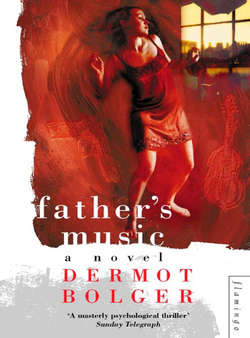

Читать книгу Father’s Music - Dermot Bolger - Страница 12

SIX

ОглавлениеTHE BEST WAY TO HIDE something, according to Luke, was to lay yourself so open that people forgot there was anything to hide. Enter any bar in overalls at closing time and you could walk off with the television, the slot machine or the very seats people sat on. The one place where people never saw things happen was under their noses.

That’s why I was wrong at fourteen to hide those initial cuts on my arms. Nobody might have noticed or I could have passed them off as an accident at school. If they hadn’t congealed into a secret, the habit might have lapsed and I would never have grown addicted to the sense of control it gave.

Control was something I’d never known in that house. Even Grandad Pete acquiesced to Gran without comment. Only my mother argued and, even then, half-heartedly, knowing she would be brow-beaten. Nothing could deflect Gran from her second chance to rear a success. At sixteen I was to pass my GCSEs and get into Saint David’s, the best sixth-form in Harrow. National Savings Certs were waiting to be cashed two years after that, when I would enter university, with every penny calculated so that nothing might distract me from my studies there. When Gran asked would I like to study science it wasn’t a question. I had the brains and it was where I might meet a successful prospective husband.

When mother argued that my teachers at Hillside High said I had a gift for English, Gran scoffed at the notion of an Arts degree. That was a catch-all for unambitious people with fuzzy brains and, besides, what would my mother know, having barely scraped through North London Poly before getting herself pregnant. It was a barb used to end all arguments. Mother retreated into silence like a beaten dog and I bent over my homework as if French verbs and equations were a precise world I could lose myself within.

I sometimes wondered about what life my mother might have led if I hadn’t been born, although, even then, I understood that it would never have been a stable one. She was too insecure, rearranging the most simple things until they fell apart in her hands. My father would probably have abandoned her anyway, but without the burden of me, she might have found a niche with someone decent who would lend her confidence. She had become attached to fellow patients in hospital, but whenever she was discharged Gran severed the contact, claiming my mother’s manic depression couldn’t be cured if she was perpetually reminded of it.

Occasionally I saw flushes of devil-may-care mischief in her: out shopping she might drag me into the pictures when we were due home. She’d take my hand and I’d glance at her face, wondering at what life might be like if she could break free of Gran. Only twice had she tried to do so: hitch-hiking around Ireland the summer before I was born and then plotting that disastrous holiday when I was eleven, during which she was blamed for losing me. I never talked about what happened on that trip and they learned not to question me, but for years those memories were still raw, if dormant, for us all.

Even without such tension, fourteen would never have been an easy age. It was a time of half-knowing everything, of self-consciousness, self-questioning and self-hatred. I nicknamed myself Burst Rubber, thrilling in its obscenity. I couldn’t stop visualising my own conception, from blue videos seen in friends’ houses and the magazines Joan Pitman’s brother had, which we found and shrieked with laughter at. There were no faces in the images in my mind, just two torsos – one white-bellied, the other shrouded with greying hair – and the sweating threadbare leather of a car in some Irish bog. The image kept recurring, even in school, a stumpy unwashed penis jutting in and out as the rubber snaps and gathers at the base among ancient curls. Still they rut on, oblivious to my fate passing between them, a fugitive seed meant to have been flung into a ditch, a tadpole struggling upstream to blight that white-bellied Englishwoman’s life.

I knew this was a self-loathing fantasy. Frank Sweeney had married my mother in Dublin, so presumably they once imagined some sort of life together. He had even briefly stayed in Harrow. But there was a collective amnesia about any mention of him.

