changing. We’re winning.…”

“Grovelling,” Pavlov snapped. “Forced to crawl for a character reference from your employer, permission from your parents – or even your divorced wife, suddenly given fourteen days to get out which is never long enough, body-searched before you leave, paying the Government thousands of roubles blackmail money. Is that victory?”

“It’s suffering,” Gopnik said. “It’s victory.”

They passed some boys playing football, a couple of lovers arm in arm. A jet chalked a white line across the blue sky above the soaring Cosmonauts Obelisk. There didn’t seem to be much oppression around this glittering day.

They reached the car. A militiaman in his blue winter overcoat was standing beside it. He pointed at the bodywork. “One rouble fine, please,” he said. “A very dirty car.”

Pavlov let out the clutch savagely and headed back towards the Kremlin. “I’ll get you out,” he said. “Don’t worry – I’ll get you to Israel.”

Gopnik said: “Please leave me alone. Let me find my own destiny.”

“By crawling?”

“Don’t you think we’ve been through enough without hot-heads destroying everything we’ve worked for?” He wound down the window to let in the cold air, breathing deeply as if he felt faint. “Who are you anyway? What do you think you can do?”

“I’m a man,” Pavlov said, “who thinks there is more to be done than writing letters to the Prime Minister of England, the President of the United States and Mrs. Golda Meir.”

“What can you do?”

The Volga swerved violently to avoid a taxi with a drunken driver.

“I can show the world,” Pavlov said, “that we have balls.”

* * *

They met mostly in the open air, on the Lenin Hills, or in the birch forests to the west of the city where Muscovites went swimming from the river-beaches in the summer and cross-country ski-ing in the long winter.

Sometimes they met in a small apartment near the junction of Sadovaya Samotetchnaya and Petrovka. While they talked about Moscow Dynamo football team, mistresses and money they systematically searched the room for microphones. De-lousing it, they called the process. So far no bugs had been found.

They only met three at a time to avoid arousing suspicion. On this evening there was Pavlov, Yury Mitin, poet and State prize winner, and Ivan Shiller, a journalist on Pravda specialising in Jewish affairs. Each had cultivated an anti-Zionist front; none had Jew on his passport.

Each was fierce in his belief, none more so than Shiller, his anger fomented by the daily betrayals he had to perpetrate in his newspaper. Yesterday he had finished rounding up fifty prominent Jews and ordering them to sign a letter condemning Israeli aggression in the Middle East.

The letter also referred to emigration. “We were born and bred in the Soviet Union. It is here that our ancestors of many centuries lived and died. There is no reason why we should go to Israel. And, anyway, how is it possible to ‘return’ to a place where one has never been?”

“And do you know” – Shiller spoke with bitter contempt – “that some of them were quite happy to sign?”

Shiller was second-in-command of the Zealots who took their name from the 960 Jewish martyrs who killed themselves rather than surrender the citadel of Masada to the Romans. Death before dishonour. The Masada Complex symbolised the spirit of Israel: it symbolised the spirit of Russia’s small band of Zealots.

To avoid detection they used code-names each having a trade beginning with the letter P in the English language. Pavlov was the Professional, Mitin the Poet, Shiller the Penman.

Shiller was a gaunt man with a muddy complexion, hollow cheeks and bad teeth. His repressions were even stronger than Pavlov’s because, unlike Pavlov, he was a practising Jew. His greatest temptations came at such times as the New Year and the Atonement or the days when Yizkor, the prayer for the dead, was offered. Then he wanted to visit the Synagogue; but if he did he would alert the police. Even to be near the synagogue on Arkhipova on the Sabbath was dangerous because it was under K.G.B. surveillance. So Shiller prayed in private, ate his matzos in secret, recited the Passover prayer “Next year in Jerusalem”, and waited.

In one way Shiller was weaker than Pavlov: he was too religious to be a ruthless killer: Pavlov had no such inhibitions. But if there was ever to be any rift, any struggle for power, it would be between these two men.