That year I smoked every day after school with the girls in Cunningham Park as we eyed the lads who passed from the swings. Four of us drank a stolen bottle of vodka and myself and a girl called Clare Ashworth vomited into somebody’s garden on Devonshire Road. We drank cider in Headstone Cemetery with rough boys from Burnt Oak and Clare and I competed to see who could snog with them the longest in public. We dared each other to steal things we didn’t want from shops across from Harrow-on-the-Hill station. We skipped school to party, with curtains drawn and a red bulb in Clare’s living room when her parents were at work. Once we ran off in our skimpiest clothes to keep a vigil on a frozen night outside the recording studio where our favourite band was incorrectly rumoured to be and Clare took me home when I became hysterical for no apparent reason as we camped down in the graffiti-covered wall laneway.

One Saturday we had our noses pierced against our parents’ consent. On the train home we loudly pretended that our clitoris had been pierced, to embarrass the blushing geek who sat with his legs crossed in the next seat. After he left, we wondered more quietly if it really caused climaxes to last an extra twenty seconds, like Joan Pitman’s big sister said, or was she just a cow making it up. Afterwards I walked home with Clare. With the others gone we could stop pretending we weren’t scared. I kept a bandage over my nose all evening until Gran grew suspicious. When she pulled it off I broke down in tears.

Outside of home there was no public rebellion I couldn’t shame her with, but once inside the front door I was shrunk into being a child again as Gran railed against me wanting to rip my jeans or have my hair cropped. She controlled my appearance as carefully as every other aspect of my life. I was afraid to ask about any secrets they kept from me, and ashamed, in turn, to tell them the secrets which I had buried inside me.

Gran’s shame about my origins was bred into me. I told friends I had no idea who my father was. If they pressed, I said that all my mother remembered was that he was strong, white and French – or at least the wine he’d plied her with had been. In truth, all I possessed was his name on my birth certificate and all I knew for certain was that my cauled head and first cries had splintered their unlikely marriage apart. Sweeney had been fifty-nine when he met my mother who was twenty-two. He had abandoned us like Gran always claimed he would, within months of coming to Harrow. Callous, ignorant and selfish, he had been a man who would sooner play music then wash himself. A man who walked away at the first hint of responsibility, leaving his tainted blood coursing through my veins like an infection to be constantly watched.

In my mind I become fourteen again on that sleepless night when the addiction began. I have lain awake for hours, listening to droning voices argue about me downstairs, until I hear my mother’s defeated tread and her door close. I feel I can smell cigarette smoke in her room, the first of the dozen butts to be crumpled like spent cartridges in her bedside ashtray by dawn in her one act of defiance. Soon Gran will come up and check for the reassuring flash of the smoke alarm on the landing.

I am marooned by insomnia, almost physically feeling my body curve into new, unwanted shapes. Everything feels strange, except the sense of being a pawn between them. The house settles down with each of us awake, reliving the latest fight over my behaviour. They cannot understand this change. For years my reports were excellent, the perfect bright pupil, frighteningly articulate when not quiet as a doll in class. Now I know Gran is suggesting another school, still convinced that my behaviour is caused by bad influences. Nothing will be said but I’ll count the butts by my mother’s bedside and know that Gran won.

The radiator contracts with a sullen metallic groan. I am terrified the curtains are not closed properly and I’ll wake to find the moon’s face prying in on me. I hate myself for such a stupid fear, but even thinking about the moon brings those memories back. I play the game where it happened to someone else, but that doesn’t work. I can remember too much, the slanting church roof, the stink of his flesh. I’m a cow for allowing these memories back. My nails dig into my palms. My skin crawls with pent-up tension. Tomorrow my period is due, an unwanted novelty that has worn thin. I turn over, pressing my head into the pillow. My scream is so loud in my mind that I think they will hear. I breathe in the suffocating darkness of the pillow and lift my hands above my head but when I bring them down it is not the roots of my hair they tug at. I know whose hair it is. I have stared at her curls in the photograph on the sitting room wall. That 1960s schoolgirl smiling under her blue beret, surrounded by classmates who’ve swapped hippy beads for overweight husbands in Northwood and Kensington.

I want to scream that I am not my mother, but I cannot feel any sense of myself. I lie like a crumpled puppet, choked by everyone’s need for a second chance. I have felt disembodied once before, after taking pills Clare had found. But the way my body rocks in the bed is more frightening. I twist my head, desperate for comfort, and screw my eyes shut. Other eyes, huge and unblinking, watch from the blurred after-image invading the darkness beyond my eyes: the eyes of the Man in the Moon. They change to those of a fly, triangular legs and twitching limbs tussled in a spider’s web. I’m going mad, like my mother. I want to cry for help like a child. But I am fourteen, with buds of breasts and the downiest of hair and the weight of expectations like a skin hardening over mine.

There is a shard of pain as some hair comes loose. I grimace and let go, my knuckles intertwining above my head, fingers clawing against fingers. A fragment of fingernail peels away. It just happens with a sharp incision of pain. I gasp. The nail hangs, jagged and half broken off. I press it across my wrist and squeeze my face into the pillow, too shocked to feel pain or cry out. What I feel is a flush of revenge. I am damaged goods if I could only tell them. Now I am soiling this replica schoolgirl they’ve tried to create. But suddenly it hurt and aches more as I keep scratching till my arm is a mass of scars.

Then, just as suddenly, it hurts less, as if an amphetamine was unleashed into my bloodstream. The sensation is of giddy exhilaration. If my body is theirs to move about, then these scars are my graffiti scrawled on it. It is no longer myself I’m hurting, but their possession. Without warning, the elixir fades and the brief, startling high is gone. Only a throbbing pain is left, another bewildering layer of guilt, and a fear of discovery which makes me dress next morning with the door locked. I don’t know what I have done or why. I’m frightened of what Gran will do if the scars are discovered. I cannot eat with worry. I clench my sleeve under the table before cycling off, waving with my undamaged hand like the dutiful schoolgirl they all long for.

Now I am twenty-two again and Luke is fucking me. It is the fourth of October, the first of those Sunday evenings we will spend in that hotel. The bedspread is ancient and frayed. It grates against my breasts as I press my face into the pillow. He grips my hips, raising them to meet his thrusts. I can’t understand why, since he started touching me, I keep vividly recalling being fourteen again. But the years in between keep disappearing. I feel I’m back in my childhood bedroom. I raise my hands above my head and seem about to stab at my neck before Luke grabs my wrists and pins them down. I am grateful he is withdrawn into his own silent world. I pull my hands free and intertwine the fingers, protecting my neck from him or myself. Luke is suddenly still, watching in the light from the window, with not even his cock moving inside me.

Perhaps he wants to prolong it, anxious not to come too soon. But I feel he can sense this malaise within me. He appears to wait for permission to continue. The pillow is wet. What a kip, I think, even with damp bedclothes. Then I realise I’m crying. I thrust my hips backwards, I want Luke to move, I want to break the spell of uninvited memories. Luke stirs and I try to focus on his hands or cock. But it’s like an outer layer of skin has been split open and I am shocked to find my younger self preserved within. I feel robbed of the person I’ve carefully become and stripped more naked than I ever wish to be again.

These blocked out memories have been swamping me ever since Luke pulled my sweater over my head while undressing me. It is something I have never let any man do before. It reeked too much of being somebody’s plaything and was too intimate to be allowed, just like I never permitted some men to kiss my lips. But tonight with Luke it seemed less an act of possession than of boyish wonder.

Tonight he seems less sure of himself, as if surprised at my arrival. There has been bad news, he says, but it doesn’t involve him. We are like strangers with little to say, initially as awkward as adolescents. The pretence remains that we are purely here for sex, even if we each suspect there is more to it than that, but are uncertain of what it may be.

There is no sense that we have ever made love before as Luke undresses me. The room is freezing, but he takes his time, starting with my shoes and slowly removing my jeans. I raise my hips, lying back to help and then lean forward, returning his silent smile as I lift my arms to allow him to pull my woollen sweater up. For a second it covers my eyes and, unbidden, the first memory comes. My breath grows faster. I cannot even scream. Luke stops, with the sweater half over my head, disturbed by this sudden tensing of my body.

‘What’s wrong?’ he says.

‘Pull the bloody jumper off!’

He does so and I shake my hair free, lying back on the eiderdown with my eyes tightly shut. Luke pauses, unsure of what is happening. Then he begins unbuttoning my blouse. I feel his fingers but am only half aware of them. The memories are so vivid that if I open my eyes I feel I will be back in Gran’s kitchen.