The apartment belonged to Mitin the poet. He made coffee while, on a rickety table covered with linoleum, under the benign gaze of Lenin framed on the wall, the other two men played chess. A get-together of old friends should the 1 a.m. knock on the door be heard.

Shiller said bitterly: “Last week I helped to arrange the publication of a statement from our religious leaders. “Like citizens of other nationalities, Jews enjoy all the rights guaranteed by the Constitution, including the right to profess their own religion.”

He knocked aside one of Pavlov’s pawns with his bishop. “I got six so-called Rabbis’ signatures on that statement.”

“Shit on the Rabbi,” said the poet. He was a slim young man with a pale face, a monkish fringe of hair and a foul mouth. Whereas Shiller would have liked to smuggle Bibles into Russia, Mikin would have liked to smuggle Soviet literature out. His frustration found a small outlet in profanity, the brutalising of his love-affair with words.

Pavlov said: “We mustn’t get impatient. We’re all making sacrifices. We are getting nearer our goal every day.” He moved one of his own black bishops and called: “Check.”

“What goal?” Shiller asked. He frowned at the wooden board and pieces made in a labour camp. “Since when have we had a goal?”

“Piss on you,” exclaimed the poet. “We’ve had an ideal for years, a goal for months.”

“Ah,” Shiller muttered, “that goal. I apologise. I thought for a moment Pavlov meant we had a way of achieving it.”

Shiller moved his knight and Pavlov said: “You’re in check. Perhaps you misheard that as well.”

Shiller took back the knight without apologising. “How are we getting nearer our goal?”

Pavlov took a sheet of paper from his pocket. It had eleven names on it. Pavlov read out the first name, adding the data from memory.

“Skolsky.” He paused, thinking. Yosef Skolsky, aged forty-two. Top physicist at the Scientific Institute of Nuclear Physics, Moscow. A pupil of Academician Andrei Sakharov, the father of the Soviet atom bomb, our leading dissident. Two applications for exit visas to Israel. Refused on the grounds that his relatives in Tel Aviv were too distant.”

He read out another name. “Kremer, Yakov. Corresponding member of the U.S.S.R. Academy of Sciences. Aged fifty. One application refused. Again – remoteness of kin.”

The penultimate name was: “Zivz, Mikhail. Aged twenty-eight. Brilliant nuclear physicist working at the Scientific Research Centre in Akademgorodok fifteen miles from Novosibirsk. Permission refused once. Reason – still subject to Army service.”

The last name was Gopnik.

Shiller asked: “Who’s he?”

Pavlov swooped with his queen. “Checkmate,” he said.

“Who is Gopnik?”

“My conscience.”

Mitin served the coffee. “Since when did you have a conscience?” he asked.

Pavlov sipped the sweet black coffee. “It doesn’t matter.” He ran his hand through his hair. “What matters is this: ten of those eleven names constitute the human components of one hydrogen bomb. Quite a gift for the Promised Land, eh?”

* * *

But how? Part of the answer came to Viktor Pavlov at the Leningrad skyjack trial. This skyjack had failed miserably, but even if it succeeded, it would only have benefited a handful of nonentities. And, in any case, skyjacks were old-hat, bearing the hallmark of Arabs, Cubans and maniacs. An old-fashioned kidnap had more panache.

Once again the adrenalin started to flow. What if they kidnapped a Kremlin leader and held him against the release of the ten nuclear-physicists? The idea had a beautiful suicidal glory to it, the Masada Complex. Except that it was totally impracticable.

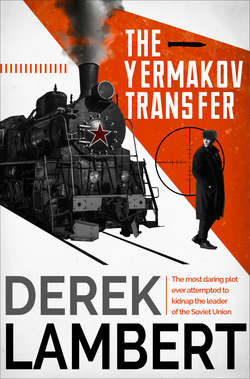

Or so it seemed until Viktor Pavlov heard that Vasily Yermakov was travelling on the Trans-Siberian Railway in the October of 1973, the year of the 25th anniversary of the founding of the State of Israel.