I feel my school polo-neck being yanked over my face again so that I’m momentarily blinded. I think I’m suffocating as Mammy holds me down and Gran draws my scarred arms from the sleeves. The kitchen blinds are closed against prying eyes. My flesh is goosepimpled. I feel violated, struggling to extract my head from the polo-neck as Gran fingers the scars. I jerk free from my mother and half fall with the polo-neck caught around my throat. I can’t breathe, I’m going to choke. Mammy senses my panic and panics herself, tugging at the twisted garment as Gran shouts at her to pull it off. It comes free and I close my eyes against the questions they keep repeating.

Did a boy inflict these scars? Why had I kept them hidden? Had a man done anything, a neighbour or a teacher who’d warned me against speaking? Was I in trouble? I sense Gran’s fear in this euphemism, her terror of a cycle repeating. Neither of them understand what I need to tell them. I hate them for that as much as I hate myself. A new voice at my ear, a monkey with no face, whispers that I should punish them too.

For three weeks I’ve hidden these bruised arms away, skipping school to avoid swimming and locking the bathroom when I washed. At night I’ve only half slept, promising myself I would leave my arms untouched, even counting the hours I managed to stay this itch. But always I know that at some stage the scratching and biting will begin again. Nothing prevents it, silent pacing or meaningless prayers. Behind the radiator I keep a shattered plastic ruler. This ache only stops when I use it to draw blood and creep downstairs for watered whisky to ease the pain. A map of purple bruising stretches up to my shoulders. The addiction feeds on the fear of discovery. Twice I’ve dreamt my mother has found me in pain and taken me in her arms. Twice I’ve woken disappointed to fret about hiding the flecks of blood where my arm rested on the pillow.

But now, as they stare at my arms in the kitchen, I am suddenly defiant. They are scared of me for the first time in my life. I have stepped beyond their control. The discovery gives me strength. I sit with half my school uniform torn off. I know I cannot explain these scars but now I don’t want to. I hate Mammy for being weak and I’m ashamed of her illness. I hate Gran because I need someone to blame and because no matter how hard I try I can never achieve her dreams heaped on my shoulders.

Even as a baby they had forced me to choose, playing a game where they called from different sides of the playground to see who I’d run to. I remember tottering back and forth until I sat down crying with my arms over my head. Now I stare at their faces, then arch my fingers to scratch my neck with nails I have let grow jagged. I don’t notice whose hand grabs my arm. I call out with what sounds like a shriek of pain but is a cry of freedom.

My cry echoes in this hotel room. I open my eyes, surprised by the sound, like someone waking up. Luke has entered me. He stops, his scared eyes looking into mine.

‘What’s wrong?’ he says. ‘Have I hurt you?’

‘It’s nothing to do with you,’ I say. ‘I didn’t ask you to stop.’

‘Are you okay?’

‘Last week you said you just wanted a fuck,’ I tell him. ‘This is private. My life is none of your concern.’

I close my eyes, feeling Luke hesitate, then enter me, deep and deeper. Once these memories start they will not stop. I even know the sequence they will follow: the rows as Gran forcibly cut my nails, the dark games where the closer they examined my body the more secretively I hid my scars. Then the doctors and specialists, hours of queueing for professional voices to probe why I was asking for help. The ink dots and idiotic tests, folders crammed with pictures of the moon which I sullenly drew in their offices. And the suspicion that fell about our house, the rumours I could set into motion, making my grandparents live in fear until I controlled their lives for the next three years. Yet, even at the summit of that power, I still lacked courage to speak about the man in the moon and nothing could touch the core of pain within me.

That pain should be banished, now because I am twenty-two, a new person with a new life. I open my eyes. I’m in a hotel bedroom, being fucked – like my mother at that age – by an Irishman. I don’t know why the memories have returned, or why my mother seems close, as if watching now. But when I close my eyes an adolescent image returns: dark bogland and sweating leather, grey hairs around a penis jutting out and in. I stretch my arms out, wanting to be held. Can they not see what’s happening before their eyes? Can they not even try to understand?

But Luke doesn’t understand. I feel him withdraw and his arms turn me over. The bedspread is ancient and frayed. It grates against my breasts. He grips my hips, raising them to meet his thrusts. I press my face into the pillow and the ache is as insatiable as it always was, and the gulf between me and the world is like a scar that can be hidden but never healed.